مستقبل مستضد كيميري

مستقبلات المستضد الكيميري Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs)، (وتعرف أيضاً بالمستقبلات المناعية الكيميرية chimeric immunoreceptors، مستقبلات الخلايا التائية الكيميرية chimeric T cell receptors، مستقبلات الخلايا التائية الاصطناعية artificial T cell receptors أو CAR-T)، هي مستقبلات معدلة وراثياً والتي تُطعم خاصية معينة في الخلية المستجيبة للمناعة (الخلية التائية). عادة، تستخدم هذه المستقبلات لتطعيم خاصية الضد وحيد النسيلة داخل خلية تائية، مع تيسير تسلسل الترميز الخاص بها عن طريق النواقل الڤيروسية. يطلق على هذه المستقبلات اسم الكيميرات لأنها تتكون من أجزاء من مصادر مختلفة.

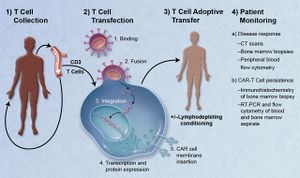

علاج المستقبل المستضد الكميري للسرطان، يستخدم تقنية تسمى نقل الخلية المقتبس،[1] والذي حاز موافقة ادارة الغذاء والدواء الأمريكية كي يستخدم لعلاج سرطان الدم الليمفاوي الحاد.[2] يتم إزالة الخلايا التائية من المريض وتعديلها كي تتمكن من التعبير عن مستقبلات محددة لنوع السرطان الخاص بالمريض. الخلايا التائية، والتي يمكنها بعد ذلك التعرف على الخلايا السرطانية والقضاء عليها، يتم إعادة إدخالها لجسم المريض. تعديل الخلايا التائية المستمدة من المتبرعين بدلاً من المريض هي أيضاً تحت الدراسة.

المبدأ الأساسي لتصميم الخلايا التائية لمستقبلات المستضد الكيميري يتضمن مستقبلات مؤشبة تجمع وظائف لربط المستضد ولتفعيل الخلية التائية. المقدمة العامة للخلايا التائية لمستقبلات المستضد الكيميري هي التوليد السريع للخلايا التائية التي تستهدف خلايا أورام معينة. وبإمكان العلماء أن يزيلوا الخلايا التائية من مريض، ثم يهندسونها وراثياً، ثم يعيدونها إلى المريض لكي تعمل ضد الخلايا السرطانية.[3] وبمجرد اتمام هندسة الخلية التائية لتصبح خلية تائية مستقبلة لمستضد كيميري CAR T-Cell، فإنها تحصل على خصائص فوق فسيولوجية وتطوِّر القدرة على العمل كـ ‘عقار حي’.[4] الخلايا التائية المستقبلة لمستضد كيميري تخلق رابط بين نطاق تعرف على ربيطة خارج الخلية وبين جزيء إشارة داخل الخلية، الذي بدوره ينشّط الخلايا التائية. نطاق التعرف على الربيطات خارج الخلية عادةً ما يكون قِسم متغير أحادي السلسلة (scFv). السؤال الذي كثيراً ما يُطرح حول سلامة هذا العلاج هو كيف يمكن التأكد أن خلايا الورم السرطاني فقط هي التي سوف تُستهدف وليس الخلايا العفية الطبيعية؟ التخصص والسلام للخلايا التائية المستقبلة للمستضد الكيميري يحددها اختيار الجزيء المستهدَف.[5]

