گراپتوليت

| گراپتوليت | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cryptograptus from the Silurian of South America. Specimen at the Royal Ontario Museum | |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| أصنوفة غير معروفة (أصلحها): | الحياة |

| مملكة: | الحيوانية |

| شعبة: | نصف حبليات |

| صف: | †گراپتوليت Bronn, 1849 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

گراپتوليت Graptolithina، هي بقايا حيوانات مستحاثة منقرضة، عاشت في مستعمرات هيمنت على بحار حقب الحياة القديمة (الباليوزوي)، عاش بعضها طافياً وبعضها الآخر قاعياً. ظهرت في الدور الكمبري (منذ 545 ـ 490 مليون سنة) وانقرضت في الدور الفحمي (منذ 355ـ 300 مليون سنة). These filter-feeding organisms are known chiefly from fossils found from the Middle Cambrian (Miaolingian, Wuliuan) through the Lower Carboniferous (Mississippian).[3] A possible early graptolite, Chaunograptus, is known from the Middle Cambrian.[1] Recent analyses have favored the idea that the living pterobranch Rhabdopleura represents an extant graptolite which diverged from the rest of the group in the Cambrian.[2]

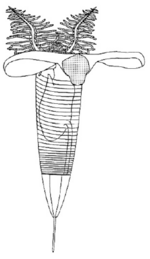

Fossil graptolites and Rhabdopleura share a colony structure of interconnected zooids housed in organic tubes (theca) which have a basic structure of stacked half-rings (fuselli). Most extinct graptolites belong to two major orders: the bush-like sessile Dendroidea and the planktonic, free-floating Graptoloidea. These orders most likely evolved from encrusting pterobranchs similar to Rhabdopleura. Due to their widespread abundance, planktonic lifestyle, and well-traced evolutionary trends, graptoloids in particular are useful index fossils for the Ordovician and Silurian periods.[4]

The name graptolite comes from the Greek graptos meaning "written", and lithos meaning "rock", as many graptolite fossils resemble hieroglyphs written on the rock. Linnaeus originally regarded them as 'pictures resembling fossils' rather than true fossils, though later workers supposed them to be related to the hydrozoans; now they are widely recognized as hemichordates.[4]

التسمية

قد اشتقت كلمة گراپتوليت من الكلمتين اليونانيتين graphein ومعناها «كتابة» وlithos (الحجر)؛ أي «كتابة على الحجر»، كناية عن انطباع آثارها على الصخور. والواقع أنه يسهل تعرّف انطباعات مستعمرات الغرابتوليتات على الصخور، إذ تتركّب هياكلها من الكولاجين، وهو بروتين معقّد يشبه في تركيبه الأظافر، يتحول غالباً في أثناء عملية الاستحاثة إلى مادة متفحمة أو إلى بيريت. وهي تتألف من مساكن تصطف بشكل خيط nema أو ساق stipe رفيعة أو متفرعة، كانت تسكنها حيوانات صغيرة (حييوينات zooïds) لم تُحفظ على شكل مستحاثات.

التصنيف

لقد حيَّر تصنيف الگراپتوليتات علماء المستحاثات، فقد صُنِّفَت في البداية مع الهيدريات Hydrozoa، غير أنها صنّفت فيما بعد مع صف جناحيات الغلاصم Pterobranchia نظراً لتشابه هياكلها مع هياكل هذه الأخيرة ولاكتشاف كوزلوفسكي R. Kozlowski ت(1938) مستحاثاتهما جنباً إلى جنب في طبقات حقب الباليوزوي الأسفل في بولونيا.

توجد هذه الهياكل كثيراً في الغَضار الصفحي والأردواز الأسود اللون بشكل انطباعات مضغوطة نتيجة ثقل الرواسب عليها، ولكنها نادرة الوجود وغير مضغوطة في بعض الصخور الكلسية والرملية.

