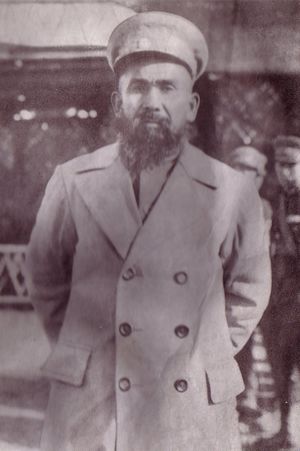

محمود محيطي

Mahmut Muhiti | |

|---|---|

| |

| الاسم المحلي | مەھمۇت مۇھىتى |

| الكنية | Mahmut Shizhang |

| ولد | 1887 Turpan, Xinjiang, Qing Empire |

| توفي | 1944 Beijing, Republic of China |

| الولاء | China (1933) First East Turkestan Republic (1933–34) Xinjiang Provincial Government (1934–37) |

| سنين الخدمة | 1933–37 |

| الرتبة | General |

| الوحدة | 36th Division (1933) |

| قيادات مناطة | Chief, Deputy Chief of Kashgar Military Region (1934) Commander-in-chief of 6th Uyghur Division (1934–37) |

| المعارك/الحروب | Kumul Rebellion |

Mahmut Muhiti (ويغور: مەھمۇت مۇھىتى، أ.ل.أ.: Mehmut Muhiti; الصينية: 马木提·穆依提; پنين: Mǎmùtí Mùyītí; Wade–Giles: Mamut'i Muit'i; 1887–1944), nicknamed Shizhang (الصينية: 师长; پنين: Shīcháng; Wade–Giles: Shih-ch'ang), was an Uyghur warlord from Xinjiang. He was a commander of the insurgents led by Khoja Niyaz during the Kumul Rebellion against the Xinjiang provincial authorities. After Hoya-Niyaz and Sheng Shicai, the newly appointed ruler of Xinjiang, formed peace, Muhiti was briefly appointed by Sheng a Military Commander of the Kashgar region in 1934, but was soon demoted and appointed commander of the 6th Division, composed of Turkic Muslims and named Deputy Military Commander of the Kashgar region. Muhiti opposed Sheng's close ties with the Soviet Union forming opposition to his regime in Kashgar. He organised the Islamic rebellion against Sheng in 1937 and fled to British India. Muhiti was afterwards active in the Japanese-occupied China, fruitlessly cooperating with Japan in order to enhance the cooperation between Japan and Muslims, dying in Beijing.

خلفية

Muhiti was born in 1887,[1] to a wealthy family.[2] Little is known about his personal life. British consul K. C. Packman described him as "a wealthy but intriguing and unreliable ex-merchant from Turpan". Packman's successor Thomson-Glover said that Muhiti "was a simple and kindly man, and a zealous Mohammedan".[3] He ran a cotton business with the Soviet Union and was a long time Jadidist.[2] His brother Mekhsut[1] (1882–1932)[4] was a Jadidist activist.[1]

تمرد قومول

At the end of 1932, Muhiti was one of the leaders of the insurrection in Turpan, along with his brother and Tahir Beg and Yunus Beg against the Xinjiang provincial authorities.[5] The group that initiated the revolt in Turpan was a secret organisation led by Muhiti's brother Mekhsut,[6] who was killed during the rebellion (his head was cut off by White Russian Guards, mobilized in 1932 into Xinjiang Provincial Army by Governor Jin Shuren).[1] The rebels fought furiously,[5] and by January 1933 most of the city was in rebels' hands.[2]

Leaders of the local uprisings were nominally placed within the 36th Division of the National Revolutionary Army, a regular Chinese army by Ma Shiming, a deputy of Ma Zhongying. Between 1933 and 1934 Muhti was the chief military commander of the Khoja Niyaz's forces.[7]

Soviet Union decided to aid the Xinjiang provincial government and sent some 2,000 Chinese soldiers forced by Japanese across the Soviet border and interned by the Soviets. These Chinese soldiers were known as the North-East National Salvation Army.[8] Their arrival coincaded with the brake of relations between Ma Shiming and Turkic rebels in Turpan. Soon, Sheng Shicai, Chief of Staff of the Xinjiang's Frontier Army, restored the provincial authority in Turpan.[2]

A group of survivors from Turpan, including Muhiti, regrouped with Hoja-Niyaz in Hami. Using the opportunity during a coup in the provincial capital of Ürümqi against Xinjiang's Governor Jin Shuren, Hoja-Niyaz led his forces towards Turpan in April. They proclaimed themselves as the Xinjiang Citizens Revolutionary Army and wrote to the Central government in Nanking justifying their response to Jin's tyranny.[9] At the same time, Ma Zhongying was advancing from the east towards Ürümqi. However, Hoja-Niyaz's anxiety about Ma Zhongying's ambitions were compounded by conflicts over arms and ammunitions. This led to discord between the two Muslim leaders.[2]

