الشعوب الأصلية في البرازيل

شعوب أصلية من: Assurinis do Xingu , tapirapés , caiapós , tapirapés, ricbactas and bororos | |

| إجمالي التعداد | |

|---|---|

| 1,693,535 0.83% من تعداد البرازيل (2022 Census)[1] | |

| المناطق ذات التجمعات المعتبرة | |

| Predominantly in the North and Central-West | |

| اللغات | |

| Indigenous languages, Portuguese | |

| الدين | |

| Originally traditional beliefs and animism. 61.1% Roman Catholic, 19.9% Protestant, 11% non-religious, 8% other beliefs.[2] Animist religions still widely practiced by isolated populations | |

| الجماعات العرقية ذات الصلة | |

| Other indigenous peoples of the Americas |

Indigenous peoples once comprised an estimated 2000 tribes and nations inhabiting what is now the country of Brazil, before European contact around 1500.

At the time of European contact, some of the Indigenous people were traditionally semi-nomadic tribes who subsisted on hunting, fishing, gathering and migrant agriculture. Many tribes suffered extinction as a consequence of the European settlement and many were assimilated into the Brazilian population.

The Indigenous population was decimated by European diseases, declining from a pre-Columbian high of 2 to 3 million to some 300,000 اعتبارا من 1997[تحديث], distributed among 200 tribes. By the 2022 IBGE census, 1,693,535 Brazilians classified themselves as Indigenous, and the same census registered 274 indigenous languages of 304 different indigenous ethnic groups.[1][3]

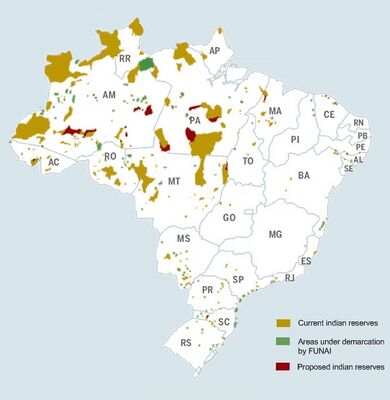

On 18 January 2007, FUNAI reported 67 remaining uncontacted tribes in Brazil, up from 40 known in 2005. With this addition Brazil passed New Guinea, becoming the country with the largest number of uncontacted peoples in the world.[4]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ

الأصول

Questions about the original settlement of the Americas have produced a number of hypothetical models. The origins of these Indigenous people are still a matter of dispute among archaeologists.[5]

الهجرة إلى القارتين

Anthropological and genetic evidence indicates that most Amerindian people descended from migrant peoples from Siberia and Mongolia who entered the Americas across the Bering Strait and along the western coast of North America in at least three separate waves. In Brazil, particularly, most native tribes who were living in the land by 1500 are thought to be descended from the first Siberian wave of migrants, who are believed to have crossed the Bering Land Bridge at the end of the last Ice Age, between 13,000 and 17,000 years before the present. A migrant wave would have taken some time after initial entry to reach present-day Brazil, probably entering the Amazon River basin from the Northwest. (The second and third migratory waves from Siberia, which are thought to have generated the Athabaskan, Aleut, Inuit, and Yupik people, apparently did not reach farther than the southern United States and Canada, respectively.)[6]

الدراسات الوراثية

Y-chromosome DNA

An analysis of Amerindian Y-chromosome DNA indicates specific clustering of much of the South American population. The micro-satellite diversity and distributions of the Y lineage specific to South America indicate that certain Amerindian populations have been isolated since the initial colonization of the region.[7]

Autosomal DNA

According to an autosomal DNA genetic study from 2012,[8] Native Americans descend from at least three main migrant waves from Siberia. Most of it is traced back to a single ancestral population, called 'First Americans'. However, those who speak Inuit languages from the Arctic inherited almost half of their ancestry from a second Siberia migrant wave. And those who speak Na-dene, on the other hand, inherited a tenth of their ancestry from a third migrant wave. The initial settling of the Americas was followed by a rapid expansion south down the coast, with little gene flow later, especially in South America. One exception to this is the Chibcha speakers, whose ancestry comes from both North and South America. [8]

mtDNA

Another study, focused on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), inherited only through the maternal line,[9] revealed that the maternal ancestry of the Indigenous people of the Americas traces back to a few founding lineages from Siberia, which would have arrived via the Bering strait. According to this study, the ancestors of Native Americans likely remained for a time near the Bering Strait, after which there would have been a rapid movement of settling of the Americas, taking the founding lineages to South America. According to a 2016 study, focused on mtDNA lineages, "a small population entered the Americas via a coastal route around 16.0 ka, following previous isolation in eastern Beringia for ~2.4 to 9 thousand years after separating from eastern Siberian populations. After rapidly spreading throughout the Americas, limited gene flow in South America resulted in a marked phylogeographic structure of populations, which persisted through time. All of the ancient mitochondrial lineages detected in this study were absent from modern data sets, suggesting a high extinction rate. To investigate this further, we applied a novel principal components multiple logistic regression test to Bayesian serial coalescent simulations. The analysis supported a scenario in which European colonization caused a substantial loss of pre-Columbian lineages".[10]

