نوناڤوت

Nunavut

ᓄᓇᕗᑦ (إينوكتيتوت) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| الشعار: ᓄᓇᕗᑦ ᓴᙱᓂᕗᑦ (Nunavut Sannginivut) "Our land, our strength" "Notre terre, notre force" | |

| الإحداثيات: 70°10′00″N 90°44′00″W / 70.16667°N 90.73333°W | |

| البلد | كندا |

| Confederation | 1 أبريل 1999 |

| العاصمة | Iqaluit |

| Largest city | Iqaluit |

| الحكومة | |

| • Commissioner | Rebekah Williams |

| • Premier | Joe Savikataaq (consensus government) |

| Legislature | Legislative Assembly of Nunavut |

| التمثيل الاتحادي | Parliament of Canada |

| المقاعد بمجلس العموم | 1 of 338 (0.3%) |

| المقاعد بمجلس الشيوخ | 1 of 105 (1%) |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 2٬038٬722 كم² (787٬155 ميل²) |

| • البر | 1٬877٬787 كم² (725٬018 ميل²) |

| • الماء | 160٬935 كم² (62٬137 ميل²) 7.9% |

| ترتيب المساحة | Ranked 1st |

| 20.4% of Canada | |

| التعداد (2016) | |

| • الإجمالي | 35٬944 [1] |

| • Estimate (2020 Q4) | 39٬285 [2] |

| • الترتيب | Ranked 12th |

| • الكثافة | 0٫02/km2 (0٫05/sq mi) |

| صفة المواطن | Nunavummiut Nunavummiuq (sing.)[3] |

| Official languages | English, French Inuit languages (Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun)[4] |

| GDP | |

| • Rank | 12th |

| • Total (2017) | C$2.846 billion[5] |

| • Per capita | C$58,452 (6th) |

| HDI | |

| • HDI (2018) | 0.908[6] — Very high (5th) |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC-07:00 (Mountain Time) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC-06:00 |

| UTC-06:00 (Central Time) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-05:00 |

| Southampton Island (Coral Harbour) | UTC-05:00 (Eastern Time) |

| UTC-05:00 (Eastern Time) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-04:00 |

| Postal abbr. | NU |

| Postal code prefix | |

| ISO 3166 code | CA-NU |

| Flower | Purple Saxifrage[7] |

| Tree | n/a |

| Bird | Rock Ptarmigan[8] |

| Rankings include all provinces and territories | |

نوناڤوت Nunavut /ˈnuːnəvʊt/ (from Inuktitut: ᓄᓇᕗᑦ أصد: [ˈnunavut]) يقع في الشمال الشرقي لكندا في جزيرة بافين, عاصمته كاليوت, مساحته مليونا كيلو متر مربع، ومع ذلك فسكانه 29.300 نسمة فقط، ينتشرون في 28 تجمعًا سكانيًّا مبعثرًا. بعد وقوع عدت اشتباكات سنة 1996 بين الجيش الكندي والإنويت, سكان المنطقة الاصليين, تقرر إعطاء المنطقة أكثر استقلالية فعليا سنة 1999.

الجغرافيا

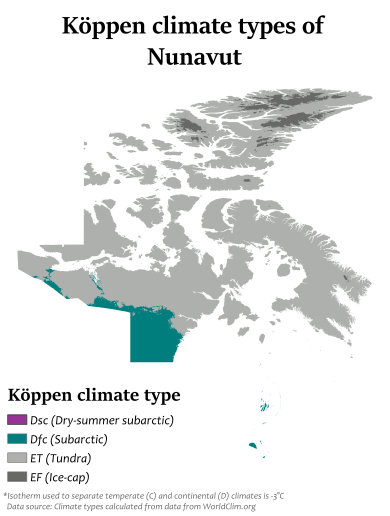

المناخ

Nunavut experiences a polar climate in most regions, owing to its high latitude and lower continental summertime influence than areas to the west. In more southerly continental areas, very cold subarctic climates can be found, due to July being slightly milder than the required 10 °C (50 °F).

