غوانغ زوان، المنطقة المستأجرة

21°10′38.2″N 110°25′4.76″E / 21.177278°N 110.4179889°E

Kouang-Tchéou-Wan 廣州灣 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1898–1945 | |||||||||

العلم | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Location of Kwangchow Wan in French Indochina | |||||||||

| الوضع | Leased territory of France | ||||||||

| العاصمة | Fort-Bayard | ||||||||

| اللغات المشتركة | |||||||||

| الحقبة التاريخية | New Imperialism | ||||||||

• French occupation | 22 April 1898 | ||||||||

• Leased by France | 29 May 1898 | ||||||||

• Administered by French Indochina | 5 January 1900 | ||||||||

• Occupied by Japan | 21 February 1943 | ||||||||

• Returned by France | 18 August 1945 | ||||||||

| المساحة | |||||||||

| 1,300 km2 (500 sq mi) | |||||||||

| التعداد | |||||||||

• 1911 | 189,000 | ||||||||

• 1935 | 209,000 | ||||||||

| العملة | French Indochinese piastre | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| غوانغ زوان، المنطقة المستأجرة | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الصينية التقليدية | 廣州灣 | ||||||||||||

| الصينية المبسطة | 广州湾 | ||||||||||||

| المعنى الحرفي | Guangzhou Bay | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

گوانگژووان، المنطقة المستأجرة Leased Territory of Guangzhouwan، واسمها الرسمي Territoire de Kouang-Tchéou-Wan,[nb 1] was a territory on the coast of Zhanjiang in China leased to France and administered by French Indochina.[1] The capital of the territory was Fort-Bayard, present-day Zhanjiang.[nb 2]

The Japanese occupied the territory in February 1943. In 1945, following the surrender of Japan, France formally relinquished Guangzhouwan to China. The territory did not experience the rapid growth in population that other parts of coastal China experienced, rising from 189,000 in the early 20th century[2] to just 209,000 in 1935.[3] Industries included shipping and coal mining.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الجغرافيا

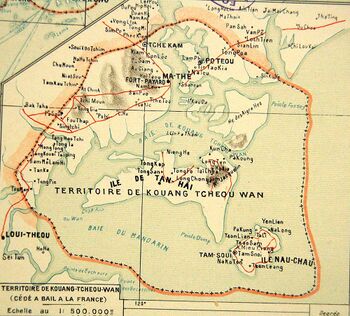

The leased territory was situated on the east side of the Leizhou Peninsula (فرنسية: Péninsule de Leitcheou), near Guangzhou, around a bay then called Kwangchowan, now called the Port of Zhanjiang. The bay forms the estuary of the Maxie River (صينية: 麻斜河؛ پنين: Máxié hé�, فرنسية: Rivière Ma-The), now known as the Zhanjiang Waterway (صينية: 湛江水道؛ پنين: Zhànjiāng shuǐdào�). The Maxie is navigable as far as 19 kilometres (12 mi) inland even by large warships.

The territory leased to France included the islands lying in the bay, which enclosed an area 29 km long by 10 km wide and a minimum water depth of 10 metres. The islands were recognized at the time as an admirable natural defense, the main islands being Donghai Dao. On the smaller Naozhou Island farther to the southeast, a lighthouse was constructed.

The limits of the territory inland were fixed in November 1899; on the left bank of the Maxie, France gained from Gaozhou prefecture (Kow Chow Fu) a strip of territory 18 kilometres (11 mi) by 10 kilometres (6.2 mi), and on the right bank a strip 24 kilometres (15 mi) by 18 kilometres (11 mi) from Leizhou prefecture (Lei Chow Fu).[2] The total land area of the leased territory was 1,300 square kilometres (500 sq mi).[3] The city of Fort-Bayard (Zhanjiang) was developed as a port.

