طاقة مائية

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| الطاقة المستدامة |

|---|

|

| حفظ الطاقة |

| الطاقة المتجددة |

| نقل مستدام |

|

|

الطاقة المائية Hydropower هي الطاقة المستمدة من حركة المياه المستمرة والتي لا يمكن ان تنفد. وهي من أهم مصادر الطاقة المتجددة، وبمعنى آخر هي الاستفادة من حركة المياه لأغراض مفيدة. فقد كان استخدام الطاقة المائية قبل أنتشار توفر الطاقة الكهربائية التجارية، وذلك في الري وطحن الحبوب، وصناعة النسيج، فضلا عن تشغيل المناشير.

تم استغلال طاقة المياه لـقرون طويلة. ففي امبراطورية روما، كانت الطاقة المائية تستخدم في مطاحن الدقيق وإنتاج الحبوب ، كما في الصين وبقية بلدان الشرق الاقصى، وتستخدم حركة الماء الهيدروليكية على تحريك عجلة لضخ المياه في قنوات الري وهو ما يعرف يالنواعير.

وفي الثلاثينات من القرن الثامن عشر ، في ذروة بناء القناة المائية استخدمت المياه للنقل الشاقولي صعودا ونزولا عبر التلال باستخدام السكك الحديدية.

كان نقل الطاقة الميكانيكية مباشرة يتطلب وجود الصناعات التي تستخدم الطاقة المائية قرب شلال. وخاصة خلال النصف الأخير من القرن التاسع عشر، واليوم يعتبر أهم استخدامات الطاقة المائية هو توليد الطاقة الكهربائية، مما يوفر الطاقة المنخفضة التكلفة حتى لو استخدمت في الأماكن البعيدة من المجرى المائي.

حساب كمية الطاقة المتاحة

A hydropower resource can be evaluated by its available power. Power is a function of the hydraulic head and volumetric flow rate. The head is the energy per unit weight (or unit mass) of water.[1] The static head is proportional to the difference in height through which the water falls. Dynamic head is related to the velocity of moving water. Each unit of water can do an amount of work equal to its weight times the head.

The power available from falling water can be calculated from the flow rate and density of water, the height of fall, and the local acceleration due to gravity:

- حيث

- (work flow rate out) is the useful power output (SI unit: watts)

- ("eta") is the efficiency of the turbine (dimensionless)

- is the mass flow rate (SI unit: kilograms per second)

- ("rho") is the density of water (SI unit: kilograms per cubic metre)

- is the volumetric flow rate (SI unit: cubic metres per second)

- is the acceleration due to gravity (SI unit: metres per second per second)

- ("Delta h") is the difference in height between the outlet and inlet (SI unit: metres)

To illustrate, the power output of a turbine that is 85% efficient, with a flow rate of 80 cubic metres per second (2800 cubic feet per second) and a head of 145 metres (476 feet), is 97 megawatts:[note 1]

Operators of hydroelectric stations compare the total electrical energy produced with the theoretical potential energy of the water passing through the turbine to calculate efficiency. Procedures and definitions for calculation of efficiency are given in test codes such as ASME PTC 18 and IEC 60041. Field testing of turbines is used to validate the manufacturer's efficiency guarantee. Detailed calculation of the efficiency of a hydropower turbine accounts for the head lost due to flow friction in the power canal or penstock, rise in tailwater level due to flow, the location of the station and effect of varying gravity, the air temperature and barometric pressure, the density of the water at ambient temperature, and the relative altitudes of the forebay and tailbay. For precise calculations, errors due to rounding and the number of significant digits of constants must be considered.[2]

Some hydropower systems such as water wheels can draw power from the flow of a body of water without necessarily changing its height. In this case, the available power is the kinetic energy of the flowing water. Over-shot water wheels can efficiently capture both types of energy.[3] The flow in a stream can vary widely from season to season. The development of a hydropower site requires analysis of flow records, sometimes spanning decades, to assess the reliable annual energy supply. Dams and reservoirs provide a more dependable source of power by smoothing seasonal changes in water flow. However, reservoirs have a significant environmental impact, as does alteration of naturally occurring streamflow. Dam design must account for the worst-case, "probable maximum flood" that can be expected at the site; a spillway is often included to route flood flows around the dam. A computer model of the hydraulic basin and rainfall and snowfall records are used to predict the maximum flood.[بحاجة لمصدر]

العيوب والمحدودية

Some disadvantages of hydropower have been identified. Dam failures can have catastrophic effects, including loss of life, property and pollution of land.