| City | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | |

| Alert[9] | 6 | 1 | 43 | 33 | −29 | −36 | −20 | −33 |

| Baker Lake[10] | 17 | 6 | 63 | 43 | −28 | −35 | −18 | −31 |

| Cambridge Bay[11] | 13 | 5 | 55 | 41 | −29 | −35 | −19 | −32 |

| Eureka[12] | 9 | 3 | 49 | 37 | −33 | −40 | −27 | −40 |

| Iqaluit[13] | 12 | 4 | 54 | 39 | −23 | −31 | −9 | −24 |

| Kugluktuk[14] | 16 | 6 | 60 | 43 | −23 | −31 | −10 | −25 |

| Rankin Inlet[15] | 15 | 6 | 59 | 43 | −27 | −34 | −17 | −30 |

| أظهرClimate data for Iqaluit (Iqaluit Airport) WMO ID: 71909; coordinates 63°45′N 68°33′W / 63.750°N 68.550°W; elevation: 33.5 m (110 ft); 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1946–present |

|---|

السكان

Visible minority and indigenous identity (2016):[25][26]

As of the 2016 Canada Census, the population of Nunavut was 35,944, a 12.7% increase from 2011.[1] In 2006, 24,640 people identified as Inuit (83.6% of the total population), 100 as First Nations (0.3%), 130 as Métis (0.4%) and 4,410 as non-aboriginal (15.0%).[27]

| Municipality | 2016 | 2011 | 2006 | Growth 2011–16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iqaluit | 7,082 | 6,699 | 6,184 | 10.3% |

| Rankin Inlet | 2,441 | 1,905 | 1,528 | 28.1% |

| Arviat | 2,318 | 2,060 | 12.5% | |

| Baker Lake | 1,872 | 1,728 | 8.3% | |

| Cambridge Bay | 1,619 | 1,452 | 1,377 | 11.5% |

| Pond Inlet | 1,549 | 1,315 | 17.8% | |

| Igloolik | 1,454 | 1,538 | −5.5% | |

| Kugluktuk | 1,450 | 1,302 | 11.4% | |

| Pangnirtung | 1,425 | 1,325 | 7.5% | |

| Kinngait | 1,441 | 1,363 | 1,236 | 5.7% |

اللغة

Official languages are Inuit (Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun) sometimes called Inuktut,[28] English, and French.[4][29]

In his 2000 commissioned report (Aajiiqatigiingniq Language of Instruction Research Paper) to the Nunavut Department of Education, Ian Martin of York University said that a "long-term threat to Inuit languages from English is found everywhere, and current school language policies and practices on language are contributing to that threat" if Nunavut schools follow the Northwest Territories model. He provided a 20-year language plan to create a "fully functional bilingual society, in Inuktitut and English" by 2020.[30][needs update]

The plan provided different models, including:

- "Qulliq Model", for most Nunavut communities, with Inuktitut to be the main language of instruction.

- "Inuinnaqtun Immersion Model", for language reclamation and immersion to revitalize Inuinnaqtun as a living language.

- "Mixed Population Model", mainly for Iqaluit (possibly for Rankin Inlet), where the population is 40% Qallunaat, or non-Inuit, and may have different requirements.[31]

Of the 34,960 responses to the census question concerning "mother tongue" in the 2016 census, the most commonly reported languages in Nunavut were:

| Rank | Language | Number of respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inuktitut | 22,070 | 63.1% |

| 2 | English | 11,020 | 31.5% |

| 3 | French | 595 | 1.7% |

| 4 | Inuinnaqtun | 495 | 1.4% |

At the time of the census, only English and French were counted as official languages. Figures shown are for single-language responses and the percentage of total single-language responses.[32]

In the 2016 census it was reported that 2,045 people (5.8%) living in Nunavut had no knowledge of either official language of Canada (English or French).[33] The 2016 census also reported that of the 30,135 Inuit in Nunavut, 90.7% could speak either Inuktitut or Inuinnaqtun.[بحاجة لمصدر]

الدين

In 2011 census, Christianity constitutes 86% of Nunavut's population. About 13% of the population is non-religious, and 0.44% follows Aboriginal spirituality. There are small minorities of Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists and Jews.[34]

الاقتصاد

هذا section يحتاج المزيد من الأسانيد للتحقق. (March 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The economy of Nunavut is driven by the Inuit and Territorial Government, mining, oil, gas, and mineral exploration, arts, crafts, hunting, fishing, whaling, tourism, transportation, housing development, military, research, and education. Currently, one college operates in Nunavut, the Nunavut Arctic College, as well as several Arctic research stations located within the territory. The new Canadian High Arctic Research Station CHARS is planning for Cambridge Bay and high north Alert Bay Station.