إن غزارة الگراپتوليتات في صخور حقب الباليوزوي (حقب الحياة القديمة) وتوزعها الجغرافي الواسع ووجود أجناسها وأنواعها في أثناء فترة زمنية محدودة، تعطيها أهمية طبقية كبيرة. فهي تعدّ من المستحاثات المميّزة أوالمرشدة لبعض أدوار حقب الباليوزوي، وخاصة الدورين الأوردوفيشي والسيلوري (ماقبل490 ـ 410 مليون سنة).[5]

ينتمي صف الگراپتوليتات، مع صف جناحيات الغلاصم، إلى شعبة نصفيات الحبل. لكن سرعة تطوّر أفراد الغرابتوليتات أدت إلى تمييز رتب مختلفة عدة، أهمها رتبة دندروئيدا Dendroidea ورتبة گراپتولوئيدا Graptoloidea. نذكر من أجناس رتبة دندروئيدا الجنس ديكتيونيما الذي يميّز الفترة الواقعة ما بين الأوردوفيشي والكربوني (الفحمي)؛ ويُذكر من أجناس رتبة غرابتولوئيدا الجنس مونوگراپتوس الذي يميّز القسم الأعلى من السيلوري والجنس ديپلوگرابتوس ؛ الذي يميّز الفترة الواقعة ما بين الأوردوفيشي الأوسط والسيلوري الأسفل.

التاريخ

The name "graptolite" originates from the genus Graptolithus ("writing on the rocks"), which was used by Linnaeus in 1735 for inorganic mineralizations and incrustations which resembled actual fossils. In 1768, in the 12th volume of Systema Naturae, he included G. sagittarius and G. scalaris, respectively a possible plant fossil and a possible graptolite. In his 1751 Skånska Resa, he included a figure of a "fossil or graptolite of a strange kind" currently thought to be a type of Climacograptus (a genus of biserial graptolites).

Graptolite fossils were later referred to a variety of groups, including other branching colonial animals such as bryozoans ("moss animals") and hydrozoans. The term Graptolithina was established by Bronn in 1849, who considered them to represent orthoconic cephalopods. By the mid-20th century, graptolites were recognized as a unique group closely related to living pterobranchs in the genera Rhabdopleura and Cephalodiscus, which had been described in the late 19th century. Graptolithus, as a genus, was officially abandoned in 1954 by the ICZN.[6]

الگراپتوليت كدليل حفريات

المورفولوجيا

بنية المستعمرة

تتألّف المستعمرة في الجنس مونوگراپتوس، على سبيل المثال، من ساق أو خيط يحمل على أحد جانبيه سلسلة من التسنّنات الصغيرة، يمثِّل كل سن منها مسكناً صغيراً مخروطياً أو أسطوانياً، ينفتح للوسط الخارجي بفتحة تدعى فوهة المسكن، التي يختلف شكلها حسب الأجناس. فقد تكون مستديرة أو ذات شكل رباعي قد تحمل على محيطها أشواكاً. ويبدو أنّ المساكن التي كانت تحتلها الحيوانات الرخوة أو الحييوينات (أفراد المستعمرة الحية)، كانت متصلة بعضها ببعض بقناة محورية تمتد على طول الخيط.

يُشاهد في بداية الخيط، في النماذج جيدة الحفظ، مسكن كبير نسبياً، مخروطي الشكل قاعدته في الأسفل يدعى المسكن الجنيني، كان يسكنه أول فرد في المستعمرة. ينفتح هذا المسكن بفوهة متجهة نحو الأسفل، تحيط بها أشواك أو ينتهي بنتوء شوكي، وتُرى على سطحه خطوط عرضية.

وقد يأخذ خيط المستعمرة، في أجناس أخرى، أشكالاً مختلفة. فقد يكون ملتفاً أو متفرعاً إلى فرعين أو أكثر تتحد بداياتها بعضها مع بعض، وقد تتصل الفروع بعضها ببعض بوصلات مستعرضة تعطي المستعمرة شكلاً شبكياً، كما في الجنس ديكتيونما. وقد تصطف المساكن في المستعمرة على جانبي الخيط ، كما في الجنس ديپلوگرابتوس.