Linguistic comparison with Siberia

Linguistic studies have backed up genetic studies, with ancient patterns having been found between the languages spoken in Siberia and those spoken in the Americas.[11]

The Oceanic component in the Amazon region

Two 2015 autosomal DNA genetic studies confirmed the Siberian origins of the Natives of the Americas. However an ancient signal of shared ancestry with the Natives of Australia and Melanesia was detected among the Natives of the Amazon region. The migration coming out of Siberia would have happened 23,000 years ago.[12][13][14]

Archaeological remains

Brazilian native people, unlike those in Mesoamerica and the Andean civilizations, did not keep written records or erect stone monuments, and the humid climate and acidic soil have destroyed almost all traces of their material culture, including wood and bones. Therefore, what is known about the region's history before 1500 has been inferred and reconstructed from small-scale archaeological evidence, such as ceramics and stone arrowheads.

The most conspicuous remains of these societies are very large mounds of discarded shellfish (sambaquis) found in some coastal sites which were continuously inhabited for over 5,000 years; and the substantial "black earth" (terra preta) deposits in several places along the Amazon, which are believed to be ancient garbage dumps (middens). Recent excavations of such deposits in the middle and upper course of the Amazon have uncovered remains of some very large settlements, containing tens of thousands of homes, indicating a complex social and economic structure.[15]

Studies of the wear patterns of the prehistoric inhabitants of coastal Brazil found that the surfaces of anterior teeth facing the tongue were more worn than surfaces facing the lips, which researchers believe was caused by using teeth to peel and shred abrasive plants.[16]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ثقافة ماراجوارا

|

|

|

|

|

ثقافة ماراجوارا flourished on Marajó island at the mouth of the Amazon River.[17] Archeologists have found sophisticated pottery in their excavations on the island. These pieces are large, and elaborately painted and incised with representations of plants and animals. These provided the first evidence that a complex society had existed on Marajó. Evidence of mound building further suggests that well-populated, complex and sophisticated settlements developed on this island, as only such settlements were believed capable of such extended projects as major earthworks.[18]

The extent, level of complexity, and resource interactions of the Marajoara culture have been disputed. Working in the 1950s in some of her earliest research, American Betty Meggers suggested that the society migrated from the Andes and settled on the island. Many researchers believed that the Andes were populated by Paleoindian migrants from North America who gradually moved south after being hunters on the plains.

In the 1980s, another American archeologist, Anna Curtenius Roosevelt, led excavations and geophysical surveys of the mound Teso dos Bichos. She concluded that the society that constructed the mounds originated on the island itself.[19]

The pre-Columbian culture of Marajó may have developed social stratification and supported a population as large as 100,000 people.[17] The Native Americans of the Amazon rain forest may have used their method of developing and working in Terra preta to make the land suitable for the large-scale agriculture needed to support large populations and complex social formations such as chiefdoms.[17]

Xinguano Civilisation

The Xingu peoples built large settlements connected by roads and bridges, often bearing moats. The apex of their development was between 1200 CE to 1600 CE, their population inflating to the tens of thousands.[20]

Native people after the European colonisation

Distribution

On the eve of the Portuguese arrival in 1500, the coastal areas of Brazil had two major mega-groups – the Tupi (speakers of Tupi–Guarani languages), who dominated practically the entire length of the Brazilian coast, and the Tapuia (a catch-all term for non-Tupis, usually Jê language people), who resided primarily in the interior. The Portuguese arrived in the final days of a long pre-colonial struggle between Tupis and Tapuias, which had resulted in the defeat and expulsion of the Tapuias from most coastal areas.

Although the coastal Tupi were broken down into sub-tribes, frequently hostile to each other, they were culturally and linguistically homogeneous. The fact that the early Europeans encountered practically the same people and language all along the Brazilian coast greatly simplified early communication and interaction.

Coastal Sequence c. 1500 (north to south):[21]

- Tupinambá (Tupi, from the Amazon delta to Maranhão)

- Tremembé (Tapuia, coastal tribe, ranged from São Luis Island (south Maranhão) to the mouth of the Acaraú River in north Ceará; French traders cultivated an alliance with them)

- Potiguara (Tupi, literally "shrimp-eaters"; they had a reputation as great canoeists and aggressive expansionists, inhabited a great coastal stretch from Acaraú River to Itamaracá island, covering the modern states of southern Ceará, Rio Grande do Norte and Paraíba.)