Newly appointed provincial administration, de facto led by Duban or Military Governor Sheng Shicai, entered negotiations with Hoja-Niyaz. Previously they tried to drive a wedge between the two rebel leaders by offering Ma Zhongying military supremacy over Tarim Basin. Hoja-Niyaz was offered partition of Xinjiang into north and south, where Hami and Turpan would be controlled by Muslims.[10]

Meanwhile, in February 1933, a rebellion erupted in Khotan. They were joined by Turkish-educated nationalists who founded the Independence Association. In November 1933, the Independence Association proclaimed the East Turkestan Republic (ETR), with Sabit Damulla as Prime Minister and surprisingly appointing Hoja-Niyaz, theoretically aligned with Ürümqi, as President in absentia.[11] Hoja-Niyaz accepted the presidency. However, not long after taking the position, he met with Soviet officials who instructed him to prove his reliability by bringing in the ETR's anti-Soviet Prime Minister Damulla. Hoja-Niyaz obliged and rendered Damulla to the Soviets who executed him.[12]

Ma Zhongying sieged Ürümqi for the second time in January 1934. This time, the Soviets sent military aid to Sheng. With the Soviet assistance, Sheng again defeated Ma Zhongying's forces, who retreated south from Tien Shan, in a region controlled by the ETR.[13] In February Ma Zhognyang's forces arrived in Kashgar, extinguishing the ETR. Hoja-Niyaz escaped upon the arrival of Ma Zhongying's troops[13] and left Muhiti, his second in command in Kashgar Old City.[14] In Irkeshtam Hoja-Niyaz signed an agreement that abolished the ETR and supported the Sheng's regime.[13] He was appointed Deputy Chairman of Xinjiang.[14] Muhiti supported the ceasefire agreement between Hoja-Niyaz and Sheng, which enabled him to hold a senior military post after the rebellion.[7]

الخدمة في قشغر

Two weeks after Ma Zhongying left for the Soviet territory,[15] in early July 1934,[3] Kashgar was occupied by a unit of 400 Chinese soldiers under the command of Kung Cheng-han[15] on 20 July.[3] He was accompanied by the 2,000 strong Uighurs commanded by Muhiti. Thus, Kashgar came under the control of the Xinjiang's provincial authority after almost a year.[16] After the arrest or flight of the ETR authorities, many Muslims in the region looked to Muhiti for a leadership.[3]

In order to reassure the local population and to allow himself further time to consolidate his power in the northern and eastern part of the province, Sheng appointed Muhiti as overall Military Commander for the Kashgar region.[3] Muhiti formed the new administration in Kashgar known as the National Assembly.[14] Sheng wasn't comfortable with the Muslim officials in Kashgar, and thus a month later, he appointed his fellow Manchurian Liu Pin to the position of Commanding Officer in Kashgar. Muhiti was demoted and retained the poisiton of Divisional Commander.[3] He was rendered with a force of 2,000 Turkic troops.[17] He became known as Mahmut Shizhang, a Mandarin term for a division commander.[2]

Sheng's Han Chinese appointees took the effective control over the Kashgar region, and foremost amongst them was Liu, a Chinese nationalist and a Christian. Liu understood little about the local Muslim culture. Immediately upon his arrival he ordered that the picture of Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the Chinese Republic, be hung in the Kashgar mosque. The local Muslim population was dismayed by the developments in Kashgar and considered that the "Bolsheviks had taken over the country and were bent on destroying religion". In addition, Sheng's educational reform which attacked some Islamic principles further alienated the Muslim population.[18]

The top priority of Muhiti's was schooling.[14] The Uyghur Enlightenment Association was formed under the aegis of the Society for the Promotion of Education, a body that was revived during the ETR and carried on the legacy of earlier Jadidist societies. Abdulkarim Khan Makhdum, former Minister of Education of the ETR, continued to play an important role in educational work of Muhiti's Kashgar administration. The Uyghur Enligtenment Association started its work in April 1935, and took responsibility for publishing and schooling in Kashgar, significantly increasing availability of primary schooling. To fund this work, the association took control over the Kashgar's zakat (Islamic charity) and waqf, redirecting the wealth of local shrines to textbooks and teachers. Qadir Haji, chief of police in Kashgar Old City, was amongst those who contributed to Muhiti's educational push. He raised funds and founded a school in Qaziriq, his native village.[19]