وقد أظهرت بعض النماذج النادرة والمحفوظة جيداً أن بعض مستعمرات الغرابتوليتات تتثبّت باستطالات من «خيوطها» وتتجمع على قرص مركزي متصل بكيس مملوء بالهواء، يبدو أنّه كان يقوم بعمل الـ «عوام» يساعد المستعمرات على العوم. كما أظهرت هذه النماذج وجود حويصلات صغيرة في الكيس الهوائي تحمل في داخلها المساكن الجنينية وتقوم بدور المناسل.

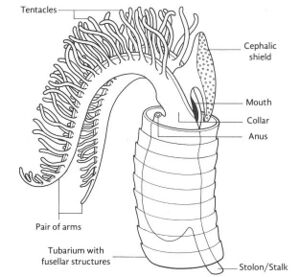

Zooids

A mature zooid has three important regions, the preoral disc or cephalic shield, the collar and the trunk. In the collar, the mouth and anus (U-shaped digestive system) and arms are found; Graptholitina has a single pair of arms with several paired tentacles. As a nervous system, graptolites have a simple layer of fibers between the epidermis and the basal lamina, also have a collar ganglion that gives rise to several nerve branches, similar to the neural tube of chordates.[7] Proper fossils of the soft parts of graptolites have yet to be found, and it is not known if they had pharyngeal gill slits or not,[8] but based on extant Rhabdopleura, it is likely that the grapotlite zooids had the same morphology.[4]

Taxonomy

Since the 1970s, as a result of advances in electron microscopy, graptolites have generally been thought to be most closely allied to the pterobranchs, a rare group of modern marine animals belonging to the phylum Hemichordata.[9] Comparisons are drawn with the modern hemichordates Cephalodiscus and Rhabdopleura. According to recent phylogenetic studies, rhabdopleurids are placed within the Graptolithina. Nonetheless, they are considered an incertae sedis family.[3]

On the other hand, Cephalodiscida is considered to be a sister subclass of Graptolithina. One of the main differences between these two groups is that Cephalodiscida species are not colonial organisms. In Cephalodiscida organisms, there is no common canal connecting all zooids. Cephalodiscida zooids have several arms, while Graptolithina zooids have only one pair of arms. Other differences include the type of early development, the gonads, the presence or absence of gill slits, and the size of the zooids. In the fossil record, where mostly tubaria (tubes) are preserved, it is complicated to distinguish between groups.

| Phylogeny of Pterobranchia[3] | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Graptolithina includes several minor families as well as two main extinct orders, Dendroidea (benthic graptolites) and Graptoloidea (planktic graptolites). The latter is the most diverse, including 5 suborders, where the most assorted is Axonophora (biserial graptolites, etc.). This group includes Diplograptids and Neograptids, groups that had great development during the Ordovician.[3] Old taxonomic classifications consider the orders Dendroidea, Tuboidea, Camaroidea, Crustoidea, Stolonoidea, Graptoloidea, and Dithecoidea but new classifications embedded them into Graptoloidea at different taxonomic levels.

Taxonomy of Graptolithina by Maletz (2014):[3][4]

Subclass Graptolithina Bronn, 1849

- Incertae sedis

- Family Rhabdopleuridae Harmer, 1905

- Family †Cysticamaridae Bulman, 1955

- Family †Wimanicrustidae Bulman, 1970

- Family †Dithecodendridae Obut, 1964

- Family †Cyclograptidae Bulman, 1938

- Order †Dendroidea Nicholson, 1872

- Family †Dendrograptidae Roemer, 1897 in Frech, 1897

- Family †Acanthograptidae Bulman, 1938

- Family †Mastigograptidae Bates & Urbanek, 2002

- Order †Graptoloidea Lapworth, 1875 in Hopkinson & Lapworth, 1875 (planktic graptolites)

- Suborder †Graptodendroidina Mu & Lin, 1981 in Lin (1981)

- Family †Anisograptidae Bulman, 1950

- Suborder †Sinograpta Maletz et al., 2009

- Family †Sigmagraptidae Cooper & Fortey, 1982

- Family †Sinograptidae Mu, 1957

- Family †Abrograptidae Mu, 1958

- Suborder †Dichograptina Lapworth, 1873

- Family †Dichograptidae Lapworth, 1873

- Family †Didymograptidae Mu, 1950

- Family †Pterograptidae Mu, 1950

- Family †Tetragraptidae Frech, 1897

- Suborder †Glossograptina Jaanusson, 1960

- Family †Isograptidae Harris, 1933

- Family †Glossograptidae Lapworth, 1873

- Suborder †Axonophora Frech, 1897 (biserial graptolites, and also retiolitids and monograptids)

