الكلب وانعكاسه

The Dog and Its Reflection (or Shadow in later translations) is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 133 in the Perry Index.[1] The Greek language original was retold in Latin and in this way was spread across Europe, teaching the lesson to be contented with what one has and not to relinquish substance for shadow. There also exist Indian variants of the story. The morals at the end of the fable have provided both English and French with proverbs and the story has been applied to a variety of social situations.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The fable

A dog that is carrying a stolen piece of meat looks down as it is walking beside or crossing a stream and sees its own reflection in the water. Taking that for another dog carrying something better, it opens its mouth to attack the "other" and in doing so drops what it was carrying. An indication of how old and well-known this story was is given by an allusion to it in the work of the philosopher Democritus from the 5th century BCE. Discussing the foolish human desire for more, rather than being content with what one has, he describes it as being "like the dog in Aesop's fable".[2]

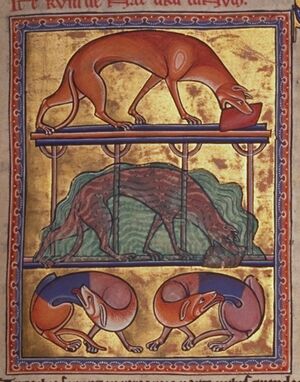

Many Latin versions of the fable also existed and eventually the story became incorporated into mediaeval animal lore. The Aberdeen Bestiary, written and illuminated in England around 1200 (see above), asserts that "If a dog swims across a river carrying a piece of meat or anything of that sort in its mouth, and sees its shadow, it opens its mouth and in hastening to seize the other piece of meat, it loses the one it was carrying".[3]

Versions

Although the outlines of the story remain broadly similar, certain details became modified over time. The fable was invariably referred to in Greek sources as "The dog carrying meat" after its opening words (Κύων κρέας φέρουσα), and the moral drawn there was to be contented with what one has.[4] Latin sources often emphasised the fact that the dog was taken in by its own reflection (simulacrum) in the water, with the additional moral of not being taken in by appearances.

Other words used to mean reflection have contributed to the alternative title of the fable, "The Dog and its Shadow". In the Latin versions of Walter of England,[5] Odo of Cheriton[6] and Heinrich Steinhöwel's Aesop,[7] for example, the word umbra is used. At that time it could mean both reflection and shadow, and it was the latter word that was preferred by William Caxton, who used Steinhöwel's as the basis of his own 1384 collection of the fables.[8] However, John Lydgate, in his retelling of the fable earlier in the century, had used "reflexion" instead.[9] In his French version of the story, La Fontaine gave it the title Le chien qui lâche sa proie pour l'ombre (The dog who relinquished his prey for its shadow VI.17),[10] where ombre has the same ambiguity of meaning.

Thereafter, and especially during the 19th century, the English preference was to use the word shadow in the fable's title. By this time, too, the dog is pictured as catching sight of himself in the water as he crosses a bridge. He is so represented in the painting by Paul de Vos in the Museo del Prado, dating from 1638/40,[11] and that by Edwin Henry Landseer, which is titled "The Dog and the Shadow" (1822), in the Victoria and Albert Museum.[12][13] Critics of La Fontaine had pointed out that the dog could not have seen its reflection if it had been paddling or swimming across the stream, as described in earlier sources, so crossing by a bridge would have been necessary for it to do so.[14] However, a bridge had already been introduced into the 12th-century Norman-French account of Marie de France[15] and Lydgate was later to follow her in providing that detail. Both also followed a version in which it is a piece of cheese rather than meat that the dog carries.

Indian analogues

A story close to Aesop's is inserted into the Buddhist scriptures as the Calladhanuggaha Jataka, where a jackal bearing a piece of flesh walks along a river bank and plunges in after the fish it sees swimming there. On returning from its unsuccessful hunt, the jackal finds a vulture has carried off its other prey.[16] A variation deriving from this is Bidpai's story of "The Fox and the Piece of Meat".[17] There a fox is on its way home with the meat when it catches sight of some chickens and decides to hunt one of them down; it is a kite that flies off with the meat it had left behind in this version.

Proverbial morals

In his retelling of the story, Lydgate had drawn the lesson that the one "Who all coveteth, oft he loseth all",[18] He stated as well that this was "an olde proverb"[19] which, indeed, in the form "All covet, all lose", was later to be quoted as the fable's moral by Roger L'Estrange.[20]

Jean de la Fontaine prefaced his version of the fable with the moral it illustrates before proceeding to a brief relation of the story. The point is not to be taken in by appearances, like the dog who attacks his reflection and falls into the water. As he struggles to swim to shore, he relaxes his grip on his plunder and loses "shadow and substance both".[21] An allusive proverb developed from the title: Lâcher sa proie pour l’ombre (giving up the prey for the shadow).

When this idiom was glossed in a dictionary of gallicisms, however, it was given the English translation, "to sacrifice the substance for the shadow",[22] which is based on the equally proverbial opposition between shadow and substance found in English versions of the fable. Aphra Behn, in summing up Francis Barlow's 1687 illustrated version of "The Dog and Piece of Flesh", coalesced the ancient proverb with the new:

- The wishing Curr growne covetous of all.