الخلية التائية لمستقبلات المستضد الكيميري (خ.ت.م.م.ك CAR-T) يمكن اشتقاقها إما من دم المريض نفسه (اغتراس ذاتي) أو تُشتق من متبرع آخر عفي (زرع الطعم الخيفي). تلك الخلايا التائية مُهندَسة وراثياً لإظهار مستقبل خلية تائية اصطناعي، الذي من خلاله يجري استهدام المستضدات المتعلقة بالمرض.[6] هذه العملية هي مستقلة عن MHC ولذلك فإن كفاءة الاستهداف تزداد جداً. هذه الخلايا التائية المستقبلة للمستضدات الكيميرية تكون مبرمجة لاستهدام المستضدات التي تكون متواجدة على أسطح الأورام. وحين يتصلون بالمستضدات على الأورام، فإن الخلايا التائية لمستقبلات المستضد الكيميري تتنشط عبر پپتيد الإشارة، وتنتشر وتصبح سامة للخلية. ويقومون بكل ذلك بشكل مستقل عن معقد توافق الأنسجة الرئيسي (MHC)[7] الخلايا التائية لمستقبلات المستضد الكيميري تدمر خلايا السرطان عبر آليات مثل الانتشار المستحث بشدة للخلايا، مما يزيد من درجة التي تصبح عندها الخلية سامة للخلايا الحية الأخرى، أي سمية الخلايا، وبالبتسبب في زيادة انتاج العوامل المُفرزة من الخلايا في جهاز المناعة التي لها مفعول على الخلايا الأخرى في العضية. تلك العوامل تُسمى سيتوكينات وتضم إنترلوكنات و إنترفيرونات وعوامل نمو.[8]

الحالة المرغوبة التي تعمل فيها مستقبل مستضد كيميري لخلية تائية هي أنهم سيكونوا محددين لمستضد ظاهر في ورم وليس بظاهر في أي خلية عفية في الجسد تعمل بشكل طبيعي. CD19 يظهر (أو يُعبَّر عن) على الخلايا البائية طوال تطورهم وكنتيجة لذلك، كما تظهر CD19 على تقريباً كل الأورام الخبيثة للخلايا البائية. بالاضافة لذلك، فإن CD19 يظهر فقط في نسب الخلية البائية وليس في أي نسب أو أنسجة أخرى. تلك الأورام الخبيثة تضم أشكالاً من السرطان مثل لوكيميا الأرومة اللمفاوية الحادة (ALL)، اللوكيميا الليمفاوية المزمنة (CLL)، والعديد من الأشكال المختلفة للمفومة هودجكن.[9]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الاستخدام في السرطان

النقل لتبني الخلايا التائية التي تُظهـِر مستقبلات للمستضدات الكيميرية هو علاج واعد للسرطان، إذ يمكن هندسة الخلايا التائية المستقبلة للمستضدات الكيميرية لإستهداف تقريباً أي مستضد مقترن بورم. ويوجد إمكانيات هائلة لهذه المقاربة لتحسين علاج السرطان لكل شخص حسب جيناته وجينات مرضه، بشكل مختلف تماماً عن كل العلاجات السابقة. فبعد جمع الخلايا التائية من المريض، فإن الخلايات تُهندَس وراثياً لإظهار مستقبلات للمستضدات الكيميرية CAR الموجهة تحديداً لإستهداف المستضدات المتواجدة على خلايا الأورام في هذا المريض تحديداً، ثم تـُحقن في المريض.[10]

موافقات FDA المبكرة

أول علاجين وافقت عليهم FDA يستخدمان الخلايا التائية لمستقبلات المستضدات الكيميرية يستهدفان CD19 (الموجود في أنواع عديدة من خلايا اللمفوما).[11] وقد حصلا على موافقة لمعالجة لمفوما الخلية البائية الكبيرة المنتشرة المنتكسة/المنيعة (DLBCL) لكل من أكسيكابتاجين سايلوليوسل وسابق الخلية البائية المنتكسة/المنيعة لوكيميا الأرومة اللمفاوية الحادة (ALL) لـ تيساجنلكلوسل.[11]

التركيب

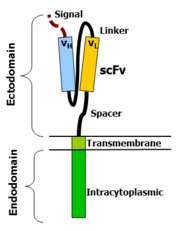

تتكون مستقبلات المستضدات الكيميرية من ثلاث مناطق: نطاق خارجي و نطاق عبر الغشاء و نطاق داخلي.

النطاق الخارجي

The ectodomain is the region of the receptor that is exposed to the extracellular fluid and consists of 3 components: a signalling peptide, an antigen recognition region and a spacer.

