تحطيم الأيقونات

تحطيم الأيقونات Iconoclasm[2] هو التدمير المتعمد لـالأيقونات الدينية وغيرها من الرموز أو الآثار، لدوافع دينية أو سياسية. وهو يمثل عنصرًا رئيسيًا متكررًا للتغيرات السياسية أو الدينية البارزة. يشمل المصطلح بشكل أكثر تحديدًا تدمير صورة الحاكم بعد وفاته أو الإطاحة به (الإدانة بعد الموت)، على سبيل المثال، ما حدث بعد وفاة إخناتون (Akhenaten) في مصر القديمة.

يطلق على الأشخاص المشاركين في تحطيم المعتقدات التقليدية أو الداعمين لها "الثائرون ضد العقائد التقليدية"، وهو المصطلح الذي تم تطبيقه بشكل مجازي على الأشخاص الذين يتحدون العقائد أو الاتفاقيات المبرمة. على النقيض من ذلك، يسمى الأشخاص الذين يقدسون أو يبجلون الصور الدينية (بواسطة محطمي الأيقونات) "المؤيدون للمعتقدات التقليدية". في السياق البيزنطي، يعرفون أيضًا باسم "المعتنقين للأيقونية"، أو "iconophiles".[3] Iconoclasm does not generally encompass the destruction of the images of a specific ruler after his or her death or overthrow, a practice better known as damnatio memoriae.

While iconoclasm may be carried out by adherents of a different religion, it is more commonly the result of sectarian disputes between factions of the same religion. The term originates from the Byzantine Iconoclasm, the struggles between proponents and opponents of religious icons in the Byzantine Empire from 726 to 842 AD. Degrees of iconoclasm vary greatly among religions and their branches, but are strongest in religions which oppose idolatry، بما في ذلك الديانات الإبراهيمية.[4] Outside of the religious context, iconoclasm can refer to movements for widespread destruction in symbols of an ideology or cause, such as the destruction of monarchist symbols أثناء الثورة الفرنسية.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

تحطيم الأيقونات الدينية

العصر القديم

In the Bronze Age, the most significant episode of iconoclasm occurred in Egypt during the Amarna Period, when Akhenaten, based in his new capital of Akhetaten, instituted a significant shift in Egyptian artistic styles alongside a campaign of intolerance towards the traditional gods and a new emphasis on a state monolatristic tradition focused on the god Aten, the Sun disk—many temples and monuments were destroyed as a result:[5]

In rebellion against the old religion and the powerful priests of Amun, Akhenaten ordered the eradication of all of Egypt's traditional gods. He sent royal officials to chisel out and destroy every reference to Amun and the names of other deities on tombs, temple walls, and cartouches to instill in the people that the Aten was the one true god.

Public references to Akhenaten were destroyed soon after his death. Comparing the ancient Egyptians with the Israelites, Jan Assmann writes:[6]

For Egypt, the greatest horror was the destruction or abduction of the cult images. In the eyes of the Israelites, the erection of images meant the destruction of divine presence; in the eyes of the Egyptians, this same effect was attained by the destruction of images. In Egypt, iconoclasm was the most terrible religious crime; in Israel, the most terrible religious crime was idolatry. In this respect Osarseph alias Akhenaten, the iconoclast, and the Golden Calf, the paragon of idolatry, correspond to each other inversely, and it is strange that Aaron could so easily avoid the role of the religious criminal. It is more than probable that these traditions evolved under mutual influence. In this respect, Moses and Akhenaten became, after all, closely related.

اليهودية

According to the Hebrew Bible, God instructed the Israelites to "destroy all [the] engraved stones, destroy all [the] molded images, and demolish all [the] high places" of the indigenous Canaanite population as soon as they entered the Promised Land.[7]

In Judaism, King Hezekiah purged Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem and all figures were also destroyed in the Land of Israel, including the Nehushtan, as recorded in the Second Book of Kings. His reforms were reversed in the reign of his son Manasseh.[بحاجة لمصدر]

تحطيم الأيقونات في التاريخ المسيحي

Scattered expressions of opposition to the use of images have been reported: in 305–306 AD, the Synod of Elvira appeared to endorse iconoclasm; Canon 36 states, "Pictures are not to be placed in churches, so that they do not become objects of worship and adoration."[8][9][i] Proscription ceased after the destruction of pagan temples. However, widespread use of Christian iconography only began as Christianity increasingly spread among gentiles after the legalization of Christianity by Roman Emperor Constantine (c. 312 AD). During the process of Christianisation under Constantine, Christian groups destroyed the images and sculptures expressive of the Roman Empire's polytheist state religion.[بحاجة لمصدر]

العصر البيزنطي

قد يقوم بتحطيم المعتقدات التقليدية أشخاص من ديانات مختلفة، ولكنها غالبًا ما تنشأ نتيجة نزاعات طائفية بين فصائل الدين الواحد. في المسيحية، حرض على تحطيم المعتقدات التقليدية الأشخاص الذين يتبنون التفسير الحرفي لـالوصايا العشر، التي تحرم صنع وعبادة "الصور المحفورة أو ما شابه ذلك".[11] اختلفت درجة تحطيم المعتقدات التقليدية بين الطوائف المسيحية إلى حد كبير.

