سانتوريني

Santorini / Thera

Σαντορίνη / Θήρα | |

|---|---|

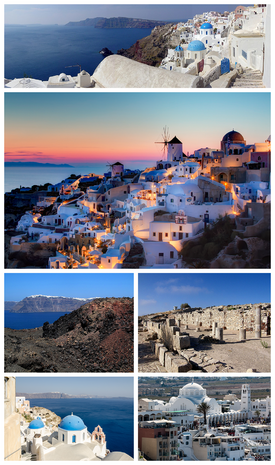

Clockwise from top: Partial panoramic view of Santorini, Sunset in the village of Oia, Ruins of the Stoa Basilica at Ancient Thera, the Orthodox Metropolitan Cathedral of Ypapanti at the town of Fira ([it], the Aegean Sea as seen from Oia, and view of Fira from the island of Nea Kameni at the Santorini caldera. | |

| الإحداثيات: 36°25′N 25°26′E / 36.417°N 25.433°E | |

| البلد | |

| المنطقة الادارية | South Aegean |

| الوحدة المحلية | Thira |

| المساحة | |

| • البلدية | 90٫69 كم² (35٫02 ميل²) |

| التعداد (2011)[1] | |

| • البلدية | 15٬550 |

| • كثافة البلدية | 170/km2 (440/sq mi) |

| • الوحدة البلدية | 14٬005 |

| Community | |

| • التعداد | 1٬857 (2011) |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 847 00, 847 02 |

| مفتاح الهاتف | 22860 |

| Vehicle registration | EM |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www.thira.gr |

Santorini (باليونانية: Σαντορίνη, تـُنطق [sandoˈrini]), classically Thera (الإنگليزية pronunciation /ˈθɪərə/), and officially Thira (Greek: Θήρα [ˈθira]), is an island in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 km (120 mi) southeast of Greece's mainland. It is the largest island of a small, circular archipelago, which bears the same name and is the remnant of a volcanic caldera. It forms the southernmost member of the Cyclades group of islands, with an area of approximately 73 km2 (28 sq mi) and a 2011 census population of 15,550. The municipality of Santorini includes the inhabited islands of Santorini and Therasia and the uninhabited islands of Nea Kameni, Palaia Kameni, Aspronisi, and Christiana. The total land area is 90.623 km2 (34.990 sq mi).[2] Santorini is part of the Thira regional unit.[3]

Santorini is essentially what remains after an enormous volcanic eruption that destroyed the earliest settlements on a formerly single island, and created the current geological caldera. A giant central, rectangular lagoon, which measures about 12 by 7 km (7.5 by 4.3 mi), is surrounded by 300 m (980 ft) high, steep cliffs on three sides.[4] The main island slopes downward to the Aegean Sea. On the fourth side, the lagoon is separated from the sea by another much smaller island called Therasia; the lagoon is connected to the sea in two places, in the northwest and southwest. The depth of the caldera, at 400m, makes it impossible for any but the largest ships to anchor anywhere in the protected bay; there is also a fisherman's harbour at Vlychada, on the southwestern coast. The island's principal port is Athinios. The capital, Fira, clings to the top of the cliff looking down on the lagoon. The volcanic rocks present from the prior eruptions feature olivine, and have a small presence of hornblende.[5]

It is the most active volcanic centre in the South Aegean Volcanic Arc, though what remains today is chiefly a water-filled caldera. The volcanic arc is approximately 500 km (310 mi) long and 20 to 40 km (12 to 25 mi) wide. The region first became volcanically active around 3–4 million years ago[بحاجة لمصدر], though volcanism on Thera began around 2 million years ago with the extrusion of dacitic lavas from vents around the Akrotiri.

The island is the site of one of the largest volcanic eruptions in recorded history: the Minoan eruption (sometimes called the Thera eruption), which occurred some 3,600 years ago at the height of the Minoan civilization.[4] The eruption left a large caldera surrounded by volcanic ash deposits hundreds of metres deep. This may have led indirectly to the collapse of the Minoan civilization on the island of Crete, 110 km (68 mi) to the south, through a gigantic tsunami. Another popular theory holds that the Thera eruption is the source of the legend of Atlantis.[6]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الأسماء

الجيولوجيا

الثوران المينوي

The devastating volcanic eruption of Thera has become the most famous single event in the Aegean before the fall of Troy. It may have been one of the largest volcanic eruptions on Earth in the last few thousand years, with an estimated VEI (volcanic explosivity index) of 6 according to the last studies published in 2006, confirming the prior values. The violent eruption was centred on a small island just north of the existing island of Nea Kameni in the centre of the caldera; the caldera itself was formed several hundred thousand years ago by the collapse of the centre of a circular island, caused by the emptying of the magma chamber during an eruption. It has been filled several times by ignimbrite since then, and the process repeated itself, most recently 21,000 years ago. The northern part of the caldera was refilled by the volcano, then collapsed once more during the Minoan eruption. Before the Minoan eruption, the caldera formed a nearly continuous ring with the only entrance between the tiny island of Aspronisi and Thera; the eruption destroyed the sections of the ring between Aspronisi and Therasia, and between Therasia and Thera, creating two new channels.

