الملك القرد

- هذا هو اسم صيني; لقب العائلة هو Sun.

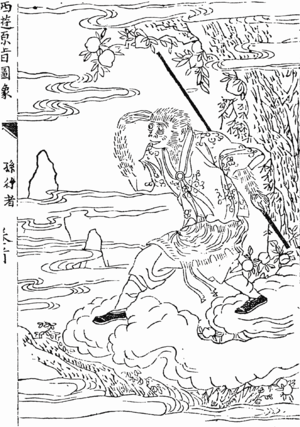

| Monkey King Sun Wukong | |

|---|---|

| شخصية | |

سون ووكونگ | |

| معلومات | |

| الجنس | Male |

| Birthplace | Flowers and Fruit Mountain |

| Source | Journey to the West, 16th century |

| Ability | Immortality, 72 Bian (Morphing Powers), Jin Dou Yun (Cloud Surfing), Jin Gang Bu Huai Zhi Shen (Superhuman Durability), Jin Jing Huo Yan (True Sight). |

| Weapon | Ruyi Jingu Bang/Ding Hai Shen Zhen |

| Master/Shifu/Gang Leader | Xuanzang |

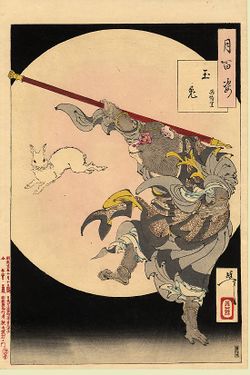

| سون ووكونگ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

سون ووكونگ depicted in Japanese Yoshitoshi's One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1889. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الصينية التقليدية | 孫悟空 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الحروف المبسطة | 孙悟空 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | Tôn Ngộ Không | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai | เห้งเจีย | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RTGS | [Heng Chia (من نطق لهجة هوكين "行者" (Hêng-chiá))] Error: {{Transliteration}}: transliteration text not Latin script (pos 12: م) (help) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 손오공 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | そん ごくう | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ملايو name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ملايو | Sun Gokong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| إندونيسية name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| إندونيسية | Sun Go Kong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

سون ووكونگ Sun Wukong، ويُعرف أيضاً بإسم الملك القرد Monkey King، هو شخصية أسطورية تظهر في عدد من الأساطير، يمكن تتبعها إلى فترة أسرة سونگ.[1] ويظهر كشخصية رئيسية في الرواية الكلاسيكية الصينية من القرن السادس عشر الرحلة إلى الغرب. كما يوجد سون ووكونگ في العديد من القصص والاستعارات اللاحقة. وفي الرواية، فهو قرد وُلِد من حـَجـَر اكتسب قوى فائقة عبر شعائر طاوية. وبعد أن تمرد على السماء وحبسه تحت جبل بقرار من البوذا، فإنه لاحقاً يصحب الراهب شوانزانگ في رحلة لاستعادة سوترات بوذية من الهند.

ويملك سون ووكونگ قوة خارقة؛ فهو قادر على رفع عصاه التي يبلغ وزنها 13,500 جين (7,960 كيلوجرام) بسهولة. كما أنه فائق السرعة، فهو قادر على السفر 108,000 لي (21,675 كم) في قفزة واحدة. (Note that this is more than half way around the world.) Sun knows 72 transformations, which allow him to transform into various animals and objects; however, he is troubled in transforming into other forms, due to the accompanying incomplete transformation of his tail. سون ووكونگ is a skilled fighter, capable of holding his own against the best warriors of heaven. Each of his hairs possess magical properties, capable of being transformed into clones of the Monkey King himself, and/or into various weapons, animals, and other objects. He knows spells to command wind, part water, conjure protective circles against demons, and freeze humans, demons, and gods alike.[2]

One of the most enduring Chinese literary characters, سون ووكونگ has a varied background and colorful cultural history. سون ووكونگ is considered by some scholars to be influenced by both the Hindu deity هانومان من رامايانا وعناصر الموروث الشعبي الصيني.[3][4][5]