الاصلاح الپروتستانتي

لقد حطمنا نحو مائة صورة مؤمنة بالبدع؛ وسبع رهبان يحتضنون راهبة؛ وصورة الرب والمسيح؛ وصور أخرى مختلفة ذاخرة بالبدع؛ و 200 كانوا قد حـُطـِّموا قبل وصولي. وقد أخذنا بعيداً نقوشاً تتضرع بالدعاء Ora pro nobis ("صلّي لنا") وحطمنا صليباً حجرياً كبيراً أعلى الكنيسة.

— داوسنگ،[12] ص. 15، هاڤرهل، سفوك، 6 يناير 1644

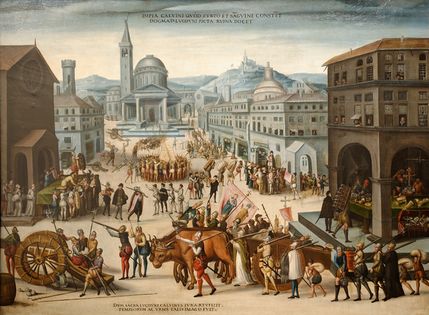

- Calvinist Iconoclasm during the Reformation

16th-century iconoclasm in the Protestant Reformation. Relief statues in St. Stevenskerk in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, were attacked and defaced by Calvinists in the Beeldenstorm.[13][14]

Looting of the Churches of Lyon by the Calvinists in 1562 by Antoine Caron.

Destruction of religious images by the Reformed in Zurich, 1524.

Remains of Calvinist iconoclasm, Clocher Saint-Barthélémy, La Rochelle, France.

تحطيم الأيقونات الإسلامي

Islam has a much stronger tradition of opposing the depictions of figures, especially religious figures,[4] with Sunni Islam being more opposed than Shia Islam. In the history of Islam, the act of removing idols from the Ka'ba in Mecca has great symbolic and historic importance for all believers.

In general, Muslim societies have avoided the depiction of living beings (animals and humans) within such sacred spaces as mosques and madrasahs. This opposition to figural representation is based not on the Qur'an, but on traditions contained within the Hadith. The prohibition of figuration has not always been extended to the secular sphere, and a robust tradition of figural representation exists within Muslim art.[15] However, Western authors have tended to perceive "a long, culturally determined, and unchanging tradition of violent iconoclastic acts" within Islamic society.[15]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Early Islam in Arabia

The first act of Muslim iconoclasm dates to the beginning of Islam, in 630, when the various statues of Arabian deities housed in the Kaaba in Mecca were destroyed. There is a tradition that Muhammad spared a fresco of Mary and Jesus.[16] This act was intended to bring an end to the idolatry which, in the Muslim view, characterized Jahiliyyah.

The destruction of the idols of Mecca did not, however, determine the treatment of other religious communities living under Muslim rule after the expansion of the caliphate. Most Christians under Muslim rule, for example, continued to produce icons and to decorate their churches as they wished. A major exception to this pattern of tolerance in early Islamic history was the "Edict of Yazīd", issued by the Umayyad caliph Yazīd II in 722–723.[17] This edict ordered the destruction of crosses and Christian images within the territory of the caliphate. Researchers have discovered evidence that the order was followed, particularly in present-day Jordan, where archaeological evidence shows the removal of images from the mosaic floors of some, although not all, of the churches that stood at this time. But, Yazīd's iconoclastic policies were not continued by his successors, and Christian communities of the Levant continued to make icons without significant interruption from the sixth century to the ninth.[18]

Egypt

Al-Maqrīzī, writing in the 15th century, attributes the missing nose on the Great Sphinx of Giza to iconoclasm by Muhammad Sa'im al-Dahr, a Sufi Muslim in the mid-1300s. He was reportedly outraged by local Muslims making offerings to the Great Sphinx in the hope of controlling the flood cycle, and he was later executed for vandalism. However, whether this was actually the cause of the missing nose has been debated by historians.[19] Mark Lehner, having performed an archaeological study, concluded that it was broken with instruments at an earlier unknown time between the 3rd and 10th centuries.[20]

Ottoman conquests

Certain conquering Muslim armies have used local temples or houses of worship as mosques. An example is Hagia Sophia in Istanbul (formerly Constantinople), which was converted into a mosque in 1453. Most icons were desecrated and the rest were covered with plaster. In the 1934, It'd decided to use of Hagia Sophia Mosque as a museum,(it was registered as a mosque), and the restoration of the mosaics was undertaken by the American Byzantine Institute beginning in 1932. In July 2020, Hagia Sophia was again converted to a mosque.

