قائمة أعمال ليوناردو دا ڤنشي

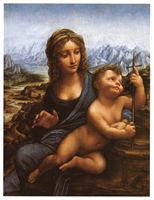

Leonardo da Vinci (baptised Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci pronunciation ; April 15, 1452 – May 2, 1519) was one of the leading artists of the High Renaissance. Fifteen artworks are generally attributed either in whole or in large part to him. Most are paintings on panel, with the remainder being a mural, a large drawing on paper, and two works in the early stages of preparation. The authorship of several paintings traditionally attributed to Leonardo is disputed. Two major works are known only as copies. Works are regularly attributed to Leonardo with varying degrees of credibility. None of Leonardo's paintings are signed. The attributions here draw on the opinions of various scholars.[1]

The small number of surviving paintings is due in part to Leonardo's frequently disastrous experimentation with new techniques and his chronic procrastination. Nevertheless, these few works together with his notebooks, which contain drawings, scientific diagrams, and his thoughts on the nature of painting, comprise a contribution to later generations of artists rivalled only by that of his contemporary, Michelangelo.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الأعمال الكبرى المتواجدة

| Image (sort by size of the original) |

Details (sort by title) |

Attribution status and notes | Dating (sort by earliest) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

Forensic and scientific analysis by M. Seracini now proves that the paint was not applied by da Vinci, but considerably later, so that only the sketch can be "universally accepted" (see M. Henneberger https://www.nytimes.com/2002/04/21/magazine/the-leonardo-cover-up.html. Archives | 2002, The New York Times Magazine, 21 April 2002, "The Leonardo Cover-Up"). Carlo Pedretti, the greatest da Vinci scholar states that the results are unambiguous: "From what he showed me ... it's clear that Leonardo's original sketch was gone over by an anonymous painter." Pedretti adds that he was surprised, though not disappointed, that the news was finally getting out - "it's extremely important and should be said because it has to be clarified." |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

نسب متنازَع عليه

| الصورة | التفاصيل | ملاحظات | تأريخ |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

||

|

|||

|

|

|

أعمال مفقودة

| التفاصيل | ملاحظات | الصورة |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

منسوبات مؤخراً

| الصورة | التفاصيل | وضع النسب |

|---|---|---|

|

Recently the subject of a new book (2017) and attributed to Leonardo and workshop by Professor Carlo Pedretti. Previously incorrectly attributed only to his student Giampetrino. Mentioned by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres in 1845 and by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, who were both convinced that it was a Leonardo original. According to the world's top Leonardo expert Carlo Pedretti, the so-called Cheramy Madonna "is wholly similar to the one in the Louvre" (see http://www.italymagazine.com/italy/marche/virgin-rocks-smash-hit, Italy Magazine, "Virgin of the rocks a smash hit," 9 November, 2005). Pedretti says the work - only recently recovered from another private collection - shows "clear signs" of the master's hand at work just four years before his death. Following detailed restoration of the work, Pedretti is convinced that it is an original Leonardo (Leonardo da Vinci : the "Virgin of the rocks" in the Cheramy version : its history & critical fortune, by Carlo Pedretti and Sara Taglialagamba, 2017). | |

|

| |

|

| |

|

Previously attributed by Sotheby's to Gian Francesco Maineri.[29][30] Attributed to Leonardo by its former owner.[29] Attribution based on the similarity of the tormentors of Christ to drawings made by Rubens of the Battle of Anghiari. According to Forbes Magazine, Leonardo expert Carlo Pedretti said that he knew of three similar paintings and that "All four paintings, he believed, were likely the work of Leonardo's studio assistants and perhaps even the master himself."[29] | |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

المخطوطات

| الصورة | العنوان | التواريخ | الصفحات | ملاحظات | الموقع |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codex Atlanticus | 1478–1519 | 1,119 | 12 volumes, collated by the sculptor Pompeo Leoni. | Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana | |

| Codex Windsor | 1478–1518 | 153 | Windsor, Royal Collection | ||

| Codex Arundel | 1480–1518 | 283 | London, British Library | ||

| Codex Trivulzianus | c. 1487–90 | 55 (originally 62) | Milan, Biblioteca Trivulziana, Castello Sforzesco | ||

| Codex Forster | 1487–1505 | 354 | Five pocket notebooks bound into three volumes, here listed in chronological order.

|

London, Victoria and Albert Museum | |

| Paris Manuscripts | 1488–1505 | more than 2500 |

12 volumes labeled from "A" to "M", here listed in chronological order.

|

Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France | |

| Codex Madrid | 1490s–1504 | Two volumes, rediscovered in 1966.

|

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España | ||

| Codex Ashburnham | ح. 1492 | Two volumes, taken out of Paris Manuscripts A and B and sold to the Earl of Ashburnham, who returned them to Paris in 1890. | Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France | ||

| Codex on the Flight of Birds | dated 1505 | 18 | Originally part of Paris Manuscript B; probably stolen by Count Guglielmo Libri in around 1840–7.[57] | Turin, Biblioteca Reale | |

| Codex Leicester | 1506–1510 | 72 | United States, private collection | ||

| Codex Urbinas | c. 1530 | An anthology of writings by Leonardo compiled after his death by his pupil Francesco Melzi. An abridged version was published in 1651 as a treatise on painting (Trattato della Pittura).[58] | Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana |

المراجع

مصادر لوضع النسب

- ^ Portrait of a Musician: Leonardo da Vinci (Kemp 2011, p. 254); Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio (?) and Leonardo (?) (Zöllner 2011, p. 225)

- ^ Buccleuch Madonna: Leonardo da Vinci and an anonymous 16th-century painter (Syson 2011, p. 294); Workshop of Leonardo after a design by Leonardo (Zöllner 2011, p. 239)

- ^ Lansdowne Madonna: Salaì after a design by Leonardo (Zöllner 2011, p. 238)

- ^ La Scapigliata: Follower of Leonardo (Syson 2011, p. 198, n. 9); “ascribed today to Leonardo” (Marani 2000, p. 140)

الذِكر

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز

della Chiesa, Angela Ottino (1967). The Complete Paintings of Leonardo da Vinci. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-008649-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, 1568; this edition Penguin Classics, trans. George Bull 1965, ISBN 0-14-044164-6

- ^ "National Gallery in London accused of altering attribution of Hermitage's 'Leonardo' for 2011 blockbuster show". www.theartnewspaper.com. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- ^ M. Kemp, entry for The Lady with an Ermine in the exhibition Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration (Washington-New Haven-London) pp 271f, states "the identification of the sitter in this painting as Cecilia Gallerani is reasonably secure;" Janice Shell and Grazioso Sironi, "Cecilia Gallerani: Leonardo's Lady with an Ermine" Artibus et Historiae 13 No. 25 (1992:47-66) discuss the career of this identification since it was first suggested in 1900.

- ^ أ ب Marani 2000, p. 339

- ^ Kemp 2011, 253

- ^ Syson 2011, 294

- ^ For a partial list of scholars who accept the attribution, see Bailey, Martin (31 October 2011). "Leonardo's Saviour of the World rediscovered in New York". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

- ^ Syson 2011, 302

- ^ Andrews, Travis M. (15 November 2017). "Long-lost da Vinci painting fetches $450 million, a world record". Washington Post. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ Holland, Oscar. "Rare Da Vinci painting smashes world records with $450 million sale". CNN. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ "Who Really Painted 'Salvator Mundi'? An Oxford Art Historian Says It Was Leonardo's Assistant | artnet News". artnet News (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2018-08-07. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- ^

Arasse, Daniel (1997). Leonardo da Vinci. Konecky & Konecky. ISBN 1-56852-198-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Kemp, Martin (2004). Leonardo. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 251. The work does not appear in Kemp 2011.

- ^ Adams, James (October 13, 2005). "Montreal art expert identifies da Vinci drawing". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2009-10-14.

- ^ "The Mark of a Masterpiece" by David Grann, The New Yorker, vol. LXXXVI, no. 20, July 12 & 19, 2010, ISSN 0028-792X

- ^ Byrne, Paul (2015-11-30). "Portrait hailed as Da Vinci masterpiece is actually grumpy Bolton checkout girl". mirror. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

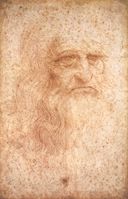

- ^ Scaramella, A. D. "Artwork Analysis self Portrait in Red Chalk by Leonardo Da Vinci". Finearts.com. Helium Inc. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Emergency Treatment for Leonardo da Vinci's Self-Portrait". news.universityproducts.com. Archival Products. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Marani 2000, p. 431

- ^ Rubin & Wright 1999, pp. 84 and 118, n. 25

- ^ Shearman, John (1992). Only Connect...: Art and the Spectator in the Italian Renaissance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 33.

- ^ Delieuvin 2012, cat. 80

- ^ Delieuvin 2012, cat. 81

- ^ "St John the Baptist". Your Paintings. BBC. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ Arie, Sophie (16 February 2005). "Fingerprint puts Leonardo in the frame". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ^ "A lost Leonardo? Top art historian says maybe". Universal Leonardo. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ^ Bertelli, Carlo (November 19, 2005). "Due allievi non fanno un Leonardo" (in Italian). Il Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ أ ب ت Stephane Fitch DaVinci's Fingerprints, 12.22.03 accessed 7 July 2009. Martin Kemp, the expert on Leonardo's fingerprints, had not examined the painting when the article was written.

- ^ A similar image, without the tormentors, is in the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. [1][dead link]

- ^ Self-portrait of Leonardo, Surrentum Online, accessed 2010-11-06

- ^ "'Early Mona Lisa' painting claim disputed". BBC News. 27 September 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ "'Horse and Rider' Discovered Leonardo Da Vinci Sculpture". Huffington Post. 14 August 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Remarkable 500-year-old Leonardo Da Vinci casting of horse and rider unveiled after original was lost for centuries". Daily Mail News. 29 August 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Leonardo da Vinci's 'Horse and Rider'". BBC News. 28 August 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Zerner, Henri (25 September 1997). "The Vision of Leonardo". The New York Review of Books. 44 (14): 67.

no existing sculpture can be attributed to him with any certainty. [... the Bust of Christ as a Youth] was unfortunately placed in the exhibition next to a bizarre object, a wax statuette of a rider on a bucking horse never before seen in public. In the explanatory label, the statuette was said to have belonged to Francesco Melzi, a student and companion of Leonardo, a provenance unfortunately based on hearsay. [...] I fail to see the point of presenting to the uninformed visitor highly debatable hypotheses as if they were confirmed.

