جمهورية هرسگ-بوسنا الكرواتية

جمهورية هرسگ-بوسنا الكرواتية Hrvatska Republika Herceg-Bosna | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991–1996 | |||||||||

موقع جمهورية هرسگ-بوسنا الكرواتية (يظهر بالأحمر) ضمن البوسنة والهرسك (تظهر بالوردي) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| الوضع | كيان غير معترف به في البوسنة والهرسك | ||||||||

| العاصمة | موستار | ||||||||

| اللغات المشتركة | الكرواتية | ||||||||

| الحكومة | جمهورية | ||||||||

| الرئيس | |||||||||

• 1991–94 | ماتى بوبان | ||||||||

• 1994–96 | كرشيمير زوباك | ||||||||

| رئيس الوزراء | |||||||||

• 1993–96 | Jadranko Prlić | ||||||||

• 1996 | Pero Marković | ||||||||

| الحقبة التاريخية | الحروب اليوغسلاڤية | ||||||||

• اعلان المجتمع | 18 نوفمبر 1991 | ||||||||

| 6 أبريل 1992 | |||||||||

• أُعلِن أنه غير دستوريa | 14 سبتمبر 1992 | ||||||||

| 18 أكتوبر 1992 | |||||||||

• إعلان الجمهورية | 28 أغسطس 1993 | ||||||||

| 18 مارس 1994 | |||||||||

• أُلغيت رسمياً | 14 أغسطس 1996 | ||||||||

| العملة | رسمياً: دينار البوسنة والهرسك الموازي: مارك ألماني، دينار كرواتي[1] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

جمهورية هرسگ-بوسنا الكرواتية (كرواتية: Hrvatska Republika Herceg-Bosna) كانت كياناً جيوسياسياً غير معترف به و دولة أولية في البوسنة والهرسك. وقد أُعلنت في 18 نوفمبر 1991 تحت اسم المجتمع الكرواتي هرسگ-بوسنا (كرواتية: Hrvatska Zajednica Herceg-Bosna) كـ "كلٍ سياسي وثقافي واقتصادي وأرضي" في أرض البوسنة والهرسك.

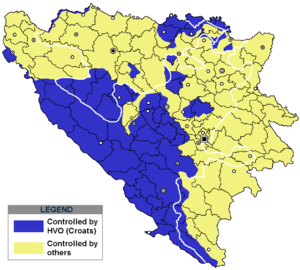

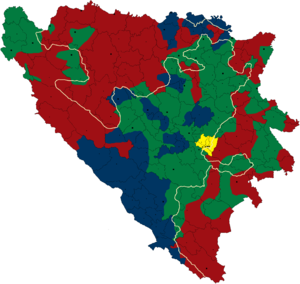

المجتمع الكرواتي پوساڤينا البوسنية، المعلن في شمال البوسنة في 12 نوفمبر 1991، انضم إلى هرسگ-بوسنا في أكتوبر 1992. وفي حدودها المعلـَنة، ضمت هرسگ-بوسنا نحو 30% من البلد،إلا أنها لم تكن مسيطرة فعلياً على كل الأراضي كأجزاء منها التي استولى عليها جيش جمهورية صرب البوسنة (VRS) في بداية حرب البوسنة. القوات المسلحة لهرسگ-بوسنا، مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي (HVO)، تشكلت في 8 أبريل 1992 وقاتلت في البداية في تحالف مع البشناق (المسلمون البوسنيين). تدهورت علاقاتهما في أواخر 1992، مما أدى إلى حرب البشناق والكروات.

المحكمة الدستورية في جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك أعلنت أن هرسگ-بوسنا هي كيان غير دستوري في 14 سبتمبر 1992. اعترفت هرسگ-بوسنا بحكومة جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك وعمل كدولة ضمن الدولة، بينما البعض في قيادتها نادى بانفصال الكيان واتحاده مع كرواتيا.