Contemporary events

Certain Muslim denominations continue to pursue iconoclastic agendas. There has been much controversy within Islam over the recent and apparently on-going destruction of historic sites by Saudi Arabian authorities, prompted by the fear they could become the subject of "idolatry."[21][22]

A recent act of iconoclasm was the 2001 destruction of the giant Buddhas of Bamyan by the then-Taliban government of Afghanistan.[23] The act generated worldwide protests and was not supported by other Muslim governments and organizations. It was widely perceived in the Western media as a result of the Muslim prohibition against figural decoration. Such an account overlooks "the coexistence between the Buddhas and the Muslim population that marveled at them for over a millennium" before their destruction.[15] The Buddhas had twice in the past been attacked by Nadir Shah and Aurengzeb. According to art historian F. B. Flood, analysis of the Taliban's statements regarding the Buddhas suggest that their destruction was motivated more by political than by theological concerns.[15] Taliban spokespeople have given many different explanations of the motives for the destruction.

During the Tuareg rebellion of 2012, the radical Islamist militia Ansar Dine destroyed various Sufi shrines from the 15th and 16th centuries in the city of Timbuktu, Mali.[24] In 2016, the International Criminal Court (ICC) sentenced Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi, a former member of Ansar Dine, to nine years in prison for this destruction of cultural world heritage. This was the first time that the ICC convicted a person for such a crime.[25]

The short-lived Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant carried out iconoclastic attacks such as the destruction of Shia mosques and shrines. Notable incidents include blowing up the Mosque of the Prophet Yunus (Jonah)[26] and destroying the Shrine to Seth in Mosul.[27]

Iconoclasm in India

In early Medieval India, there were numerous recorded instances of temple desecration by Indian kings against rival Indian kingdoms, which involved conflicts between devotees of different Hindu deities, as well as conflicts between Hindus, Buddhists, and Jains.[28][29][30]

In 642, the Pallava king Narasimhavarman I looted a Ganesha temple in the Chalukyan capital of Vatapi. In c. 692, Chalukya armies invaded northern India where they looted temples of Ganga and Yamuna.

In the 8th century, Bengali troops from the Buddhist Pala Empire desecrated temples of Vishnu Vaikuṇṭha, the state deity of Lalitaditya's kingdom in Kashmir. In the early 9th century, Indian Hindu kings from Kanchipuram and the Pandyan king Srimara Srivallabha looted Buddhist temples in Sri Lanka. In the early 10th century, the Pratihara king Herambapala looted an image from a temple in the Sahi kingdom of Kangra, which was later looted by the Pratihara king Yasovarman.[28][29][30]

During the Muslim conquest of Sindh

Records from the campaign recorded in the Chach Nama record the destruction of temples during the early 8th century when the Umayyad governor of Damascus, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf,[31] mobilized an expedition of 6000 cavalry under Muhammad bin Qasim in 712.

Historian Upendra Thakur records the persecution of Hindus and Buddhists:

Muhammad triumphantly marched into the country, conquering Debal, Sehwan, Nerun, Brahmanadabad, Alor and Multan one after the other in quick succession, and in less than a year and a half, the far-flung Hindu kingdom was crushed ... There was a fearful outbreak of religious bigotry in several places and temples were wantonly desecrated. At Debal, the Nairun and Aror temples were demolished and converted into mosques.[32]

- Iconoclasm during the Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent

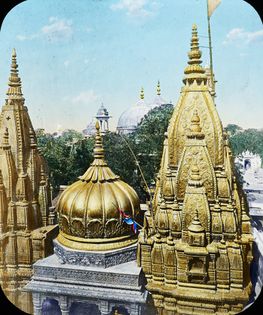

The Somnath Temple in Gujarat was repeatedly destroyed by Islamic armies and rebuilt by Hindus. It was destroyed by Delhi Sultanate's army in 1299 CE.[33] The present temple was reconstructed in Chaulukya style of Hindu temple architecture and completed in May 1951.[34][35]

The Kashi Vishwanath Temple was destroyed by the army of Qutb-ud-din Aibak.

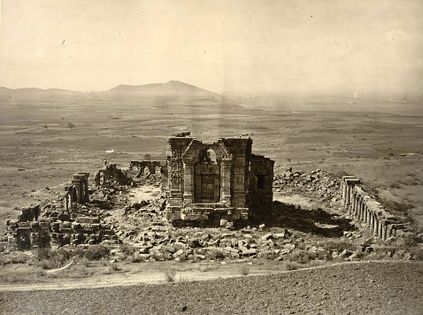

Ruins of the Martand Sun Temple. The temple was destroyed on the orders of Muslim Sultan Sikandar Butshikan in the early 15th century, with demolition lasting a year.

The armies of Delhi Sultanate led by Muslim Commander Malik Kafur plundered the Meenakshi Temple and looted it of its valuables.

Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins; one of the many temple complexes destroyed by the Delhi Sultanate.[36]

Rani ki vav is a stepwell, built by the Chaulukya dynasty, located in Patan; the city was sacked by Sultan of Delhi Qutb-ud-din Aybak between 1200 and 1210, and it was destroyed by the Allauddin Khilji in 1298.[36]

Artistic rendition of the Kirtistambh at Rudra Mahalaya Temple. The temple was destroyed by Alauddin Khalji.