التاريخ

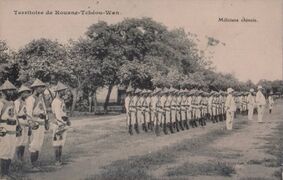

الاحتلال الفرنسي والتنمية المبكرة

Kwangchouwan was leased to the French for 99 years, or until 1997 (as the British did in Hong Kong's New Territories) according to the Treaty of 29 May 1898, ratified by China on 5 January 1900. The colony was described as "commercially unimportant but strategically located"; most of France's energies went into their administration of the mainland of French Indochina, and their main concern in China was the protection of Roman Catholic missionaries, rather than the promotion of trade.[1] Kwangchow Wan, while not a constituent part of Indochina, was effectively placed under the authority of the French Resident Superior in Tonkin (itself under the Governor-General of French Indochina, also in Hanoi); the French Resident was represented locally by Administrators.[4] In addition to the territory acquired, France was given the right to connect the bay by railway with the city and harbour situated on the west side of the peninsula; however when they attempted to take possession of the land to build the railway, forces of the provincial government offered armed resistance. As a result, France demanded and obtained exclusive mining rights in the three adjoining prefectures.[2] The return of the leased territory to China was promised after the First World War by the French at the Washington Naval Conference of 1921–1922 and ultimately returned.[5]

By 1931, the population of Kwangchow Wan had reached 206,000, giving the colony a population density of 245 persons per km2; virtually all Chinese, and only 266 French citizens and four other Europeans were recorded as living there.[3] Industries included shipping and coal mining.[4] The port was also popular with smugglers; prior to the 1928 cancellation of the American ban on the export of commercial airplanes, Kwangchow Wan was also used as a stop for Cantonese smugglers transporting military aircraft purchased in Manila to China,[6] and US records mention at least one drug smuggler who picked up opium and Chinese emigrants to be smuggled into the United States from there.[7]

الحرب العالمية الثانية

As an adjunct of French Indochina, Kwangchow Wan generally endured the same fate as the rest of the Indochina colony during World War II. Even before the signing of the 30 August 1940 accord with Japan in which France recognized the “privileged status of Japanese interests in the Far East” and which constituted the first step of the Japanese military occupation of Indochina, a small detachment of Japanese marines had landed at Fort-Bayard without opposition in early July and set up a control and observation post in the harbor.[8] However, as in the rest of French Indochina, the civilian administration of the territory was to remain in the hands of officials of Vichy France following the Fall of France; in November 1941, Governor-General Jean Decoux, newly appointed by Marshal Pétain, made an official visit to Kwangchow Wan.[9]

In mid-February 1943, the Japanese, after having informed the Vichy government that they needed to strengthen the defence of Kwangchow Wan Bay, unilaterally landed more troops and occupied the airport and all other strategic locations in the Territory. From then on, Kwanchow Wan was de facto under full military Japanese occupation and the French civilian administration was gradually reduced to a mere façade. The Administrator resigned in disgust and Adrien Roques, a local pro-Vichy militant, was appointed to replace him.[10] In May of the same year, Roques signed a convention with the local Japanese military authorities in which the French authorities promised to cooperate fully with the Japanese. On 10 March 1945, the Japanese, following up on their sudden attack on French garrisons throughout Indochina the night before, disarmed and imprisoned the small French colonial garrison in Fort-Bayard.[11] Just prior to the Japanese surrender, Chinese forces were prepared to launch a large-scale assault on Kwangchow Wan; however, due to the end of the war, the assault never materialised.[12] While the Japanese were still occupying Kwangchow Wan following the surrender, a French diplomat from the Provisional Government of the French Republic and Kuo Chang Wu, Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of China, signed the Convention between the Provisional Government of the French Republic and the National Government of China for the retrocession of the Leased Territory of Kouang-Tchéou-Wan. Almost immediately after the last Japanese occupation troops had left the territory in late September, representatives of the French and the Chinese governments went to Fort-Bayard to proceed to the transfer of authority; the French flag was lowered for the last time on 20 November 1945.[13]

During the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, Kwangchow Wan was often used as a stopover on an escape route for civilians fleeing Hainan and Hong Kong and trying to make their way to Thailand, North America and Free China; Patrick Yu, a prominent trial lawyer, recalled in his memoirs how a Japanese military officer helped him to escape in this way.[14] However, the escape route was closed when the Japanese occupied the area in February 1943.[15]

اللغة الفرنسية

A French-language school, École Franco-Chinoise de Kouang-Tchéou-Wan, as well as a branch of the Banque de l'Indochine, were set up in Fort-Bayard.[16] In addition, a Roman Catholic church constructed during the French occupation is still preserved today.[17]

معرض

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

المراجع

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الهامش

- ^ أ ب Gale 1970, p. 201.

