بقعة قمامة

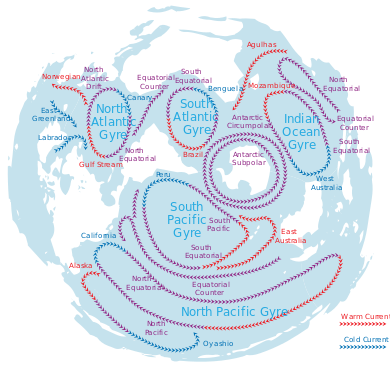

بقعة القمامة هي دوامة من حبيبات نفايات بحرية تسببت فيها آثار تيارات محيطية وتلوث متزايد بالبلاستيك من البشر. إن هذه التجمعات من البلاستيك والنفايات الأخرى التي يتسبب فيها البشر مسؤولة عن مشاكل بيئية وإيكولوجية تؤثر على الحياة البحرية، وتلوث المحيطات بالمواد الكيميائية السامة، وتساهم في انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة. وبمجرد أن تنتقل النفايات البحرية إلى المياه، فإنها تصبح متحركة. ويمكن أن تتطاير النفايات بفعل الرياح، أو تتبع تدفق التيارات المحيطية، وغالبًا ما ينتهي بها الأمر في منتصف الدوامات المحيطية حيث تكون التيارات أضعف.

داخل بقع القمامة، لا تكون النفايات متماسكة، ورغم أن معظمها يقع بالقرب من سطح المحيط، إلا أنه يمكن العثور عليها على عمق يصل إلى أكثر من 30 مترًا تحت سطح الماء.[1] تحتوي البقع على بلاستيك ونفايات بأحجام مختلفة تتراوح من الميكروبلاستيك وحبيبات البلاستيك على نطاق صغير، إلى نفايات كبيرة مثل شبكات الصيد والسلع الاستهلاكية والأجهزة المفقودة بسبب الفيضانات وخسائر الشحن.

تزداد بقع القمامة بسبب فقدان البلاستيك واسع النطاق أنظمة جمع القمامة البشرية. وقد قدر برنامج الأمم المتحدة للبيئة أن "لكل ميل مربع من المحيط" يوجد حوالي "46.000 قطعة من البلاستيك".[2] أكبر 10 دول مصدر لتلوث البلاستيك في المحيطات على مستوى العالم هي، من الأكثر إلى الأقل، الصين، وإندونيسيا، والفلپين، وڤيتنام، وسريلانكا، وتايلند، ومصر، وماليزيا، ونيجيريا، وبنگلادش،[3] ومعظمها عن طريق أنهار يانگتسى، السند، الأصفر، هاي، النيل، الگانج، اللؤلؤ، آمور، النيجر، ومكونگ، والتي تمثل "90 في المائة من إجمالي البلاستيك الذي يصل إلى محيطات العالم".[4][5] كانت آسيا المصدر الرئيسي للنفايات البلاستيكية التي أديرت بشكل سيئ، حيث بلغت حصة الصين وحدها 2.4 مليون طن متري.[6]

أشهر هذه البقع هي بقعة قمامة الهادي الكبرى، والتي تحتوي على أعلى كثافة من النفايات البحرية والبلاستيك. تحتوي بقعة قمامة الهادي على تراكمين كبيرين: بقعة القمامة الغربية وبقعة القمامة الشرقية، الأولى قبالة ساحل اليابان والثانية بين هاواي وكاليفورنيا. تحتوي بقع القمامة هذه على 90 مليون طن من النفايات.[1] تشمل البقع الأخرى المعروفة بقعة قمامة شمال الأطلسي بين أمريكا الشمالية وأفريقيا، وبقعة قمامة جنوب الأطلسي الواقعة بين شرق أمريكا الجنوبية وطرف أفريقيا، وبقعة قمامة جنوب الهادي الواقعة غرب أمريكا الجنوبية، وبقعة قمامة المحيط الهندي الواقعة شرق جنوب أفريقيا مدرجة حسب تناقص حجمها.[7]

البقع المعروفة

In 2014, there were five areas across all the oceans where the majority of plastic concentrated.[8] Researchers collected a total of 3070 samples across the world to identify hot spots of surface level plastic pollution. The pattern of distribution closely mirrored models of oceanic currents with the North Pacific Gyre, or Great Pacific Garbage Patch, being the highest density of plastic accumulation. The other four garbage patches include the North Atlantic garbage patch between the North America and Africa, the South Atlantic garbage patch located between eastern South America and the tip of Africa, the South Pacific garbage patch located west of South America, and the Indian Ocean garbage patch found east of South Africa.[8]

الكبرى بالهادي

جنوب الهادي

المحيط الهندي

شمال الأطلسي

القضايا البيئية

التحلل الضوئي للبلاستيك

The North Atlantic patch is one of several oceanic regions where researchers have studied the effects and impact of plastic photodegradation in the neustonic layer of water.[9] Unlike organic debris, which biodegrades, plastic disintegrates into ever smaller pieces while remaining a polymer (without changing chemically). This process continues down to the molecular level.[10] Some plastics decompose within a year of entering the water, releasing potentially toxic chemicals such as bisphenol A, PCBs and derivatives of polystyrene.[11]