Iqaluit hosts the annual Nunavut Mining Symposium every April,[35] a tradeshow that showcases the many economic activities ongoing in Nunavut.

التعدين

There are currently three major mines in operation in Nunavut. Agnico-Eagle Mines Ltd – Meadowbank Division. Meadowbank Gold Mine is an open pit gold mine with an estimated mine life 2010–2020 and employs 680 people.

The second recently opened mine in production is the Mary River Iron Ore mine operated by Baffinland Iron Mines. It is located close to Pond Inlet on North Baffin Island. They produce a high grade direct ship iron ore.

The most recent mine to open is Doris North or the Hope Bay Mine operated near Hope Bay Aerodrome by TMAC Resource Ltd. This new high grade gold mine is the first in a series of potential mines in gold occurrences all along the Hope Bay greenstone belt.

مشاريع التعدين

| Name | Company | In the region of | Material |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amaruq and Meliadine Gold Projects | Agnico-Eagle | Rankin Inlet | Gold |

| Back River Project | Sabina Gold & Silver Corp. | Bathurst Inlet | Gold |

| Izok Corridor Project | MMG Resources Inc. | Kugluktuk | Gold, Copper, Silver, Zinc |

| Hackett River | Glencore | Kugluktuk | Copper, Lead, Silver, Zinc |

| Chidliak | De Beers Canada | Iqaluit / Pangnirtung | Diamonds |

| Committee Bay, Three Bluffs Gold Project | Fury Gold Mines | Naujaat | Gold |

| Kiggavik | Areva Resources | Baker Lake | Uranium |

| Roche Bay | Advanced Exploration | Hall Beach | Iron Ore |

| Ulu, Lupin | Blue Star Gold, Elgin Mining Ltd. | Contwoyto Lake - connected to Yellowknife with an ice road | Gold |

| Storm Copper Property | Aston Bay Holdings | Taloyoak | Copper |

المناجم التاريخية

- Lupin Mine 1982–2005, gold, current owner Elgin Mining Ltd located near the Northwest Territories boundary near Contwoyto Lake)[36]

- Polaris Mine 1982–2002, lead and zinc (located on Little Cornwallis Island, not far from Resolute)

- Nanisivik Mine 1976–2002, lead and zinc, prior owner Breakwater Resources Ltd (near Arctic Bay) at Nanisivik

- Rankin Nickel Mine 1957–1962, nickel, copper and platinum group metals

- Jericho Diamond Mine 2006–2008, diamond (located 400 km, 250 mi, northeast of Yellowknife) 2012 produced diamonds from existing stockpile. No new mining; closed.

- Doris North Gold Mine Newmont Mining approx 3 km (2 mi) underground drifting/mining, none milled or processed. Newmont closed the mine and sold it to TMAC Resources in 2013. TMAC has now reached commercial production in 2017.

الطاقة

Nunavut's people rely primarily on diesel fuel[37] to run generators and heat homes, with fossil fuel shipments from southern Canada by plane or boat because there are few to no roads or rail links to the region.[38] There is a government effort to use more renewable energy sources,[39] which is generally supported by the community.[40]

This support comes from Nunavut feeling the effects of global warming.[41][42] Former Nunavut Premier Eva Aariak said in 2011, "Climate change is very much upon us. It is affecting our hunters, the animals, the thinning of the ice is a big concern, as well as erosion from permafrost melting."[38] The region is warming about twice as fast as the global average, according to the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

الحكم والسياسة

Nunavut has a Commissioner appointed by the federal Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs. As in the other territories, the commissioner's role is symbolic and is analogous to that of a Lieutenant-Governor.[43] While the Commissioner is not formally a representative of the Canadian monarch, a role roughly analogous to representing The Crown has accrued to the position.

Nunavut elects a single member of the House of Commons of Canada. This makes Nunavut the second largest electoral district in the world by area after Greenland. The current MP is Lori Idlout of the New Democratic Party.