التاريخ

One of the most enduring Chinese literary characters, the Monkey King has a varied background and colorful cultural history. His inspiration comes from an amalgam of Indian and Chinese culture. The Monkey King was influenced by the Hindu deity Hanuman from the Ramayana.[3][4][5], via stories passed by Buddhists who traveled to China. Monkey King's origin story includes the wind blowing on a stone, whereas Hanuman, the Hindu Monkey-God, is the son of the God of Wind. Some scholars believe the character may have originated from the first disciple of شوانزانگ, Shi Banto.[6]

His inspiration also comes from the White Monkey legends from the Chinese Chu kingdom (700–223 BC), which revered gibbons.[3] These legends gave rise to stories and art motifs during the Han dynasty, eventually contributing to the Monkey King figure. People in Fuzhou, China were worshipping Monkey Gods, long before the novel made the character a household name. There were 3 Monkey Saints of Lin Shui Palace, who were once Demons, being subdued by Empress Lin Shui Madam Chen Jing Gu. Dan Xia Da Sheng (丹霞大聖) - The Red Face Monkey Sage Tong Tian Da Sheng (通天大聖)- The Black Face Monkey Sage, Shuang Shuang San Lang (爽爽三聖) - The White Face Monkey Sage

The two traditional mainstream religions practiced in Fuzhou are Mahayana Buddhism and Taoism. Traditionally, many people practice both religions simultaneously. However, the origins of local religion dated back centuries. These diverse religions incorporated elements such as gods and doctrines from other religions and cultures, such as totem worship and traditional legends.[3] His religious status in Buddhism is often denied by Buddhist monks both Chinese and non-Chinese alike, but is very welcomed by the general public, spreading its name across the globe and establishing itself as a cultural icon.[3]

خلفية

المولد والنشأة

حواري تانگ سانزانگ

Five hundred years later, the Bodhisattva Guanyin searches for disciples to protect a pilgrim on a journey to the West to retrieve the Buddhist sutras. In the hearing of this, the Monkey King offers to serve the pilgrim, Tang Sanzang, a monk of the Tang dynasty, in exchange for his freedom after the pilgrimage is complete. Understanding Sun Wukong will be difficult to control, Guanyin gives Tang Sanzang a gift from the Buddha: a magical circlet which, once the Monkey King is tricked into putting it on, can never be removed. When Tang Sanzang chants a certain sutra, the band will tighten and cause an unbearable headache. To be fair, Guanyin gives the Monkey King three special hairs, only to be used in dire emergencies. Under Tang Sanzang's supervision, the Monkey King is allowed to journey to the West.

Throughout the novel, the Monkey King faithfully helps Tang Sanzang on his journey to India. They are joined by "Pigsy" (猪八戒 Zhu Bajie) and "Sandy" (沙悟浄 Sha Wujing), both of whom accompany the priest to atone for their previous crimes. Tang Sanzang's safety is constantly under threat from demons and other supernatural beings, as well as bandits. It is believed that by eating Tang Sanzang's flesh, one will obtain immortality and great power. The Monkey King often acts as his bodyguard to combat these threats. The group encounters a series of eighty-one tribulations before accomplishing their mission and returning safely to China. During the journey, the Monkey King learns about virtues and learns the teachings of Buddhism. There, the Monkey King attained Buddhahood, becoming the "Victorious Fighting Buddha" (Dòu-zhànshèng-fó (鬥戰勝佛)), for his service and strength.[2]

الأسماء والألقاب

Sun Wukong is known/pronounced as Suen Ng-hung in Cantonese, Son Gokū in Japanese, Son Oh Gong in Korean, Sun Ngō͘-Khong in Minnan, Tôn Ngộ Không in Vietnamese, Sung Ghokong or Sung Gokhong in Javanese, Sun Ngokong in Thai, "Wu Khone" in Arakanese and Sun Gokong in Malay and Indonesian.

Listed in the order that they were acquired:

- Shí Hóu (石猴)

- Meaning the "Stone monkey". This refers to his physical essence, being born from a sphere of rock after millennia of incubation on the Bloom Mountains/Flower-Fruit Mountain.