As the plastic flotsam photodegrades into smaller and smaller pieces, it concentrates in the upper water column. As it disintegrates, the pieces become small enough to be ingested by aquatic organisms that reside near the ocean's surface. Plastic may become concentrated in neuston, thereby entering the food chain. Disintegration means that much of the plastic is too small to be seen. Moreover, plastic exposed to sunlight and in watering environments produce greenhouse gases, leading to further environmental impact.[12]

Effects on marine life

The 2017 United Nations Ocean Conference estimated that the oceans might contain more weight in plastics than fish by the year 2050.[13] Some long-lasting plastics end up in the stomachs of marine animals.[14][15][16] Plastic attracts seabirds and fish. When marine life consumes plastic allowing it to enter the food chain, this can lead to greater problems when species that have consumed plastic are then eaten by other predators.

Animals can also become trapped in plastic nets and rings, which can cause death. Plastic pollution affects at least 700 marine species, including sea turtles, seals, seabirds, fish, whales, and dolphins.[17] Cetaceans have been sighted within the patch, which poses entanglement and ingestion risks to animals using the Great Pacific garbage patch as a migration corridor or core habitat.[18]

Plastic consumption

With the increased amount of plastic in the ocean, living organisms are now at a greater risk of harm from plastic consumption and entanglement. Approximately 23% of aquatic mammals, and 36% of seabirds have experienced the detriments of plastic presence in the ocean.[19] Since as much as 70% of the trash is estimated to be on the ocean floor, and microplastics are only millimeters wide, sealife at nearly every level of the food chain is affected.[20][21][22] Animals who feed off of the bottom of the ocean risk sweeping microplastics into their systems while gathering food.[23] Smaller marine life such as mussels and worms sometimes mistake plastic for their prey.[19][24]

Larger animals are also affected by plastic consumption because they feed on fish, and are indirectly consuming microplastics already trapped inside their prey.[23] Likewise, humans are also susceptible to microplastic consumption. People who eat seafood also eat some of the microplastics that were ingested by marine life. Oysters and clams are popular vehicles for human microplastic consumption.[23] Animals who are within the general vicinity of the water are also affected by the plastic in the ocean. Studies have shown 36% species of seabirds are consuming plastic because they mistake larger pieces of plastic for food.[19] Plastic can cause blockage of intestines as well as tearing of interior stomach and intestinal lining of marine life, ultimately leading to starvation and death.[19]

Entanglement

Not all marine life is affected by the consumption of plastic. Some instead find themselves tangled in larger pieces of garbage that cause just as much harm as the barely visible microplastics.[19] Trash that has the possibility of wrapping itself around a living organism may cause strangulation or drowning.[19] If the trash gets stuck around a ligament that is not vital for airflow, the ligament may grow with a malformation.[19] Plastic's existence in the ocean becomes cyclical because marine life that is killed by it ultimately decompose in the ocean, re-releasing the plastics into the ecosystem.[25][26]

Deposits on landmasses

Research in 2017[27] reported "the highest density of plastic rubbish anywhere in the world" on remote and uninhabited Henderson Island in South Pacific as a result of the South Pacific Gyre. The beaches contained an estimated 37.7 million items of debris together weighing 17.6 tonnes. In a study transect on North Beach, each day 17 to 268 new items washed up on a 10-metre section.[28][29][30]

المراجع

- ^ أ ب "Marine Debris in the North Pacific A Summary of Existing Information and Identification of Data Gaps" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. 24 July 2015.

- ^ Maser, Chris (2014). Interactions of Land, Ocean and Humans: A Global Perspective. CRC Press. pp. 147–48. ISBN 978-1482226393.

- ^ Jambeck, Jenna R.; Geyer, Roland; Wilcox, Chris (12 February 2015). "Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean" (PDF). Science. 347 (6223): 769. Bibcode:2015Sci...347..768J. doi:10.1126/science.1260352. PMID 25678662. S2CID 206562155. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Christian Schmidt; Tobias Krauth; Stephan Wagner (11 October 2017). "Export of Plastic Debris by Rivers into the Sea" (PDF). Environmental Science & Technology. 51 (21): 12246–12253. Bibcode:2017EnST...5112246S. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b02368. PMID 29019247.

The 10 top-ranked rivers transport 88–95% of the global load into the sea

- ^ Franzen, Harald (30 November 2017). "Almost all plastic in the ocean comes from just 10 rivers". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

It turns out that about 90 percent of all the plastic that reaches the world's oceans gets flushed through just 10 rivers: The Yangtze, the Indus, Yellow River, Hai River, the Nile, the Ganges, Pearl River, Amur River, the Niger, and the Mekong (in that order).

- ^ Robert Lee Hotz (13 February 2015). "Asia Leads World in Dumping Plastic in Seas". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015.