- Infraorder †Diplograptina Lapworth, 1880

- Family †Diplograptidae Lapworth, 1873

- Subfamily †Diplograptinae Lapworth, 1873

- Subfamily †Orthograptinae Mitchell, 1987

- Family †Lasiograptidae Lapworth, 1880e

- Family †Climacograptidae Frech, 1897

- Family †Dicranograptidae Lapworth, 1873

- Subfamily †Dicranograptinae Lapworth, 1873

- Subfamily †Nemagraptinae Lapworth, 1873

- Family †Diplograptidae Lapworth, 1873

- Infraorder †Neograptina Štorch et al., 2011

- Family †Normalograptidae Štorch & Serpagli, 1993

- Family †Neodiplograptidae Melchin et al., 2011

- Subfamily †Neodiplograptinae Melchin et al., 2011

- Subfamily †Petalolithinae Bulman, 1955

- Superfamily †Retiolitoidea Lapworth, 1873

- Family †Retiolitidae Lapworth, 1873

- Subfamily †Retiolitinae Lapworth, 1873

- Subfamily †Plectograptinae Bouček & Münch, 1952

- Family †Retiolitidae Lapworth, 1873

- Superfamily †Monograptoidea Lapworth, 1873

- Family †Dimorphograptidae Elles & Wood, 1908

- Family †Monograptidae Lapworth, 1873

- Infraorder †Diplograptina Lapworth, 1880

- Suborder †Graptodendroidina Mu & Lin, 1981 in Lin (1981)

Ecology

Graptolites were a major component of the early Paleozoic ecosystems, especially for the zooplankton because the most abundant and diverse species were planktonic. Graptolites were most likely suspension feeders and strained the water for food such as plankton.[10]

Inferring by analogy with modern pterobranchs, they were able to migrate vertically through the water column for feeding efficiency and to avoid predators. With ecological models and studies of the facies, it was observed that, at least for Ordovician species, some groups of species are largely confined to the epipelagic and mesopelagic zone, from inshore to open ocean.[11] Living rhabdopleura have been found in deep waters in several regions of Europe and America but the distribution might be biased by sampling efforts; colonies are usually found as epibionts of shells.

Their locomotion was relative to the water mass in which they lived but the exact mechanisms (such as turbulence, buoyancy, active swimming, and so forth) are not clear yet. One proposal, put forward by Melchin and DeMont (1995), suggested that graptolite movement was analogous to modern free-swimming animals with heavy housing structures. In particular, they compared graptolites to "sea butterflies" (Thecostomata), small swimming pteropod snails. Under this suggestion, graptolites moved through rowing or swimming via an undulatory movement of paired muscular appendages developed from the cephalic shield or feeding tentacles. In some species, the thecal aperture was probably so restricted that the appendages hypothesis is not feasible. On the other hand, buoyancy is not supported by any extra thecal tissue or gas build-up control mechanism, and active swimming requires a lot of energetic waste, which would rather be used for the tubarium construction.[11]

There are still many questions regarding graptolite locomotion but all these mechanisms are possible alternatives depending on the species and its habitat. For benthic species, that lived attached to the sediment or any other organism, this was not a problem; the zooids were able to move but restricted within the tubarium. Although this zooid movement is possible in both planktic and benthic species, it is limited by the stolon but is particularly useful for feeding. Using their arms and tentacles, which are close to the mouth, they filter the water to catch any particles of food.[11]

Life cycle

The study of the developmental biology of Graptholitina has been possible by the discovery of the species R. compacta and R. normani in shallow waters; it is assumed that graptolite fossils had a similar development as their extant representatives. The life cycle comprises two events, the ontogeny and the astogeny, where the main difference is whether the development is happening in the individual organism or in the modular growth of the colony.