- Tabajara (tiny Tupi tribe between Itamaracá island and Paraíba River; neighbors and frequent victims of the Potiguara)

- Caeté (Tupi group in Pernambuco and Alagoas, ranged from Paraíba River to the São Francisco River; after killing and eating a Portuguese bishop, they were subjected to Portuguese extermination raids and the remnant pushed into the Pará interior)

- Tupinambá again (Tupi par excellence, ranged from the São Francisco River to the Bay of All Saints, population estimated as high as 100,000; hosted Portuguese castaway Caramuru)

- Tupiniquim (Tupi, covered the Bahian discovery coast, from around Camamu to São Mateus River; these were the first indigenous people encountered by the Portuguese, having met the landing of captain Pedro Álvares Cabral in April 1500)

- Aimoré (Tapuia (Jê) tribe; concentrated on a sliver of coast in modern Espírito Santo state)

- Goitacá (Tapuia tribe; once dominated the coast from the São Mateus River (in Espírito Santo state) down to the Paraíba do Sul River (in Rio de Janeiro state); hunter-gatherers and fishermen, they were a shy people that avoided all contact with foreigners; estimated at 12,000; they had a fearsome reputation and were eventually annihilated by European colonists)

- Temiminó (small Tupi tribe, centered on Governador Island in Guanabara Bay; frequently at war with the Tamoio around them)

- Tamoio (Tupi, an old branch of the Tupinambá, ranged from the western edge of Guanabara Bay to Ilha Grande)

- Tupinambá again (Tupi, indistinct from the Tamoio. Inhabited the Paulist coast, from Ilha Grande to Santos; main enemies of the Tupiniquim to their west. Numbered between six and ten thousand).

- Tupiniquim again (Tupi, on the São Paulo coast from Santos/Bertioga down to Cananéia; aggressive expansionists, they were recent arrivals imposing themselves on the Paulist coast and the Piratininga plateau at the expense of older Tupinambá and Carijó neighbors; hosted Portuguese castaways João Ramalho ('Tamarutaca') and António Rodrigues in the early 1500s; the Tupiniquim were the first formal allies of the Portuguese colonists, helped establish the Portuguese Captaincy of São Vicente in the 1530s; sometimes called "Guaianá" in old Portuguese chronicles, a Tupi term meaning "friendly" or "allied")

- Carijó (Guarani (Tupi) tribe, ranged from Cananeia all the way down to Lagoa dos Patos (in Rio Grande do Sul state); victims of the Tupiniquim and early European slavers; they hosted the mysterious degredado known as the 'Bachelor of Cananeia')

- Charrúa (Tapuia (Jê) tribe in modern Uruguay coast, with an aggressive reputation against intruders; killed Juan Díaz de Solís in 1516)

With the exception of the hunter-gatherer Goitacases, the coastal Tupi and Tapuia tribes were primarily agriculturalists. The subtropical Guarani cultivated maize, tropical Tupi cultivated manioc (cassava), and highland Jês cultivated peanut, as the staple of their diet. Supplementary crops included beans, sweet potatoes, cará (yam), jerimum (pumpkin), and cumari (capsicum pepper).

Behind these coasts, the interior of Brazil was dominated primarily by Tapuia (Jê) people, although significant sections of the interior (notably the upper reaches of the Xingu, Teles Pires and Juruena Rivers – the area now covered roughly by modern Mato Grosso state) were the original pre-migration Tupi-Guarani homelands. Besides the Tupi and Tapuia, it is common to identify two other indigenous mega-groups in the interior: the Caribs, who inhabited much of what is now northwestern Brazil, including both shores of the Amazon River up to the delta and the Nuaraque group, whose constituent tribes inhabited several areas, including most of the upper Amazon (west of what is now Manaus) and also significant pockets in modern Amapá and Roraima states.