- Měi Hóuwáng (美猴王)

- Meaning "Handsome Monkey-King", or Houwang for short. The adjective Měi means "beautiful, handsome, pretty"; it also means "to be pleased with oneself", referring to his ego. Hóu ("monkey") also highlights his "naughty and impish" character.

- Sūn Wùkōng (孫悟空)

- The name given to him by his first master, Patriarch Bodhi (Subodh). The surname Sūn was given as an in-joke about the monkey, as monkeys are also called húsūn (猢猻), and can mean either a literal or a figurative "monkey" (or "macaque"). The surname sūn (孫) and the "monkey" sūn (猻) only differ in that the latter carries an extra "dog" (quǎn) radical to highlight that 猻 refers to an animal. The given name Wùkōng means "awakened to emptiness", sometimes translated as Aware of Vacuity.

- Bìmǎwēn (弼馬溫)

- The title of the keeper of the Heavenly Horses, a punning of bìmǎwēn (避馬瘟; lit. "avoiding the horses' plague"). A monkey was often put in a stable as people believed its presence could prevent the horses from catching the illness. Sun Wukong was given this position by the Jade Emperor after his first intrusion into Heaven. He was promised that it was a good position to have and that he, at least in this section, would be in the highest position. After discovering it was, in actuality, one of the lowest jobs in Heaven, he became angry, smashed the entire stable, set the horses free, and then quit. From then on, the title bìmǎwēn was used by his adversaries to mock him.

- Qítiān Dàshèng (齊天大聖)

- Meaning "The Great Sage, Heaven's Equal". Wùkōng took this title suggested to him by one of his demon friends, after he wreaked havoc in heaven people who heard of him called him Great Sage (Dàshèng, 大聖). The title originally holds no power, though it is officially a high rank. Later the title was granted the responsibility to guard the Heavenly Peach Garden, due to the Jade Emperor keeping him busy so he won't make trouble.

- Xíngzhě (行者)

- Meaning "ascetic", it refers to a wandering monk, a priest's servant, or a person engaged in performing religious austerities. Tang Sanzang calls Wukong Sūn-xíngzhě when he accepts him as his companion. This is pronounced in Japanese as gyōja (making him Son-gyōja).

- Dòu-zhànshèng-fó (鬥戰勝佛)

- "Victorious Fighting Buddha". Wukong was given this name once he ascended to Buddhahood at the end of the Journey to the West. This name is also mentioned during the traditional Chinese Buddhist evening services, specifically during the eighty-eight Buddha's repentance.

- Líng-míngdàn-hóu (靈明石猴)

- "Intelligent Stone Monkey". Wukong is revealed to be one of the four spiritual primates that do not belong to any of the ten categories that all beings in the universe are classified under. His fellow spiritual primates are the Six-Eared Macaque (六耳獼猴) (who is one of his antagonists in the main storyline), and the Red-Bottomed Horse Monkey (赤尻馬猴) & the Long-Armed Ape Monkey (通臂猿猴) (neither of who make actual appearances, only mentioned in passing by the Buddha), their powers and abilities all on par with each other.

- Sūn Zhǎnglǎo (孫長老)

- Zhǎnglǎo used as an honorific for a monk because Sun Wukong believed in Buddhism.

In addition to the names used in the novel, the Monkey King has other names in different languages:

- Kâu-chê-thian (猴齊天) in Minnan (Taiwan): "Monkey, Equal of Heaven".

- Maa5 lau1 zing1 (馬騮精) in Cantonese (Hong Kong and Guangdong): "Monkey Imp" (called by his enemies)

الخلود

Sun Wukong gained immortality through five different means, all of which stacked up to make him one of the most immortal and invincible beings.

