ثنائي الفنيل متعدد الكلورة

التركيب الكيميائي لثنائي الفنيل متعدد الكلورة. المواقع المحتملة لذرات الكلور على حلقات البنزين موضحة بالأرقام المعينة لذرات الكربون.

| |

| المُعرِّفات | |

|---|---|

| رقم CAS | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.014.226 |

| UN number | UN 2315 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| الخصائص | |

| الصيغة الجزيئية | C12H10−xClx |

| كتلة مولية | Variable |

| المظهر | سوائل زيتية، سميكة بلا لون أو ذات لون أصفر فاتح[1] |

| المخاطر | |

| NFPA 704 (معيـَّن النار) | |

ما لم يُذكر غير ذلك، البيانات المعطاة للمواد في حالاتهم العيارية (عند 25 °س [77 °ف]، 100 kPa). | |

| مراجع الجدول | |

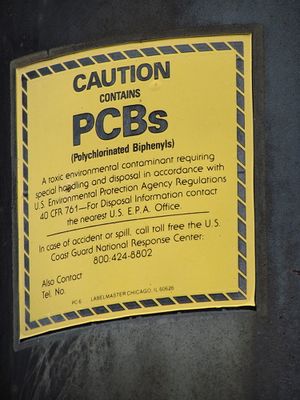

ثنائي الفنيل متعدد الكلورة Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB)، هو مركب كلور عضوي صيغته الكيميائية C12H10−xClx. انتشرت مركبات ثنائي الفنيل متعدد الكلورة بشكل كبير كسوائل مادة عازلة كهربائياً ومبردة في الأجهزة الكهربائية، ورق النسخ الخالي من الكربون والسوائل الناقلة للحرارة.[2]

لاستدامتها الطويلة، لا تزال مركبات ثنائي الفنيل متعدد الكلورة مستخدمة حتى الآن، برغم تراجع تصنيعها بشكل كبير منذ الستينيات، عندما ظهرت مجموعة من المشكلات.[3] مع اكتشاف السمية البيئية لهذه المركبات، وتصنيفها كملوثات عضوية ثابتة، حُظر انتجاها بموجب القانون الفدرالي الأمريكي عام 1978، وبموجب مبادرة ستوكهولم للملوثات العضوية الثابتة عام 2001.[4] الوكالة الدولية لأبحاث السرطان، حددت مركبات ثنائي الفنيل متعددة الكلورة كمسرطنات بالنسبة للبشر. تبعاً للوكالة الأمريكية للحماية البيئية، فمركبات ثنائي الفنيل متعددة الكلورة تسبب السرطان للحيوانات وهي مسرطنات محتملة للبشر.[5] الكثير من الأنهار والمباني، منها المدارس، المنتزهات، ومواقع أخرى، ملوثة بمركبات ثنائي الفنيل متعدد الكلورة كما يوجد تلوث في المواد الغذائية بهذه المواد.

بعض مركبات ثنائي الفنيل متعدد الكلورة تتشارك تركيب وآلية سمية مماثلة للديوكسينات.[6] الآثار السمية الأخرى المعروفة اضطراب الغدد الصماء (وأشهرها حصر وظيفة الغدة الدرقية) والتسمم العصبي.[7] يبلغ الحد الأقصى المسموح به لمستوى الملوثات في مياه الشرب في الولايات المتحدة صفر، لكن بسبب قيود تقنيات معالجة المياه، فإن المستوى الفعلي هو 0.5 جزء لكل بليون.[8]

نظائر البروم لمركبات ثنائي الفنيل متعددة الكلورة هي مركبات ثنائي الفنيل متعدد البرومة (PBBs)، التي تستخدم في تطبيقات مناظرة ولديها تأثيرات بيئية مشابهة.

الخصائص الفيزيائية والكيميائية

الخصائص الفيزيائية

The compounds are pale-yellow viscous liquids. They are hydrophobic, with low water solubilities: 0.0027–0.42 ng/L for Aroclors,[9][صفحة مطلوبة] but they have high solubilities in most organic solvents, oils, and fats. They have low vapor pressures at room temperature. They have dielectric constants of 2.5–2.7,[10] very high thermal conductivity,[9][صفحة مطلوبة] and high flash points (from 170 to 380 °C).[9][صفحة مطلوبة]

The density varies from 1.182 to 1.566 g/cm3.[9][صفحة مطلوبة] Other physical and chemical properties vary widely across the class. As the degree of chlorination increases, melting point and lipophilicity increase, and vapour pressure and water solubility decrease.[9][صفحة مطلوبة]

PCBs do not easily break down or degrade, which made them attractive for industries. PCB mixtures are resistant to acids, bases, oxidation, hydrolysis, and temperature change.[11] They can generate extremely toxic dibenzodioxins and dibenzofurans through partial oxidation. Intentional degradation as a treatment of unwanted PCBs generally requires high heat or catalysis (see Methods of destruction below).