Exterior wall reliefs at Hoysaleswara Temple. The temple was twice sacked and plundered by the Delhi Sultanate.[37]

Chola to Paramara dynasty

In the early 11th century, the Chola king Rajendra I looted temples in a number of neighbouring kingdoms, including:

- Durga and Ganesha temples in the Chalukya Kingdom;

- Bhairava, Bhairavi, and Kali temples in the Kalinga kingdom;

- a Nandi temple in the Eastern Chalukya kingdom; and

- a Siva temple in Pala Bengal.

In the mid-11th century, the Chola king Rajadhiraja plundered a temple in Kalyani. In the late 11th century, the Hindu king Harsha of Kashmir plundered temples as an institutionalised activity. In the late 12th to early 13th centuries, the Paramara dynasty attacked and plundered Jain temples in Gujarat.[28][29][30]

The Somnath temple and Mahmud of Ghazni

Perhaps the most notorious episode of iconoclasm in India was Mahmud of Ghazni's attack on the Somnath temple from across the Thar Desert.[38][39][40] The temple was first raided in 725, when Junayad, the governor of Sind, sent his armies to destroy it.[41] In 1024, during the reign of Bhima I, the prominent Turkic-Muslim ruler Mahmud of Ghazni raided Gujarat, plundering the Somnath temple and breaking its jyotirlinga despite pleas by Brahmins not to break it. He took away a booty of 20 million dinars.[42][40] The attack may have been inspired by the belief that an idol of the goddess Manat had been secretly transferred to the temple.[43] According to the Ghaznavid court-poet Farrukhi Sistani, who claimed to have accompanied Mahmud on his raid, Somnat (as rendered in Persian) was a garbled version of su-manat referring to the goddess Manat. According to him, as well as a later Ghaznavid historian Abu Sa'id Gardezi, the images of the other goddesses were destroyed in Arabia but the one of Manat was secretly sent away to Kathiawar (in modern Gujarat) for safekeeping. Since the idol of Manat was an aniconic image of black stone, it could have been easily confused with a lingam at Somnath. Mahmud is said to have broken the idol and taken away parts of it as loot and placed so that people would walk on it. In his letters to the Caliphate, Mahmud exaggerated the size, wealth and religious significance of the Somnath temple, receiving grandiose titles from the Caliph in return.[42]

The wooden structure was replaced by Kumarapala (r. 1143–72), who rebuilt the temple out of stone.[44]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Mamluk dynasty onward

Historical records compiled by Muslim historian Maulana Hakim Saiyid Abdul Hai attest to the religious violence during the Mamluk dynasty under Qutb-ud-din Aybak. The first mosque built in Delhi, the "Quwwat al-Islam" was built with demolished parts of 20 Hindu and Jain temples.[45][46] This pattern of iconoclasm was common during his reign.[47]

During the Delhi Sultanate, a muslim army led by Malik Kafur, a general of Alauddin Khalji, pursued two violent campaigns into south India, between 1309 and 1311, against three Hindu kingdoms of Deogiri (Maharashtra), Warangal (Telangana) and Madurai (Tamil Nadu). Many Temples were plundered; Hoysaleswara Temple was destroyed.[48][49]

In Kashmir, Sikandar Shah Miri (1389–1413) began expanding, and unleashed religious violence that earned him the name but-shikan, or 'idol-breaker'.[50] He earned this sobriquet because of the sheer scale of desecration and destruction of Hindu and Buddhist temples, shrines, ashrams, hermitages, and other holy places in what is now known as Kashmir and its neighboring territories. Firishta states, "After the emigration of the Bramins, Sikundur ordered all the temples in Kashmeer to be thrown down."[51] He destroyed vast majority of Hindu and Buddhist temples in his reach in Kashmir region (north and northwest India).[52]

In the 1460s, Kapilendra, founder of the Suryavamsi Gajapati dynasty, sacked the Saiva and Vaishnava temples in the Cauvery delta in the course of wars of conquest in the Tamil country. Vijayanagara king Krishnadevaraya looted a Bala Krishna temple in Udayagiri in 1514, and looted a Vittala temple in Pandharpur in 1520.[28][29][30]

A regional tradition, along with the Hindu text Madala Panji, states that Kalapahad attacked and damaged the Konark Sun Temple in 1568.[53][54]

Some of the most dramatic cases of iconoclasm by Muslims are found in parts of India where Hindu and Buddhist temples were razed and mosques erected in their place. Aurangzeb, the 6th Mughal Emperor, destroyed the famous Hindu temples at Varanasi and Mathura.[55]

In modern India, the most high-profile case of iconoclasm was from 1992. Hindus, led by the Vishva Hindu Parishad and Bajrang Dal, destroyed the 430-year-old Islamic Janmasthan Mosque in Ayodhya that was built in 1528 by demolishing a Rama temple.[56][57]

Iconoclasm in East Asia

China

There have been a number of anti-Buddhist campaigns in Chinese history that led to the destruction of Buddhist temples and images. One of the most notable of these campaigns was the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution of the Tang dynasty.

During and after the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, there was widespread destruction of religious and secular images in China.