Disciple to Subhuti

After feeling down about the future and death, Wukong sets out to find the immortal Taoist sage Subhuti to learn how to be immortal. There, Wukong learns spells to grasp all five elements and cultivate the way of immortality, as well as the 72 Earthly transformations. After seven years of training with the sage, Wukong gains immortality. It is noted that, technically, the Court of Heaven does not approve of this method of immortality.[7]

كتاب الموتى

In the middle of the night, Wukong's soul is tied up and dragged to the World of Darkness. He is informed there that his life in the human world has come to an end. In anger, Wukong fights his way through the World of Darkness to complain to "The Ten Kings", who are the judges of the dead. The Ten Kings try to address the complaint and calm Wukong by saying many people in the world have the same name and the fetchers of the dead may have gotten the wrong name. Wukong demands to see the register of life and death, then scribbles out his name, thus making him untouchable by the fetchers of death. It is because Wukong has learned magic/magical arts as a disciple to Subhuti that he can scare and demand the book of mortals from the Ten Kings and remove his name, thus making him even more immortal. After this incident, the Ten Kings complain to the Jade Emperor.[7]

خوخة الخلد

Soon after the Ten Kings complain to the Jade Emperor, the Court of Heaven appoints Sun Wukong as "Keeper of the Heavenly Horses," which is a fancy name for a stable boy. Angered by this, Wukong rebels and the Havoc in Heaven begins. During the Havoc in Heaven, Wukong is assigned to be the "Guardian of the Heavenly Peach Garden". The peach garden include three types of peaches, all of which grant over 3,000 years of life if only one is consumed. The first type blooms every three thousand years; anyone who eats it will become immortal, and their body will become both light and strong. The second type blooms every six thousand years; anyone who eats it will be able to fly and enjoy eternal youth. The third type blooms every nine thousand years; anyone who eats it will become "eternal as heaven and earth, as long-lived as the sun and moon". While serving as the guardian, Wukong does not hesitate to eat the peaches, thus granting him immortality and the abilities that come with the peaches. If Wukong had not been appointed as the Guardian of the Heavenly Peach Garden, he would not have eaten the Peaches of Immortality and gained another level of immortality.[7]

النبيذ السماوي

Because of Wukong's rebellious antics following his immortality after being a disciple to Subhuti and removing his name to the book of mortals, Wukong is not considered as an important celestial deity and is thus not invited to the Queen Mother of the West's royal banquet. After finding out that the Queen Mother of the West has not invited him to the royal banquet, which every other important deity was invited to, Wukong impersonates one of the deities that was invited and shows up early to see the deal with the banquet. He immediately gets distracted by the aroma of the wine and decides to steal and drink it. The heavenly wine also happens to have the ability to turn anyone who drinks it to an immortal.[7]

Pills of Longevity

While drunk from the heavenly wine from the royal banquet, Wukong stumbles into Laozi's alchemy lab, where he finds Laozi's pills of longevity, known as "The Immortals' Greatest Treasure." Filled with curiosity about the pills, Wukong eats a gourd of them. Those who eat the pills will become immortal. If Wukong had not been drunk from the heavenly wine, he would not have stumbled into Laozi's alchemy lab and eaten the pills of longevity.[7]

ما بعد الخلد

Following Wukong's three cause-and-effect methods of immortality during his time in heaven, he escapes back to his home at the Mountain of Flowers and Fruit. The Court of Heaven finds out what Wukong has done and a battle to capture Wukong ensues. Due to the five levels of immortality Wukong has achieved, his body has become nearly invincible and thus survives the multiple execution attempts by heaven. In the notable last execution, Wukong has placed inside Laozi's furnace in hopes that he will be distilled into the pills of the immortality elixir. Wukong survives 49 days of the samadhi fire in Laozi's furnace and gains the ability to recognize evil. In desperation, the court of heaven seeks help from Buddha, who finally imprisons Wukong under a mountain. Wukong's immortality and abilities ultimately come into use after Guanyin suggest him to be a disciple to Tang Sanzang in the Journey to the West. There, he protects Sanzang from the evil demons who try to eat Sanzang to gain immortality. Wukong's immortality protects him from the various ways the demons try to kill him, such as beheading, disemboweling, poisoning, boiling oil, and so on, none of which kill Wukong.[7] Sometime during the journey, Wukong and his companions obtain Man-fruit (人參果), a fruit even rarer and more powerful than the Peaches of Immortality, as only 30 of them will grow off one particular tree only found on the Longevity Mountain (萬壽山) every 10,000 years. While one smell can grant 360 years of life, consuming one will grant another 47,000 years of life.