وفي 28 أغسطس 1993، هرسگ-بوسنا أُعلِنت جمهورية مُتبـِعةً مقترَح خطة أوِن–ستولتنبرگ، الذي ارتآى البوسنة والهرسك كاتحاد من ثلاث جمهوريات. عاصمتها كانت موستار، التي كانت آنذاك منطقة قتال، وكان مركز السيطرة الفعلي قائم في گروده. وفي مارس 1994، وُقـِّعت اتفاقية واشنطن التي أنهت النزاع بين الكروات والبشناق. بمقتضى الاتفاقية، فإن هرسگ-بوسنا انضمت إلى الاتحاد الكرواتي-البشناقي، ولكنها ظلت باقية حتى تم حلها رسمياً في 1996.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

أصل الاسم

التعبير هرسگ-بوسنا (كرواتية: Herceg-Bosna) ظهر في أواخر القرن التاسع عشر واِستُخدِم كمرادف للبوسنة والهرسك بدون مضمون سياسي. وكان يتواجد بكثرة في الأشعار الشعبية كإسم أكثر شاعرية للبوسنة والهرسك. أحد الاستخدامات المبكرة للتعبير كان للكاتب الكرواتي إيڤان زوڤكو في كتابه الصادر في 1899 بعنوان "الهوية الكرواتية في تقاليد وعادات هرسگ-بوسنا". وقد استخدم المؤرخ الكرواتي فردو شيشتش التعبير في كتابه في عام 1908 "هرسگ-بوسنا بمناسبة الضم". في النصف الأول من القرن العشرين، اِستُخدِم الاسم هرسگ-بوسنا من قِبل مؤرخين مثل حمدية كرشيڤلياكوڤتش و دومنيك مانديتش والسياسيين الكروات ڤلادكو ماتشك و ملادن لوركوڤتش. تناقص استخدام التعبير في النصف الثاني من القرن العشرين، حتى 1991 وإعلان المجتمع الكرواتي هرسگ-بوسنا.[2] منذ ع1990، فقد اِستُخدِمت للاشارة إلى الإقليم الكرواني في البوسنة والهرسك.[3]

توقيع اتفاقية واشنطن في مارس 1994 وإنشاء اتحاد البوسنة والهرسك، أحد كانتوناتها سُمي "هرسگ-بوسنا". وفي 1997، أُعلِن أن هذا الاسم غير دستوري، من قِبل المحكمة الدستورية لاتحاد البوسنة والهرسك، وتغير الاسم رسمياً إلى "الكانتون 10".[4]

خلفية

في مطلع 1991، عقب 14th Extraordinary Congress of the الحزب الشيوعي اليوغسلاڤ, the leaders of the six Yugoslav republics began a series of meetings to solve the crisis in يوغوسلاڤيا. The Serbian leadership favored a federal solution، بيما فضّلت القيادتان الكرواتية والسلوڤينية تحالفاً من دول ذات سيادة. علي عزت بگوڤيتش proposed an asymmetrical federation on 22 February, where Slovenia and Croatia would maintain loose ties مع الجمهوريات الأربع الباقية. Shortly after that, he changed his position and opted for a sovereign Bosnia as a prerequisite for such a federation.[5] في 25 مارس 1991، التقى الرئيس الكرواتي فرانيو تودجمان بالرئيس الصربي سلوبودان ميلوشڤتش في Karađorđevo, allegedly to discuss the تقسيم البوسنة والهرسك.[6][7] وفي 6 يونيو، اقترح بگوڤيتش والرئيس المقدوني كيرة گليگوروڤ كونفدرالية ضعيفة بين كرواتيا وسلوڤينيا واتحاد من الجمهوريات الأربع الأخرى، وهو ما رفضه ميلوشڤتش.[8]