PCBs readily penetrate skin, PVC (polyvinyl chloride), and latex (natural rubber).[12] PCB-resistant materials include Viton, polyethylene, polyvinyl acetate (PVA), polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), butyl rubber, nitrile rubber, and Neoprene.[12]

التركيب والسمية

PCBs are derived from biphenyl, which has the formula C12H10, sometimes written (C6H5)2. In PCBs, some of the hydrogen atoms in biphenyl are replaced by chlorine atoms. There are 209 different chemical compounds in which one to ten chlorine atoms can replace hydrogen atoms. PCBs are typically used as mixtures of compounds and are given the single identifying CAS number 1336-36-3 . About 130 different individual PCBs are found in commercial PCB products.[9]

Toxic effects vary depending on the specific PCB. In terms of their structure and toxicity, PCBs fall into two distinct categories, referred to as coplanar or non-ortho-substituted arene substitution patterns and noncoplanar or ortho-substituted congeners.

الأسماء البديلة

Commercial PCB mixtures were marketed under the following names:[13][14]

|

البرازيل

الشيك وسلوڤاكيا

فرنسا

ألمانيا

إيطاليا

|

اليابان

الاتحاد السوڤيتي السابق

المملكة المتحدة

|

الولايات المتحدة

|

الإنتاج

One estimate (2006) suggested that 1 million tonnes of PCBs had been produced. 40% of this material was thought to remain in use.[2] Another estimate put the total global production of PCBs on the order of 1.5 million tonnes. The United States was the single largest producer with over 600,000 tonnes produced between 1930 and 1977. The European region follows with nearly 450,000 tonnes through 1984. It is unlikely that a full inventory of global PCB production will ever be accurately tallied, as there were factories in Poland, East Germany, and Austria that produced unknown amounts of PCBs. In East region of Slovakia there is still 21 500 tons of PCBs stored. [16]

التطبيقات

The utility of PCBs is based largely on their chemical stability, including low flammability and high dielectric constant. In an electric arc, PCBs generate incombustible gases.

Use of PCBs is commonly divided into closed and open applications.[2] Examples of closed applications include coolants and insulating fluids (transformer oil) for transformers and capacitors, such as those used in old fluorescent light ballasts,[17] hydraulic fluids, lubricating and cutting oils, and the like. In contrast, the major open application of PCBs was in carbonless copy ("NCR") paper, which even presently results in paper contamination.[18]

Other open applications were as plasticizers in paints and cements, stabilizing additives in flexible PVC coatings of electrical cables and electronic components, pesticide extenders, reactive flame retardants and sealants for caulking, adhesives, wood floor finishes, such as Fabulon and other products of Halowax in the U.S.,[19] de-dusting agents, waterproofing compounds, casting agents.[9] It was also used as a plasticizer in paints and especially "coal tars" that were used widely to coat water tanks, bridges and other infrastructure pieces.

النقل والتحولات البيئية

PCBs have entered the environment through both use and disposal. The environmental fate of PCBs is complex and global in scale.[9]

الماء

Because of their low vapour pressure, PCBs accumulate primarily in the hydrosphere, despite their hydrophobicity, in the organic fraction of soil, and in organisms.[بحاجة لمصدر] The hydrosphere is the main reservoir. The immense volume of water in the oceans is still capable of dissolving a significant quantity of PCBs.[بحاجة لمصدر]

As the pressure of ocean water increases with depth, PCBs become heavier than water and sink to the deepest ocean trenches where they are concentrated.[20]

الهواء

A small volume of PCBs has been detected throughout the earth's atmosphere. The atmosphere serves as the primary route for global transport of PCBs, particularly for those congeners with one to four chlorine atoms.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In the atmosphere, PCBs may be degraded by hydroxyl radicals, or directly by photolysis of carbon–chlorine bonds (even if this is a less important process).[بحاجة لمصدر]