التأثير

- Some scholars believe this character may have originated from the first disciple of Xuanzang, Shi Banto.[6]

- The Hindu deity Hanuman from the Ramayana is also considered by some scholars to be origin for Sun Wukong.[3]

- In The Shaolin Monastery (2008), Tel Aviv University Prof. Meir Shahar claims that Sun influenced a legend concerning the origins of the Shaolin staff method. The legend takes place during the Red Turban Rebellion of the Yuan dynasty. Bandits lay siege to the monastery, but it is saved by a lowly kitchen worker wielding a long fire poker as a makeshift staff. He leaps into the oven and emerges as a monstrous giant big enough to stand astride both Mount Song and the imperial fort atop Shaoshi Mountain (which are five miles apart). The bandits flee when they behold him. The Shaolin monks later realize that the kitchen worker was the Monastery's guardian deity, Vajrapani, in disguise. Shahar compares the worker's transformation in the stove with Sun Wukong's time in Laozi's crucible, their use of the staff, and the fact that Sun Wukong and his weapon can both grow to gigantic proportions.[8]

- Chinese DAMPE satellite is nicknamed after Wu Kong. The name could be understood as "understand the void" literally, relates to the undiscovered dark matter.[9]

انظر أيضاً

- List of media adaptations of الرحلة إلى الغرب

- عيد الملك القرد (إله)، الصين

- Birthday of the Monkey God

- Goku

المراجع

الهامش

- ^ Shahar, Meir (2008). The Shaolin monastery: History, religion, and the Chinese martial arts. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 9780824831103.

- ^ أ ب Journey to the West, Wu Cheng'en (1500-1582), Translated by Foreign Languages Press, Beijing 1993.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Hera S. Walker, "Indigenous or Foreign?: A Look at the Origins of the Monkey Hero Sun Wukong," Sino-Platonic Papers, 81 (September 1998)

- ^ أ ب Wendy Doniger. "Hanuman (Hindu mythology)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-02-22. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Doniger" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ أ ب Ramnath Subbaraman, "Beyond the Question of the Monkey Imposter: Indian Influence on the Chinese Novel The Journey to the West," Sino-Platonic Papers, 114 (March 2002) خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Subbaraman" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ أ ب "CCTV-大唐西游记". www.cctv.com.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Wu, Cheng−en (1982). Journey to the West. Translated by Jenner, William John Francis. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 0835110036.

- ^ Shahar, Meir. The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2008 (ISBN 0-8248-3110-1)

- ^ "China's new Monkey King set for journey into space". Xinhua. 2015-12-16. Retrieved 2017-11-27.

الملاحظات

<ref> بالاسم " Note01 " المحددة في <references> لها سمة المجموعة " Note " والتي لا تظهر في النص السابق.وصلات خارجية

- Sun Wukong Character Profile A detailed character profile of Sun Wukong, with character history, listing and explanations of his various names and titles, detailed information on his weapon, abilities, powers, and skills, and also a detailed explanation of his personality.

- Monkey King Thrice Beats White-Skeleton Demon

- Story of Sun Wukong with manhua

- Sun Wukong's entry at Godchecker is a tongue-in-cheek take on the Great Sage.

- (صينية) Journey to the West

- History of Monkey King with links to performances of Journey to the West by New York City's Official Storyteller

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with redirect hatnotes needing review

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles using Infobox character with multiple unlabeled fields

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Articles containing ڤيتنامية-language text

- Articles containing تايلندية-language text

- Transliteration template errors

- Articles containing كورية-language text

- Articles containing ملايو (لغة كبرى)-language text

- Articles containing إندونيسية-language text

- Literary characters

- Journey to the West characters

- Fictional religious workers

- Fictional shapeshifters

- Fictional monkeys

- Mythological monkeys

- Trickster gods

- Magic gods

- آلهة صينية

- Anthropomorphic martial artists

- أساطير صينية

- البوذية في الصين

- Fictional Buddhist monks

- Fictional characters who can change size

- Fictional characters who can duplicate themselves

- Fictional characters who use magic