A signal peptide directs the nascent protein into the endoplasmic reticulum. The signal protein in CAR is called a single-chain variable fragment (scFv),[12] a type of protein known as a fusion protein or chimeric protein. A fusion protein is a protein that is formed by merging two or more genes that code originally for different proteins but when they are translated in the cell, the translation produces one or more polypeptides with functional properties derived for each of the original genes.[13]

A scFv is a chimeric protein made up of the light and heavy chains of immunoglobins connected with a short linker peptide. The linker consists of hydrophilic residues with stretches of glycine and serine in it for flexibility as well as stretches of glutamate and lysine for added solubility.[14]

النطاق عبر الغشاء

The transmembrane domain is a hydrophobic alpha helix that spans the membrane. The transmembrane domain is essential for the stability of the receptor as a whole. At present, the CD28 transmembrane domain is the most stable of the domains.

Generally, the transmembrane domain from the most membrane proximal component of the endodomain is used. Interestingly, using the CD3-zeta transmembrane domain may result in incorporation of the artificial TCR into the native TCR, a factor that is dependent on the presence of the native CD3-zeta transmembrane charged aspartic acid residue.[15] Different transmembrane domains result in different receptor stability. The CD28 transmembrane domain results in a highly expressed, stable receptor.

النطاق الداخلي

This is the functional end of the receptor. After antigen recognition, receptors cluster and a signal is transmitted to the cell.[12] The most commonly used endodomain component is CD3-zeta which contains 3 ITAMs. This transmits an activation signal to the T cell after the antigen is bound. CD3-zeta may not provide a fully competent activation signal and co-stimulatory signaling is needed. For example, chimeric CD28 and OX40 can be used with CD3-Zeta to transmit a proliferative/survival signal or all three can be used together.

تطور تصميم الخلايا التائية لمستقبل المستضاد الكيميري

First generation CARs were developed in 1989 by Gideon Gross and Zelig Eshhar[17][18] at Weizmann Institute, Israel.[19] The first generation of CARs are composed of an extracellular binding domain, a hinge region, a transmembrane domain, and one or more intracellular signaling domains.[6] Extracellular binding domain contains single‐chain variable fragments (scFvs) derived from tumor antigen‐reactive antibodies and usually have high specificity to tumor antigen.[6] All CARs harbor the CD3ζ chain domain as the intracellular signaling domain, which is the primary transmitter of signals. Second generation CARs also contain co‐stimulatory domains, like CD28 and/or 4‐1BB. The involvement of these intracellular signaling domains improve T cell proliferation, cytokine secretion, resistance to apoptosis, and in vivo persistence.[6] Besides co-stimulatory domains, the third‐generation CARs combine multiple signaling domains, such as CD3z-CD28-41BB or CD3z-CD28-OX40, to augment T cell activity. Preclinical data shows the third-generation CARs exhibit improved effector functions and in vivo persistence as compared to second‐generation CARs.[6] Recently, the fourth‐generation CARs (also known as TRUCKs or armored CARs), combine the expression of a second‐generation CAR with factors that enhance anti‐tumoral activity (e.g., cytokines, co‐stimulatory ligands).[20]

The evolution of CAR therapy is an excellent example of the application of basic research to the clinic. The PI3K binding site used was identified in co-receptor CD28,[21] while the ITAM motifs were identified as a target of the CD4- and CD8-p56lck complexes.[22]

The introduction of Strep-tag II sequence (an eight-residue minimal peptide sequence (Trp-Ser-His-Pro-Gln-Phe-Glu-Lys) that exhibits intrinsic affinity toward streptavidin[23]) into specific sites in synthetic CARs or natural T-cell receptors provides engineered T cells with an identification marker for rapid purification, a method for tailoring spacer length of chimeric receptors for optimal function and a functional element for selective antibody-coated, microbead-driven, large-scale expansion.[24][25] Strep-tag can be used to stimulate the engineered cells, causing them to grow rapidly. Using an antibody that binds the Strep-tag, the engineered cells can be expanded by 200-fold. Unlike existing methods this technology stimulates only cancer-specific T cells.[بحاجة لمصدر]