Atmospheric concentrations of PCBs tend to be lowest in rural areas, where they are typically in the picogram per cubic meter range, higher in suburban and urban areas, and highest in city centres, where they can reach 1 ng/m3 or more.[بحاجة لمصدر] In Milwaukee, an atmospheric concentration of 1.9 ng/m3 has been measured, and this source alone was estimated to account for 120 kg/year of PCBs entering Lake Michigan.[21] In 2008, concentrations as high as 35 ng/m3, 10 times higher than the EPA guideline limit of 3.4 ng/m3, have been documented inside some houses in the U.S.[19]

Volatilization of PCBs in soil was thought to be the primary source of PCBs in the atmosphere, but research suggests ventilation of PCB-contaminated indoor air from buildings is the primary source of PCB contamination in the atmosphere.[22]

الغلاف الجوي

In biosphere, PCBs can be degraded by either bacteria or eukaryotes, but the speed of the reaction depends on both the number and the disposition of chlorine atoms in the molecule: less substituted, meta- or para-substituted PCBs undergo biodegradation faster than more substituted congeners.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In bacteria, PCBs may be dechlorinated through reductive dechlorination, or oxidized by dioxygenase enzyme.[بحاجة لمصدر] In eukaryotes, PCBs may be oxidized by the cytochrome P450 enzyme.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Like many lipiphilic toxins, PCBs biomagnify up the food chain. For instance, ducks can accumulate PCBs from eating fish and other aquatic life from contaminated rivers, and these can cause harm to human health or even death when eaten.[23] PCBs can be transported by birds from aquatic sources onto land via feces and carcasses.[24]

الأيض الكيميائي-الحيوي

نظرة عامة

PCBs undergo xenobiotic biotransformation, a mechanism used to make lipophilic toxins more polar and more easily excreted from the body.[25] The biotransformation is dependent on the number of chlorine atoms present, along with their position on the rings. Phase I reactions occur by adding an oxygen to either of the benzene rings by Cytochrome P450.[26] The type of P450 present also determines where the oxygen will be added; phenobarbital (PB)-induced P450s catalyze oxygenation to the meta-para positions of PCBs while 3-methylcholanthrene (3MC)-induced P450s add oxygens to the ortho–meta positions.[27] PCBs containing ortho–meta and meta–para protons can be metabolized by either enzyme, making them the most likely to leave the organism. However, some metabolites of PCBs containing ortho–meta protons have increased steric hindrance from the oxygen, causing increased stability and an increased chance of accumulation.[28]

حسب النوع

Metabolism is also dependent on the species of organism; different organisms have slightly different P450 enzymes that metabolize certain PCBs better than others. Looking at the PCB metabolism in the liver of four sea turtle spieces (green, olive ridley, loggerhead and hawksbill), green and hawksbill sea turtles have noticeably higher hydroxylation rates of PCB 52 than olive ridley or loggerhead sea turtles. This is because the green and hawksbill sea turtles have higher P450 2-like protein expression. This protein adds three hydroxyl groups to PCB 52, making it more polar and water-soluble. P450 3-like protein expression that is thought to be linked to PCB 77 metabolism, something that was not measured in this study.[25]

حسب درجة الحرارة

Temperature plays a key role in the ecology, physiology and metabolism of aquatic species. The rate of PCB metabolism was temperature dependent in yellow perch (Perca flavescens). In fall and winter, only 11 out of 72 introduced PCB congeners were excreted and had halflives of more than 1,000 days. During spring and summer when the average daily water temperature was above 20 °C, persistent PCBs had halflives of 67 days. The main excretion processes were fecal egestion, growth dilution and loss across respiratory surfaces. The excretion rate of PCBs matched with the perch's natural bioenergetics, where most of their consumption, respiration and growth rates occur during the late spring and summer. Since the perch is performing more functions in the warmer months, it naturally has a faster metabolism and has less PCB accumulation. However, multiple cold-water periods mixed with toxic PCBs with coplanar chlorine molecules can be detrimental to perch health.[29]

حسب الجنس

Enantiomers of chiral compounds have similar chemical and physical properties, but can be metabolized by the body differently. This was looked at in bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) for two main reasons: they are large animals with slow metabolisms (meaning PCBs will accumulate in fatty tissue) and few studies have measured chiral PCBs in cetaceans. They found that the average PCB concentrations in the blubber were approximately four times higher than the liver; however, this result is most likely age- and sex-dependent. As reproductively active females transferred PCBs and other poisonous substances to the fetus, the PCB concentrations in the blubber were significantly lower than males of the same body length (less than 13 meters).[30]