During the Northern Expedition in Guangxi in 1926, Kuomintang General Bai Chongxi led his troops in destroying Buddhist temples and smashing Buddhist images, turning the temples into schools and Kuomintang party headquarters.[58] It was reported that almost all of the viharas in Guangxi were destroyed and the monks were removed.[59] Bai also led a wave of anti-foreignism in Guangxi, attacking Americans, Europeans, and other foreigners, and generally making the province unsafe for foreigners and missionaries. Westerners fled from the province and some Chinese Christians were also attacked as imperialist agents.[60] The three goals of the movement were anti-foreignism, anti-imperialism and anti-religion. Bai led the anti-religious movement against superstition. Huang Shaohong, also a Kuomintang member of the New Guangxi clique, supported Bai's campaign. The anti-religious campaign was agreed upon by all Guangxi Kuomintang members.[61]

There was extensive destruction of religious and secular imagery in Tibet after it was invaded and occupied by China.[62]

Many religious and secular images were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976, ostensibly because they were a holdover from China's traditional past (which the Communist regime led by Mao Zedong reviled). The Cultural Revolution included widespread destruction of historic artworks in public places and private collections, whether religious or secular. Objects in state museums were mostly left intact.

Other examples

Other examples of political destruction of images include:

- There have been several cases of removing symbols of past rulers in Malta's history. Many Hospitaller coats of arms on buildings were defaced during the French occupation of Malta in 1798–1800; a few of these were subsequently replaced by British coats of arms in the early 19th century.[63] Some British symbols were also removed by the government after Malta became a republic in 1974. These include royal cyphers being ground off from post boxes,[64] and British coats of arms such as that on the Main Guard building being temporarily obscured (but not destroyed).[65]

- With the entry of the Ottoman Empire to the First World War, the Ottoman Army destroyed the Russian victory monument erected in San Stefano (the modern Yeşilköy quarter of Istanbul) to commemorate the Russian victory in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. The demolition was filmed by former army officer Fuat Uzkınay, producing Ayastefanos'taki Rus Abidesinin Yıkılışı—the oldest known Turkish-made film.

- In the late 18th century, the Brabant Revolutionaries sacked Brussels' Grand Place, destroying statues of nobility and symbols of Christianity.[66] In the 19th Century, the place was renovated and many new statues added. In 1911, a marble commemoration for the Spanish freethinker and educator Francisco Ferrer, executed two years earlier and widely considered a martyr, was erected in the Grand Place. The statue depicted a nude man holding the Torch of Enlightenment. The Imperial German military, which occupied Belgium during the First World War, disliked the monument and destroyed it in 1915. It was restored in 1926 by the International Free Thought Movement.[67]

- In 1942 the pro-Nazi Vichy Government of France took down and melted Clothilde Roch's statue of the 16th-century dissident intellectual Michael Servetus, who had been burned at the stake in Geneva at the instigation of Calvin. The Vichy authorities disliked the statue, as it was a celebration of freedom of conscience. In 1960, having found the original molds, the municipality of Annemasse had it recast and returned the statue to its previous place.[68]

- The Battle of Baghdad symbolically ended with the Firdos Square statue destruction, a U.S. military-staged event in April 2003 where a prominent statue of Saddam Hussein was pulled down.

- In 2016, paintings from the University of Cape Town were burned in student protests as symbols of colonialism.[69]

- In November 2019 the statue of Swedish footballer Zlatan Ibrahimović was vandalized by Malmö FF supporters after he announced he had become part-owner of Swedish rivals Hammarby. White paint was sprayed on it; threats and hateful messages towards Zlatan were written on the statue, and it was burned.[70][71] In a second attack the nose was sawed off and the statue was sprinkled with chrome paint.[72] On 5 January 2020 it was finally toppled.[73]

- In June 2020 the governing body of Oriel College at the University of Oxford voted to remove a statue of Cecil Rhodes, which was the target of the Rhodes Must Fall movement[74].

In the Soviet Union

During and after the October Revolution, widespread destruction of religious and secular imagery in Russia took place, as well as the destruction of imagery related to the Imperial family. The Revolution was accompanied by destruction of monuments of tsars, as well as the destruction of imperial eagles at various locations throughout Russia. According to Christopher Wharton:[75]

In front of a Moscow cathedral, crowds cheered as the enormous statue of Tsar Alexander III was bound with ropes and gradually beaten to the ground. After a considerable amount of time, the statue was decapitated and its remaining parts were broken into rubble.

The Soviet Union actively destroyed religious sites, including Russian Orthodox churches and Jewish cemeteries, in order to discourage religious practice and curb the activities of religious groups.

During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and during the Revolutions of 1989, protesters often attacked and took down sculptures and images of Joseph Stalin, such as the Stalin Monument in Budapest.[76]

انظر أيضًا

الملاحظات

- ^ A possible translation is also: "There shall be no pictures in the church, lest what is worshipped and adored should be depicted on the walls."[بحاجة لمصدر]

المراجع والملاحظات

- ^ Aston 1993; Loach 1999, p. 187; Hearn 1995, pp. 75–76

- ^ Literally, "image-breaking", from باليونانية قديمة: [[[wikt:εἰκών|εἰκών]] و κλάω] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). Iconoclasm may be also considered as a back-formation from iconoclast (من اليونانية εἰκοκλάστης). الكلمة اليونانية المناظرة لتحطيم الأيقونات هي εἰκονοκλασία – eikonoklasia.