The members of the unicameral Legislative Assembly of Nunavut are elected individually; there are no parties and the legislature is consensus-based.[44] The head of government, the premier of Nunavut, is elected by, and from the members of the legislative assembly. On June 14, 2018, Joe Savikataaq was elected as the Premier of Nunavut, after his predecessor Paul Quassa lost a non-confidence motion.[45][46] Former Premier Paul Okalik set up an advisory council of eleven elders, whose function it is to help incorporate "Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit" (Inuit culture and traditional knowledge, often referred to in English as "IQ") into the territory's political and governmental decisions.[47]

المناطق الإدارية

Nunavut is divided into three administrative regions, the Kitikmeot Region, the Kivalliq Region, and the Qikiqtaaluk Region

الرموز

The flag and the coat of arms of Nunavut were designed by Andrew Qappik from Pangnirtung.[48]

النزاع الإقليمي

A long-simmering dispute between Canada and the U.S. involves the issue of Canadian sovereignty over the Northwest Passage.[49]

الحكومة

انظر أيضاً

- Symbols of Nunavut

- Nunavut Arctic College

- Scouting and Guiding in Nunavut

- Nunatsiaq News

- Inuit Broadcasting Corporation

- Chemetco

- خليج كورونيشن

الهوامش

^1 Effective 12 November 2008.

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةcensus2016 - ^ "Population by year of Canada of Canada and territories". Statistics Canada. September 26, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ^ Nunavummiut, the plural demonym for residents of Nunavut, appears throughout the Government of Nunavut website Archived يناير 18, 2009 at the Wayback Machine, proceedings of the Nunavut legislature, and elsewhere. Nunavut Housing Corporation, Discussion Paper Released to Engage Nunavummiut on Development of Suicide Prevention Strategy. Alan Rayburn, previous head of the Canadian Permanent Committee of Geographical Names, opined that: "Nunavut is still too young to have acquired [a gentilé], although Nunavutan may be an obvious choice." In Naming Canada: stories about Canadian place names 2001. (2nd ed. ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. (ISBN 0-8020-8293-9); p. 50.

- ^ أ ب "Consolidation of (S.Nu. 2008, c.10) (NIF) Official Languages Act" (PDF). and "Consolidation of Inuit Language Protection Act" (PDF). Government of Nunavut. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "Gross domestic product, expenditure-based, provincial and territorial, annual (x 1,000,000)". Statistics Canada. 2019-09-21.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Subnational HDI - Global Data Lab". globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- ^ "The Official Flower of Nunavut: Purple Saxifrage". Legislative Assembly of Nunavut. 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^ "The Official Bird of Nunavut: The Rock Ptarmigan". Legislative Assembly of Nunavut. 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^ "Alert". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. September 25, 2013. Climate ID: 2400300. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Baker Lake A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. September 25, 2013. Climate ID: 2300500. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Cambridge Bay A *". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. September 25, 2013. Climate ID: 2400600. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Eureka A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. September 25, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ أ ب "Iqaluit A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. 31 October 2011. Climate ID: 2402590. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Kugluktuk A *". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. September 25, 2013. Climate ID: 2300902. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Rankin Inlet A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. September 25, 2013. Climate ID: 2303401. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "July 2008". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. 31 October 2011. Climate ID: 2402592. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "March 1999". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. 31 October 2011. Climate ID: 2402590. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "September 2010". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. 31 October 2011. Climate ID: 2402592. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "October 2015". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. 31 October 2011. Climate ID: 2402592. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "December 2010". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. 1 November 2019. Climate ID: 2402592. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "June 2019". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. 1 November 2019. Climate ID: 2402592. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ^ d.o.o, Yu Media Group. "Iqaluit, Canada - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2019-07-06.

- ^ "Météo climat stats for Iqaluit". Météo Climat. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ "Météo climat stats for Iqaluit". Météo Climat. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ "Aboriginal Peoples Highlight Tables". 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables". 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ "2006 Census Aboriginal Population Profiles". Statistics Canada. 2006. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- ^ "Nunavut Tunngavik calls for equitable funding for Inuit languages". CBC.

- ^ Your Linguistic Rights at the Office of the Language Commissioner of Nunavut

- ^ Ian Martin (December 2000). "Aajiiqatigiingniq Language of Instruction Research Paper" (PDF). p. i.

