سنة الأباطرة الخمسة

| الأسر الإمبراطورية الرومانية | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| سنة الأباطرة الخمسة (193م) | ||

| التأريخ | ||

|

193 |

||

|

193 |

||

|

193–194 |

||

|

193–197 |

||

|

193–211 |

||

| التعاقب | ||

|

||

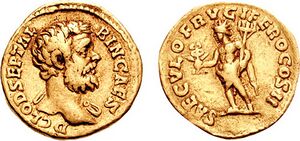

The Year of the Five Emperors was AD 193, in which five men claimed the title of Roman emperor: Pertinax, Didius Julianus, Pescennius Niger, Clodius Albinus, and Septimius Severus. This year started a period of civil war when multiple rulers vied for the chance to become emperor.

The political unrest began with the murder of Emperor Commodus on New Year's Eve 192. Once Commodus was assassinated, Pertinax was named emperor, but immediately aroused opposition in the Praetorian Guard when he attempted to initiate reforms. They then plotted his assassination, and Pertinax was killed while trying to reason with the mutineers.[1] He had only been emperor for three months. Didius Julianus, who purchased the title from the Praetorian Guard, succeeded Pertinax, but was ousted by Septimius Severus and executed on 1 June. Severus was declared Caesar by the Senate, but Pescennius Niger was hostile so he declared himself emperor.[2]

This started the civil war between Niger and Severus; both gathered troops and fought throughout the territory of the empire. Due to this war, Severus allowed Clodius Albinus, whom he suspected of being a threat, to be co-Caesar so that Severus did not have to preoccupy himself with imperial governance. This move allowed him to concentrate on waging the war against Niger.[1] After Severus defeated Niger at the battle of Issus in 194, he turned on Albinus and defeated him at the battle of Lugdunum in 197.

Most historians count Severus and Albinus as two emperors, though they ruled simultaneously. The Severan dynasty was created out of the chaos of AD 193.[2]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ

Fall of Commodus

Commodus' sanity began to unravel after the death of his close associate, Cleander. This triggered a series of summary executions of members of the aristocracy. He began removing himself from his identity as ruler ideologically by resuming his birth name instead of keeping the names that his father gave him when he succeeded to imperial rule. His behavior decayed further as he became more paranoid. He carried out a particularly large massacre in Rome during New Year's Eve AD 192, so that he could become the sole consul. Three nobles, Eclectus, Marcia, and Laetus, fearing that they would be targeted, had Commodus strangled before he could do so. The assassins then named Pertinax the new Caesar.[1]

The identity of the person who planned the murder of Commodus is still a debated topic. Some sources name Pertinax as the mastermind of the assassination because he obtained imperial rule once Commodus was killed. However, the accusations against Pertinax appear to have come from his enemies, an effort to damage his reputation; in reality, these accusers appear not to have known who masterminded the assassination.[1]

پرتيناكس

Pertinax gained his position by rising through the military ranks. He became proconsul of Africa, making him the first of several emperors who began their political careers in Africa.[3] Since most of the nobles had been murdered in the New Year's Eve massacre, Pertinax was one of the few high-ranking officials left to become the new emperor. He faced early difficulties due to the empire's crumbling financial situation and accusations that he was complicit in the assassination of Commodus. He may also have been accused of the murder of Cleander, Commodus' associate, whose murder had triggered Commodus' paranoia.

Pertinax's discipline made a great contrast to Commodus, but he lost the favor of the Praetorian Guard when he refused to pay their donativum and began revoking their privileges under Commodus. When confronted by the Praetorians, he was unable to negotiate a peace and was killed.

Following his death, the Praetorian Guard proceeded to auction off the Purple to the highest bidder.

Didius Julianus

Didius Julianus gained power as proconsul of Africa, succeeding Pertinax in that position. Julianus was not just given the position of emperor after Pertinax's death. He had competition in Pertinax's father-in-law, Sulpicianus, but Julianus outbid him by promising even higher pay for the Praetorian Guard. Julianus was widely suspected of Pertinax's murder. Two public figures used the public's fear to take advantage of this crisis: Pescennius Niger, governor of Syria, and Septimius Severus, who declared himself emperor twelve days after Pertinax's death. The anti-Julianus mobs called on Pescennius Niger for assistance, but Severus, in Pannonia, was closest to Rome. He reached the capital first with his troops and executed Julianus on 1 June, just two months after Pertinax.[1]

Pescennius Niger

Niger began 193 as the governor of Syria. Once the mobs started to clamor for him, he declared himself emperor in rivalry with Severus.[1] With allies in the eastern part of the empire, he gathered an army and fought Severus throughout the empire for two years. He eventually lost the civil war during a battle near the city of Issus in 194.[2]

Clodius Albinus

Clodius Albinus came into contention for the imperial office in 193, when he was asked to become emperor after the death of Commodus, but rejected the proposition. He eventually gained the title of Caesar as a second to Severus, ruling the empire while Severus was on campaign against Niger. Severus and Albinus were considered enemies at the time, but they made a compact or treaty which gave Albinus administrative power and the title of Caesar. Albinus controlled Britain, and the agreement gave him Gaul and Spain. Some sources say that this agreement was fully under the control of Severus, who retained ultimate imperial power.[4] Albinus continued as Caesar for three years before a civil war broke out between the two, resulting in Severus becoming sole emperor after the battle of Lugdunum in 197 in which Albinus was killed.[2]

Septimius Severus

Severus was, practically speaking, the emperor after Pertinax was assassinated. Some sources tie Severus and Pertinax together as allies, which would explain how Severus became so powerful during this chaotic year. He had originally thought to take the throne after Commodus' murder, but was forestalled when the assassins hastily named Pertinax emperor. Twelve days after the 28 March assassination of Pertinax, Severus made himself ruler with the Senate's backing.[1] He had Didius Julianus executed and made enemies of the other powerful nobles who aspired to the throne, Niger and Albinus.

For the first few years of his reign, he was preoccupied with the civil war against Niger in the east, so he allied with Albinus despite their rivalry, granting Albinus the title of Caesar but not the real military power.[4] However, once Severus defeated Niger, he set his sights on Albinus and waged a successful civil war against him.[5] After defeating both enemies, Severus purged their followers to consolidate his position as sole Caesar, founding the Severan dynasty.

See also

- Year of the Four Emperors (AD 69)

- Year of the Six Emperors (AD 238)

References

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Rahman, Abdur (2001). The African Emperor? The Life, Career, and Rise to Power of Septimius Severus, MA thesis. University of Wales Lampeter.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Birley, Arthur R. (1999). Septimius Severus: The African Emperor. New York: Routledge. pp. 89–128. ISBN 0415165911.

- ^ Birley, Arthur R. Septimius Severus: The African Emperor. New York: Routledge, 1999. 89–128.

- ^ أ ب Van Sickle, C.E. (April 1928). "Legal Status of Clodius Albinus, 193–196". Classical Philology. University of Chicago Press. 23 (2): 123–127. doi:10.1086/361015. S2CID 224792179.

- ^ Burckhardt, Jacob. The Age of Constantine the Great. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1949. 19–21.

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- أباطرة رومان

- Civil wars of the Roman Empire

- 2nd-century Roman emperors

- 190s in the Roman Empire

- 192

- 193

- Severan dynasty

- Wars of succession involving the states and peoples of Europe

- Wars of succession involving the states and peoples of Africa

- Wars of succession involving the states and peoples of Asia