The names by which the different Tupi tribes were recorded by Portuguese and French authors of the 16th century are poorly understood. Most do not seem to be proper names, but descriptions of relationship, usually familial – e.g. tupi means "first father", tupinambá means "relatives of the ancestors", tupiniquim means "side-neighbors", tamoio means "grandfather", temiminó means "grandson", tabajara means "in-laws" and so on.[22] Some etymologists believe these names reflect the ordering of the migration waves of Tupi people from the interior to the coasts, e.g. first Tupi wave to reach the coast being the "grandfathers" (Tamoio), soon joined by the "relatives of the ancients" (Tupinamba), by which it could mean relatives of the Tamoio, or a Tamoio term to refer to relatives of the old Tupi back in the upper Amazon basin. The "grandsons" (Temiminó) might be a splinter. The "side-neighbors" (Tupiniquim) meant perhaps recent arrivals, still trying to jostle their way in. However, by 1870 the Tupi tribes' population had declined to 250,000 indigenous people and by 1890 had diminished to an approximate 100,000.

| Native Brazilian Population in Northeast Coast (Dutch estimates)[23] | |

|---|---|

| Period | Total |

| 1540 | +100,000 |

| 1640 | 9,000 |

First contacts

When the Portuguese explorers first arrived in Brazil in April 1500, they found, to their astonishment, a wide coastline rich in resources, teeming with hundreds of thousands of Indigenous people living in a "paradise" of natural riches. Pêro Vaz de Caminha, the official scribe of Pedro Álvares Cabral, the commander of the discovery fleet which landed in the present state of Bahia, wrote a letter to the King of Portugal describing in glowing terms the beauty of the land.

In "Histoire des découvertes et conquestes des Portugais dans le Nouveau Monde",[24] Lafiatau described the natives as people who wore no clothing but rather painted their whole bodies with red. Their ears, noses, lips and cheeks were pierced. The men would shave the front, the top of the head and over the ears, while the women would typically wear their hair loose or in braids. Both men and women would accessorize themselves with noisy porcelain collars and bracelets, feathers, and dried fruits. He describes the ritualistic nature of how they practiced cannibalism, and he even mentions the importance of the role of women in a household.

Before the arrival of the Europeans, the territory of current-day Brazil had an estimated population of between 1 and 11.25 million inhabitants.[25] During the first 100 years of contact, the Amerindian population was reduced by 90%. This was mainly due to disease and illness spread by the colonists, furthered by slavery and European-brought violence.[26] The indigenous people were traditionally mostly semi-nomadic tribes who subsisted on hunting, fishing, gathering, and migrant agriculture. For hundreds of years, the indigenous people of Brazil lived a semi-nomadic life, managing the forests to meet their needs. When the Portuguese arrived in 1500, the natives were living mainly on the coast and along the banks of major rivers. Initially, the Europeans saw native people as noble savages, and miscegenation of the population began right away. Portuguese claims of tribal warfare, cannibalism, and the pursuit of Amazonian brazilwood for its treasured red dye convinced the Portuguese that they should "civilize" the natives (originally, colonists called Brazil Terra de Santa Cruz, until later it acquired its name (see List of meanings of countries' names) from brazilwood). But the Portuguese, like the Spanish in their North American territories, had brought diseases with them against which many Amerindians were helpless due to lack of immunity. Measles, smallpox, tuberculosis, and influenza killed tens of thousands. The diseases spread quickly along the indigenous trade routes, and it is likely that whole tribes were annihilated without ever coming in direct contact with Europeans.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Slavery and the bandeiras

The mutual feeling of wonderment and a good relationship was to end in the succeeding years. The Portuguese colonists, all males, started to have children with female Amerindians, creating a new generation of mixed-race people who spoke Amerindian languages (a Tupi language called Nheengatu). The children of these Portuguese men and Amerindian women formed the majority of the population. Groups of fierce pathfinders organized expeditions called "bandeiras" (flags) into the backlands to claim them for the Portuguese crown and to look for gold and precious stones.

Intending to profit from the sugar trade, the Portuguese decided to plant sugar cane in Brazil, and to use indigenous slaves as the workforce, as the Spanish colonies were successfully doing. But the indigenous people were hard to capture. They were soon infected by diseases brought by the Europeans against which they had no natural immunity, and began dying in great numbers.

اليسوعيون

Jesuit priests arrived with the first Governor General as clerical assistants to the colonists, with the intention of converting the indigenous people to Catholicism. They presented arguments in support of the notion that the indigenous people should be considered human, and extracted a Papal bull (Sublimis Deus) proclaiming that, irrespective of their beliefs, they should be considered fully rational human beings, with rights to freedom and private property, who must not be enslaved.[27]

Jesuit priests such as fathers José de Anchieta and Manuel da Nóbrega studied and recorded their language and founded mixed settlements, such as São Paulo dos Campos de Piratininga, where colonists and Amerindians lived side by side, speaking the same Língua Geral (common language), and freely intermarried. They began also to establish more remote villages peopled only by "civilized" Amerindians, called Missions, or reductions (see the article on the Guarani people for more details).[28]

By the middle of the 16th century, Catholic Jesuit priests, at the behest of Portugal's monarchy, had established missions throughout the country's colonies. They worked to both Europeanize them and convert them to Catholicism. Some historians argue that the Jesuits provided a period of relative stability for the Amerindians.[27] Indeed, the Jesuits argued against using indigenous Brazilians for slave labour.[29] However, the Jesuits still contributed to European imperialism. Many historians regard Jesuit involvement to be an ethnocide of indigenous culture[30] where the Jesuits attempted to 'Europeanise' the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil.