The Uyghur Enlightenment Association issued New Life, which published a series of articles dealing with significance of the Uyghur etnonym to its readers.[19] The activity of the Uyghur Enligtenment Association raised suspicion amongst the Soviet officials who become worried about the rise of Uyghur nationalism.[20]

Meanwhile, surviving officials of the ETR began to assamble in Kabul, Afghanistan, where they lobbied the Afghan government and certain embassies, most notably the Japanese, for backing. Japanese Ambassador Kitada Masamoto provided audience for these anti-communist emigres. In mid 1935, Kitada was visited by Muhammad Amin Bughra, a former Khotan emir. Bughra submitted the ambassador a detailed plan about establishing the East Turkestan Republic under Japanese sponsorship, which would in return for independence, give Japan special economic and political privileges. He proposed Muhiti as future leader of the proposed puppet state.[21]

Muhiti became the focal point of the opposition to the Sheng's government.[22] From the middle of 1936, he and his supporters began to propagate the idea of creating an "independent Uyghur state". In this case, he was supported by Muslim religious leaders and influential people from Xinjiang. Muhiti, having entered into contact with the Soviet consul in Kashgar Smirnov, even tried to get weapons from the Soviet Union, but his appeal was rejected. Then, by contacting former Dungan opponents, in early April 1937, Muhiti was able to raise an uprising against the Xinjiang authorities. However, only two regiments of the 6th Uygur Division, stationed near Kashgar, came out in his defence, while the other two regiments declared their loyalty to the Sheng's government.[23]

In Kashgar, the tensions were high. Muhiti and his circle increasingly clashed with the pro-Soviet elements, among them Qadir Haji. Hoja-Niyaz's associate Mansur Effendi arrived in Kashgar in 1935 in order to seize control over the finances of the Uyghur Enligtenment Association. He failed to do so, but succeeded in appointing a Chinese communist to the editorship of the New Life, thus neturalising it as the anti-government organ. Kashgar's qadi Abdulghafur Damulla, who was seen as close to Qadir Haji, was assassinated in May 1936. Soviet General Consul Garegin Apresov visited Muhiti in Kashgar and accused him of seeking Japanese support.[20]

Urged by the Soviets, Sheng's government sent a peacekeeping mission to Kashgar to resolve the conflict. The negotiations, however, did not took place. The Soviets tried to contact Ma Hushan, new commander of the Dungan 36th Division, via Ma Zhongying, to disarm Muhiti's rebels.[24] However, Muhiti, with 17 of his associates fled to British India[24] after Sheng summoned him to the Third Congress of People's Representatives in 1937.[20]

الحياة في المنفى

Muhiti left for British India on April 2 1937, crossing into لداخ and by-passing the Karakoram Pass by going up the Karakash River and to Aksai Chin and then following the road through Chang La arrived in Leh, where he turned up on 27 April. Around four weeks later he arrived in Srinagar. He went on pilgrimage to Mecca in January 1938.[25]

After Muhiti's flight, a coalition between Hoja-Niyaz and Sheng broke up. A new rebellion started in Kashgar[26] led by the two of Muhiti's officers Kichik Akhund and 'Abd al-Niyas[27] and supported by Dungans of the 36th Division, now commanded by Ma Hushan.[26] The revolt was Islamic in its nature.[22]

Abdul Niyaz succeeded Muhiti and was proclaimed a general. Niyaz took Yarkand and moved towards Kashgar, eventually capturing it.[24] Those with pro-Soviet inclinations were executed and thus new Muslim administration was established.[22] Simultaneously, the uprising spread amongst the Kirghiz near Kucha and Hami.[22] After capturing Kashgar, Niyaz's forces started to move towards Karashar, receiving assistance from the local population along the way.[28]

In order to jointly fight against the Soviets and Chinese, Niyaz and Ma Hushan signed a secret agreement on 15 May.[28] Ma Hushan used the opportunity and moved from Khotan to take over Kashgar from the rebels in June,[22] as promulgated by the agreement.[28] However, 5,000 Soviet troops, including airborne and armoured vehicles were marching towards southern Xinjiang on Sheng's invitation along with Sheng's forces and Dungan troops.[22]

The Turkic rebels were defeated and Kashgar retaken.[22] After the defeat of the Turkic rebels, the Soviets also stopped maintaining the 36th Division.[29] Ma Hushan's administration collapsed. By October 1937, along with the collapse of the Turkic rebellion and the Tungan satrapy, the Muslim control over the southern part of the province ended. Soon afterwards, Yulbars Khan troops in Hami were also defeated ( upon starting of Rebellion of 6th Uyghur Division in Kashgar in April 1937 rebels appealed to Yulbars Khan to cut off communications between Xinjiang and China through Kumul or Hami). Thus, Sheng became the ruler of the whole province for the first time.[22]