The life cycle begins with a planktonic planula-like larva produced by sexual reproduction, which later becomes the sicular zooid who starts a colony. In Rhabdopleura, the colonies bear male and female zooids but fertilized eggs are incubated in the female tubarium, and stay there until they become larvae able to swim (after 4–7 days) to settle away to start a new colony. Each larva surrounds itself in a protective cocoon where the metamorphosis to the zooid takes place (7–10 days) and attaches with the posterior part of the body, where the stalk will eventually develop.[4]

The development is indirect and lecithotrophic, and the larvae are ciliated and pigmented, with a deep depression on the ventral side.[12][7] Astogeny happens when the colony grows through asexual reproduction from the tip of a permanent terminal zooid, behind which the new zooids are budded from the stalk, a type of budding called monopodial. It is possible that in graptolite fossils the terminal zooid was not permanent because the new zooids formed from the tip of latest one, in other words, sympodial budding. These new organisms break a hole in the tubarium wall and start secreting their own tube.[4]

Graptolites in evolutionary development

In recent years, living graptolites have been used as a hemichordate model for Evo-Devo studies, as have their sister group, the acorn worms. For example, graptolites are used to study asymmetry in hemichordates, especially because their gonads tend to be located randomly on one side. In Rhabdopleura normani, the testicle is located asymmetrically, and possibly other structures such as the oral lamella and the gonopore.[13] The significance of these discoveries is to understand the early vertebrate left-right asymmetry due to chordates being a sister group of hemichordates, and therefore, the asymmetry might be a feature that developed early in deuterostomes. Since the location of the structures is not strictly established, also in some enteropneusts, it is likely that asymmetrical states in hemichordates are not under a strong developmental or evolutionary constraint. The origin of this asymmetry, at least for the gonads, is possibly influenced by the direction of the basal coiling in the tubarium, by some intrinsic biological mechanisms in pterobranchs, or solely by environmental factors.[13]

Hedgehog (hh), a highly conserved gene implicated in neural developmental patterning, was analyzed in Hemichordates, taking Rhabdopleura as a pterobranch representative. It was found that hedgehog gene in pterobranchs is expressed in a different pattern compared to other hemichordates as the enteropneust Saccoglossus kowalevskii. An important conserved glycine–cysteine–phenylalanine (GCF) motif at the site of autocatalytic cleavage in hh genes, is altered in R. compacta by an insertion of the amino acid threonine (T) in the N-terminal, and in S. kowalesvskii there is a replacement of serine (S) for glycine (G). This mutation decreases the efficiency of the autoproteolytic cleavage and therefore, the signalling function of the protein. It is not clear how this unique mechanism occurred in evolution and the effects it has in the group, but, if it has persisted over millions of years, it implies a functional and genetic advantage.[14]

Geological relevance

Preservation

Graptolites are common fossils and have a worldwide distribution. They are most commonly found in shales and mudrocks where sea-bed fossils are rare, this type of rock having formed from sediment deposited in relatively deep water that had poor bottom circulation, was deficient in oxygen, and had no scavengers. The dead planktic graptolites, having sunk to the sea floor, would eventually become entombed in the sediment and were thus well preserved.

These colonial animals are also found in limestones and cherts, but generally these rocks were deposited in conditions which were more favorable for bottom-dwelling life, including scavengers, and undoubtedly most graptolite remains deposited here were generally eaten by other animals.

Fossils are often found flattened along the bedding plane of the rocks in which they occur, though may be found in three dimensions when they are infilled by iron pyrite or some other minerals. They vary in shape, but are most commonly wiktionary:dendritic or branching (such as Dictyonema), sawblade-like, or "tuning fork"-shaped (such as Didymograptus murchisoni). Their remains may be mistaken for fossil plants by the casual observer, as it has been the case for the first graptolite descriptions.

Graptolites are normally preserved as a black carbon film on the rock's surface or as light grey clay films in tectonically distorted rocks. The fossil can also appear stretched or distorted. This is due to the strata that the graptolite is within, being folded and compacted. They may be sometimes difficult to see, but by slanting the specimen to the light they reveal themselves as a shiny marking. Pyritized graptolite fossils are also found.