In the mid-1770s, the indigenous peoples' fragile co-existence with the colonists was again threatened. Because of a complex diplomatic web between Portugal, Spain and the Vatican, the Jesuits were expelled from Brazil and the missions were confiscated and sold.[31]

By 1800, the population of Colonial Brazil had reached approximately 2.21 million, among whom only approximately 100,858 were indigenous. By 1850, that number had dwindled to an estimated 52,126 people, out of 1.86 million.[32]

Wars

A number of wars between several tribes, such as the Tamoio Confederation, and the Portuguese ensued, sometimes with the Amerindians siding with enemies of Portugal, such as the French, in the famous episode of France Antarctique in Rio de Janeiro, sometimes allying themselves to Portugal in their fight against other tribes. At approximately the same period, a German soldier, Hans Staden, was captured by the Tupinambá and released after a while. He described it in a famous book, Warhaftige Historia und beschreibung eyner Landtschafft der Wilden Nacketen, Grimmigen Menschfresser-Leuthen in der Newenwelt America gelegen (True Story and Description of a Country of Wild, Naked, Grim, Man-eating People in the New World, America) (1557)

There are various documented accounts of smallpox being knowingly used as a biological weapon by New Brazilian villagers that wanted to get rid of nearby Amerindian tribes (not always aggressive ones). The most "classical", according to Anthropologist, Mércio Pereira Gomes, happened in Caxias, in south Maranhão, where local farmers, wanting more land to extend their cattle farms, gave clothing owned by ill villagers (that normally would be burned to prevent further infection) to the Timbira. The clothing infected the entire tribe, and they had neither immunity nor cure. Similar things happened in other villages throughout South America.[33]

The rubber trade

The 1840s brought trade and wealth to the Amazon. The process for vulcanizing rubber was developed, and worldwide demand for the product skyrocketed. The best rubber trees in the world grew in the Amazon, and thousands of rubber tappers began to work the plantations. When the Amerindians proved to be a difficult labor force, peasants from surrounding areas were brought into the region. In a dynamic that continues to this day, the indigenous population was at constant odds with the peasants, who the Amerindians felt had invaded their lands in search of treasure.

The legacy of Cândido Rondon

In the 20th century, the Brazilian Government adopted a more humanitarian attitude and offered official protection to the indigenous people, including the establishment of the first indigenous reserves. Fortune brightened for the Amerindians around the turn of the 20th century when Cândido Rondon, a man of both Portuguese and Bororo ancestry, and an explorer and progressive officer in the Brazilian army, began working to gain the Amerindians' trust and establish peace. Rondon, who had been assigned to help bring telegraph communications into the Amazon, was a curious and natural explorer. In 1910, he helped found the Serviço de Proteção aos Índios – SPI (Service for the Protection of Indians, today the FUNAI, or Fundação Nacional do Índio, National Foundation for Indians). SPI was the first federal agency charged with protecting Amerindians and preserving their culture. In 1914, Rondon accompanied Theodore Roosevelt on Roosevelt's famous expedition to map the Amazon and discover new species. During these travels, Rondon was appalled to see how settlers and developers treated the indigenes, and he became their lifelong friend and protector.

Rondon, who died in 1958, is a national hero in Brazil. The Brazilian state of Rondônia is named after him.

SPI failure and FUNAI

After Rondon's pioneering work, the SPI was turned over to bureaucrats and military officers and its work declined after 1957. The new officials did not share Rondon's deep commitment to the Amerindians. SPI sought to address tribal issues by transforming the tribes into mainstream Brazilian society. The lure of reservation riches enticed cattle ranchers and settlers to continue their assault on Amerindians' lands – and the SPI eased the way. Between 1900 and 1967, an estimated 98 indigenous tribes were wiped out.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Mostly due to the efforts of the Villas-Bôas brothers, Brazil's first Indian reserve, the Xingu National Park, was established by the Federal Government in 1961.

