عبادة الأصنام

الصنم أو الوثن هو تمثال أو رمز لإنسان أو جني أو ملاك، يصنعه الإنسان ليعبده ويتخذه إلهاً، ويتقرب إليه بالتذلل والخضوع ما صنعه الإنسان وعبدهُ لأجل التقرب إلى الله.

وقد فرق بعض العلماء بين الصنم والوثن فقالوا: إن الوثن هو ما صنع من الحجارة، والصنم ما صنع من مواد أخرى كالخشب أو الذهب أو الفضة أو غيرها من الجواهر، وقال البعض : إن الصنم ما كان له صورة أما الوثن فهو مالا صورة له.

تاريخ الأصنام

للأصنام عمق تاريخي بعيد، مع الاعتراف بأن التوحيد الذي عبادة الله هو السابق، فعبادة الأصنام حصلت في التاريخ البشري نتيجة الفراغ المعرفي، ونتيجة الغريزة التي في نفس الإنسان في حبه للتدين.

ويجب أن نأخذ بالحسبان أن ما كل تمثال في الحضارات الإنسانية القديمة يعد صنماً، لأنه مجرد تمثال لحاكم أو عظيم لم تكن تصرف عبادة، فالتمثال أو الرمز لا يطلق عليه كلمة صنم إلا إذا عبد.

أصنام العرب

وضع ابن السائب الكلبي كتاباً في أصنام العرب سماه بكتاب الأصنام. ومن الأصنام التي عبدت قبل الإسلام اللات والعزى وهبل وود سواع ويعوق ويغوث ونسر.

الأصنام في الأديان

في الإسلام واليهودية والنصرانية لا تجوز عبادة الأصنام ، ومن يعبدها يكون مشركاً بالله ، والشرك أغلظ من الكفر.

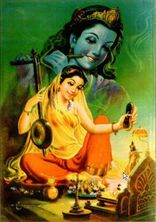

الهندوسية

In Hinduism, an icon, image or statue is called Murti or Pratima.[1][2] Major Hindu traditions such as Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Shaktism and Smartaism favor the use of Murti (idol). These traditions suggest that it is easier to dedicate time and focus on spirituality through anthropomorphic or non-anthropomorphic icons. The Bhagavad Gita – a Hindu scripture, in verse 12.5, states that only a few have the time and mind to ponder and fix on the unmanifested Absolute (abstract formless Brahman), and it is much easier to focus on qualities, virtues, aspects of a manifested representation of god, through one's senses, emotions and heart, because the way human beings naturally are.[3][4]

A murti in Hinduism, states Jeaneane Fowler – a professor of Religious Studies specializing on Indian Religions, is itself not god, it is an "image of god" and thus a symbol and representation.[1] A Murti is a form and manifestation, states Fowler, of the formless Absolute.[1] Thus a literal translation of Murti as idol is incorrect, when idol is understood as superstitious end in itself. Just like the photograph of a person is not the real person, a Murti is an image in Hinduism but not the real thing, but in both cases the image reminds of something of emotional and real value to the viewer.[1] When a person worships a Murti, it is assumed to be a manifestation of the essence or spirit of the deity, the worshipper's spiritual ideas and needs are meditated through it, yet the idea of ultimate reality – called Brahman in Hinduism – is not confined in it.[1]

Devotional (bhakti movement) practices centered on cultivating a deep and personal bond of love with God, often expressed and facilitated with one or more Murti, and includes individual or community hymns, japa or singing (bhajan, kirtan or aarti). Acts of devotion, in major temples particularly, are structured on treating the Murti as the manifestation of a revered guest,[5] and the daily routine can include awakening the murti in the morning and making sure that it "is washed, dressed, and garlanded."[6][7][note 1]

معرض صور

The Ten Commandments on a monument on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol. The first commandment listed is interpreted as prohibiting idolatry, but the nature of the meaning of idolatry in the Biblical law in Christianity is disputed.

Bronze snake (formerly believed to be the one set up by Moses), in the main nave of Sant'Ambrogio basilica in Milan, Italy, a gift from Byzantine emperor Basil II (1007). It stands on an Ancient Roman granite pillar. Picture by Giovanni Dall'Orto, 25 April 2007.

See also

- Bibliolatry

- Buddhist devotion – prayer ritual in Buddhism

- Dambana

- Deity

- El Tío

- Fetishism

- Perceptions of religious imagery in natural phenomena

- Puja (Hinduism) – prayer ritual in Hinduism

Notes

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةnote1

References

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةfowler41 - ^ "pratima (Hinduism)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ Brant Cortright (2010). Integral Psychology: Yoga, Growth, and Opening the Heart. State University of New York Press. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-0-7914-8013-7.

- ^ "Bhagavad-Gita: Chapter 12, Verse 5".

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةGale Encyclopedia of Religion - ^ Klaus Klostermaier (2007) Hinduism: A Beginner's Guide, 2nd Edition, Oxford: OneWorld Publications, ISBN 978-1-85168-163-1, pages 63–65

- ^ Fuller, C. J. (2004), The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 67–68, ISBN 978-0-691-12048-5

Further reading

- Swagato Ganguly (2017). Idolatry and The Colonial Idea of India: Visions of Horror, Allegories of Enlightenment. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138106161

- Reuven Chaim Klein (2018). God versus Gods: Judaism in the Age of Idolatry. Mosaica Press. ISBN 978-1946351463.

- Yechezkel Kaufmann (1960). The Religion of Israel: From its Beginnings to the Babylonin Exile. Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0805203646.

- Faur, José; Faur, Jose (1978), "The Biblical Idea of Idolatry", The Jewish Quarterly Review 69 (1): 1–15, doi:

- Brichto, Herbert Chanan (1983), "The Worship of the Golden Calf: A Literary Analysis of a Fable on Idolatry", Hebrew Union College Annual 54: 1–44

- Pfeiffer, Robert H. (1924), "The Polemic against Idolatry in the Old Testament", Journal of Biblical Literature 43 (3/4): 229–240, doi:

- Bakan, David (1961), "Idolatry in Religion and Science", The Christian Scholar 44 (3): 223–230

- Siebert, Donald T. (1984), "Hume on Idolatry and Incarnation", Journal of the History of Ideas 45 (3): 379–396, doi:

- Orellana, Sandra L. (1981), "Idols and Idolatry in Highland Guatemala", Ethnohistory 28 (2): 157–177, doi:

وصلات خارجية

- Idolatry and iconoclasm, Tufts University

- Iconoclasm and idolatry, Columbia University