Dams and reservoirs can have major negative impacts on river ecosystems such as preventing some animals traveling upstream, cooling and de-oxygenating of water released downstream, and loss of nutrients due to settling of particulates.[4] River sediment builds river deltas and dams prevent them from restoring what is lost from erosion.[5][6] Furthermore, studies found that the construction of dams and reservoirs can result in habitat loss for some aquatic species.[7]

Large and deep dam and reservoir plants cover large areas of land which causes greenhouse gas emissions from underwater rotting vegetation. Furthermore, although at lower levels than other renewable energy sources,[بحاجة لمصدر] it was found that hydropower produces methane equivalent to almost a billion tonnes of CO2 greenhouse gas a year.[8] This occurs when organic matters accumulate at the bottom of the reservoir because of the deoxygenation of water which triggers anaerobic digestion.[9]

People who live near a hydro plant site are displaced during construction or when reservoir banks become unstable.[7] Another potential disadvantage is cultural or religious sites may block construction.[7][note 2]

التطبيقات

الطاقة الميكانيكية

طواحين الماء

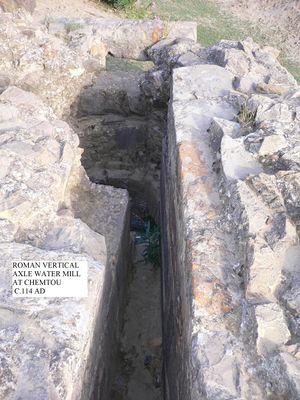

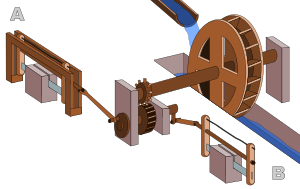

الطاحونة المائيةWatermill تبيّن تاريخياً أن منطقة حوض البحر المتوسط قد شهدت استخدام الطاحونة المائية في القرن الأول قبل الميلاد، وكان هناك نوعان من هذه الطواحين. ولا يزال النوع الأول قيد التشغيل حتى يومنا هذا في كل من إسكندنافيا والبلقان وبلدان الشرق الأدنى. وفيها يتم تركيب العجلة المائية أفقياً في أسفل الطاحونة بحيث يدور الطرف السفلي لمحورها الرأسي المصنوع من الحديد، داخل محمل من الحجارة الثقيلة (الصخرية منها). ويمر الطرف العلوي للمحور عبر فتحة في حجر الرحى السفلي ويتصل مباشرة بحجر الرحى العلوي، وبذلك تحتاج إلى مسننات لنقل الحركة. وتكون سرعة دوران حجر الرحى مماثلة لسرعة دوران العجلة المائية، وتدار الأخيرة بفعل الماء الهابط من علوّ من مجرى مياه جارية باستمرار.

ومنها اتخذ مبدأ العنفة الحديثة لتوليد الكهرباء من الماء. ويكون النوع الثاني من الطواحين المائية مماثلاً حيث يكون دفع الماء في الأعلى بدلاً من الأسفل. فشاع استخدام الطواحين المائية كثيراً في الوديان وقرب الأنهر فبلغت في أوروبا نحو 5624 طاحونة حوالي العام 1000م. ومع اختراع العجلة المائية والصناعات الحديثة ومن ثم المحركات تضاءل استخدام الطواحين المائية إذا لم نقل إنه قد انقرض.

| First Appearance of Various Industrial Mills in Medieval Europe, AD 770-1443 [12] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of mill | Date | Country | |||||||||

| Malt mill | 770 | France | |||||||||

| Fulling mill | 1080 | France | |||||||||

| Tanning mill | ca. 1134 | France | |||||||||

| Forge mill | ca. 1200 | England, France | |||||||||

| Tool-sharpening mill | 1203 | France | |||||||||

| Hemp mill | 1209 | France | |||||||||

| Bellows | 1269, 1283 | Slovakia, France | |||||||||

| Paper mill[13] | 1282 | Spain | |||||||||

| Sawmill | ca. 1300 | France | |||||||||

| Ore-crushing mill | 1317 | Germany | |||||||||

| Blast furnace | 1384 | France | |||||||||

| Cutting and slitting mill | 1443 | France | |||||||||

الهواء المضغوط

- النواعير إنگليزية: Waterwheels التي استخدمت لمئات من السنين في المطاحن وتسيير الآلات...الخ.

- الطاقة الكهرمائية إنگليزية: Hydroelectric energy، والمقصود هنا السدود والمنشآت النهرية التي تنتج الكهرباء.

- طاقة المد و الجزر إنگليزية: Tidal power، وهي استغلال طاقة المد والجزر في الاتجاه الأفقي.

- طاقة التيار المدي إنگليزية: Tidal stream power وهي استغلال طاقة المد والجزر في الاتجاه العمودي.

- طاقة الأمواج إنگليزية: Wave power التي تستخدم الطاقة على شكل موجات.