- ^ أ ب ت Chisholm 1911.

- ^ أ ب ت Priestly 1967, p. 441.

- ^ أ ب Olson 1991, p. 349.

- ^ Escarra 1929, p. 9.

- ^ Xu 2001, p. 21.

- ^ Anslinger & Tompkins 1953, p. 141.

- ^ Matot 2013, p. 193.

- ^ Matot 2013, p. 194.

- ^ Matot 2013, p. 204.

- ^ Matot 2013, pp. 209-210.

- ^ Handel 1990, p. 242.

- ^ Matot 2013, pp. 214-217.

- ^ Yu 2000, p. 38.

- ^ Olson 1991, pp. 349–350.

- ^ Le Papier Colonial

- ^ Li & Ou 2001.

المصادر

- Anslinger, H.J.; Tompkins, William F. (1953), The Traffic in Narcotics, Funk and Wagnalls, https://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/people/anslinger/traffic/

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 15 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 957.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 15 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 957. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)- Escarra, Jean (1929), Le régime des concessions étrangères en Chine, Académie de droit international

- Gale, Esson M. (1970), "International Relations: The Twentieth Century", China, Ayer Publishing, pp. 200–221, ISBN 0-8369-1987-4

- A. Choveaux, "Situation économique du territoire de Kouang-Tchéou-Wan en 1923". Annales de Géographie, Volume 34, Nr. 187, pp. 74–77, 1925.

- Handel, Michael (1990), Intelligence and Military Operations, United Kingdom: Routledge

- Li, Chuanyi; Ou, Jie (2001), "湛江维多尔天主教堂考察", Study and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture Series (Tsinghua University) 1, http://www.arch.tsinghua.edu.cn/cscmah/congshu-1.htm

- Luong, Hy Van (1992), Revolution in the Village: tradition and transformation in North Vietnam, 1925–1988, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press

- Matot, Bertrand (2013). Fort Bayard. Quand la France vendait son opium. Paris: Éditions François Bourin.

- Olson, James S., ed. (1991), Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press

- Pieragastini, Steven (2017), State and Smuggling in Modern China: The Case of Guangzhouwan/Zhanjiang, Cross-Currents e-Journal (No. 25), https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-25/pieragastini

- Priestly, Herbert Ingram (1967), France Overseas: Study of Modern Imperialism, United Kingdom: Routledge

- Vannière, Antoine (2020), Kouang Tchéou-Wan, colonie clandestine: Un territoire à bail français en Chine du Sud 1898-1946, Indes Savantes

- Xu, Guangqiu (2001), War Wings: The United States and Chinese Military Aviation, 1929–1949, Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-32004-7

- Yu, Patrick Shuk-Siu (2000), A Seventh Child and the Law, Hong Kong, China: Hong Kong University Press

- lettres > par pays > Chine > Kouang-Tcheou-Wan, Le Papier Colonial: la France d'outre-mer et ses anciennes colonies, http://www.lepapiercolonial.com/home.php?cat=310, retrieved on 2007-01-01[dead link] Includes images of letters sent to and from the territory.

وصلات خارجية

- "Compte administratif du budget local du territoire de Kouang-Tchéou-Wan". National Library of France.

- WorldStatesmen - China

- "Historic pictures of Fort Bayard". Archived from the original on أكتوبر 12, 2007. Retrieved نوفمبر 16, 2010.

- Map of French Guangzhouwan

- Map of French Indochina and Guangzhouwan

- Other map about Guangzhouwan and Indochina

- Map of Kwang Tchou Wan

- "French Colonial Zhanjiang"

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Articles containing فرنسية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- مقالات تحتوي نصوصاً باللغة الصينية

- Portal templates with default image

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Articles with dead external links from October 2017

- معاهدات غير متكافئة

- بلدان سابقة في التاريخ الصيني

- العلاقات الصينية الفرنسية

- امتيازات في الصين

- مستعمرات فرنسية سابقة

- تاريخ گوانگدونگ

- تأسيسات 1898 في الصين

- ولايات وأقاليم انحلت في 1945