في 13 يوليو، اقترحت حكومة هولندا، التي كانت تترأس المجتمع الأوروپي آنذاك، على باقي دول المجتمع الأوروبي أن احتمال تغيير متفق عليه لحدود الجمهوريات اليوغسلاڤية يمكن استكشافه، ولكن المقترح رفضه باقي الأعضاء.[9] وفي يوليو 1991، صاغ رادوڤان كرادزيتش، رئيس جمهورية صرب البوسنة المعلَنة بدون اعتراف دولي، و محمد فيليپوڤتش، نائب رئيس منظمة البشناق المسلمين (MBO)، اتفاقية بين الصرب والبشناق كانت ستضع البوسنة في اتحاد دول مع جمهورية صربيا الاشتراكية و[[جمهورية الجبل الأسود الاشتراكية. الاتحاد الديمقراطي الكرواتي (HDZ BiH) و الحزب الاشتراكي الديمقراطي (SDP BiH) أدانا الاتفاق، واصفين إياه بأنه حلف مضاد للكروات وخيانة. وبالرغم من ترحيبه الأولي بالمبادرة، إلا أن علي عزت بگوڤيتش أيضاً رفض الاتفاق.[10][11]

من يوليو 1991 إلى يناير 1992، أثناء حرب الاستقلال الكرواتية، استخدم الجيش الوطني اليوغسلاڤي والميليشيات الصربية الأراضي البوسنية لشن هجمات على كرواتيا.[12] وساعدت الحكومة الكرواتية في تسليح الكروات والبشناق في البوسنة والهرسك، توقعاً منها بانتشار الحرب هناك.[13][12] وفي أواخر 1991 انضم نحو 20,000 كرواتي في البوسنة والهرسك، معظمهم من منطقة الهرسك، في الحرس الوطني الكرواتي.[14] وأثناء الحرب في كرواتيا، ألقى الرئيس البوسني علي عزت بگوڤيتش إعلاناً متلفزاً بالحياد، قائلاً: "هذه ليست حربنا"، وحكومة سراييڤو لم تتخذ إجراءات دفاعية ضد هجوم محتمل من صرب البوسنة والجيش اليوغسلاڤي.[15] وافق بگوڤيتش على نزع سلاح قوات الدفاع الإقليمي (TO) المتواجدة في البوسنة، وذلك بطلب من الجيش اليوغسلاڤي. إلا أن هذا الأمر عصاه كروات البوسنة والمنظمات البشناقية التي سيطرت على العديد من منشآت وأسلحة الدفاع الإقليمي.[16][17]

التاريخ

التأسيس

In October 1991 the Croat village of Ravno in Herzegovina was attacked and destroyed by Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) forces before turning south towards the besieged Dubrovnik.[18] These were the first Croat casualties in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Izetbegović did not react to the attack on Ravno. The leadership of Bosnia and Herzegovina initially showed willingness to remain in a rump Yugoslavia, but later advocated for a unified Bosnia and Herzegovina.[19]

حرب البوسنة

بين 29 فبراير و 1 مارس 1992 جرى استفتاء استقلال في جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك الاشتراكية.[20] سؤال الاستفتاء كان: "هل تفضـِّل أن تكون البوسنة والهرسك دولة مستقلة ذات سيادة، بمساواة بين المواطنين والأمم، من مسلمين وصرب وكروات وغيرهم ممن يعيشون فيها؟"[21] الاستقلال فضـَّله بقوة الناخبون البشناق وكروات البوسنة، ولكن الاستقتاء قاطعه إلى حد كبير صرب البوسنة. إجمالي إقبال المصوتين كان 63.6%، منهم 99.7% صوتوا لاستقلال البوسنة والهرسك.[22]

اتفاقية واشنطن

On 26 February 1994 talks began in Washington, D.C. between the Bosnian government leaders and Mate Granić, Croatian Minister of Foreign Affairs to discuss the possibilities of a permanent ceasefire and a confederation of Bosniak and Croat regions.[23] By this time the amount of territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina controlled by the HVO had dropped from 20 percent to 10 percent.[24][25] Boban and HVO hardliners were removed from power[26] while "criminal elements" were dismissed from the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH).[27] Under strong American pressure,[26] a provisional agreement on a Croat-Bosniak Federation was reached in Washington on 1 March. On 18 March, at a ceremony hosted by US President Bill Clinton, Bosnian Prime Minister Haris Silajdžić, Croatian Foreign Minister Mate Granić and President of Herzeg-Bosnia Krešimir Zubak signed the ceasefire agreement. The agreement was also signed by Bosnian President Alija Izetbegović and Croatian President Franjo Tuđman. Under this agreement, the combined territory held by the Croat and Bosnian government forces was divided into ten autonomous cantons. It effectively ended the Croat-Bosniak War.[23]