History

Ancient history

Evidence suggests that the fundamentals of hydropower date to ancient Greek civilization.[14] Other evidence indicates that the waterwheel independently emerged in China around the same period.[14] Evidence of water wheels and watermills date to the ancient Near East in the 4th century BC.[15] Moreover, evidence indicates the use of hydropower using irrigation machines to ancient civilizations such as Sumer and Babylonia.[7] Studies suggest that the water wheel was the initial form of water power and it was driven by either humans or animals.[7]

In the Roman Empire, water-powered mills were described by Vitruvius by the first century BC.[16] The Barbegal mill, located in modern-day France, had 16 water wheels processing up to 28 tons of grain per day.[17] Roman waterwheels were also used for sawing marble such as the Hierapolis sawmill of the late 3rd century AD.[18] Such sawmills had a waterwheel that drove two crank-and-connecting rods to power two saws. It also appears in two 6th century Eastern Roman sawmills excavated at Ephesus and Gerasa respectively. The crank and connecting rod mechanism of these Roman watermills converted the rotary motion of the waterwheel into the linear movement of the saw blades.[19]

Water-powered trip hammers and bellows in China, during the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), were initially thought to be powered by water scoops.[15] However, some historians suggested that they were powered by waterwheels. This is since it was theorized that water scoops would not have had the motive force to operate their blast furnace bellows.[20] Many texts describe the Hun waterwheel; some of the earliest ones are the Jijiupian dictionary of 40 BC, Yang Xiong's text known as the Fangyan of 15 BC, as well as Xin Lun, written by Huan Tan about 20 AD.[21] It was also during this time that the engineer Du Shi (c. AD 31) applied the power of waterwheels to piston-bellows in forging cast iron.[21]

Ancient Indian texts dating back to the 4th century BC refer to the term cakkavattaka (turning wheel), which commentaries explain as arahatta-ghati-yanta (machine with wheel-pots attached), however whether this is water or hand powered is disputed by scholars [22] India received Roman water mills and baths in the early 4th century AD when a certain according to Greek sources.[23] Dams, spillways, reservoirs, channels, and water balance would develop in India during the Mauryan, Gupta and Chola empires.[24][25][26]

Another example of the early use of hydropower is seen in hushing, a historic method of mining that uses flood or torrent of water to reveal mineral veins. The method was first used at the Dolaucothi Gold Mines in Wales from 75 AD onwards. This method was further developed in Spain in mines such as Las Médulas. Hushing was also widely used in Britain in the Medieval and later periods to extract lead and tin ores. It later evolved into hydraulic mining when used during the California Gold Rush in the 19th century.[27]

The Islamic Empire spanned a large region, mainly in Asia and Africa, along with other surrounding areas.[28] During the Islamic Golden Age and the Arab Agricultural Revolution (8th–13th centuries), hydropower was widely used and developed. Early uses of tidal power emerged along with large hydraulic factory complexes.[29] A wide range of water-powered industrial mills were used in the region including fulling mills, gristmills, paper mills, hullers, sawmills, ship mills, stamp mills, steel mills, sugar mills, and tide mills. By the 11th century, every province throughout the Islamic Empire had these industrial mills in operation, from Al-Andalus and North Africa to the Middle East and Central Asia.[30] Muslim engineers also used water turbines while employing gears in watermills and water-raising machines. They also pioneered the use of dams as a source of water power, used to provide additional power to watermills and water-raising machines.[31] Islamic irriguation techniques including Persian Wheels would be introduced to India, and would be combined with local methods, during the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire.[32]

Furthermore, in his book, The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, the Muslim mechanical engineer, Al-Jazari (1136–1206) described designs for 50 devices. Many of these devices were water-powered, including clocks, a device to serve wine, and five devices to lift water from rivers or pools, where three of them are animal-powered and one can be powered by animal or water. Moreover, they included an endless belt with jugs attached, a cow-powered shadoof (a crane-like irrigation tool), and a reciprocating device with hinged valves.[33]

19th century

In the 19th century, French engineer Benoît Fourneyron developed the first hydropower turbine. This device was implemented in the commercial plant of Niagara Falls in 1895 and it is still operating.[7] In the early 20th century, English engineer William Armstrong built and operated the first private electrical power station which was located in his house in Cragside in Northumberland, England.[7] In 1753, the French engineer Bernard Forest de Bélidor published his book, Architecture Hydraulique, which described vertical-axis and horizontal-axis hydraulic machines.[34]

The growing demand for the Industrial Revolution would drive development as well.[35] At the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in Britain, water was the main power source for new inventions such as Richard Arkwright's water frame.[36] Although water power gave way to steam power in many of the larger mills and factories, it was still used during the 18th and 19th centuries for many smaller operations, such as driving the bellows in small blast furnaces (e.g. the Dyfi Furnace) and gristmills, such as those built at Saint Anthony Falls, which uses the 50-foot (15 m) drop in the Mississippi River.[37][36]