During the social and political upheaval in the 1960s, reports of mistreatment of Amerindians increasingly reached Brazil's urban centers and began to affect Brazilian thinking. In 1967, following the publication of the Figueiredo Report, commissioned by the Ministry of the Interior, the military government launched an investigation into SPI. It soon came to light that the SPI was corrupt and failing to protect natives, their lands and culture. The 5,000-page report catalogued atrocities including slavery, sexual abuse, torture, and mass murder.[34] It has been charged that agency officials, in collaboration with land speculators, were systematically slaughtering the Amerindians by intentionally circulating disease-laced clothes.[بحاجة لمصدر] Criminal prosecutions followed, and the SPI was disbanded. The same year the government established Fundação Nacional do Índio (National Indian Foundation), known as FUNAI which is responsible for protecting the interests, cultures, and rights of the Brazilian indigenous populations. Some tribes have become significantly integrated into Brazilian society. The unacculturated tribes which have been contacted by FUNAI, are supposed to be protected and accommodated within Brazilian society in varying degrees. By 1987 it was recognized that unessential contact with the tribes was causing illness and social disintegration. The uncontacted tribes are now supposed to be protected from intrusion and interference in their lifestyle and territory.[34] However, the exploitation of rubber and other Amazonic natural resources has led to a new cycle of invasion, expulsion, massacres and death, which continues to this day.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The military government

Also in 1964, in a seismic political shift, the Brazilian military took control of the government and abolished all existing political parties, creating a two-party system. For the next two decades, Brazil was ruled by a series of generals. The country's mantra was "Brazil, the Country of the Future," which the military government used as justification for a giant push into the Amazon to exploit its resources, thereby beginning to transform Brazil into one of the leading economies of the world. Construction began on a transcontinental highway across the Amazon basin, aimed to encourage migration to the Amazon and to open up the region to more trade. With funding from World Bank, thousands of square miles of forest were cleared without regard for reservation status. After the highway projects came giant hydroelectric projects, then swaths of forest were cleared for cattle ranches. As a result, reservation lands suffered massive deforestation and flooding. The public works projects attracted very few migrants, but those few – and largely poor – settlers brought new diseases that further devastated the Amerindian population.

Contemporary situation

The 1988 Brazilian Constitution recognizes indigenous people's right to pursue their traditional ways of life and to the permanent and exclusive possession of their "traditional lands", which are demarcated as Indigenous Territories.[35] In practice, however, Brazil's indigenous people still face a number of external threats and challenges to their continued existence and cultural heritage.[36] The process of demarcation is slow—often involving protracted legal battles—and FUNAI do not have sufficient resources to enforce the legal protection on indigenous land.[37][36][38][39][40] Since the 1980s there has been a boom in the exploitation of the Amazon Rainforest for mining, logging and cattle ranching, posing a severe threat to the region's indigenous population. Settlers illegally encroaching on indigenous land continue to destroy the environment necessary for indigenous people's traditional ways of life, provoke violent confrontations and spread disease.[36] People such as the Akuntsu and Kanoê have been brought to the brink of extinction within the last three decades.[41][42] Deforestation for mining also affects the daily lives of indigenous tribes in Brazil.[43] For instance, the Munduruku Amerindians have higher levels of mercury poisoning due to gold production in the area.[44] On 13 November 2012, the national indigenous people association from Brazil APIB submitted to the United Nation a human rights document that complaints about new proposed laws in Brazil that would further undermine their rights if approved.[4]

Much of the language has been incorporated into the official Brazilian Portuguese language. For example, 'Carioca' the word used to describe people born in the city of Rio de Janeiro, is from the indigenous word for 'house of the white (people)'.[45]

Within hours of taking office in January 2019, Bolsonaro made two major changes to FUNAI, affecting its responsibility to identify and demarcate indigenous lands: He moved FUNAI from under the Ministry of Justice to under the newly created Ministry of Human Rights, Family and Women, and he delegated the identification of the traditional habitats of indigenous people and their designation as inviolable protected territories − a task attributed to FUNAI by the constitution – to the Agriculture Ministry.[46][47] He argued that those territories have tiny isolated populations and proposed to integrate them into the larger Brazilian society. Critics feared that such integration would lead the Brazilian natives to suffer cultural assimilation.[48][49] Several months later, Brazil's National Congress overturned these changes.