- ^ "icono-, comb. form". OED Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ أ ب Crone, Patricia. 2005. "Islam, Judeo-Christianity and Byzantine Iconoclasm." Pp. 59–96 in From Kavād to al-Ghazālī: Religion, Law and Political Thought in the Near East, c. 600-1100, (Variorum). Ashgate Publishing.

- ^ "Akhenaten." Encyclopedia of World Biography. 20 June 2020. via Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Assmann, Jan. 2014. From Akhenaten to Moses: Ancient Egypt and Religious Change. American University in Cairo Press, ISBN 977-416-631-0. p. 76.

- ^ Numbers 33:52 and similarly Deuteronomy 7:5

- ^ Elvira canons, Cua, http://faculty.cua.edu/pennington/canon%20Law/ElviraCanons.htm, "Placuit picturas in ecclesia esse non debere, ne quod colitur et adoratur in parietibus depingatur".

- ^ The Catholic Encyclopedia, "This canon has often been urged against the veneration of images as practised in the Catholic Church. Binterim, De Rossi, and Hefele interpret this prohibition as directed against the use of images in overground churches only, lest the pagans should caricature sacred scenes and ideas; Von Funk, Termel, and Henri Leclercq opine that the council did not pronounce as to the liceity or non-liceity of the use of images, but as an administrative measure simply forbade them, lest new and weak converts from paganism should incur thereby any danger of relapse into idolatry, or be scandalized by certain superstitious excesses in no way approved by the ecclesiastical authority."

- ^ "Byzantine iconoclasm". Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ "You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. 5 You shall not bow down to them or serve them. . . ." (Exodus 20:4-5a, ESV.)

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةDowsing - ^ Stark, Rodney (18 December 2007). The Victory of Reason: How Christianity Led to Freedom, Capitalism, and Western Success (in English). Random House Publishing Group. p. 176. ISBN 9781588365002.

The Beeldenstorm, or Iconoclastic Fury, involved roving bands of radical Calvinists who were utterly opposed to all religious images and decorations in churches and who acted on their beliefs by storming into Catholic churches and destroying all artwork and finery.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Byfield, Ted (2002). A Century of Giants, A.D. 1500 to 1600: In an Age of Spiritual Genius, Western Christendom Shatters (in English). Christian History Project. p. 297. ISBN 9780968987391.

Devoutly Catholic but opposed to Inquisition tactics, they backed William of Orange in subduing the Calvinist uprising of the Dutch beeldenstorm on behalf of regent Margaret of Parma, and had come willingly to the council at her invitation.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث Flood, Finbarr Barry (2002). "Between cult and culture: Bamiyan, Islamic iconoclasm, and the museum". The Art Bulletin. 84 (4): 641–659. doi:10.2307/3177288. JSTOR 3177288.

- ^ Guillaume, Alfred (1955). The Life of Muhammad. A translation of Ishaq's "Sirat Rasul Allah". Oxford University Press. p. 552. ISBN 978-0-19-636033-1. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

Quraysh had put pictures in the Ka'ba including two of Jesus son of Mary and Mary (on both of whom be peace!). ... The apostle ordered that the pictures should be erased except those of Jesus and Mary.

- ^ A. Grabar, L'iconoclasme byzantin: le dossier archéologique (Paris, 1984), 155–56.

- ^ King, G. R. D. (1985). "Islam, iconoclasm, and the declaration of doctrine". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 48 (2): 276–7. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00033346.

- ^ "What happened to the Sphinx's nose?". Smithsonian Journeys. Smithsonian Institution. December 8, 2009.

- ^ Zivie-Coche, Christiane (April 10, 2004). "Sphinx : history of a monument". Ithaca : Cornell University Press – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Howden, Daniel (أغسطس 6, 2005). "Independent Newspaper on-line, London, Jan 19, 2007". News.independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on سبتمبر 8, 2008. Retrieved أبريل 30, 2013.

- ^ "Islamica Magazine". Archived from the original on July 23, 2008.

- ^ "Afghan Taliban leader orders destruction of ancient statues". Rawa.org. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ Tharoor, Ishaan (2012-07-02). "Timbuktu's Destruction: Why Islamists Are Wrecking Mali's Cultural Heritage". TIME. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ "Nine Years for the Cultural Destruction of Timbuktu". The Atlantic. 2016-09-27. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ "Iraq jihadists blow up 'Jonah's tomb' in Mosul". The Telegraph. Agence France-Presse. 25 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ "ISIS destroys Prophet Sheth shrine in Mosul". Al Arabiya News. 26 July 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Eaton, Richard M. (December 2000). "Temple desecration in pre-modern India". Frontline. Vol. 17, no. 25. The Hindu Group.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Eaton, Richard M. (September 2000). "Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States". Journal of Islamic Studies. 11 (3): 283–319. doi:10.1093/jis/11.3.283.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Eaton, Richard M. (2004). Temple desecration and Muslim states in medieval India. Gurgaon: Hope India Publications. ISBN 978-8178710273.