Technological advances moved the open water wheel into an enclosed turbine or water motor. In 1848, the British-American engineer James B. Francis, head engineer of Lowell's Locks and Canals company, improved on these designs to create a turbine with 90% efficiency.[38] He applied scientific principles and testing methods to the problem of turbine design. His mathematical and graphical calculation methods allowed the confident design of high-efficiency turbines to exactly match a site's specific flow conditions. The Francis reaction turbine is still in use. In the 1870s, deriving from uses in the California mining industry, Lester Allan Pelton developed the high-efficiency Pelton wheel impulse turbine, which used hydropower from the high head streams characteristic of the Sierra Nevada.[بحاجة لمصدر]

20th century

The modern history of hydropower begins in the 1900s, with large dams built not simply to power neighboring mills or factories[39] but provide extensive electricity for increasingly distant groups of people. Competition drove much of the global hydroelectric craze: Europe competed amongst itself to electrify first, and the United States' hydroelectric plants in Niagara Falls and the Sierra Nevada inspired bigger and bolder creations across the globe.[40] American and USSR financers and hydropower experts also spread the gospel of dams and hydroelectricity across the globe during the Cold War, contributing to projects such as the Three Gorges Dam and the Aswan High Dam.[41] Feeding desire for large scale electrification with water inherently required large dams across powerful rivers,[42] which impacted public and private interests downstream and in flood zones.[43] Inevitably smaller communities and marginalized groups suffered. They were unable to successfully resist companies flooding them out of their homes or blocking traditional salmon passages.[44] The stagnant water created by hydroelectric dams provides breeding ground for pests and pathogens, leading to local epidemics.[45] However, in some cases, a mutual need for hydropower could lead to cooperation between otherwise adversarial nations.[46]

Hydropower technology and attitude began to shift in the second half of the 20th century. While countries had largely abandoned their small hydropower systems by the 1930s, the smaller hydropower plants began to make a comeback in the 1970s, boosted by government subsidies and a push for more independent energy producers.[42] Some politicians who once advocated for large hydropower projects in the first half of the 20th century began to speak out against them, and citizen groups organizing against dam projects increased.[47]

In the 1980s and 90s the international anti-dam movement had made finding government or private investors for new large hydropower projects incredibly difficult, and given rise to NGOs devoted to fighting dams.[48] Additionally, while the cost of other energy sources fell, the cost of building new hydroelectric dams increased 4% annually between 1965 and 1990, due both to the increasing costs of construction and to the decrease in high quality building sites.[49] In the 1990s, only 18% of the world's electricity came from hydropower.[50] Tidal power production also emerged in the 1960s as a burgeoning alternative hydropower system, though still has not taken hold as a strong energy contender.[51]

United States

Especially at the start of the American hydropower experiment, engineers and politicians began major hydroelectricity projects to solve a problem of 'wasted potential' rather than to power a population that needed the electricity. When the Niagara Falls Power Company began looking into damming Niagara, the first major hydroelectric project in the United States, in the 1890s they struggled to transport electricity from the falls far enough away to actually reach enough people and justify installation. The project succeeded in large part due to Nikola Tesla's invention of the alternating current motor.[52][53] On the other side of the country, San Francisco engineers, the Sierra Club, and the federal government fought over acceptable use of the Hetch Hetchy Valley. Despite ostensible protection within a national park, city engineers successfully won the rights to both water and power in the Hetch Hetchy Valley in 1913. After their victory they delivered Hetch Hetchy hydropower and water to San Francisco a decade later and at twice the promised cost, selling power to PG&E which resold to San Francisco residents at a profit.[54][55][56]

The American West, with its mountain rivers and lack of coal, turned to hydropower early and often, especially along the Columbia River and its tributaries. The Bureau of Reclamation built the Hoover Dam in 1931, symbolically linking the job creation and economic growth priorities of the New Deal.[57] The federal government quickly followed Hoover with the Shasta Dam and Grand Coulee Dam. Power demand in Oregon did not justify damming the Columbia until WWI revealed the weaknesses of a coal-based energy economy. The federal government then began prioritizing interconnected power—and lots of it.[58] Electricity from all three dams poured into war production during WWII.[59]

After the war, the Grand Coulee Dam and accompanying hydroelectric projects electrified almost all of the rural Columbia Basin, but failed to improve the lives of those living and farming there the way its boosters had promised and also damaged the river ecosystem and migrating salmon populations. In the 1940s as well, the federal government took advantage of the sheer amount of unused power and flowing water from the Grand Coulee to build a nuclear site placed on the banks of the Columbia. The nuclear site leaked radioactive matter into the river, contaminating the entire area.[60]

Post-WWII Americans, especially engineers from the Tennessee Valley Authority, refocused from simply building domestic dams to promoting hydropower abroad.[61][62] While domestic dam building continued well into the 1970s, with the Reclamation Bureau and Army Corps of Engineers building more than 150 new dams across the American West,[61] organized opposition to hydroelectric dams sparked up in the 1950s and 60s based on environmental concerns. Environmental movements successfully shut down proposed hydropower dams in Dinosaur National Monument and the Grand Canyon, and gained more hydropower-fighting tools with 1970s environmental legislation. As nuclear and fossil fuels grew in the 70s and 80s and environmental activists push for river restoration, hydropower gradually faded in American importance.[63]