On Santorini, a deposit of white tephra thrown from the eruption is found lying up to 60 m (200 ft) thick, overlying the soil marking the ground level before the eruption, and forming a layer divided into three fairly distinct bands indicating different phases of the eruption. Archaeological discoveries in 2006 by a team of international scientists revealed that the Santorini event was much more massive than previously thought; it expelled 61 cubic kilometres (15 cu mi) of magma and rock into the Earth's atmosphere, compared to previous estimates of only 39 cubic kilometres (9.4 cu mi) in 1991,[7][8] producing an estimated 100 cubic kilometres (24 cu mi) of tephra. Only the Mount Tambora volcanic eruption of 1815, the 181 AD eruption of Lake Taupo, and possibly Baekdu Mountain's 969 AD eruption have released more material into the atmosphere during the past 5,000 years.

تخمينات حول العلاقة بالخروج

In The Parting of the Sea: How Volcanoes, Earthquakes, and Plagues Shaped the Exodus Story,[9] geologist Barbara J. Sivertsen seeks to establish a link between the eruption of Santorini (c. 1600 BC) and the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt in the Bible.

A 2006 documentary film by Simcha Jacobovici, The Exodus Decoded,[10] postulates that the eruption of the Santorini Island volcano (referred to as c. 1500 BC) caused all the biblical plagues described against Egypt. The documentary presents this date as corresponding to the time of the Biblical Moses. The film asserts that the Hyksos were the Israelites and that some of them may have originally been from Mycenae. The film also suggests that these original Mycenaean Israelites fled Egypt (which they had in fact ruled for some time) after the eruption, and went back to Mycenae. The Pharaoh of the Exodus is identified with Ahmose I. Rather than crossing the Red Sea, Jacobovici argues a marshy area in northern Egypt known as the Reed Sea would have been alternately drained and flooded by tsunamis caused by the caldera collapse, and could have been crossed during the Exodus.

Jacobovici's assertions in The Exodus Decoded have been extensively criticized by religious and other scholars.[11][12] In a 2013 book on this connection, Thera and the Exodus, a dissident from the consensus Riaan Booysen, tries to support Jacobovici's theory and claims the pharaoh of the Exodus to be Amenhotep III and the biblical Moses as Crown Prince Thutmose, Amenhotep’s first-born son and heir to his throne.[13]

تخمينات حول العلاقة بأطلانطيس

Archaeological, seismological, and vulcanological evidence[14][15][16] has been presented linking the Atlantis myth to Santorini. Speculation suggesting that Thera/Santorini was the inspiration for Plato's Atlantis began with the excavation of Akrotiri in the 1960s, and gained increased currency as reconstructions of the island's pre-eruption shape and landscape frescos located under the ash both strongly resembled Plato's description. The possibility has been more recently popularized by television documentaries such as The History Channel programme Lost Worlds (episode "Atlantis"), the Discovery Channel's Solving History with Olly Steeds, and the BBC's Atlantis, The Evidence, which suggests that Thera is Plato's Atlantis.[17][بحاجة لمصدر غير رئيسي]

النشاط البركاني بعد مينوا

Post-Minoan eruptive activity is concentrated on the Kameni islands, in the centre of the lagoon. They have been formed since the Minoan eruption, and the first of them broke the surface of the sea in 197 BC[18] Nine subaerial eruptions are recorded in the historical record since that time, with the most recent ending in 1950.

In 1707 an undersea volcano breached the sea surface, forming the current centre of activity at Nea Kameni in the centre of the lagoon, and eruptions centred on it continue—the twentieth century saw three such, the last in 1950. Santorini was also struck by a devastating earthquake in 1956. Although the volcano is dormant at the present time, at the current active crater (there are several former craters on Nea Kameni), steam and carbon dioxide are given off.

Small tremors and reports of strange gaseous odours over the course of 2011 and 2012 prompted satellite radar technological analyses and these revealed the source of the symptoms; the magma chamber under the volcano was swelled by a rush of molten rock by 10 to 20 million cubic metres between January 2011 and April 2012, which also caused parts of the island’s surface to rise out of the water by a reported 8 to 14 centimetres.[19] Scientists say that the injection of molten rock was equivalent to 20 years’ worth of regular activity.[19]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

المناخ

| Climate data for سانتوريني (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 14 (57) |

14 (57) |

16 (61) |

18 (64) |

23 (73) |

27 (81) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

26 (79) |

23 (73) |

19 (66) |

15 (59) |

21 (70) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12 (54) |

12 (54) |

14 (57) |

16 (61) |

20 (68) |

24 (75) |

26 (79) |

26 (79) |

24 (75) |

21 (70) |

17 (63) |

13 (55) |

19 (66) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 10 (50) |

10 (50) |

11 (52) |

13 (55) |

17 (63) |

21 (70) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

21 (70) |

18 (64) |

14 (57) |

11 (52) |

16 (61) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 71 (2.8) |

43 (1.7) |

40 (1.6) |

16 (0.6) |

11 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

7 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

11 (0.4) |

38 (1.5) |

59 (2.3) |

75 (3.0) |

371 (14.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 59 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 10 |

| Source: holiday-weather.com[20] | |||||||||||||

التاريخ

أكرتيري المينوية

الفترة القديمة

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Towns and villages

معرض صور

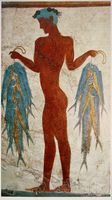

Fresco of "fisherman", Akrotiri

See also

المراجع

الهامش

- ^ أ ب "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in اليونانية). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- ^ "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in اليونانية). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kallikratis law Greece Ministry of Interior (باليونانية)