الأعقاب

In November 1995 the Dayton Agreement was signed by presidents of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia that ended the Bosnian war. The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH) was defined as one of the two entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina and comprised 51% of the territory. The Republika Srpska (RS) comprised the other 49%. However, there were problems with its implementation due to different interpretations of the agreement.[28] An Army of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina was to be created by merging units from the ARBiH and the HVO, though this process was largely ineffective.[29] The Federation was divided into 10 cantons. Croats were a majority in three of them and Bosniaks in five. Two cantons were ethnically mixed, and in municipalities that were divided during the war parallel local administrations remained. The return of refugees was to begin in those cantons.[30] The agreement stipulated that Herzeg-Bosnia be abolished within two weeks.[31]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

المساحة والتعداد

The Croatian Communities of Bosnian Posavina and Herzeg-Bosnia within its proclaimed borders in November 1991 extended at about 30% of Bosnia and Herzegovina. According to the 1991 census, in that territory there were 1,238,512 people with ethnicities as follows.[32]

- الكروات – 556,274 (44.91%)

- البشناق – 398,092 (32.14%)

- الصرب – 203,612 (16.44%)

- اليوغسلاڤ – 56,092 (4.53%)

- غيرهم – 24,505 (1.98%)

During the initial negotiations organized by the international community, the Croatian side advocated for a Croat national unit at some 30% of Bosnia and Herzegovina – slightly altered borders of the Croatian Communities, but with Croat enclaves around Žepče, Banja Luka and Prijedor included.[32]

This maximalist approach was done for a better position during negotiations, which would inevitably reduce the excessive demands to an optimal envision of a Croat unit. Based on later statements of Herzeg-Bosnia leading officials, the optimal range of a Croat territorial unit was within the borders of the 1939 Banovina of Croatia, thus excluding Bosniak and Serb majority areas on the outskirts of Herzeg-Bosnia. Those borders would include around 26% of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The ethnic composition of this area in 1991 was:[33]

- الكروات – 514,228 (50.94%)

- البشناق – 291,232 (28.85%)

- الصرب – 141,805 (14.05%)

- اليوغسلاڤ – 44,043 (4.36%)

- غيرهم – 18,191 (1.80%)

العسكر

الثقافة

The Government of Herzeg-Bosnia founded the National Theatre in 1993 in Mostar. From 1994 it had the title of Croatian National Theatre in Mostar and was the first one with the prefix Croatian. The first play performed in this theatre was A Christmas Fable (Božićna bajka) by Mate Matišić. Foundations of a new building were laid in January 1996.[34]

التعليم

الذكرى

منذ 2005، كانت هناك محاولات من الانفصاليين لاستعادة هرسگ-بوسنا بخلق كيان ثالث في البوسنة والهرسك. وقد بدأ ذلك تحت قيادة إيڤو ميرو يوڤتش، إذ قال "أنا لا أقصد لوم صرب البوسنة، ولكن إذا كان لديهم جمهورية صربية، فيجب أن نخلق جمهورية كرواتية وجمهورية بشناقية (مسلمة)". الممثل الكرواتي في الرئاسة البوسنية الاتحادية، Željko Komšić, عارض ذلك، ولكن بعض السياسيين من كروات البوسنة ينادون بتأسيس كيان (كرواتي) ثالث.[35]

في 2009، نادى ميروسلاڤ تودجمان، ابن الزعيم الكرواتي الراحل فرانيو تودجمان بتأسيس كيان كرواتي.[36][37] وقال چوڤتش: "نريد أن نعيش في البوسنة والهرسك حيث يكون الكروات مساوين للشعبين الآخرين حسب الدستور."[38]

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ Cvikl 2008, p. 124.

- ^ Nuić 28 July 2009.