- ^ Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg: The Chachnamah, An Ancient History of Sind, Giving the Hindu period down to the Arab Conquest. [1] Archived 2017-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sindhi Culture by U. T. Thakkur, Univ. of Bombay Publications, 1959.

- ^ Eaton (2000), Temple desecration in pre-modern India Frontline, p. 73, item 16 of the Table, Archived by Columbia University

- ^ Gopal, Ram (1994). Hindu culture during and after Muslim rule: survival and subsequent challenges. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 148. ISBN 81-85880-26-3.

- ^ Jaffrelot, Christophe (1996). The Hindu nationalist movement and Indian politics: 1925 to the 1990s. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 84. ISBN 1-85065-170-1.

- ^ أ ب Richard Eaton (2000), Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States, Journal of Islamic Studies, 11(3), pp 283-319

- ^ Robert Bradnock; Roma Bradnock (2000). India Handbook. McGraw-Hill. p. 959. ISBN 978-0-658-01151-1.

- ^ "Gujarat State Portal | All About Gujarat | Gujarat Tourism | Religious Places | Somnath Temple". Gujaratindia.com. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ Thapar, Romila (April 10, 2005). Somanatha: The Many Voices of a History. Verso. ISBN 9781844670208 – via Google Books.

- ^ أ ب Yagnik, Achyut, and Suchitra Sheth. 2005. Shaping of Modern Gujarat. Penguin UK. ISBN 8184751850.

- ^ "Leaves from the past". Archived from the original on 2007-01-10.

- ^ أ ب Thapar, Romila. 2004. Somanatha: The Many Voices of a History. Penguin Books India. ISBN 1-84467-020-1.

- ^ Akbar, M. J. 2003. The Shade of Swords: Jihad and the Conflict between Islam and Christianity. Roli Books. ISBN 9789351940944.

- ^ Somnath Temple, British Library.

- ^ "Qutb Minar and its Monuments, Delhi". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ^ Welch, Anthony, and Howard Crane. 1983. "The Tughluqs: Master Builders of the Delhi Sultanate." Muqarnas 1:123–66. JSTOR 1523075: The Quwwatu'l-Islam was built with the remains of demolished Hindu and Jain temples.

- ^ "index_1200_1299". www.columbia.edu.

- ^ Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund, A History of India, 3rd Edition, Routledge, 1998, ISBN 0-415-15482-0, pp. 160–161

- ^ Roshen Dalal (2002). The Puffin History of India for Children, 3000 BC - AD 1947. Penguin Books. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-14-333544-3.

- ^ Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor. E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936, Volume 4. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-097902. p. 793

- ^ Firishta, Muhammad Qāsim Hindū Shāh (1981) [1829]. Tārīkh-i-Firishta [History of the Rise of the Mahomedan Power in India]. Translated by John Briggs. New Delhi.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Elliot and Dowson. "The Muhammadan Period." Pp. pp. 457–59 in The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians, Vol. 6. London: Trubner & Co. p. 457.

- ^ Donaldson, Thomas. 2005. Konark. Oxford University Press. pp. 26–28. ISBN 978-0-19-567591-7.

- ^ Behera, Mahendra Narayan. 2003. Brownstudy on Heathenland: A Book on Indology. University Press of America. pp. 146–47. ISBN 978-0-7618-2652-1.

- ^ Pauwels, Heidi; Bachrach, Emilia (2018). "Aurangzeb as Iconoclast? Vaishnava Accounts of the Krishna images' Exodus from Braj". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (in English). 28 (3): 485–508. doi:10.1017/S1356186318000019. ISSN 1356-1863.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "The Context of Anti-Christian Violence". Hrw.org. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ Tully, Mark (5 December 2002). "Tearing down the Babri Masjid". BBC News. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925–1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-521-20204-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Don Alvin Pittman (2001). Toward a modern Chinese Buddhism: Taixu's reforms. University of Hawaii Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-8248-2231-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925–1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-521-20204-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925–1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-521-20204-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Karan, P. P. (2015). "Suppression of Tibetan Religious Heritage". The Changing World Religion Map (in الإنجليزية). Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 461–476. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9376-6_23. ISBN 9789401793759.

- ^ Ellul, Michael (1982). "Art and Architecture in Malta in the Early Nineteenth Century" (PDF). Melitensia Historica. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2016.

- ^ Westcott, Kathryn (18 January 2013). "Letter boxes: The red heart of the British streetscape". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 November 2016.

- ^ Bonello, Giovanni (14 January 2018). "Mysteries of the Main Guard inscription". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018.

- ^ "La Grande-Place de Bruxelles" (in الفرنسية). bruNET. May 17, 2007. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ Avrich, Paul (1980). "The Martyrdom of Ferrer". The Modern School Movement: Anarchism and Education in the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 3–33. ISBN 978-0-691-04669-3. OCLC 489692159, p.33.