- ^ Cózar, Andrés; Echevarría, Fidel; González-Gordillo, J. Ignacio; Irigoien, Xabier; Úbeda, Bárbara; Hernández-León, Santiago; Palma, Álvaro T.; Navarro, Sandra; García-de-Lomas, Juan; Ruiz, Andrea; Fernández-de-Puelles, María L. (2014-07-15). "Plastic debris in the open ocean". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (in الإنجليزية). 111 (28): 10239–10244. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11110239C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1314705111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4104848. PMID 24982135.

- ^ أ ب Cózar, Andrés; Echevarría, Fidel; González-Gordillo, J. Ignacio; Irigoien, Xabier; Úbeda, Bárbara; Hernández-León, Santiago; Palma, Álvaro T.; Navarro, Sandra; García-de-Lomas, Juan; Ruiz, Andrea; Fernández-de-Puelles, María L. (2014-07-15). "Plastic debris in the open ocean". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (in الإنجليزية). 111 (28): 10239–10244. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11110239C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1314705111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4104848. PMID 24982135.

- ^ Thompson, R. C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R. P.; Davis, A.; Rowland, S. J.; John, A. W.; McGonigle, D.; Russell, A. E. (2004). "Lost at Sea: Where is All the Plastic?". Science. 304 (5672): 838. doi:10.1126/science.1094559. PMID 15131299. S2CID 3269482.

- ^ Barnes, D. K. A.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R. C.; Barlaz, M. (2009). "Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 364 (1526): 1985–98. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0205. JSTOR 40485977. PMC 2873009. PMID 19528051.

- ^ Barry, Carolyn (20 August 2009). "Plastic Breaks Down in Ocean, After All – And Fast". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ Royer, Sarah-Jeanne; Ferrón, Sara; Wilson, Samuel T.; Karl, David M. (2018-08-01). "Production of methane and ethylene from plastic in the environment". PLOS ONE (in الإنجليزية). 13 (8): e0200574. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1300574R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200574. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6070199. PMID 30067755.

- ^ Wright, Pam (6 June 2017). "UN Ocean Conference: Plastics Dumped In Oceans Could Outweigh Fish by 2050, Secretary-General Says". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Moore, Charles (November 2003). "Across the Pacific Ocean, plastics, plastics, everywhere". Natural History Magazine.

- ^ Holmes, Krissy (18 January 2014). "Harbour snow dumping dangerous to environment: biologist". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "Jan Pronk". Public Radio International. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014.

- ^ "These 5 Marine Animals Are Dying Because of Our Plastic Trash… Here's How We Can Help". One Green Planet (in الإنجليزية). 2019-04-22. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- ^ Gibbs, Susan E.; Salgado Kent, Chandra P.; Slat, Boyan; Morales, Damien; Fouda, Leila; Reisser, Julia (9 April 2019). "Cetacean sightings within the Great Pacific Garbage Patch". Marine Biodiversity. 49 (4): 2021–27. Bibcode:2019MarBd..49.2021G. doi:10.1007/s12526-019-00952-0.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Sigler, Michelle (2014-10-18). "The Effects of Plastic Pollution on Aquatic Wildlife: Current Situations and Future Solutions". Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (in الإنجليزية). 225 (11): 2184. Bibcode:2014WASP..225.2184S. doi:10.1007/s11270-014-2184-6. ISSN 1573-2932. S2CID 51944658.

- ^ Perkins, Sid (17 December 2014). "Plastic waste taints the ocean floors". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2014.16581. S2CID 138018931.

- ^ Handwerk, Brian (2009). "Giant Ocean-Trash Vortex Attracts Explorers". National Geographic. Archived from the original on August 3, 2009.

- ^ Ivar Do Sul, Juliana A.; Costa, Monica F. (2014-02-01). "The present and future of microplastic pollution in the marine environment". Environmental Pollution (in الإنجليزية). 185: 352–364. Bibcode:2014EPoll.185..352I. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2013.10.036. ISSN 0269-7491. PMID 24275078.

- ^ أ ب ت "Marine Plastics". Smithsonian Ocean (in الإنجليزية). 30 April 2018. Retrieved 2019-11-08.

- ^ Kaiser, Jocelyn (2010-06-18). "The Dirt on Ocean Garbage Patches". Science (in الإنجليزية). 328 (5985): 1506. Bibcode:2010Sci...328.1506K. doi:10.1126/science.328.5985.1506. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 20558704.

- ^ "Plastic pollution found inside dead seabirds". www.scotsman.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2019-11-08.

- ^ "Pygmy sperm whale died in Halifax Harbour after eating plastic". CBC News. 16 March 2015.

- ^ Lavers, Jennifer L.; Bond, Alexander L. (2017). "Exceptional and rapid accumulation of anthropogenic debris on one of the world's most remote and pristine islands". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (23): 6052–6055. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.6052L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1619818114. PMC 5468685. PMID 28507128.

- ^ Cooper, Dani (16 May 2017). "Remote South Pacific island has highest levels of plastic rubbish in the world". ABC News Online.

- ^ Hunt, Elle (15 May 2017). "38 million pieces of plastic waste found on uninhabited South Pacific island". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ "No one lives on this remote Pacific island – but it's covered in 38 million pieces of our trash". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 May 2017.