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةreadersnatural - ^ Michaēl Phytikas, The South Aegean Active Volcanic Arc: Present Knowledge and Future Perspectives

- ^ Charles Pellegrino, Unearthing Atlantis – An Archaeological Odyssey Vintage Books, 1991

- ^ URI.edu, URI Department of Communications and Marketing

- ^ NationalGeographic.com, "Atlantis" Eruption Twice as Big as Previously Believed, Study Suggests.

- ^ Sivertsen, Barbara J (2009). The Parting of the Sea: How Volcanoes, Earthquakes, and Plagues Shaped the Story of the Exodus. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13770-4.

- ^ "The Exodus Decoded Office Website". Theexodusdecoded.net. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

- ^ "Debunking "The Exodus Decoded"". September 20, 2006. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ "The Exodus Decoded: An Extended Review". 19 Dec 2006. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Booysen, Riaan (2013), Thera and the Exodus, O Books, ISBN 978-1-78099-449-9.

- ^ "Santorini Eruption (~1630 BC) and the legend of Atlantis". Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ^ Vergano, Dan (2006-08-27). "Ye gods! Ancient volcano could have blasted Atlantis myth". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ^ Lilley, Harvey (20 April 2007). "The wave that destroyed Atlantis". BBC Timewatch. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ^ Atlantis – The Evidence by Bettany Hughes BBC.co.uk, Timewatch

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةdruitt - ^ أ ب Brian Handwerk (12 September 2012). "Santorini Bulges as Magma Balloons Underneath". National Geographic Society.

- ^ "Weather Averages for Santorini, Greece". holiday-weather.com. Retrieved 2016-09-26.

ببليوگرافيا

- Forsyth, Phyllis Y.: Thera in the Bronze Age, Peter Lang Pub Inc, New York 1997. ISBN 0-8204-4889-3

- Friedrich, W., Fire in the Sea: the Santorini Volcano: Natural History and the Legend of Atlantis, translated by Alexander R. McBirney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000.

- History Channel's "Lost Worlds: Atlantis" archeology series. Features scientists Dr. J. Alexander MacGillivray (archeologist), Dr. Colin F. MacDonald (archaeologist), Professor Floyd McCoy (vulcanologist), Professor Clairy Palyvou (architect), Nahid Humbetli (geologist) and Dr. Gerassimos Papadopoulos (seismologist)

للاستزادة

- Bond, A. and Sparks, R. S. J. (1976). "The Minoan eruption of Santorini, Greece". Journal of the Geological Society of London, Vol. 132, 1–16.

- Doumas, C. (1983). Thera: Pompeii of the ancient Aegean. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Pichler, H. and Friedrich, W.L. (1980). "Mechanism of the Minoan eruption of Santorini". Doumas, C. Papers and Proceedings of the Second International Scientific Congress on Thera and the Aegean World II.

وصلات خارجية

| Find more about Santorini at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| Definitions from Wiktionary | |

| Media from Commons | |

| Quotations from Wikiquote | |

| Source texts from Wikisource | |

| Textbooks from Wikibooks | |

| Travel guide from Wikivoyage | |

| Learning resources from Wikiversity | |

- TheraFoundation.org, The Eruption of Thera: Date and Implications

- Santorini.gr, Thira (Santorini) Municipality Official WebSite

- CGS.Illinois.edu , Was the Bronze Age Volcanic Eruption of Thira (Santorini) a Megacatastrophe? A Geological/Archeological Detective Story, Grant Heiken, Independent consultant, author, geologist (retired) Los Alamos National Laboratory; lecture presented at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, sponsored by CGS.Illinois.edu, Center for Global Studies and CAS.UIUC.edu, Center for Advanced Study

- NewAdvent.org, Thera (Santorin) – Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Volcano.SI.edu: Global Volcanism[dead link]

- URI.edu: Santorini Eruption much larger than previously thought

- Moving Postcards: Santorini

- Older eruption history at Santorini

- Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants and Bang Bang: Santorini In Pop Culture

- The castles of Santorini

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 اليونانية-language sources (el)

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- All pages needing factual verification

- Wikipedia articles needing factual verification from September 2017

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2012

- Articles with dead external links from May 2018

- سانتوريني

- مناطق النبيذ في اليونان

- Supervolcanoes

- Municipalities of the South Aegean

- Landforms of Thira (regional unit)

- Islands of the South Aegean

- Volcanoes of Greece

- VEI-7 volcanoes

- أعضاء العصبة الدلية