- ^ Herceg-Bosna Archived 2016-08-03 at the Wayback Machine - الموسوعة الكرواتية

- ^ "U-11/97". Archived from the original on April 19, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ramet 2006, p. 386.

- ^ Ramet 2010, p. 263.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 286.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 248.

- ^ Owen 1996, p. 32-34.

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 426.

- ^ Schindler 2007, p. 71.

- ^ أ ب Lukic & Lynch 1996, p. 206.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 243.

- ^ Hockenos 2003, p. 91-2.

- ^ Shrader 2003, p. 25.

- ^ Shrader 2003, p. 33.

- ^ Malcolm 1995, p. 306.

- ^ Marijan 2004, p. 255.

- ^ Krišto 2011, p. 43.

- ^ Nohlen & Stöver 2010, p. 330.

- ^ Velikonja 2003, p. 237.

- ^ Nohlen & Stöver 2010, p. 334.

- ^ أ ب Bethlehem 1997, p. liv.

- ^ Magaš & Žanić 2001, p. 66.

- ^ Hoare 2010, p. 129.

- ^ أ ب Tanner 2001, p. 292.

- ^ Christia 2012, p. 177.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 255.

- ^ Schindler 2007, p. 252.

- ^ Toal & Dahlman 2011, p. 196.

- ^ Gosztonyi 2003, p. 53.

- ^ أ ب Mrduljaš 2009, p. 831.

- ^ Mrduljaš 2009, p. 833-834.

- ^ Komadina 2014, p. 103.

- ^ Staff. "Bosnia: Regionalization proposal on table". B92. Archived from the original on 22 فبراير 2014. Retrieved 27 أبريل 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ [1] Archived 2009-12-08 at the Wayback Machine, dnevniavaz.ba; accessed 28 April 2015.قالب:Hr icon

- ^ [https://web.archive.org/web/20150702070149/http://www.sabahusa.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=137:tuman-qmaliq-doao-u-zenicu-hrvati-u-bih-moraju-dobiti-entitet&catid=9:vjesti Archived 2015-07-02 at the Wayback Machine], sabahusa.com; accessed 28 April 2015 قالب:Hr icon

- ^ [https://web.archive.org/web/20091213204420/http://www.b92.net/eng/news/region-article.php?yyyy=2009&mm=12&dd=09&nav_id=63621 Archived 2009-12-13 at the Wayback Machine] Archived 2009-12-13 at the Wayback Machine, b92.net; accessed 27 April 2015.

المراجع

- الكتب والدوريات

- Anđelić, Ivan (2009). Hrvatska zajednica Herceg-Bosna 1997. - 2009 [Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia 1997 - 2009] (PDF). Mostar: Hrvatska zajednica Herceg Bosna.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - International Monetary Fund (1996). Bosnia and Herzegovina, recent economic developments. International Monetary Fund. ISBN 9781452773773.

- Calic, Marie–Janine (2012). "Ethnic Cleansing and War Crimes, 1991–1995". In Ingrao, Charles; Emmert, Thomas A. (eds.). Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative (2nd ed.). West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. pp. 114–153. ISBN 978-1-55753-617-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995, Volume 1. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN 978-0-16-066472-4.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995, Volume 2. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN 978-0-16-066472-4.