الخلية التائية الذكية

Combined with exogenous molecules, some synthetic control devices have been implemented on CAR-T cells and alter the cell activity. Smart T cell is engineered with suicide gene or other synthetic control panels to precisely control therapeutic function over the timing and dosage, there by alleviating cytotoxicity.[26] Several strategies to improve safety and efficacy of CAR-T cells are:

هندسة جين الانتحار: engineered T cells are incorporated with suicide genes, which can be activated by extracellular molecule and then induce T cell apoptosis. Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) and inducible caspase 9 (iCas9) are two types suicide genes have been integrated into CAR-T cells.[26][27][28] In iCas9 system, the suicide gene is composed of the sequence of the mutated FK506-binding protein with high specificity to a small-molecule, AP1903 and a gene encoding human caspase 9 switch. When the release of cytokines by CAR-T cells becomes more pronounced than basic levels, the iCas9 can be dimerized and lead to rapid apoptosis of T cells. Although both suicide genes demonstrate a noticeable function of as a safety switch in clinical trials for cellular therapies, some hinder defects limit the application of this strategy. HSV-TK is derived from virus and may be immunogenic to humans.[26][29] The suicide gene strategies may not act quickly enough to eliminate off-tumor cytotoxicity as well.

مستقبل المستضدَين: T cells are engineered to express two tumor-associated antigen receptors at the same time. The dual-antigen receptor of engineered T cell module has been reported to have less intense side effects.[30] The activation of CAR-T cell via TCR-CD3ζ signal transduction pathway is transient and a complementary signal pathway provided by co-stimulatory molecules on antigen presenting cells promotes survival of modified-T cell can ability in controlling tumor.[31] An in vivo study in mice shows the dual-receptor T cells effectively eradicated prostate cancer and achieved complete long-term survival.[32]

مفتاح التشغيل: ON-switch CAR-T cell split synthetic receptors into two parts: the first part mainly contains an antigen binding domain towards and the other part features two different downstream signaling elements (e.g. CD3ζ and 4-1BB). Upon the presence of an exogenous molecule (rapamycin analogs for example), two physically separated signaling elements fuse together and CAR-T cells exert therapeutic functions.[33] In this mechanism, the engineered T cell shows therapeutic function only in the presence of both tumor antigen and a benign exogenous molecule.

الجزيئات ثنائية الوظائف كمفاتيح: The bispecific antibodies are developed as an efficacious bridge to target cytotoxic T cells to cancer cells and causes localized T cell activation. In this strategy, the bispecific antibody targets CD3 molecule of T cell and tumor-associated antigen presented on cancer cell surface.[34] The anti-CD20/CD3 bispecific molecule shows high specificity to both malignant B cells and cancer cells in mice.[35] FITC is another bifunctional molecule used in this strategy. FITC can redirect and regulate the activity of the FITC-specific CAR-T cells toward tumor cells with folate receptors.[36]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

تقنية محول وحدات الدواء الجزيئية الصغيرة

SMDCs (small molecule drug conjugates) platform in immuno-oncology is a novel (currently experimental) approach that makes possible the engineering of a single universal CAR T cell, which binds with extraordinarily high affinity to a benign molecule designated as FITC. These cells are then used to treat various cancer types when co-administered with bispecific SMDC adaptor molecules. These unique bispecific adaptors are constructed with a FITC molecule and a tumor-homing molecule to precisely bridge the universal CAR T cell with the cancer cells, which causes localized T cell activation. Anti-tumor activity in mice is induced only when both the universal CAR T cells plus the correct antigen-specific adaptor molecules are present. Anti-tumor activity and toxicity can be controlled by adjusting the administered adaptor molecule dosing. Treatment of antigenically heterogeneous tumors can be achieved by administration of a mixture of the desired antigen-specific adaptors. Thus, several challenges of current CAR T cell therapies, such as:

- the inability to control the rate of cytokine release and tumor lysis

- the absence of an “off switch” that can terminate cytotoxic activity when tumor eradication is complete

- a requirement to generate a different CAR T cell for each unique tumor antigen

may be solved or mitigated using this approach.[37][38][39]