- ^ Holmstrom, David (24 March 1997). "Putting Leonardo's Inventions to the test: Boston's Museum of Science looks at the breathtaking scope of Leonardo da Vinci's work, though the authenticity of some objects is in question". The Christian Science Monitor.

CONTROVERSIAL WORK: Whether Leonardo made this small wax figure is a source of contention among experts. Although the piece is unsigned, it is attributed to him in the exhibit.

(يتطلب اشتراك) - ^ Yemma, John (23 February 1997). "Leonardo on tour: the good, the bad ... and the phony? Art historians question attribution of some works headed for Boston show". The Boston Globe. p. A.1.

at least one of the two sculptures on display in the art gallery at Science Park beginning March 3 have caused grave doubts among some art historians. [...] The labels on the paintings, Ackerman warned museum officials, were simply too generous, linking dubious and contested works from private collections too closely with Leonardo and other Italian masters. [...] after weeks of struggling over wording, museum officials altered some of the labels to introduce more skepticism [... The Wax Horse] is "attributed to Leonardo." Not so fast, said Jack Wasserman, an art historian at Temple University in Philadelphia. "There is no single work of sculpture which Leonardo worked on that survived to today," Wasserman said. "Yes, it could be 'attributed to' Leonardo, but you need to have a compelling reason for doing so. Since nothing survived, there is no way to judge a piece of sculpture like this."

(يتطلب اشتراك) - ^ Panza, Pierluigi (19 October 2016). "La scultura equestre di Leonardo Esposizione tra genio e mistero". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). Retrieved 1 March 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Gatti, Chiara (19 October 2016). "Arriva l'uomo a cavallo di Leonardo Da Vinci che divide i critici". la Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 22 February 2017.

Presentata come una rivelazione esclusiva, è contestata da molti esperti. [...] Vittorio Sgarbi non nasconde i suoi dubbi sull'attribuzione al maestro toscano [...] Pietro Marani: Non ci sono evidenze, né si possono fare confronti poiché non esistono dati d'appoggio, esemplari sicuri.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Sturman, Shelley; May, Katherine; Luchs, Alison (2017). "The Budapest Horse: Beyond the Leonardo da Vinci Question". In Helmstutler Di Dio, Kelley (ed.). Making and Moving Sculpture in Early Modern Italy. Routledge. p. 27. ISBN 9781351559515.

- ^ "The Forster Codices: Leonardo da Vinci's Notebooks at the V&A". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ "Paris Manuscript B". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "Paris Manuscript C". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "Paris Manuscript A". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "Paris Manuscript H". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "Paris Manuscript M". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "Paris Manuscript L". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "Paris Manuscript K". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "Paris Manuscript I". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "Paris Manuscript D". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "Paris Manuscript F". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "Paris Manuscript E". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "Paris Manuscript G". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "Codex Madrid I". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "Codex Madrid II". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ Bambach 2003, p. 723

- ^ "Codex Urbinas and lost Libro A". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

ببليوگرافيا

- Bambach, Carmen C., ed (2003). Leonardo da Vinci: Master Draftsman. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Chapman, Hugo; Faietti, Marzia (2010). Fra Angelico to Leonardo: Italian Renaissance Drawings. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2667-8.

- Covi, Dario A. (2005). Andrea del Verrocchio: Life and Work. Arte e archeologia: Studi e documenti. Florence: Leo S. Olschki Editore.

- Delieuvin, Vincent, ed. (2012). Saint Anne: Leonardo da Vinci’s Ultimate Masterpiece. Milan: Officina Libraria.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kemp, Martin (2006). Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1992-0778-7.

- Kemp, Martin (2011). Leonardo: Revised edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Marani, Pietro C. (2000). Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc..

- Rubin, Patricia Lee; Wright, Alison (1999). Renaissance Florence: The Art of the 1470s. London: National Gallery Publications.

- Syson, Luke; Larry Keith; Arturo Galansino; Antoni Mazzotta; Scott Nethersole; Per Rumberg (2011). Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan. London: National Gallery.

- Zöllner, Frank (2011). Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings and Drawings. 1. Cologne: Taschen.

Leonardo da Vinci : the "Virgin of the rocks" in the Cheramy version : its history & critical fortune, by Carlo Pedretti and Sara Taglialagamba, 2017.

وصلات خارجية

- Leonardo da Vinci and the Virgin of the Rocks, A different point of view

- Web Gallery of Leonardo Paintings

- Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci

- Leda and the Swan copies by Leonardaschi

- Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman, exhibition catalog fully online as PDF from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Leonardo da Vinci: anatomical drawings from the Royal Library, Windsor Castle, exhibition catalog fully online as PDF from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- The Codex Arundel on the British Library's Digitised Manuscripts Website