- Central Intelligence Agency, (1993). Combatant Forces in the Former Yugoslavia (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Christia, Fotini (2012). Alliance Formation in Civil Wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-13985-175-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cvikl, Milan Martin (2008). Analysis of the Economic Measures & Developments in the HZ/HR HB Within the Context of the Economic Environment in BiH 1991-1994. Ljubljana: International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dyker, David A.; Vejvoda, Ivan (2014). Yugoslavia and After: A Study in Fragmentation, Despair and Rebirth. New York City: Routledge. ISBN 9781317891352.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goldstein, Ivo (1999). Croatia: A History. London: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-85065-525-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hoare, Marko Attila (2010). "The War of Yugoslav Succession". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–136. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hockenos, Paul (2003). Homeland Calling: Exile Patriotism and the Balkan Wars. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4158-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Klemenčić, Mladen; Pratt, Martin; Schofield, Clive H. (1994). Territorial Proposals for the Settlement of the War in Bosnia-Hercegovina. IBRU. ISBN 9781897643150.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Komadina, Dragan (2014). "A Short history of Croatian theatre in Bosnia and Herzegovina". Croatian Studies Review. Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History. 9: 98–104.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Krišto, Jure (April 2011). "Deconstructing a myth: Franjo Tuđman and Bosnia and Herzegovina". Review of Croatian History. Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History. 6 (1): 37–66.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lukic, Reneo; Lynch, Allen (1996). Europe from the Balkans to the Urals: The Disintegration of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829200-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Magaš, Branka; Žanić, Ivo (2001). The War in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina 1991–1995. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-8201-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Malcolm, Noel (1995). Povijest Bosne: kratki pregled [Bosnia: A Short History]. Erasmus Gilda.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marijan, Davor (2004). "Expert Opinion: On the War Connections of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (1991 – 1995)". Journal of Contemporary History. Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History. 36: 249–289.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mrduljaš, Saša (2009). "Hrvatska politika unutar Bosne i Hercegovine u kontekstu deklarativnog i realnoga opsega Hrvatska zajednice / republike Herceg-Bosne" [Croatian policy in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the context of declarative and real extent of the Croatian Community / Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia]. Journal for General Social Issues (in Croatian). Split, Croatia: Institute of Social Sciences Ivo Pilar. 18: 825–850.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Mulaj, Kledja (2008). Politics of Ethnic Cleansing: Nation-State Building and Provision of Insecurity in Twentieth-Century Balkans. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780739146675.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nohlen, Dieter; Stöver, Philip (2010). Elections in Europe: A Data Handbook. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft Mbh & Co. ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Owen, David (1996). Balkan Odyssey. London: Indigo.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Owen-Jackson, Gwyneth (2015). Political and Social Influences on the Education of Children: Research from Bosnia and Herzegovina. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781317570141.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ramet, Sabrina P. (2010). "Politics in Croatia since 1990". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 258–285. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shrader, Charles R. (2003). The Muslim-Croat Civil War in Central Bosnia: A Military History, 1992–1994. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-261-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tanner, Marcus (2001). Croatia: A Nation Forged in War. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09125-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Toal, Gerard; Dahlman, Carl T. (2011). Bosnia Remade: Ethnic Cleansing and Its Reversal. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973036-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tomas, Mario; Nazor, Ante (October 2013). "Prikaz i analiza borbi na bosanskoposavskom bojištu 1992" [Analysis of the Military Conflict on the Bosnian-Posavina Battlefront in 1992]. Scrinia Slavonica. Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Historical Institute - Department of History of Slavonia, Srijem and Baranja. 13 (1): 277–315. ISSN 1848-9109.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Velikonja, Mitja (2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- مقالات إخبارية

- Nuić, Tihomir (28 July 2009). "Zašto Herceg-Bosna?" [Why Herzeg-Bosnia?]. Ljubuški portal.

- Perlez, Jane (15 August 1996). "Muslim and Croatian Leaders Approve Federation for Bosnia". New York Times.

- مصادر دولية وحكومية ومنظمات أهلية

- "Prosecutor v. Kordić and Čerkez Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 26 February 2001.

- "Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić, Berislav Pušić - Judgement Summary" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 29 May 2013.

- "Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić, Berislav Pušić - Judgement - Volume 1 of 6" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 29 May 2013.

- "Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić, Berislav Pušić - Judgement - Volume 6 of 6" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 29 May 2013.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

وصلات خارجية

- Text of Washington Agreement

- Herzeg Bosnia Canton/County

- War in BiH from Croatian point of view

- Official website

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Articles containing كرواتية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Bosnia and Herzegovina articles missing geocoordinate data

- All articles needing coordinates

- Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia

- حرب البوسنة

- بلدان سابقة غير معترف بها

- Croat communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- History of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- History of the Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Separatism in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 1992 establishments in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 1994 disestablishments in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- دول وأقاليم تأسست في 1992

- States and territories disestablished in 1994