دراسات سريرية

أمثلة مبكرة

| المستضد المستهدف | الخباثة المرتبطة | نوع المستقبل | جيل م.م.ك |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Folate receptor | سرطان المبيض | ScFv-FcεRIγCAIX | الأول |

| CAIX | سرطان الخلايا الكلوية | ScFv-FcεRIγ | الأول |

| CAIX | سرطان الخلايا الكلوية | ScFv-FcεRIγ | الثاني |

| CD19 | الخلايا الخبيثة في الخلايا البائية | ScFv-CD3ζ (EBV) | الأول |

| CD19 | الخلايا الخبيثة في الخلايا البائية، CLL | ScFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| CD19 | B-ALL | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CD19 | ALL | CD3ζ(EBV) | الأول |

| CD19 | ALL post-HSCT | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CD19 | سرطان الدم، سرطان الغدد اللميفاوية، CLL | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ vs. CD3ζ | الأول والثاني |

| CD19 | B-cell malignancies | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CD19 | B-cell malignancies post-HSCT | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CD19 | Refractory Follicular Lymphoma | ScFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| CD19 | B-NHL | ScFv -CD3ζ | الأول |

| CD19 | B-lineage lymphoid malignancies post-UCBT | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CD19 | CLL, B-NHL | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CD19 | B-cell malignancies, CLL, B-NHL | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CD19 | ALL, lymphoma | ScFv-41BB-CD3ζ vs CD3ζ | الأول والثاني |

| CD19 | ALL | ScFv-41BB-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CD19 | الخلايا الخبيثة في الخلايا البائية | ScFv-CD3ζ (Influenza MP-1) | الأول |

| CD19 | الخلايا الخبيثة في الخلايا البائية | ScFv-CD3ζ (VZV) | الثاني |

| CD20 | اللميفومات | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CD20 | الخلايا الخبيثة في الخلايا البائية | ScFv-CD4-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CD20 | الخلايا الخبيثة في الخلايا البائية | ScFv-CD3ζ | First |

| CD20 | Mantle cell lymphoma | ScFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| CD20 | Mantle cell lymphoma, indolent B-NHL | CD3 ζ /CD137/CD28 | الثالث |

| CD20 | indolent B cell lymphomas | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | Second |

| CD20 | Indolent B cell lymphomas | ScFv-CD28-41BB-CD3ζ | الثالث |

| CD22 | الخلايا الخبيثة في الخلايا البائية | ScFV-CD4-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CD30 | الليمفومات | ScFv-FcεRIγ | الأول |

| CD30 | ليمفومة هيدجين | ScFv-CD3ζ (EBV) | الأول |

| CD33 | AML | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CD33 | AML | ScFv-41BB-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CD44v7/8 | Cervical carcinoma | ScFv-CD8-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CEA | سرطان الثدي | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| CEA | سرطان القولون | ScFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| CEA | سرطان القولون | ScFv-FceRIγ | الأول |

| CEA | سرطان القولون | ScFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| CEA | سرطان القولون | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | Second |

| CEA | سرطان القولون | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | Second |

| EGP-2 | خلايا خبيثة متعددة | scFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| EGP-2 | خلايا خبيثة متعددة | scFv-FcεRIγ | الأول |

| EGP-40 | سرطان القولون | scFv-FcεRIγ | الأول |

| erb-B2 | سرطان القولون | CD28/4-1BB-CD3ζ | الثالث |

| erb-B2 | سرطان الثدي وسرطانات أخرى | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| erb-B2 | سرطان الثدي وسرطانات أخرى | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ (Influenza) | الثاني |

| erb-B2 | سرطان الثدي وسرطانات أخرى | ScFv-CD28mut-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| erb-B2 | سرطان البروستاتات | ScFv-FcεRIγ | الأول |

| erb-B 2,3,4 | سرطان الثدي وسرطانات أخرى | Heregulin-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| erb-B 2,3,4 | سرطان الثدي وسرطانات أخرى | ScFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| FBP | سرطان المبيضين | ScFv-FcεRIγ | الأول |