The European Union–Mercosur free trade agreement, which would form one of the world's largest free trade areas, has been denounced by environmental activists and indigenous rights campaigners.[50][51] The fear is that the deal could lead to more deforestation of the Amazon rainforest as it expands market access to Brazilian beef.[52]

A 2019 report by the Indigenous Missionary Council on Violence against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil documented an increase in the number of invasions of indigenous lands by loggers, miners and land grabbers, recording 160 cases in the first nine months of 2019, up from 96 cases in the entirety of 2017. The number of reported killings in 2018, 135, had also increased from 110 recorded in 2017.[53]

On 5 May 2020, post-HRW's investigation, Brazilian lawmakers released a report examining the violence against Indigenous people, Afro-Brazilian rural communities and others engaged in illegal logging, mining, and land grabbing.[54]

Indigenous rights movements

Urban rights movement

The urban rights movement is a recent development in the rights of indigenous peoples. Brazil has one of the highest income inequalities in the world,[55] and much of that population includes indigenous tribes migrating toward urban areas both by choice and by displacement. Beyond the urban rights movement, studies have shown that the suicide risk among the indigenous population is 8.1 times higher than the non-indigenous population.[56]

Many indigenous rights movements have been created through the meeting of many indigenous tribes in urban areas. For example, in Barcelos, an indigenous rights movement arose because of "local migratory circulation.[57]" This is how many alliances form to create a stronger network for mobilization. Indigenous populations also living in urban areas have struggles regarding work. They are pressured into doing cheap labor.[58] Programs like Oxfam have been used to help indigenous people gain partnerships to begin grassroots movements.[59] Some of their projects overlap with environmental activism as well.

Many Brazilian youths are mobilizing through the increased social contact, since some indigenous tribes stay isolated while others adapt to the change.[60] Access to education also affects these youths, and therefore, more groups are mobilizing to fight for indigenous rights.

Environmental and territorial rights movement

Dynamics favouring recognition

Many of the indigenous tribes' rights and rights claims parallel the environmental and territorial rights movement. Although indigenous people have gained 21% of the Brazilian Amazon as part of indigenous land, many issues still affect the sustainability of Indigenous territories today.[61][44] Climate change is one issue that indigenous tribes attribute as a reason to keep their territory.

Some indigenous peoples and conservation organizations in the Brazilian Amazon have formed alliances, such as the alliance of the A'ukre Kayapo village and the Instituto SocioAmbiental (ISA) environmental organization. They focus on environmental, education and developmental rights.[62] For example, Amazon Watch collaborates with various indigenous organizations in Brazil to fight for both territorial and environmental rights.[63] "Access to natural resources by indigenous and peasant communities in Brazil has been considerably less and much more insecure,"[64] so activists focus on more traditional conservation efforts, and expanding territorial rights for indigenous people.

Territorial rights for the indigenous populations of Brazil largely fall under socio-economic issues. There have been violent conflicts regarding rights to land between the government and the indigenous population,[43] and political rights have done little to stop them. There have been movements of the landless (MST) that help keep land away from the elite living in Brazil.[65]

Dynamics opposing recognition

Environmentalists and indigenous peoples have been viewed as opponents to economic growth and barriers to development[66] due to the fact that much of the land that indigenous tribes live on could be used for development projects, including dams, and more industrialization.

Groups self-identifying as indigenous may lack intersubjective recognition, thus claims to TIs, which can involve the demarcation of large areas of territory and threaten to dispossess established local communities, can be challenged by others, even neighbouring kinship groups, on the grounds that those making the claims are not 'real Indians', due to factors such as historical intermarriage (miscegenation), cultural assimilation, and stigma against self-identifying as indigenous. Claims to TIs can also be opposed by major landowning families from the rubber era, or by the peasants that work the land, who may instead prefer to support the concept of the extractive reserve.[67]

Education

The Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous History and Culture Law (Law No. 11.645/2008) is a Brazilian law mandating the teaching of Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous History and Culture which was passed and came into effect on 10 March 2008. It amends Law No. 9.394, of 20 December 1996, modified by Law No. 10.639, of 9 January 2003, which established the guidelines and bases of Brazilian national education, to include in the official curriculum of the education system the mandatory theme of Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous History and Culture.

الجماعات العرقية الرئيسية

For complete list see List of Indigenous peoples in Brazil

- Amanayé

- Atikum

- Awá-Guajá

- Baniwa

- Botocudo

- Bará

- Enawene Nawe

- Guaraní

- Kadiwéu

- Kaingang

- Kamayurá (Kamaiurá)