- To catch the Shadow letts the Substance fall.[23]

In Roger L'Estrange's relation of "The Dog and a Shadow", "He Chops at the Shadow and Loses the Substance"; Brooke Boothby, in his translation of the fables of Phaedrus, closes the poem of "The Dog and his Shadow" with the line "And shade and substance both were flown".[24] The allusive proverb is glossed as "Catch not at shadows and lose the substance" in a recent dictionary.[25]

One other author, Walter Pope in his Moral and political fables, ancient and modern (1698), suggested that the alternative proverb, "A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush", could be applied to the dog's poor judgment.[26]

Alternative applications

16th-century emblem books used illustrations in order to teach moral lessons through the picture alone, but sometimes found pictorial allusions to fables useful in providing a hint of their meaning. So in his Book of Emblemes (1586), the English poet Geoffrey Whitney gives to his illustration of the fable the Latin title Mediocribus utere partis (Make use of moderate possessions) and comments in the course of his accompanying poem,

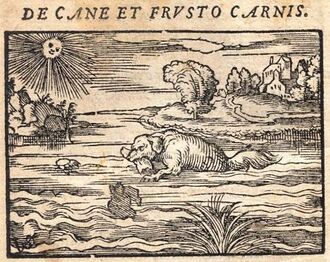

Others also treated the subject of being content with what one already has in an emblematic way. They include Latin versions of the fable by Gabriele Faerno, whose De Canis & Caro warns not to prefer the uncertain to the sure (Ne incerta certis anteponantur);[28] Hieronymus Osius, with his comment that the more some folk have, the more they want (Sunt, qui possideant cum plurima, plura requirunt);[29] and Arnold Freitag, who points out the stupidity of changing the sure for the uncertain (Stulta certi per incertum commutatio).[30] At a later date the financial implications of "throwing good money after bad" for uncertain gain were to be summed up in the English phrase "It was the story of the dog and the shadow".[31]

The fable was also capable of political applications as well. John Matthews adapted the fable into an attack on "the brain-sick Demagogues" of the French Revolution in pursuit of the illusion of freedom.[32] In a British context, during the agitation running up to the 1832 Reform Act, a pseudonymous 'Peter Pilpay' wrote a set of Fables from ancient authors, or old saws with modern instances in which appeared a topical retelling of "The Dog and the Shadow". Dedicated "to those who have something", it turned the fable's moral into a conservative appeal to stick to the old ways.[33] And in the following decade, a member of parliament who had given up his place in order to stand unsuccessfully for a more prestigious constituency was lampooned in the press as "most appropriately represented as the dog in the fable who, snatching at the shadow, lost the substance".[34]

It is under the title "The Dog and the Bone" that the fable was set by Scott Watson (b. 1964) as the third in his "Aesop's Fables for narrator and band" (1999).[35] More recently, the situation has been used to teach a psychological lesson by the Korean choreographer Hong Sung-yup. In his ballet "The Dog and the Shadow" (2013) the lost meat represents the accumulated memories which shape the personality.[36] That same year, the fable figured as the third movement of five in the young Australian composer Alice Chance's "Aesop’s Fables Suite" for viola da gamba.[37]

المراجع

- ^ See online

- ^ Geert van Dijk, Ainoi, logoi, mythoi: fables in archaic, classical, and Hellenistic Greek, Brill NL 1997, p.320

- ^ Aberdeen University Library MS 24, Folio 19v. The citation and accompanying illustration is available online

- ^ Francisco Rodríguez Adrados, History of the Graeco-latin Fable III, pp.174-8

- ^ Fable 5

- ^ Fable 61

- ^ Aesop p.50

- ^ Fable 1.5

- ^ Isopes Fabules (1310), stanza 135

- ^ WikiSource

- ^ Wiki Commons

- ^ V&A site

- ^ F.G. Stephens, Memoirs of Sir Edwin Landseer a Sketch of the Life of the Artist, London 1874, pp.76-7

- ^ Rue des fables

- ^ Mary Lou Martin, The Fables of Marie de France: An English Translation, "De cane et umbra", pp.44-5

- ^ Joseph Jacobs, The fables of Æsop, selected, told anew and their history traced, London, 1894, p.199

- ^ Maude Barrows Dutton, The Tortoise and the Geese and Other Fables of Bidpai, New York 1908, p.30

- ^ fable VII, line 3

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary Of English Proverbs (1949), p.36

- ^ Aesop’s Fables (1689), "A Dog and a Shadow", p.5

- ^ Norman Shapiro, The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine, Fable VI.17, p.146

- ^ Elisabeth Pradez, Dictionnaire des Gallicismes, Paris 1914, p.191

- ^ p.161

- ^ Fables and Satires (Edinburgh 1809), vol.1, p.7

- ^ Martin H. Manser, The Facts on File Dictionary of Proverbs, Infobase Publishing, 2007, p.416

- ^ "The Dog and Shadow", Fable 14

- ^ Emblem 39

- ^ Centum fabulae (1563), Fable 53

- ^ Fabulae Aesopi carmine elegiaco redditae (1564), poem 5

- ^ Mythologia Ethica (1579) pp.112-113

- ^ Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1868), p.366-7

- ^ Fables from La Fontaine, in English verse (1820), p.253

- ^ The Ten Pounder 1, Edinburgh 1832, pp.87-8

- ^ An Illustrative Key to the Political Sketches of H.B. (London, 1841), item 484, p.335

- ^ performance and score

- ^ Korea Herald, 12 June 2013

- ^ Carolyn McDowall, "Alice, a Young Composer – Taking a Chance on a Musical Life", The cultural concept circle, 29 May 2013

External links

Media related to The Dog and Its Reflection at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Dog and Its Reflection at Wikimedia Commons- 15th-20th century illustrations from books

- 17th-20th century French Prints