أفريقيا

Foreign powers and IGOs have frequently used hydropower projects in Africa as a tool to interfere in the economic development of African countries, such as the World Bank with the Kariba and Akosombo Dams, and the Soviet Union with the Aswan Dam.[64] The Nile River especially has borne the consequences of countries both along the Nile and distant foreign actors using the river to expand their economic power or national force. After the British occupation of Egypt in 1882, the British worked with Egypt to construct the first Aswan Dam,[65] which they heightened in 1912 and 1934 to try to hold back the Nile floods. Egyptian engineer Adriano Daninos developed a plan for the Aswan High Dam, inspired by the Tennessee Valley Authority's multipurpose dam.

When Gamal Abdel Nasser took power in the 1950s, his government decided to undertake the High Dam project, publicizing it as an economic development project.[62] After American refusal to help fund the dam, and anti-British sentiment in Egypt and British interests in neighboring Sudan combined to make the United Kingdom pull out as well, the Soviet Union funded the Aswan High Dam.[66] Between 1977 and 1990 the dam's turbines generated one third of Egypt's electricity.[67] The building of the Aswan Dam triggered a dispute between Sudan and Egypt over the sharing of the Nile, especially since the dam flooded part of Sudan and decreased the volume of water available to them. Ethiopia, also located on the Nile, took advantage of the Cold War tensions to request assistance from the United States for their own irrigation and hydropower investments in the 1960s.[68] While progress stalled due to the coup d'état of 1974 and following 17-year-long Ethiopian Civil War Ethiopia began construction on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in 2011.[69]

Beyond the Nile, hydroelectric projects cover the rivers and lakes of Africa. The Inga powerplant on the Congo River had been discussed since Belgian colonization in the late 19th century, and was successfully built after independence. Mobutu's government failed to regularly maintain the plants and their capacity declined until the 1995 formation of the Southern African Power Pool created a multi-national power grid and plant maintenance program.[70] States with an abundance of hydropower, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Ghana, frequently sell excess power to neighboring countries.[71] Foreign actors such as Chinese hydropower companies have proposed a significant amount of new hydropower projects in Africa,[72] and already funded and consulted on many others in countries like Mozambique and Ghana.[71]

Small hydropower also played an important role in early 20th century electrification across Africa. In South Africa, small turbines powered gold mines and the first electric railway in the 1890s, and Zimbabwean farmers installed small hydropower stations in the 1930s. While interest faded as national grids improved in the second half of the century, 21st century national governments in countries including South Africa and Mozambique, as well as NGOs serving countries like Zimbabwe, have begun re-exploring small-scale hydropower to diversify power sources and improve rural electrification.[73]

أوروبا

In the early 20th century, two major factors motivated the expansion of hydropower in Europe: in the northern countries of Norway and Sweden high rainfall and mountains proved exceptional resources for abundant hydropower, and in the south coal shortages pushed governments and utility companies to seek alternative power sources.[74]

Early on, Switzerland dammed the Alpine rivers and the Swiss Rhine, creating, along with Italy and Scandinavia, a Southern Europe hydropower race.[75] In Italy's Po Valley, the main 20th century transition was not the creation of hydropower but the transition from mechanical to electrical hydropower. 12,000 watermills churned in the Po watershed in the 1890s, but the first commercial hydroelectric plant, completed in 1898, signaled the end of the mechanical reign.[76] These new large plants moved power away from rural mountainous areas to urban centers in the lower plain. Italy prioritized early near-nationwide electrification, almost entirely from hydropower, which powered their rise as a dominant European and imperial force. However, they failed to reach any conclusive standard for determining water rights before WWI.[77][76]

Modern German hydropower dam construction built off a history of small dams powering mines and mills going back to the 15th century. Some parts of Germany industry even relied more on waterwheels than steam until the 1870s.[78] The German government did not set out building large dams such as the prewar Urft, Mohne, and Eder dams to expand hydropower: they mostly wanted to reduce flooding and improve navigation.[79] However, hydropower quickly emerged as an added bonus for all these dams, especially in the coal-poor south. Bavaria even achieved a statewide power grid by damming the Walchensee in 1924, inspired in part by loss of coal reserves after WWI.[80]

Hydropower became a symbol of regional pride and distaste for northern 'coal barons', although the north also held strong enthusiasm for hydropower.[81] Dam building rapidly increased after WWII, this time with the express purpose of increasing hydropower.[82] However, conflict accompanied the dam building and spread of hydropower: agrarian interests suffered from decreased irrigation, small mills lost water flow, and different interest groups fought over where dams should be located, controlling who benefited and whose homes they drowned.[83]

شاهد أيضا

ملاحظات

- ^ Taking the density of water to be 1000 kilograms per cubic metre (62.5 pounds per cubic foot) and the acceleration due to gravity to be 9.81 metres per second per second.