| FBP | سرطان المبيضين | ScFv-FcεRIγ (alloantigen) | الأول |

| Fetal acetylcholine receptor | Rhabdomyosarcoma | ScFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| GD2 | Neuroblastoma | ScFv-CD28 | الأول |

| GD2 | Neuroblastoma | ScFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| GD2 | Neuroblastoma | ScFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| GD2 | Neuroblastoma | ScFv-CD28-OX40-CD3ζ | الثالث |

| GD2 | Neuroblastoma | ScFv-CD3ζ (VZV) | الأول |

| GD3 | Melanoma | ScFv-CD3ξ | الأول |

| GD3 | Melanoma | ScFv-CD3ξ | الأول |

| Her2/neu | Medulloblastoma | ScFv-CD3ξ | الأول |

| Her2/neu | أورام الرئة الخبيثة | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| Her2/neu | Advanced osteosarcoma | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| Her2/neu | Glioblastoma | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| IL-13R-a2 | Glioma | IL-13-CD28-4-1BB-CD3ζ | الثالث |

| IL-13R-a2 | Glioblastoma | IL-13-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| IL-13R-a2 | Medulloblastoma | IL-13-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| KDR | Tumor neovasculature | ScFv-FcεRIγ | الأول |

| k-light chain | B-cell malignancies | ScFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| k-light chain | (B-NHL, CLL) | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ vs CD3ζ | الثاني |

| LeY | Carcinomas | ScFv-FcεRIγ | الأول |

| LeY | Epithelial derived tumors | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| L1 cell adhesion molecule | Neuroblastoma | ScFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| MAGE-A1 | Melanoma | ScFV-CD4-FcεRIγ | الثاني |

| MAGE-A1 | Melanoma | ScFV-CD28-FcεRIγ | الثاني |

| Mesothelin | أورام متعددة | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| Mesothelin | الثاني | ScFv-41BB-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| Mesothelin | الثاني | ScFv-CD28-41BB-CD3ζ | الثالث |

| Murine CMV infected cells | Murine CMV | Ly49H-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| MUC1 | الثدي والمبيضين | ScFV-CD28-OX40-CD3ζ | الثالث |

| NKG2D ligands | الثاني | NKG2D-CD3ζ | الأول |

| Oncofetal antigen (h5T4) | الثاني | ScFV-CD3ζ (vaccination) | الأول |

| PSCA | Prostate carcinoma | ScFv-b2c-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| PSMA | Prostate/tumor vasculature | ScFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| PSMA | Prostate/tumor vasculature | ScFv-CD28-CD3ζ | الثاني |

| PSMA | Prostate/tumor vasculature | ScFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| TAA targeted by mAb IgE | Various tumors | FceRI-CD28-CD3ζ (+ a-TAA IgE mAb) | الثالث |

| TAG-72 | Adenocarcinomas | scFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

| VEGF-R2 | Tumor neovasculature | scFv-CD3ζ | الأول |

النقل المقتبس لخلايا المستقبلات المستضدة الكيميرية المعدلة كعلاج للسرطان

الهندسة الوراثية للخلايا التائية لمستقبلات المستضد الكيميري

مخاوف السلامة

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

موافقات ادارة الغذاء والدواء المبكرة

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ Pule, M; Finney H; Lawson A (2003). "Artificial T-cell receptors". Cytotherapy. 5 (3): 211–26. doi:10.1080/14653240310001488. PMID 12850789.

- ^ Gallagher, James (30 August 2017). "Historic 'living drug' gets go-ahead". BBC. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Fox, Maggie (July 12, 2017). "New Gene Therapy for Cancer Offers Hope to Those With No Options Left". NBC News.

- ^ Sadelain M, Brentjens R, Rivière I (April 2013). "The basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design". Cancer Discovery. 3 (4): 388–98. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0548. PMC 3667586. PMID 23550147.