A well-known locality for graptolite fossils in Britain is Abereiddy Bay, Dyfed, Wales, where they occur in rocks from the Ordovician Period. Sites in the Southern Uplands of Scotland, the Lake District and Welsh Borders also yield rich and well-preserved graptolite faunas. A famous graptolite location in Scotland is Dob's Linn with species from the boundary Ordovician-Silurian. Since the group had a wide distribution, fossils are also abundant in several parts of the United States, Canada, Australia, Germany and China, among others.

Stratigraphy

Graptolite fossils have predictable preservation, widespread distribution, and gradual change over a geologic time scale. This allows them to be used to date strata of rocks throughout the world.[9] They are important index fossils for dating Palaeozoic rocks as they evolved rapidly with time and formed many different distinctive species. Geologists can divide the rocks of the Ordovician and Silurian periods into graptolite biozones; these are generally less than one million years in duration. A worldwide ice age at the end of the Ordovician eliminated most graptolites except the neograptines. Diversification from the neograptines that survived the Ordovician glaciation began around 2 million years later.[15]

The Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (GOBE) influenced changes in the morphology of the colonies and thecae, giving rise to new groups like the planktic Graptoloidea. Later, some of the greatest extinctions that affected the group were the Hirnantian in the Ordovician and the Lundgreni in the Silurian, where graptolite populations were dramatically reduced (see also Lilliput effect).[4][16]

Graptolite diversity was greatly reduced during the Sedgwickii Event in the Aeronian.[17] This event has been attested in locations such as today's Canada, Libya as well as in La Chilca Formation of Argentina (then part of Gondwana).[17]

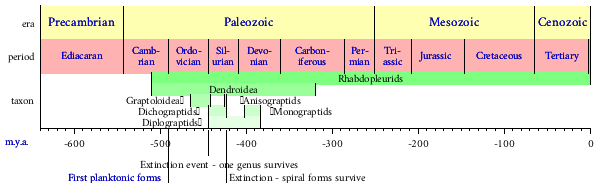

| |

| Ranges of Graptolite taxa. | |

الباحثون

The following is a selection of graptolite and pterobranch researchers:[4]

- Joachim Barrande (1799–1883)

- Hanns Bruno Geinitz (1814–1900)

- James Hall (1811–1898)

- Frederick M'Coy (1817–1899)

- Henry Alleyne Nicholson (1844–1899)

- John Hopkinson (1844–1919)

- Sven Leonhard Törnquist (1840–1920)

- Sven Axel Tullberg (1852–1886)

- Gerhard Holm (1853–1926)

- Carl Wiman (1867–1944)

- Thomas Sergeant Hall (1858–1915)

- Alexander Robert Keble (1884–1963)

- Noel Benson (1885–1957)

- William John Harris (1886–1957)

- David Evan Thomas (1902–1978)

- Mu Enzhi (1917–1987)

- Li Jijin (1928–2013)

- Vladimir Nikolayevich Beklemishev (1890–1962)

- Michael Sars (1805–1869)

- George Ossian Sars (1837–1927)

- William Carmichael M'Intosh (1838–1931)

- Nancy Kirk (1916–2005)

- Roman Kozłowski (1889–1977)

- Jörg Maletz

- Denis E. B. Bates

- Alfred C. Lenz

- Chris B. Cameron

- Adam Urbanek

- David K. Loydell

- Hermann Jaeger (1929–1992)

معرض الصور

See also

هوامش

- ^ أ ب Maletz, J. (2014). "Hemichordata (Pterobranchia, Enteropneusta) and the fossil record". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 398: 16–27. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.06.010.

- ^ أ ب Mitchell, C. E.; Melchin, M. J.; Cameron, C. B.; Maletz, J. (2013). "Phylogenetic analysis reveals that Rhabdopleura is an extant graptolite". Lethaia. 46 (1): 34–56. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2012.00319.x.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Maletz, Jörg (2014). "The classification of the Pterobranchia (Cephalodiscida and Graptolithina)". Bulletin of Geosciences. 89 (3): 477–540. doi:10.3140/bull.geosci.1465. ISSN 1214-1119.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Maletz, Jörg (2017). Graptolite Paleobiology. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781118515617.