الآثار الصحية

The toxicity of PCBs varies considerably among congeners. The coplanar PCBs, known as nonortho PCBs because they are not substituted at the ring positions ortho to (next to) the other ring, (such as PCBs 77, 126 and 169), tend to have dioxin-like properties, and generally are among the most toxic congeners. Because PCBs are almost invariably found in complex mixtures, the concept of toxic equivalency factors (TEFs) has been developed to facilitate risk assessment and regulation, where more toxic PCB congeners are assigned higher TEF values on a scale from 0 to 1. One of the most toxic compounds known, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo[p]dioxin, a PCDD, is assigned a TEF of 1.[31]

التعرض والإفراز

In general, people are exposed to PCBs overwhelmingly through food, much less so by breathing contaminated air, and least by skin contact. Once exposed, some PCBs may change to other chemicals inside the body. These chemicals or unchanged PCBs can be excreted in feces or may remain in a person's body for years, with half lives estimated at 10–15 years.[32] PCBs collect in body fat and milk fat.[33] PCBs biomagnify up the food web and are present in fish and waterfowl of contaminated aquifers.[34] Human infants are exposed to PCBs through breast milk or by intrauterine exposure through transplacental transfer of PCBs [33] and are at the top of the food chain.[35]

العلامات والأعراض

البشر

The most commonly observed health effects in people exposed to extremely high levels of PCBs are skin conditions, such as chloracne and rashes, but these were known to be symptoms of acute systemic poisoning dating back to 1922. Studies in workers exposed to PCBs have shown changes in blood and urine that may indicate liver damage. In Japan in 1968, 280 kg of PCB-contaminated rice bran oil was used as chicken feed, resulting in a mass poisoning, known as Yushō disease, in over 1800 people.[36] Common symptoms included dermal and ocular lesions, irregular menstrual cycles and lowered immune responses.[37][38][39] Other symptoms included fatigue, headaches, coughs, and unusual skin sores.[40] Additionally, in children, there were reports of poor cognitive development.[37] Women exposed to PCBs before or during pregnancy can give birth to children with lowered cognitive ability, immune compromise, and motor control problems.[41][42][43]

There is evidence that crash dieters that have been exposed to PCBs have an elevated risk of health complications. Stored PCBs in the adipose tissue becomes mobilized into the blood when individuals begin to crash diet.[44] PCBs have shown toxic and mutagenic effects by interfering with hormones in the body. PCBs, depending on the specific congener, have been shown to both inhibit and imitate estradiol, the main sex hormone in females. Imitation of the estrogen compound can feed estrogen-dependent breast cancer cells, and possibly cause other cancers, such as uterine or cervical. Inhibition of estradiol can lead to serious developmental problems for both males and females, including sexual, skeletal, and mental development issues.[بحاجة لمصدر][45] In a cross-sectional study, PCBs were found to be negatively associated with testosterone levels in adolescent boys.[46]

High PCB levels in adults have been shown to result in reduced levels of the thyroid hormone triiodothyronine, which affects almost every physiological process in the body, including growth and development, metabolism, body temperature, and heart rate. It also resulted in reduced immunity and increased thyroid disorders.[32][47]قالب:Ums

الحيوانات

السرطان

In 2013, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified dioxin-like PCBs as human carcinogens.[48] According to the U.S. EPA, PCBs have been shown to cause cancer in animals and evidence supports a cancer-causing effect in humans.[5] Per the EPA, studies have found increases in malignant melanoma and rare liver cancers in PCB workers.[5]

In 2013, the International Association for Research on Cancer (IARC) determined that the evidence for PCBs causing non-Hodgkin lymphoma is "limited" and "not consistent".[48] In contrast an association between elevated blood levels of PCBs and non-Hodgkin lymphoma had been previously accepted.[49] PCBs may play a role in the development of cancers of the immune system because some tests of laboratory animals subjected to very high doses of PCBs have shown effects on the animals' immune system, and some studies of human populations have reported an association between environmental levels of PCBs and immune response.[5]

التاريخ

التلوث

بلجيكا

إيطاليا

اليابان

جمهورية أيرلندا

كينيا

سلوڤاكيا

سلوڤنيا

المملكة المتحدة

إسپانيا

الولايات المتحدة

التنظيم

In 1972 the Japanese government banned the production, use, and import of PCBs.[9][صفحة مطلوبة]