- ^ See the World Commission on Dams (WCD) for international standards on the development of large dams.

المراجع

- ^ "Hydraulic head". Energy Education. 27 September 2021. Retrieved 8 Nov 2021.

Overall, hydraulic head is a way to represent the energy of stored a fluid - in this case water - per unit weight.

- ^ DeHaan, James; Hulse, David (10 February 2023). "Generator Power Measurements for Turbine Performance Testing at Bureau of Reclamation Powerplants" (PDF).

- ^ Sahdev, S. K. Basic Electrical Engineering. Pearson Education India. p. 418. ISBN 978-93-325-7679-7.

- ^ "How Dams Damage Rivers". American Rivers (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2021-11-25.

- ^ "As World's Deltas Sink, Rising Seas Are Far from Only Culprit". Yale E360 (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2021-11-25.

- ^ "Why the World's Rivers Are Losing Sediment and Why It Matters". Yale E360 (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2021-11-25.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Breeze, Paul (2018). Hydropower. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-812906-7.

- ^ "Hydroelectricity is a hidden source of methane emissions. These people want to solve that". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ Breeze, Paul (2019). Power Generation Technologies (3rd ed.). Oxford: Newnes. p. 116. ISBN 978-0081026311.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةطاحونة مائية Ritti, Grewe, Kessener 2007, 161 - ^ Wilson 1995, pp. 507f.; Wikander 2000, p. 377; Donners, Waelkens & Deckers 2002, p. 13

- ^ Adam Robert Lucas, 'Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds. A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe', Technology and Culture, Vol. 46, (Jan. 2005), pp. 1-30 (17).

- ^ Burns 1996, pp. 417f.

- ^ أ ب Munoz-Hernandez, German Ardul; Mansoor, Sa'ad Petrous; Jones, Dewi Ieuan (2013). Modelling and Controlling Hydropower Plants. London: Springer London. ISBN 978-1-4471-2291-3.

- ^ أ ب Reynolds, Terry S. (1983). Stronger than a Hundred Men: A History of the Vertical Water Wheel. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7248-0.

- ^ Oleson, John Peter (30 Jun 1984). Greek and Roman mechanical water-lifting devices: the history of a technology. Springer. p. 373. ISBN 90-277-1693-5. قالب:ASIN.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHill-2013 - ^ Greene, Kevin (1990). "Perspectives on Roman technology". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 9 (2): 209–219. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.1990.tb00223.x. S2CID 109650458.

- ^ Magnusson, Roberta J. (2002). Water Technology in the Middle Ages: Cities, Monasteries, and Waterworks after the Roman Empire. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801866265.

- ^ Lucas, Adam (2006). Wind, Water, Work: Ancient and Medieval Milling Technology. Leiden: Brill. p. 55.

- ^ أ ب Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 4: Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Cambridge University Press. p. 370. ISBN 0-521-05803-1.

- ^ Reynolds, p. 14 "On this basis, Joseph Needham suggested that the machine was a noria. Terry S. Reynolds, however, argues that the "term used in Indian texts is ambiguous and does not clearly indicate a water-powered device." Thorkild Schiøler argued that it is "more likely that these passages refer to some type of tread- or hand-operated water-lifting device, instead of a water-powered water-lifting wheel."

- ^ Wikander 2000, p. 400:

This is also the period when water-mills started to spread outside the former Empire. According to Cedrenus (Historiarum compendium), a certain Metrodoros who went to India in c. A.D. 325 "constructed water-mills and baths, unknown among them [the Brahmans] till then".

- ^ Christopher V. Hill (2008). South Asia: An Environmental History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-1-85109-925-2.

- ^ Jain, Sharad; Sharma, Aisha; Mujumdar, P. P. (2022), Evolution of Water Management Practices in India, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 325–349, doi:, ISBN 978-3-030-87066-9, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87067-6_18, retrieved on 2024-06-19

- ^ Singh, Pushpendra Kumar; Dey, Pankaj; Jain, Sharad Kumar; Mujumdar, Pradeep P. (2020-10-05). "Hydrology and water resources management in ancient India". Hydrology and Earth System Sciences (in English). 24 (10): 4691–4707. Bibcode:2020HESS...24.4691S. doi:10.5194/hess-24-4691-2020. ISSN 1027-5606.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Nakamura, Tyler, K.; Singer, Michael Bliss; Gabet, Emmanuel J. (2018). "Remains of the 19th Century: Deep storage of contaminated hydraulic mining sediment along the Lower Yuba River, California". Elem Sci Anth. 6 (1): 70. Bibcode:2018EleSA...6...70N. doi:10.1525/elementa.333.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hoyland, Robert G. (2015). In God's Path: The Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199916368.

