الجسر على نهر كواي (فيلم)

| The Bridge on the River Kwai | |

|---|---|

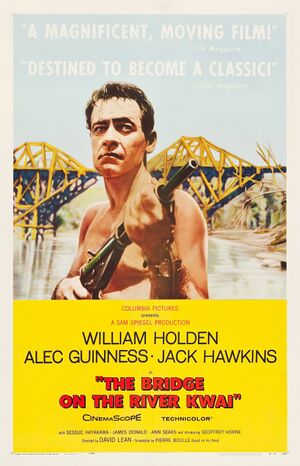

American theatrical release poster, "Style A" | |

| اخراج | David Lean |

| انتاج | Sam Spiegel |

| الحوار السينمائي | |

| بطولة | |

| موسيقى | Malcolm Arnold |

| سينماتوگرافيا | Jack Hildyard |

| تحرير | Peter Taylor |

| شركــة الانتاج | |

| توزيع | Columbia Pictures |

| تواريخ العرض | 2 أكتوبر 1957 (London-premiere) 11 أكتوبر 1957 (United Kingdom)ديسمبر 14، 1957 (United States) |

| طول الفيلم | 161 minutes |

| البلد | United Kingdom United States[1] |

| اللغة | English |

| الميزانية | $2.8 million[2] |

| إيراد الشباك | $30.6 million (worldwide rentals from initial release)[2] |

الجسر على نهر كواي إنگليزية: The Bridge on the River Kwai فيلم سينمائي بريطاني من إخراج داڤيد لين وإنتاج سام سپيگل عام 1957 استنادا إلى رواية كتبها پيير بوليه تحمل نفس العنوان. وكتب السيناريو والحوار كارل فورمان ومايكل ويلسون. وقام بالأدوار الرئيسية ألك گينس وسيزو هاياكاوا ووليام هولدن وجاك هوكنز وجيفري هورن.

تدور أحداث الفيلم أثناء الحرب العالمية الثانية في معسكر ياباني للأسرى من الجيش البريطاني في جنوب بورما حيث يجبر الأسرى على بناء جسر خشبي على نهر كواي لينقل قطارات الجيش الياباني عبره خلال الحرب. ولكنهم بالرغم من عملية التصميم والبناء المتينة إلا أنهم خططوا لتفجيره كونه يخدم أعداءهم اليابانيين.

The Bridge on the River Kwai is widely regarded as one of the greatest films of all time. It was the highest-grossing film of 1957 and received overwhelmingly positive reviews from critics. The film won seven Academy Awards (including Best Picture) at the 30th Academy Awards. In 1997, the film was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the United States Library of Congress.[3][4] It has been included on the American Film Institute's list of best American films ever made.[5][6] In 1999, the British Film Institute voted The Bridge on the River Kwai the 11th greatest British film of the 20th century.

الدقة التاريخية

The plot and characters of Boulle's novel and the screenplay were almost entirely fictional.[7] Since it was not a documentary, there are many historical inaccuracies in the film, as noted by eyewitnesses to the building of the real Burma Railway by historians.[8][9][10][11]

The conditions to which POW and civilian labourers were subjected were far worse than the film depicted.[12] According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission:

The notorious Burma-Siam railway, built by Commonwealth, Dutch and American prisoners of war, was a Japanese project driven by the need for improved communications to support the large Japanese army in Burma. During its construction, approximately 13,000 prisoners of war died and were buried along the railway. An estimated 80,000 to 100,000 civilians also died in the course of the project, chiefly forced labour brought from Malaya and the Dutch East Indies, or conscripted in Siam (Thailand) and Burma. Two labour forces, one based in Siam and the other in Burma, worked from opposite ends of the line towards the centre.[13]

Lieutenant Colonel Philip Toosey of the British Army was the real senior Allied officer at the bridge in question. Toosey was very different from Nicholson and was certainly not a collaborator who felt obliged to work with the Japanese. Toosey in fact did as much as possible to delay the building of the bridge. While Nicholson disapproves of acts of sabotage and other deliberate attempts to delay progress, Toosey encouraged this: termites were collected in large numbers to eat the wooden structures, and the concrete was badly mixed.[9][10] Some consider the film to be an insulting parody of Toosey.[9]