In 1973, the use of PCBs in "open" or "dissipative" sources, such as plasticisers in paints and cements, casting agents, fire retardant fabric treatments and heat stabilizing additives for PVC electrical insulation, adhesives, paints and waterproofing, railroad ties was banned in Sweden.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In 1976, concern over the toxicity and persistence (chemical stability) of PCBs in the environment led the United States Congress to ban their domestic production, effective January 1, 1978, via the Toxic Substances Control Act.[50][51] As the agency that was charged with implementing TSCA, the EPA banned new manufacturing of PCBs, but it allowed their continued use for electrical equipment for economic reasons[52]. In 1979 and future years, the EPA continued to regulate PCB usage and disposal.[53]

In 1981, the UK banned closed uses of PCBs in new equipment, and nearly all UK PCB synthesis ceased; closed uses in existing equipment containing in excess of 5 litres of PCBs were not stopped until December 2000.[54]

طرق التدمير

الفيزيائية

PCBs are technically attractive because of their inertness, which includes their resistance to combustion. Nonetheless, they can be effectively destroyed by incineration at 1000 °C. When combusted at lower temperatures, they convert in part to more hazardous materials, including dibenzofurans and dibenzodioxins. When conducted properly, the combustion products are water, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen chloride. In some cases, the PCBs are combusted as a solution in kerosene. PCBs have also been destroyed by pyrolysis in the presence of alkali metal carbonates.[2]

Thermal desorption is highly effective at removing PCBs from soil.[55]

الكيميائية

PCBs are fairly chemically unreactive, this property being attractive for its application as an inert material. They resist oxidation.[56] Many chemical compounds are available to destroy or reduce the PCBs. Commonly, PCBs are degraded by basis mixtures of glycols, which displace some or all chloride. Also effective are reductants such as sodium or sodium naphthenide.[2] Vitamin B12 has also shown promise.[57]

الميكروبية

Some micro-organisms degrade PCBs by reducing the C-Cl bonds. Microbial dechlorination tends to be rather slow-acting in comparison to other methods. Enzymes extracted from microbes can show PCB activity. In 2005, Shewanella oneidensis biodegraded a high percentage of PCBs in soil samples.[58] A low voltage current can stimulate the microbial degradation of PCBs.[59]

الفطرية

There is research showing that some ligninolytic fungi can degrade PCBs.[60]

المتناظرات

| PCB homolog | CASRN | Cl substituents | Number of congeners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biphenyl (not a PCB) | 92-52-4 | 0 | 1 |

| Monochlorobiphenyl | 27323-18-8 | 1 | 3 |

| Dichlorobiphenyl | 25512-42-9 | 2 | 12 |

| Trichlorobiphenyl | 25323-68-6 | 3 | 24 |

| Tetrachlorobiphenyl | 26914-33-0 | 4 | 42 |

| Pentachlorobiphenyl | 25429-29-2 | 5 | 46 |

| Hexachlorobiphenyl | 26601-64-9 | 6 | 42 |

| Heptachlorobiphenyl | 28655-71-2 | 7 | 24 |

| Octachlorobiphenyl | 55722-26-4 | 8 | 12 |

| Nonachlorobiphenyl | 53742-07-7 | 9 | 3 |

| Decachlorobiphenyl | 2051-24-3 | 10 | 1 |

انظر أيضاً

- Bay mud

- Organochlorine compound

- Polybrominated biphenyl

- Zodiac, a novel by Neal Stephenson which involves PCBs and their impact on the environment.

المصادر

- ^ "Hazardous Substance Fact Sheet" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Health.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Rossberg, Manfred; Lendle, Wilhelm; Pfleiderer, Gerhard; Tögel, Adolf; Dreher, Eberhard-Ludwig; Langer, Ernst; Rassaerts, Heinz; Kleinschmidt, Peter; Strack (2006). "Chlorinated Hydrocarbons". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a06_233.pub2.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|authors=(help) - ^ Robertson, Larry W.; Hansen, Larry G., eds. (2001). PCBs: Recent advances in environmental toxicology and health effects. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. p. 11. ISBN 978-0813122267.

- ^ Porta, M.; Zumeta, E. (2002). "Implementing the Stockholm Treaty on Persistent Organic Pollutants". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 59 (10): 651–2. doi:10.1136/oem.59.10.651. PMC 1740221. PMID 12356922.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Health Effects of PCBs". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 13 June 2013.