- ^ al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (1976). "Taqī-al-Dīn and Arabic Mechanical Engineering. With the Sublime Methods of Spiritual Machines. An Arabic Manuscript of the Sixteenth Century". Institute for the History of Arabic Science, University of Aleppo: 34–35.

- ^ Lucas, Adam Robert (2005). "Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds: A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe". Technology and Culture. 46 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1353/tech.2005.0026. JSTOR 40060793. S2CID 109564224.

- ^ al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. "Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part II: Transmission Of Islamic Engineering". History of Science and Technology in Islam. Archived from the original on 18 February 2008.

- ^ Siddiqui

- ^ Jones, Reginald Victor (1974). "The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices by Ibn al-Razzaz Al-Jazari (translated and annotated by Donald R Hill)". Physics Bulletin. 25 (10): 474. doi:10.1088/0031-9112/25/10/040.

- ^ "History of Hydropower". US Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010.

- ^ "Hydroelectric Power". Water Encyclopedia.

- ^ أ ب Perkin, Harold James (1969). The Origins of Modern English Society, 1780-1880. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul PLC. ISBN 9780710045676.

- ^ Anfinson, John. "River of History: A Historic Resources Study of the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area". River Of History. National Park System. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Lewis, B J; Cimbala; Wouden (2014). "Major historical developments in the design of water wheels and Francis hydroturbines". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. IOP. 22 (1): 5–7. Bibcode:2014E&ES...22a2020L. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/22/1/012020.

- ^ Montrie, C., Water Power, Industrial Manufacturing, and Environmental Transformation in 19th-Century New England, https://energyhistory.yale.edu/units/water-power-industrial-manufacturing-and-environmental-transformation-19th-century-new-england, retrieved on 7 May 2022

- ^ Blackbourn, D (2006). The conquest of nature: water, landscape, and the making of modern Germany. Norton. pp. 217–18. ISBN 978-0-393-06212-0.

- ^ McCully, P (2001). Silenced rivers: the ecology and politics of large dams. Zed Books. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-1-85649-901-9.

- ^ أ ب McCully 2001, p. 227.

- ^ Blackbourn 2006, p. 222–24.

- ^ DamNation, Patagonia Films, Felt Soul Media, Stoecker Ecological, 2014

- ^ McCully 2001, p. 93.

- ^ Frey, F. (7 August 2020). "A Fluid Iron Curtain". Scandinavian Journal of History. Routledge. 45 (4): 506–526. doi:10.1080/03468755.2019.1629336. ISSN 0346-8755. S2CID 198611593.

- ^ D’Souza, R. (7 July 2008). "Framing India's Hydraulic Crisis: The Politics of the Modern Large Dam". Monthly Review. 60 (3): 112–124. doi:10.14452/MR-060-03-2008-07_7. ISSN 0027-0520.

- ^ Gocking, R. (June 2021). "Ghana's Bui Dam and the Contestation over Hydro Power in Africa". African Studies Review. Cambridge University Press. 64 (2): 339–362. doi:10.1017/asr.2020.41. S2CID 235747646.

- ^ McCully 2001, p. 274.

- ^ McCully 2001, p. 134.

- ^ Charlier, R. H. (1 December 2007). "Forty candles for the Rance River TPP tides provide renewable and sustainable power generation". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 11 (9): 2032–2057. Bibcode:2007RSERv..11.2032C. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2006.03.015. ISSN 1364-0321.

- ^ Berton, P (2009). Niagara: A History of the Falls. State University of New York Press. pp. 203–9. ISBN 978-1-4384-2930-4.

- ^ Berton 2009, p. 216.

- ^ Sinclair, B. (2006). "The Battle over Hetch Hetchy: America's Most Controversial Dam and the Birth of Modern Environmentalism (review)". Technology and Culture. Johns Hopkins University Press. 47 (2): 444–445. doi:10.1353/tech.2006.0153. ISSN 1097-3729. S2CID 110382607.

- ^ Hetch Hetchy, 2020, https://www.yosemite.com/hetch-hetchy/, retrieved on 8 May 2022

- ^ Blackbourn 2006, p. 218.

- ^ Lee, G., The Big Dam Era, https://energyhistory.yale.edu/units/big-dam-era, retrieved on 8 May 2022

- ^ White, R (1995). The Organic Machine. Hill and Wang. pp. 48–58. ISBN 978-0-8090-3559-5.

- ^ McCully 2001, p. 16.

- ^ White 1995, p. 71-72, 85, 89-111.

- ^ أ ب Lee, G., The Big Dam Era, https://energyhistory.yale.edu/units/big-dam-era, retrieved on 8 May 2022

- ^ أ ب Shokr, A. (2009). "Hydropolitics, Economy, and the Aswan High Dam in Mid-Century Egypt". The Arab Studies Journal. [Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, Arab Studies Journal, Arab Studies Institute]. 17 (1): 9–31. ISSN 1083-4753.