- ^ Srivastava S, Riddell SR (August 2015). "Engineering CAR-T cells: Design concepts". Trends in Immunology. 36 (8): 494–502. doi:10.1016/j.it.2015.06.004. PMC 4746114. PMID 26169254.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Hartmann J, Schüßler-Lenz M, Bondanza A, Buchholz CJ (2017). "Clinical development of CAR T cells-challenges and opportunities in translating innovative treatment concepts". EMBO Molecular Medicine. 9 (9): 1183–1197. doi:10.15252/emmm.201607485.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHartmann2017 - ^ Tang XJ, Sun XY, Huang KM, Zhang L, Yang ZS, Zou DD, Wang B, Warnock GL, Dai LJ, Luo J (December 2015). "Therapeutic potential of CAR-T cell-derived exosomes: a cell-free modality for targeted cancer therapy". Oncotarget. 6 (42): 44179–90. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.6175. PMC 4792550. PMID 26496034.

- ^ Maude SL, Teachey DT, Porter DL, Grupp SA (June 2015). "CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Blood. 125 (26): 4017–23. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-12-580068. PMC 4481592. PMID 25999455.

- ^ Jacobson CA, Ritz J (November 2011). "Time to put the CAR-T before the horse". Blood. 118 (18): 4761–2. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-09-376137. PMID 22053170.

- ^ أ ب Thumbs Up to Latest CAR T-Cell Approval - New era for lymphoma, leukemia, possibly other cancers. Oct 2017

- ^ أ ب Zhang C, Liu J, Zhong JF, Zhang X (2017-06-24). "Engineering CAR-T cells". Biomarker Research. 5: 22. doi:10.1186/s40364-017-0102-y. PMID 28652918.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Monnier, Philippe P.; Vigouroux, Robin J.; Tassew, Nardos G. (April 2013). "In Vivo Applications of Single Chain Fv (Variable Domain) (scFv) Fragments". Antibodies. 2 (2): 193–208. doi:10.3390/antib2020193.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Baldo BA (May 2015). "Chimeric fusion proteins used for therapy: indications, mechanisms, and safety". Drug Safety. 38 (5): 455–79. doi:10.1007/s40264-015-0285-9. PMID 25832756.

- ^ Bridgeman JS, Hawkins RE, Bagley S, Blaylock M, Holland M, Gilham DE (June 2010). "The optimal antigen response of chimeric antigen receptors harboring the CD3zeta transmembrane domain is dependent upon incorporation of the receptor into the endogenous TCR/CD3 complex". Journal of Immunology. 184 (12): 6938–49. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0901766. PMID 20483753.

- ^ Casucci, Monica; Attilio Bondanza (2011). "Suicide Gene Therapy to Increase the Safety of Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Redirected T Lymphocytes". Journal of Cancer. 2: 378–382. doi:10.7150/jca.2.378. PMC 3133962. PMID 21750689. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Gross G, Gorochov G, Waks T, Eshhar Z (February 1989). "Generation of effector T cells expressing chimeric T cell receptor with antibody type-specificity". Transplantation Proceedings. 21 (1 Pt 1): 127–30. PMID 2784887.

- ^ Rosenbaum L (October 2017). "Tragedy, Perseverance, and Chance - The Story of CAR-T Therapy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (14): 1313–1315. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1711886. PMID 28902570.

- ^ Gross G, Waks T, Eshhar Z (December 1989). "Expression of immunoglobulin-T-cell receptor chimeric molecules as functional receptors with antibody-type specificity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 86 (24): 10024–8. Bibcode:1989PNAS...8610024G. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.24.10024. JSTOR 34790. PMC 298636. PMID 2513569.

- ^ Chmielewski M, Abken H (2015). "TRUCKs: the fourth generation of CARs". Expert Opin Biol. 15 (8): 1145–1154. doi:10.1517/14712598.2015.1046430.

- ^ Rudd CE, Schneider H (July 2003). "Unifying concepts in CD28, ICOS and CTLA4 co-receptor signalling". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 3 (7): 544–56. doi:10.1038/nri1131. PMID 12876557.

- ^ Rudd CE (January 1999). "Adaptors and molecular scaffolds in immune cell signaling". Cell. 96 (1): 5–8. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80953-8. PMID 9989491.