- ^ Goldstone, Nancy Bazelon; Goldstone, Lawrence (2003). Out of the Flames: The Remarkable Story of a Fearless Scholar, a Fatal Heresy, and One of the Rarest Books in the World. New York: Broadway. ISBN 978-0-7679-0837-5.pp. 313-316

- ^ Meintjies, Ilze-Marie (16 February 2016). "Protesting UCT Students Burn Historic Paintings, Refuse To Leave". Eyewitness News.

- ^ "Zlatan Ibrahimovic statue: Vandals try to saw through feet". 12 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019 – via BBC News.

- ^ Daniels, Tim. "Zlatan Ibrahimovic's Malmo Statue Set on Fire After Becoming Hammarby Part Owner". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ Erberth, Nellie (December 22, 2019). "Zlatans staty vandaliserad igen – näsan avsågad" – via www.svt.se.

- ^ Wikén, Johan; Erberth, Nellie (January 5, 2020). "Zlatanstatyn vandaliserad igen – avsågad vid fötterna" – via www.svt.se.

- ^ Coughlan, Sean (16 June 2020). "Oxford college wants to remove Cecil Rhodes statue". BBC News Online.

- ^ Christopher Wharton, "The Hammer and Sickle: The Role of Symbolism and Rituals in the Russian Revolution" Archived 2010-05-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Auyezov, Olzhas (January 5, 2011). "Ukraine says blowing up Stalin statue was terrorism". Reuters. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

كتابات أخرى

- Barasch, Moshe (1992). Icon: Studies in the History of an Idea. University of New York Press. ISBN 0-8147-1172-3.

- Besançon, Alain (2009). The Forbidden Image: An Intellectual History of Iconoclasm. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-04414-9.

- Bevan, Robert (2006). The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-319-2.

- Freedberg, David (1977). The Structure of Byzantine and European Iconoclasm (PDF). University of Birmingham, Centre for Byzantine Studies. pp. 165–177. ISBN 978-0-7044-0226-3.

{{cite book}}: Text "in: A. Bryer and J. Herrin, eds., Iconoclasm" ignored (help) - Freedberg, David (1985; reprinted in Public, Toronto, 1993). Iconoclasts and their Motives (Second Horst Gerson Memorial Lecture, University of Groningen) (PDF). Maarssen: Gary Schwartz. ISBN 978-90-6179-056-3.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Gamboni, Dario (1997). The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-316-1.

- Gwynn, David M. From Iconoclasm to Arianism: The Construction of Christian Tradition in the Iconoclast Controversy [Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 47 (2007) 225–251.

- Ivanovic, Filip (2010). Symbol and Icon: Dionysius the Areopagite and the Iconoclastic Crisis. Pickwick. ISBN 978-1-60899-335-2.

- Lambourne, Nicola (2001). War Damage in Western Europe: The Destruction of Historic Monuments During the Second World War. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1285-8.

- Teodoro lo Studita, Antirrheticus Adversus Iconomachos. Confutazioni contro gli avversari delle sante icone, a cura di Antonio Calisi, Chàrisma Edizioni, Bari 2013, pp. 106. ISBN 978-88-908559-0-0

وصلات خارجية

- Iconclasm in England, Holy Cross College

- Design as Social Agent at the ICA by Kerry Skemp, April 5, 2009

- Lang and lang-xx template errors

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2019

- CS1 errors: unrecognized parameter

- Iconoclasm

- تحطيم الأيقونات البيزنطي

- Aniconism

- الأرثوذكسية الشرقية

- إصلاح بروتستانتي

- اضطهاد ديني

- عبارات مسيحية

![16th-century iconoclasm in the Protestant Reformation. Relief statues in St. Stevenskerk in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, were attacked and defaced by Calvinists in the Beeldenstorm.[13][14]](/w/images/thumb/9/90/2008-09_Nijmegen_st_stevens_beeldenstorm.JPG/441px-2008-09_Nijmegen_st_stevens_beeldenstorm.JPG)

![The Somnath Temple in Gujarat was repeatedly destroyed by Islamic armies and rebuilt by Hindus. It was destroyed by Delhi Sultanate's army in 1299 CE.[33] The present temple was reconstructed in Chaulukya style of Hindu temple architecture and completed in May 1951.[34][35]](/w/images/thumb/f/f2/Somnath_temple_ruins_%281869%29.jpg/420px-Somnath_temple_ruins_%281869%29.jpg)

![Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins; one of the many temple complexes destroyed by the Delhi Sultanate.[36]](/w/images/thumb/3/31/Warangal_fort.jpg/196px-Warangal_fort.jpg)

![Rani ki vav is a stepwell, built by the Chaulukya dynasty, located in Patan; the city was sacked by Sultan of Delhi Qutb-ud-din Aybak between 1200 and 1210, and it was destroyed by the Allauddin Khilji in 1298.[36]](/w/images/thumb/1/14/Rani_ki_vav1.jpg/402px-Rani_ki_vav1.jpg)

![Exterior wall reliefs at Hoysaleswara Temple. The temple was twice sacked and plundered by the Delhi Sultanate.[37]](/w/images/thumb/0/0e/Exteriors_Carvings_of_Shantaleshwara_Shrine_02.jpg/562px-Exteriors_Carvings_of_Shantaleshwara_Shrine_02.jpg)