- ^ "Dioxins and PCBs". European Food Safety Authority. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ Boas, Malene; Feldt-Rasmussen, Ulla; Skakkebaek, Niels; Main, Katharina (May 1, 2006). "Environmental chemicals and thyroid function". European Journal of Endocrinology. 154 (5): 599–611. doi:10.1530/eje.1.02128. PMID 16645005. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ "Consumer Factsheet on Polychlorinated Biphenyls" (PDF). National Primary Drinking Water Regulations. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. May 14, 2009.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ UNEP Chemicals (1999). Guidelines for the Identification of PCBs and Materials Containing PCBs (PDF). United Nations Environment Programme. p. 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-14. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "PCB Transformers and Capacitors from management to Reclassification to Disposal" (PDF). chem.unep.ch. United Nations Environmental Program. pp. 55, 63. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-06-21. Retrieved 2014-12-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kimbrough, R. D.; Jensen, A. A. (2012). Halogenated Biphenyls, Terphenyls, Naphthalenes, Dibenzodioxins and Related Products (in الإنجليزية). Elsevier. p. 24. ISBN 9780444598929.

- ^ أ ب Identifying PCB-Containing Capacitors (PDF). Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council. 1997. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-642-54507-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-03. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Proceedings of the Subregional Awareness Raising Workshop on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), Bangkok, Thailand". United Nations Environment Programme. 25 November 1997. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Brand names of PCBs — What are PCBs?". Japan Offspring Fund / Center for Marine Environmental Studies (CMES), Ehime University, Japan. 2003. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ^ Erickson, Mitchell D.; Kaley, II, Robert G. "Applications of polychlorinated biphenyls" (PDF). Springer-Verlag. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- ^ Breivik, K.; Sweetman, A.; Pacyna, J.; Jones, K. (2002). "Towards a global historical emission inventory for selected PCB congeners — a mass balance approach: 1. Global production and consumption". The Science of the Total Environment. 290 (1–3): 181–98. Bibcode:2002ScTEn.290..181B. doi:10.1016/S0048-9697(01)01075-0. PMID 12083709.

- ^ Godish, T. (2001). Indoor environmental quality (1st ed.). Boca Raton, FL: Lewis Publishers. pp. 110–30.

- ^ Pivnenko, K.; Olsson, M. E.; Götze, R.; Eriksson, E.; Astrup, T. F. (2016). "Quantification of chemical contaminants in the paper and board fractions of municipal solid waste". Waste Management. 51: 43–54. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2016.03.008. PMID 26969284.

- ^ أ ب Rudel, Ruthann A.; Seryak, Liesel M.; Brody, Julia G. (2008). "PCB-containing wood floor finish is a likely source of elevated PCBs in residents' blood, household air and dust: A case study of exposure". Environmental Health. 7: 2. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-7-2. PMC 2267460. PMID 18201376.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Nasty chemicals abound in what was thought an untouched environment". The Economist. 2017-02-18. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Wethington, David M.; Hornbuckle, Keri C. (2005). "Milwaukee, WI, as a Source of Atmospheric PCBs to Lake Michigan". Environmental Science & Technology. 39 (1): 57–63. Bibcode:2005EnST...39...57W. doi:10.1021/es048902d. PMID 15667075.

- ^ Jamshidi, Arsalan; Hunter, Stuart; Hazrati, Sadegh; Harrad, Stuart (2007). "Concentrations and Chiral Signatures of Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Outdoor and Indoor Air and Soil in a Major U.K. Conurbation". Environmental Science & Technology. 41 (7): 2153–2158. Bibcode:2007EnST...41.2153J. doi:10.1021/es062218c. PMID 17438756.

- ^ Faber, Harold (October 8, 1981). "Hunters who eat ducks warned on PCB hazard". New York Times.

- ^ Rapp Learn, Joshua (November 30, 2015). "Seabirds Are Dumping Pollution-Laden Poop Back on Land". Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ أ ب Richardson, Kristine L. (2011). "Biotransformation of 2,2′,5,5′-Tetrachlorobiphenyl (PCB 52) and 3,3′,4,4′-Tetrachlorobiphenyl (PCB 77) by Liver Microsomes from Four Species of Sea Turtles". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 24 (5): 718–725. doi:10.1021/tx1004562. PMID 21480586.

- ^ Forgue, S. T.; Preston, B. D.; Hargraves, W. A.; Reich, I. L.; Allen, J. R. (1979). "Direct evidence that an arene oxide is a metabolic intermediate of 2,2′,5,5′-tetrachlorobiphenyl". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 91 (2): 475–483. doi:10.1016/0006-291x(79)91546-8.