- ^ Lee, G., The End of the Big Dam Era, https://energyhistory.yale.edu/units/end-big-dam-era, retrieved on 8 May 2022

- ^ Gocking, R. (June 2021). "Ghana's Bui Dam and the Contestation over Hydro Power in Africa". African Studies Review. Cambridge University Press. 64 (2): 339–362. doi:10.1017/asr.2020.41. ISSN 1555-2462. S2CID 235747646.

- ^ Ross, C. (2017). Ecology and power in the age of empire: Europe and the transformation of the tropical world. Oxford University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0-19-182990-1.

- ^ Dougherty, J. E. (1959). "The Aswan Decision in Perspective". Political Science Quarterly. [Academy of Political Science, Wiley]. 74 (1): 21–45. doi:10.2307/2145939. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2145939.

- ^ McNeill, JR (2000). Something new under the sun: an environmental history of the twentieth-century world. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-0-393-32183-8.

- ^ Swain, A. (1997). "Ethiopia, the Sudan, and Egypt: The Nile River Dispute". The Journal of Modern African Studies. Cambridge University Press. 35 (4): 675–694. doi:10.1017/S0022278X97002577. ISSN 0022-278X. S2CID 154735027.

- ^ Gebreluel, G. (3 April 2014). "Ethiopia's Grand Renaissance Dam: Ending Africa's Oldest Geopolitical Rivalry?". The Washington Quarterly. Routledge. 37 (2): 25–37. doi:10.1080/0163660X.2014.926207. ISSN 0163-660X. S2CID 154203308.

- ^ Gottschalk, K. (3 May 2016). "Hydro-politics and hydro-power: the century-long saga of the Inga project". Canadian Journal of African Studies. Routledge. 50 (2): 279–294. doi:10.1080/00083968.2016.1222297. ISSN 0008-3968. S2CID 157111640.

- ^ أ ب Adovor Tsikudo, K. (2 January 2021). "Ghana's Bui Hydropower Dam and Linkage Creation Challenges". Forum for Development Studies. Routledge. 48 (1): 153–174. doi:10.1080/08039410.2020.1858953. ISSN 0803-9410. S2CID 232369055.

- ^ Gocking, R. (June 2021). "Ghana's Bui Dam and the Contestation over Hydro Power in Africa". African Studies Review. Cambridge University Press. 64 (2): 339–362. doi:10.1017/asr.2020.41. S2CID 235747646.

- ^ Klunne, Q. J. (1 August 2013). "Small hydropower in Southern Africa – an overview of five countries in the region". Journal of Energy in Southern Africa. 24 (3): 14–25. doi:10.17159/2413-3051/2013/v24i3a3138 (inactive 19 June 2024). ISSN 2413-3051.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of يونيو 2024 (link) - ^ Rodríguez, I. B. (30 December 2011). "¿Fue el sector eléctrico un gran beneficiario de «la política hidráulica» anterior a la Guerra Civil? (1911-1936)". Hispania. 71 (239): 789–818. doi:10.3989/hispania.2011.v71.i239.360. ISSN 1988-8368.

- ^ Blackbourn 2006, p. 217.

- ^ أ ب Parrinello, G. (2018). "Systems of Power: A Spatial Envirotechnical Approach to Water Power and Industrialization in the Po Valley of Italy, ca.1880–1970". Technology and Culture. Johns Hopkins University Press. 59 (3): 652–688. doi:10.1353/tech.2018.0062. ISSN 1097-3729. PMID 30245498. S2CID 52350633.

- ^ McNeill 2000, p. 174-175.

- ^ Blackbourn 2006, p. 198-207.

- ^ Blackbourn 2006, p. 212-213.

- ^ Landry, M. (2015). "Environmental Consequences of the Peace: The Great War, Dammed Lakes, and Hydraulic History in the Eastern Alps". Environmental History. [Oxford University Press, Forest History Society, American Society for Environmental History]. 20 (3): 422–448. doi:10.1093/envhis/emv053. ISSN 1084-5453.

- ^ Blackbourn 2006, p. 219.

- ^ Blackbourn 2006, p. 327.

- ^ Blackbourn 2006, p. 222-236.

المراجع الخارجية

- International Centre for Hydropower (ICH) hydropower portal with links to numerous organisations related to hydropower worldwide

- Practical Action (ITDG) a UK charity developing micro-hydro power and giving extensive technical documentation.

- National Hydropower Association

- British Hydropower Association

- microhydropower.net

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding Hydropower

- Hydro Quebec

- The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) Federal Agency that regulates more than 1500 hydropower dams in the United States.

- Hydropower Reform Coalition A U.S.-based coalition of more than 130 national, state, and local conservation and recreation groups that seek to protect and restore rivers affected by hydropower dams.

- Small Scale Hydro Power

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of يونيو 2024

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2014

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Articles with excerpts

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2021

- طاقة مائية

- تقنية

- طاقة

- طاقات بديلة

- طاقة متجددة

- المحافظة على البيئة