The uprising was crushed after the Soviet intervention.[30] Ma Hushan also escaped to British India after the rebellion was defeated. The presence of Muhiti and Ma Hushan in British India was interpreted as evidence of British interference in Xinjiang politics, which led to Chinese closing off the two main trade offices in India, in Gilgit and Leh.[31]Trade office in Leh, which with years lost its importance, remained closed, while in Gilgit was soon reopened.[32]

After arriving in British India, Muhiti left for Mecca, Saudi Arabia and was reported to be in Japan in 1940,[7] where he founded the Independence Society, which had a goal of establishing East Turkestan, opposed both to the Soviet Union and China.[33] Muhiti once again gained the Japanese confidence for cooperation in early 1939. The next year he went to China, ending an extensive tour there in Suiyuan Province (present Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China) in October 1940. While in China, Muhiti promoted a pan-Muslim movement under the auspices of the Japan-Islam society, previously established in Tokyo. The goal of the society was cultural and economic cooperation between Japan and Muslims. Muhiti planned to establish the Xinjiang Uyghur Society, seated in Tokyo with its branches all across Inner Asia. However, the Japanese support for Muhiti was fruitless.[34]

Muhiti died in the Japanese-occupied Beijing in 1944 from a brain hemorrhage, and is buried in a Muslim cemetery there.[33]

الهامش

- ^ أ ب ت ث Klimeš 2015, p. 121.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Brophy 2016, p. 240.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Forbes 1986, p. 138.

- ^ Klimeš 2015, p. 81.

- ^ أ ب Dudoignon & Hisao 2001, p. 138.

- ^ Dudoignon & Hisao 2001, p. 139.

- ^ أ ب ت Forbes 1986, p. 247.

- ^ Forbes 1986, p. 104.

- ^ Brophy 2016, p. 242.

- ^ Brophy 2016, p. 242–243.

- ^ Brophy 2016, p. 243–244.

- ^ Brophy 2016, p. 244.

- ^ أ ب ت Clarke 2011, p. 32.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Brophy 2016, p. 254.

- ^ أ ب Forbes 1986, p. 126.

- ^ Forbes 1986, p. 126–127.

- ^ Forbes 1986, p. 137–138.

- ^ Forbes 1986, p. 139.

- ^ أ ب Brophy 2016, p. 261.

- ^ أ ب ت Brophy 2016, p. 262.

- ^ Forbes 1986, p. 140.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Dickens 1990, p. 17.

- ^ Gasanli 2016, p. 74–75.

- ^ أ ب ت Gasanli 2016, p. 76.

- ^ Lamb 1991, p. 66.

- ^ أ ب Brophy 2016, p. 262–263.

- ^ Forbes 1986, p. 141.

- ^ أ ب ت Gasanli 2016, p. 77.

- ^ Gasanli 2016, p. 72.

- ^ Brophy 2016, p. 263.

- ^ Lamb 1991, p. 66–67.

- ^ Lamb 1991, p. 67.

- ^ أ ب Tunces 2019, p. 130.

- ^ Whiting & Sheng 1958, p. 64.

المراجع

كتب

- Clarke, Michael E. (2011). Xinjiang and China's Rise in Central Asia - A History. Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781136827068.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dudoignon, Stéphane A.; Hisao, Komatsu (2001). Islam in Politics in Russia and Central Asia: (early Eighteenth to Late Twentieth Centuries). Abingdon-on-Thames: Kegan Paul. ISBN 9780710307675.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Forbes, Andrew D. W. (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521255141.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gansali, Jamil (2016). Синьцзян в орбите советской политики: Сталин и муслиманское движение в Восточном Туркестане 1931-1949 [Xinjiang in the orbit of Soviet politics: Stalin and the Muslim movement in East Turkestan 1931-1949] (in Russian). Moscow: Флинта. ISBN 9785976523791.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Klimeš, Ondřej (2015). Struggle by the Pen: The Uyghur Discourse of Nation and National Interest, c.1900-1949. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004288096.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lamb, Alastair (1991). Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy, 1846-1990. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195774238.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Whiting, Allen Suess; Sheng, Shicai (1958). Sinkiang: pawn or pivot?. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

دوريات

- Tuncer, Tekin (2019). "Hamidullah Muhammed Tarım'ın "Türkistan Tarihi-Türkistan 1931-1937 İnkılâp Tarihi" Adlı Eserinde Mehmet Emin Buğra". SUTAD (45): 127–141.

وصلات خارجية

- Dickens, Mark (1990). "The Soviets in Xinjiang 1911-1949" (PDF). Oxus Communications. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)