- ^ Parke, D. V. (1985). "The role of cytochrome P-450 in the metabolism of pollutants". Environmental Research. 17 (2–4): 97–100. doi:10.1016/0141-1136(85)90049-2.

- ^ McFarland, V. A.; Clarke, J. U. (1989). "Environmental occurrence, abundance, and potential toxicity of polychlorinated biphenyl congeners—Considerations for a congener-specific analysis". Environmental Health Perspectives. 81: 225–239. doi:10.1289/ehp.8981225. PMC 1567542. PMID 2503374.

- ^ Paterson, Gordon (2007). "PCB Elimination by Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens) during an Annual Temperature Cycle". Environmental Science & Technology. 41 (3): 824–829. Bibcode:2007EnST...41..824P. doi:10.1021/es060266r.

- ^ Hoekstra, Paul F. (2002). "Enantiomer-Specific Accumulation of PCB Atropisomers in the Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus)". Environmental Science & Technology. 36 (7): 1419–1425. Bibcode:2002EnST...36.1419H. doi:10.1021/es015763g.

- ^ Van den Berg, Martin; Birnbaum, Linda; Bosveld, Albertus T. C.; Brunström, Björn; Cook, Philip; et al. (1998). "Toxic Equivalency Factors (TEFs) for PCBs, PCDDs, PCDFs for Humans and Wildlife". Environmental Health Perspectives. 106 (12): 775–792. doi:10.1289/ehp.98106775. JSTOR 3434121. PMC 1533232. PMID 9831538.

- ^ أ ب Crinnion, Walter (March 2011). "Polychlorinated Biphenyls: Persistent Pollutants with Immunological, Neurological, and Endocrinological Consequences" (PDF). Environmental Medicine. 16 (1): 5–13. PMID 21438643. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ أ ب "Public Health Statement for Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs)". Toxic Substances Portal. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 3 March 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ Purdue University, EPA region 5 (n.d.). "Exploring the Great Lakes. Bioaccumulation/Biomagnification Effects" (PDF). EPA. p. 2. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Steingraber, Sandra (2001). "12". Having Faith : an ecologist's journey to motherhood (Berkley trade pbk. ed.). New York: Berkley. ISBN 978-0425189993.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةAoki, Yasunobu 2001 - ^ أ ب Aoki, Y. (2001). "Polychlorinated Biphenyls, Polychloronated Dibenzo-p-dioxins, and Polychlorinated Dibenzofurans as Endocrine Disrupters—What We Have Learned from Yusho Disease". Environmental Research. 86 (1): 2–11. Bibcode:2001ER.....86....2A. doi:10.1006/enrs.2001.4244. PMID 11386736.

- ^ Disease ID 8326 at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases

- ^ "PCB Baby Studies Part 2". www.foxriverwatch.comwww.foxriverwatch.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Environmental Diseases from A to Z". Archived from the original on 15 March 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jacobson, Joseph L.; Jacobson, Sandra W. (12 September 1996). "Intellectual Impairment in Children Exposed to Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Utero". New England Journal of Medicine. 335 (11): 783–789. doi:10.1056/NEJM199609123351104. PMID 8703183.قالب:Open Access

- ^ "Public Health Statement for PCBs". Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ Stewart, Paul; Reihman, Jacqueline; Lonky, Edward; Darvill, Thomas; Pagano, James (January 2000). "Prenatal PCB exposure and neonatal behavioral assessment scale (NBAS) performance". Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 22 (1): 21–29. doi:10.1016/S0892-0362(99)00056-2.

- ^ "PCBs: toxicity treatment and management". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, CDC. 1 September 2000.

- ^ Winneke, G. (September 2011). "Developmental aspects of environmental neurotoxicology: lessons from lead and polychlorinated biphenyls". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 308 (1–2): 9–15. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2011.05.020. PMID 21679971.

- ^ Schell, L. M. (March 2014). "Relationships of Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (p,p′-DDE) with Testosterone Levels in Adolescent Males". Environmental Health Perspectives. 122 (3): 304–9. doi:10.1289/ehp.1205984. PMC 3948020. PMID 24398050.

- ^ Hagmar, Lars; Rylander, Lars; Dyremark, Eva; Klasson-Wehler, Eva; Erfurth, Eva Marie (10 April 2001). "Plasma concentrations of persistent organochlorines in relation to thyrotropin and thyroid hormone levels in women". International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 74 (3): 184–188. doi:10.1007/s004200000213.