- ^ فؤاد العجل. "الغرابتوليتات". الموسوعة العربية. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ^ Bulman, M. (1970) In Teichert, C. (ed.). Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part V. Graptolithina, with sections on Enteropneusta and Pterobranchia. (2nd Edition). Geological Society of America and University of Kansas Press, Boulder, Colorado and Lawrence, Kansas, XXXII + 163 pp.

- ^ أ ب Sato, A., Bishop, J. & Holland, P. (2008). Developmental Biology of Pterobranch Hemichordates: History and Perspectives. Genesis, 46:587-591.

- ^ Fundamentals of Invertebrate Palaeontology: Macrofossils

- ^ أ ب Fortey, Richard A. (1998). Life: A Natural History of the First Four Billion Years of Life on Earth. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 129.

- ^ "Graptolites". samnoblemuseum.ou.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ أ ب ت Cooper, R., Rigby, S., Loydell, D. & Bates, D. (2012) Palaeoecology of the Graptoloidea. Earth-Science Reviews, 112(1):23-41.

- ^ Röttinger, E. & Lowe, C. (2012) Evolutionary crossroads in developmental biology: hemichordates. Development, 139:2463-2475.

- ^ أ ب Sato, A. & Holland, P. (2008). Asymmetry in a Pterobranch Hemichordate and the Evolution of Left-Right Patterning. Developmental Dynamics, 237:3634 –3639)

- ^ Sato, A., White-Cooper, H., Doggett, K. & Holland, P. 2009. Degenerate evolution of the hedgehog gene in a hemichordate lineage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(18):7491-7494.

- ^ Bapst, D., Bullock, P., Melchin, M., Sheets, D. & Mitchell, C. (2012) Graptoloid diversity and disparity became decoupled during the Ordovician mass extinction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(9):3428-3433.

- ^ Urbanek, Adam (1993). "Biotic Crises in the History of Upper Silurian Graptoloids: A Palaeobiological Model". Historical Biology. 7 (1): 29–50. Bibcode:1993HBio....7...29U. doi:10.1080/10292389309380442.

- ^ أ ب Lopez, Fernando Enrique; Kaufmann, Cintia (2023). "New insights on the Silurian graptolite biostratigraphy of the La Chilca Formation, Poblete Norte section, Central Precordillera of San Juan, Argentina: faunal replacement and paleoenvironmental implications". Andean Geology. 50 (2): 201. doi:10.5027/andgeov50n2-3617.

المصادر

Bulman, 1970. In Teichert, C. (ed.). Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part V. Graptolithina , with sections on Enteropneusta and Pterobranchia. (2nd Edition). Geological Society of America and University of Kansas Press, Boulder, Colorado and Lawrence, Kansas, xxxii + 163 pp.

Jaroslav Kraft, Czech palaeontologist and a specialist in dendroid graptolites

وصلات خارجية

- Classification of the Cephalodiscoidea (Graptolithoidea) - Graptolite.net - Cephalodiscus

- BIG G - The British & Irish Graptolite Group - British and Irish Graptolite Group (BIG-G)

- What is a Graptolite? From the Research Website of David Bapst - What is a Graptolite?

- Graptolite photos Graptolites. retrieved 2012-02-10.

- Classification of the Graptolithoidea - Graptolites and Pterobranchs

- Podcast on Graptolites by David Bapst - Palaeocast

- Graptolites gallery by Michael P. Klimetz - Graptolites

- What are Fossil Graptolites and why are they useful in geology? - Youtube

- Writing on the rocks - Stephen Hui Geological Museum

- صفحات تستخدم خطا زمنيا

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Automatic taxobox cleanup

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages with empty portal template

- لافقاريات ما قبل التاريخ

- نصف حبليات

- گراپتوليتات

- Paleozoic invertebrates

- Cambrian invertebrates

- Carboniferous invertebrates

- Devonian invertebrates

- Ordovician invertebrates

- Permian invertebrates

- Silurian invertebrates

- Cambrian first appearances

- Carboniferous extinctions