On a BBC Timewatch programme, a former prisoner at the camp states that it is unlikely that a man like the fictional Nicholson could have risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel, and, if he had, due to his collaboration he would have been "quietly eliminated" by the other prisoners.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Julie Summers, in her book The Colonel of Tamarkan, writes that Boulle, who had been a prisoner of war in Thailand, created the fictional Nicholson character as an amalgam of his memories of collaborating French officers.[9] He strongly denied the claim that the book was anti-British, although many involved in the film itself (including Alec Guinness) felt otherwise.[14]

Ernest Gordon, a survivor of the railway construction and POW camps described in the novel/film, stated in his 1962 book, Through the Valley of the Kwai:

In Pierre Boulle's book The Bridge over the River Kwai and the film which was based on it, the impression was given that British officers not only took part in building the bridge willingly, but finished in record time to demonstrate to the enemy their superior efficiency. This was an entertaining story. But I am writing a factual account, and in justice to these men—living and dead—who worked on that bridge, I must make it clear that we never did so willingly. We worked at bayonet point and under bamboo lash, taking any risk to sabotage the operation whenever the opportunity arose.[8]

A 1969 BBC television documentary, Return to the River Kwai, made by former POW John Coast,[11] sought to highlight the real history behind the film (partly through getting ex-POWs to question its factual basis, for example Dr Hugh de Wardener and Lt-Col Alfred Knights), which angered many former POWs. The documentary itself was described by one newspaper reviewer when it was shown on Boxing Day 1974 (The Bridge on the River Kwai had been shown on BBC1 on Christmas Day 1974) as "Following the movie, this is a rerun of the antidote."[15]

Some of the characters in the film use the names of real people who were involved in the Burma Railway. Their roles and characters, however, are fictionalised. For example, a Sergeant-Major Risaburo Saito was in real life second in command at the camp. In the film, a Colonel Saito is camp commandant. In reality, Risaburo Saito was respected by his prisoners for being comparatively merciful and fair towards them. Toosey later defended him in his war crimes trial after the war, and the two became friends.

The major railway bridge described in the novel and film did not actually cross the river known at the time as the Kwai. However, in 1943 a railway bridge was built by Allied POWs over the Mae Klong river – renamed Khwae Yai in the 1960s as a result of the film – at Tha Ma Kham, five kilometres from Kanchanaburi, Thailand.[16] Boulle had never been to the bridge. He knew that the railway ran parallel to the Kwae for many miles, and he therefore assumed that it was the Kwae which it crossed just north of Kanchanaburi. This was an incorrect assumption. The destruction of the bridge as depicted in the film is also entirely fictional. In fact, two bridges were built: a temporary wooden bridge and a permanent steel/concrete bridge a few months later. Both bridges were used for two years, until they were destroyed by Allied bombing. The steel bridge was repaired and is still in use today.[16]

استقبال الفيلم

مبيعات تذاكر المشاهدين

جوائز أوسكار

| الجائزة | الحاصل عليها | |

| أفضل إخراج | داڤيد لين | |

| أفضل ممثل | ألك گينس | |

| أفضل تصوير | جاك هيليارد | |

| أفضل فيلم | سام سپيگل | |

| أفضل مونتاج | پيتر تايلور | |

| أفضل موسيقى | مالكولم أرنولد | |

| أفضل كتابة | كارل فورمان مايكل ويلسون بيير بوليه | |

| الترشيح: | ||

| أفضل ممثل مساند | سيزو هاياكاوا | |

Accolades

American Film Institute lists:

- 1998 — AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies — #13

- 2001 — AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills — #58

- 2006 — AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers — #14

- 2007 — AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) — #36

The film has been selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.

The British Film Institute placed The Bridge on the River Kwai as the 11th greatest British film.