- ^ Board of Education (2000). "Summary of Aajiiqatigiingniq" (PDF). gov.nu.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 15, 2007. Retrieved October 27, 2007.

- ^ "Detailed Mother Tongue (186), Knowledge of Official Languages (5), Age Groups (17A) (3) (2006 Census)". Statistics Canada. December 7, 2010. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ Population by knowledge of official language, by province and territory (2006 Census) Archived يناير 15, 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Statistics Canada. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ^ "Religions in Canada—Census 2011". Statistics Canada/Statistique Canada. May 8, 2013.

- ^ "Travel". Nunavut Mining Symposium (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2018-06-17.

- ^ "Development projects". Wolfden Resources. أغسطس 31, 2007. Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ "Canada's North struggles to ditch diesel". Alberta Oil Magazine. Archived from the original on أكتوبر 4, 2013. Retrieved أبريل 3, 2013.

- ^ أ ب Van Loon, Jeremy (December 7, 2011). "Nunavut Region to Boost Renewable Power to Offset Climate Change". Bloomberg.

- ^ McDonald, N.C.; J.M. Pearce (2012). "Renewable Energy Policies and Programs in Nunavut: Perspectives from the Federal and Territorial Governments". Arctic. 65 (4): 465–475. doi:10.14430/arctic4244.

- ^ Nicole C. McDonald & Joshua M. Pearce, "Community Voices: Perspectives on Renewable Energy in Nunavut" Archived يوليو 9, 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Arctic 66(1), pp. 94–104 (2013).

- ^ Nunavut and Climate Change Archived أبريل 14, 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada

- ^ "Climate Change FAQ". Climate Change Nunavut. Archived from the original on يوليو 9, 2013.

- ^ "Nellie Kusugak named as new Nunavut commissioner". CBC News. June 23, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- ^ CBC Digital Archives (2006). "On the Nunavut Campaign Trail". CBC News. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

- ^ Weber, Bob (June 14, 2018). "After Paul Quassa ejected, Nunavut chooses deputy as new premier".

- ^ Frizell, Sara (June 14, 2018). "Joe Savikataaq is the new premier of Nunavut, after non-confidence vote ousts former leader". CBC News North.

- ^ "GN appoints IQ advisory council". Nunatsiaq Online. سبتمبر 12, 2003. Archived from the original on أبريل 10, 2017. Retrieved أبريل 9, 2017.

- ^ "The Coat of Arms of Nunavut". The Legislative Assembly of Nunavut. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "The US is picking a fight with Canada over a thawing Arctic shipping route". Quartz. 27 June 2019.

وصلات خارجية

- Nunavut Kavamat / Government of Nunavut: Official site

- نوناڤوت at the Open Directory Project

- Map showing regions of Nunavut (from Nunavut Government website)

- Legislative Assembly of Nunavut

- Nunavut Planning Commission

- Nunavut Tunngavik Inc.: Nunavut Land Claims website

- The Nunavut Act of 1993 at Canadian Legal Information Institute

- Nunavut K-12 bilingual language instruction plan: Martin, Ian. Aajiiqatigiingniq Language of Instruction Research Paper. Nunavut: Dept. of Education, 2000.

Tourism

Journalism

- CBC North Radio: hear Inuktitut and English radio from Nunavut

- Territorial newspaper reporting in Inuktitut and English, Nunatsiaq News

- Nunavut News from News/North

73°N 91°W / 73°N 91°W{{#coordinates:}}: لا يمكن أن يكون هناك أكثر من وسم أساسي واحد لكل صفحة

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "note"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="note"/>

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles containing فرنسية-language text

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- صفحات ذات وسوم إحداثيات غير صحيحة

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing إينوكتيتوت-language text

- Pages using infobox settlement with possible motto list

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- صفحات تستخدم جدول مستوطنة بقائمة محتملة لصفات المواطن

- Pages using infobox settlement with image map1 but not image map

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Wikipedia articles in need of updating from September 2020

- All Wikipedia articles in need of updating

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2018

- Articles needing additional references from March 2018

- All articles needing additional references

- نوناڤوت

- Inuit territories

- المحيط المتجمد الشمالي

- دول ومناطق تأسست في 1999

- مقاطعات وأقاليم كندا