- ^ أ ب Lauby-Secretan, Béatrice; Loomis, Dana; Grosse, Yann; El Ghissassi, Fatiha; Bouvard, Veronique; Benbrahim-Tallaa, Lamia; Guha, Neela; Baan, Robert; Mattock, Heidi; Straif, Kurt; on behalf of the International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group, Lyon, France (March 15, 2013). "Carcinogenicity of polychlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated biphenyls". Lancet Oncology. 14 (4): 287–288. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70104-9. PMID 23499544.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kramer, Shira; Hikel, Stephanie Moller; Adams, Kristen; Hinds, David; Moon, Katherine (2012). "Current Status of the Epidemiologic Evidence Linking Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, and the Role of Immune Dysregulation". Environmental Health Perspectives. 120 (8): 1067–75. doi:10.1289/ehp.1104652. PMC 3440083. PMID 22552995.

- ^ United States. Toxic Substances Control Act. 15 U.S.C. § 2605. Approved October 11, 1976.

- ^ "Summary of the Toxic Substances Control Act". EPA. 2017-11-28.

- ^ Auer, Charles, Frank Kover, James Aidala, Marks Greenwood. “Toxic Substances: A Half Century of Progress.” EPA Alumni Association. March 2016.

- ^ "EPA Bans PCB Manufacture; Phases Out Uses". Press Release. EPA. 1979-04-19.

- ^ "Guidance on municipal waste strategies, Section 5.12 Equipment, which contains low volumes of PCBs" (PDF). UK Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions. 2001. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-14. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Qi, Zhifu (March 2014). "Effect of temperature and particle size on the thermal desorption of PCBs from contaminated soil". Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 21 (6): 4697–4704. doi:10.1007/s11356-013-2392-4. PMID 24352542.

- ^ Boate, Amy; Deleersnyder, Greg; Howarth, Jill; Mirabelli, Anita; Peck, Leanne (2004). "Chemistry of PCBs". Archived from the original on 2004-09-12. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)[نشر ذاتي سطري?] - ^ Woods, Sandra L.; Trobaugh, Darin J.; Carter, Kim J. (1999). "Polychlorinated Biphenyl Reductive Dechlorination by Vitamin B12s: Thermodynamics and Regiospecificity". Environmental Science & Technology. 33 (6): 857–863. Bibcode:1999EnST...33..857W. doi:10.1021/es9804823.

- ^ De Windt W, Aelterman P, Verstraete W (2005). "Bioreductive deposition of palladium (0) nanoparticles on Shewanella oneidensis with catalytic activity towards reductive dechlorination of polychlorinated biphenyls". Environmental Microbiology. 7 (3): 314–25. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00696.x. PMID 15683392.

- ^ Chun CL; Payne RB; Sowers KR; May HD (January 2003). "Electrical stimulation of microbial PCB degradation in sediment". Water Research. 47 (1): 141–152. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2012.09.038. PMC 3508379. PMID 23123087.

- ^ Cvančarová, M; Křesinová, Z; Filipová, A; Covino, S; Cajthaml, T (September 2012). "Biodegradation of PCBs by ligninolytic fungi and characterization of the degradation products". Chemosphere. 88 (11): 1317–1323. Bibcode:2012Chmsp..88.1317C. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.03.107. PMID 22546633.

وصلات خارجية

- ATSDR Toxicological Profile U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- IARC PCB Monograph

- PCBs at the US EPA

- National Toxicology Program technical reports searched for "PCB"

- Polychlorinated Byphenyls: Human Health Aspects by the WHO

- Current Intelligence Bulletin 7: Polychlorinated (PCBs)—NIOSH/CDC (1975)

- It's Your Health - PCBs (Health Canada)

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI

- CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list

- All articles with self-published sources

- Articles with self-published sources from May 2013

- ECHA InfoCard ID from Wikidata

- Articles containing unverified chemical infoboxes

- Chembox image size set

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from October 2015

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2010

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2013

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2015

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2016

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2015

- كلوروأرينات

- Flame retardants

- Endocrine disruptors

- ملوثات الهواء الخطرة

- IARC Group 2A carcinogens

- Soil contamination

- Synthetic materials

- Electric transformers

- Suspected testicular toxicants

- Suspected fetotoxicants

- Suspected female reproductive toxicants

- Persistent organic pollutants under the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution

- Persistent organic pollutants under the Stockholm Convention

- Monsanto

- Biphenyls

- Pollutants