انظر أيضاً

- BFI Top 100 British films

- List of American films of 1957

- List of historical drama films

- List of historical drama films of Asia

- To End All Wars (film)

- Return from the River Kwai (1989 film)

- Siam-Burma Death Railway (film)

مراجع

- ^ "The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 13 يوليو 2012. Retrieved 7 يوليو 2014.

- ^ أ ب Hall, Sheldon (2010). Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History. Wayne State University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0814330081.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 18 سبتمبر 2020.

- ^ "New to the National Film Registry (December 1997) - Library of Congress Information Bulletin". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 18 سبتمبر 2020.

- ^ On the AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies lists, in 1998 (#13) and 2007 (#36)

- ^ Roger Ebert. "Great Movies: The First 100". Retrieved 25 فبراير 2013.

- ^ "Remembering the railway: The Bridge on the River Kwai, www.hellfire-pass.commemoration.gov.au. Retrieved 09-24-2015.

- ^ أ ب Gordon, Ernest (1962). Through the Valley of the Kwai. New York: Harper & Row Publishers. ISBN 978-1579100360.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Summer, Julie (2005). The Colonel of Tamarkan. Simon & Schuster Ltd. ISBN 0-7432-6350-2.

- ^ أ ب Davies, Peter N. (1991). The Man Behind the Bridge. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-485-11402-X.

- ^ أ ب A transcript of the interview and the documentary as a whole can be found in the new edition of John Coast's book Railroad of Death.Coast, John (2014). Railroad of Death. Myrmidon. ISBN 978-1-905802-93-7.

- ^ "links for research, Allied POWs under the Japanese". mansell.com. Retrieved 10 مارس 2016.

- ^ Reading Room Manchester. "CWGC - Cemetery Details". cwgc.org. Retrieved 10 مارس 2016.

- ^ Brownlow, Kevin (1996). David Lean: A Biography. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-14578-0. pp. 391 and 766n

- ^ "Boxing Day [TV Listing]". The Guardian. London. 24 ديسمبر 1974. p. 14.

- ^ أ ب "The Colonel of Tamarkan: Philip Toosey and the Bridge on the River Kwai", published by the National Army Museum on 03-04-2012. Retrieved 09-24-2015.

- Use dmy dates from July 2020

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- أفلام 1957

- أفلام باللغة الإنگليزية

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2021

- Pages with empty portal template

- أفلام إنتاج 1957

- أفلام بريطانية

- أفلام ناطقة بالإنجليزية

- أفلام دراما

- أفلام حروب

- أفلام داڤيد لين

- أفلام ذات إنتاج ضخم

- 1950s war drama films

- 1957 drama films

- 1957 films

- American epic films

- American films

- American war drama films

- American World War II films

- Anti-war films about World War II

- Best British Film BAFTA Award winners

- Best Drama Picture Golden Globe winners

- Best Film BAFTA Award winners

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- British epic films

- British films

- British war drama films

- British World War II films

- Burma Railway

- CinemaScope films

- Columbia Pictures films

- English-language films

- Films about bridges

- Films based on French novels

- Films based on military novels

- Films directed by David Lean

- Films featuring a Best Actor Academy Award-winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Drama Actor Golden Globe winning performance

- Films produced by Sam Spiegel

- Films scored by Malcolm Arnold

- Films set in jungles

- Films set in the 1940s

- Films set in Thailand

- Films shot in Sri Lanka

- Films that won the Best Original Score Academy Award

- Films whose cinematographer won the Best Cinematography Academy Award

- Films whose director won the Best Directing Academy Award

- Films whose director won the Best Director Golden Globe

- Films whose editor won the Best Film Editing Academy Award

- Films whose writer won the Best Adapted Screenplay Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Carl Foreman

- Films with screenplays by Michael Wilson (writer)

- Horizon Pictures films

- Japan in non-Japanese culture

- Pacific War films

- Rail transport films

- United States National Film Registry films

- War epic films

- World War II prisoner of war films