- ^ Schmidt TG, Skerra A (2007). "The Strep-tag system for one-step purification and high-affinity detection or capturing of proteins". Nature Protocols. 2 (6): 1528–35. doi:10.1038/nprot.2007.209. PMID 17571060.

- ^ Liu L, Sommermeyer D, Cabanov A, Kosasih P, Hill T, Riddell SR (April 2016). "Inclusion of Strep-tag II in design of antigen receptors for T-cell immunotherapy". Nature Biotechnology. 34 (4): 430–4. doi:10.1038/nbt.3461. PMC 4940167. PMID 26900664.

- ^ Crafting a better T cell for immunotherapy. New technology aims to reduce patients’ waiting time, increase potency of T-cell therapy

- ^ أ ب ت Zhang E, Xu H (2017). "A new insight in chimeric antigen receptor‐engineered T cells for cancer immunotherapy". Hematol Oncol. 10 (1). doi:10.1186/s13045-016-0379-6.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Bonini C, Ferrari G (1997). "HSV-TK gene transfer into donor lymphocytes for control of allogeneic graft-versus-leukemia". Science. 276: 1719–1724. doi:10.1126/science.276.5319.1719.

- ^ Quintarelli C, Vera JF (2007). "Co-expression of cytokine and suicide genes to enhance the activity and safety of tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes". Blood. 110: 2793–2802. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-02-072843.

- ^ Riddell SR, Elliott M (1996). "T-cell mediated rejection of gene-modified HIV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in HIV-infected patients". Nat Med. 2: 216–223. doi:10.1038/nm0296-216.

- ^ Maher J, Brentjens RJ (2002). "Human T-lymphocyte cytotoxicity and proliferation directed by a single chimeric TCRζ/CD28 receptor". Nat Biotechnol. 20: 70–75. doi:10.1038/nbt0102-70.

- ^ Liu JC, Voisin V (2012). "Seventeen-gene signature from enriched Her2/Neu mammary tumor-initiating cells predicts clinical outcome for human HER2+: ERα−breast cancer". PNAS. 109: 5832–5837. doi:10.1073/pnas.1201105109.

- ^ Wilkie S, van Schalkwyk MC (2012). "Dual targeting of ErbB2 and MUC1 in breast cancer using chimeric antigen receptors engineered to provide complementary signaling". Clin Immunol. 32: 1059–1070. doi:10.1007/s10875-012-9689-9.

- ^ Wu CY (2015). "Remote control of therapeutic T cells through a small molecule-gated chimeric receptor". Science. 350: aab4077. doi:10.1126/science.aab4077. PMC 4721629.

- ^ Frankel SR (2013). "Targeting T cells to tumor cells using bispecific antibodies". Curr Opin Chem Biol. 17: 385–392. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.03.029.

- ^ Sun LL (2015). "Anti-CD20/CD3 T cell-dependent bispecific antibody for the treatment of B cell malignancies". Sci Transl Med. 7: 287ra70. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa4.

- ^ Kim CH (2013). "Bispecific small molecule-antibody conjugate targeting prostate cancer". PNAS. 110: 17796–17801. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316026110.

- ^ Lee, Yong Gu; Chu, Haiyan; Low, Philip S (2017). "Abstract LB-187: New methods for controlling CAR T cell-mediated cytokine storms". Cancer Research. 77 (13 Supplement): LB-187. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.AM2017-LB-187.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ SMDC TECHNOLOGY.[dead link] ENDOCYTE

- ^ "Endocyte Announces Promising Preclinical Data for Application of SMDC Technology in CAR T Cell Therapy in Late-Breaking Abstract at American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2016" (Press release). Endocyte. April 19, 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةLipowska-Bhalla 2012 953–962 - ^ Sadelain, M.; Gilham David E.; Hawkins Robert E.; Rothwell Dominic G. (2009). "The promise and potential pitfalls of chimeric antigen receptor". Curr Opin Immunol. 21 (2): 215–223. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2009.02.009. PMID 19327974.

وصلات خارجية

CAR T Cells: Engineering Patients’ Immune Cells to Treat Their Cancers