- Karajá

- Kayapo

- Kubeo

- Kaxinawá

- Kokama

- Korubo

- Kulina Madihá

- Mbya

- Makuxi

- Matsés

- Mayoruna

- Munduruku

- Mura people

- Nambikwara

- Ofayé

- Pai Tavytera

- Panará

- Pankararu

- Pataxó

- Pirahã

- Paiter

- Potiguara

- Sateré Mawé

- Suruí do Pará

- Tapirape

- Terena

- Ticuna

- Tremembé

- Tupi

- Waorani

- Wapixana

- Wauja

- Witoto

- Xakriabá

- Xavante

- Xukuru

- Yanomami

انظر أيضاً

- Amazon Watch

- Amerindians

- Archaeology of the Americas

- Agriculture in Brazil

- Bandeirantes

- Belo Monte Dam

- Bering Land Bridge

- Camarão indians' letters

- Darcy Ribeiro

- Encyclopedia of Indigenous Peoples in Brazil

- Ecotourism in the Amazon rainforest

- Chief Raoni

- COIAB

- Ceibo Alliance

- Brazilians

- Fundação Nacional do Índio

- Indigenous Peoples Day

- Índia pega no laço

- Indigenous peoples of South America

- Man of the Hole

- Museu do Índio

- Uncontacted peoples

- Percy Fawcett

- Sydney Possuelo

- Villas Boas brothers

المراجع

- ^ أ ب "Brasil tem quase 1,7 milhão de indígenas, aponta Censo 2022". Folha de S.Paulo (in البرتغالية البرازيلية). 2023-08-07. Retrieved 2023-08-07.

- ^ (in برتغالية) Study Panorama of religions. Fundação Getúlio Vargas, 2003.

- ^ Native Brazilians Informations

- ^ أ ب "English version of human rights complaint document submitted to the United Nations by the National Indigenous Peoples Organization from Brazil (APIB)". Earth Peoples. 13 November 2012. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ Patricia J. Ash; David J. Robinson (2011). The Emergence of Humans: An Exploration of the Evolutionary Timeline. John Wiley & Sons. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-119-96424-7.

- ^ Linda S. Cordell; Kent Lightfoot; Francis McManamon; George Milner (2008). Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. ABC-CLIO. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-313-02189-3.

- ^ "Summary of knowledge on the subclades of Haplogroup Q". Genebase Systems. 2009. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ أ ب Reich, D; Patterson, N; Campbell, D; Tandon, A; Mazieres, S; Ray, N; Parra, MV; Rojas, W; Duque, C (2012). "Reconstructing Native American population history". Nature. 488 (7411): 370–374. Bibcode:2012Natur.488..370R. doi:10.1038/nature11258. PMC 3615710. PMID 22801491.

- ^ Tamm, Erika; Kivisild, Toomas; Reidla, Maere; Metspalu, Mait; Smith, David Glenn; Mulligan, Connie J.; Bravi, Claudio M.; Rickards, Olga; Martinez-Labarga, Cristina; Khusnutdinova, Elsa K.; Fedorova, Sardana A.; Golubenko, Maria V.; Stepanov, Vadim A.; Gubina, Marina A.; Zhadanov, Sergey I.; Ossipova, Ludmila P.; Damba, Larisa; Voevoda, Mikhail I.; Dipierri, Jose E.; Villems, Richard; Malhi, Ripan S.; Carter, Dee (5 September 2007). "Beringian Standstill and Spread of Native American Founders". PLOS ONE. 2 (9): e829. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..829T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000829. PMC 1952074. PMID 17786201.

- ^ Llamas, Bastien; Fehren-Schmitz, Lars; Valverde, Guido; Soubrier, Julien; Mallick, Swapan; Rohland, Nadin; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Valdiosera, Cristina; Richards, Stephen M.; Rohrlach, Adam; Romero, Maria Inés Barreto; Espinoza, Isabel Flores; Cagigao, Elsa Tomasto; Jiménez, Lucía Watson; Makowski, Krzysztof; Reyna, Ilán Santiago Leboreiro; Lory, Josefina Mansilla; Torrez, Julio Alejandro Ballivián; Rivera, Mario A.; Burger, Richard L.; Ceruti, Maria Constanza; Reinhard, Johan; Wells, R. Spencer; Politis, Gustavo; Santoro, Calogero M.; Standen, Vivien G.; Smith, Colin; Reich, David; Ho, Simon Y. W.; Cooper, Alan; Haak, Wolfgang (1 April 2016). "Ancient mitochondrial DNA provides high-resolution time scale of the peopling of the Americas". Science Advances. 2 (4): e1501385. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E1385L. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1501385. PMC 4820370. PMID 27051878.

- ^ Dediu, Dan; Levinson, Stephen C. (20 September 2012). "Abstract Profiles of Structural Stability Point to Universal Tendencies, Family-Specific Factors, and Ancient Connections between Languages". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e45198. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...745198D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045198. PMC 3447929. PMID 23028843.

- ^ Raghavan; et al. (21 August 2015). "Genomic evidence for the Pleistocene and recent population history of Native Americans". Science. 349 (6250): aab3884. doi:10.1126/science.aab3884. PMC 4733658. PMID 26198033.

- ^ Skoglund, P; Mallick, S; Bortolini, MC; Chennagiri, N; Hünemeier, T; Petzl-Erler, ML; Salzano, FM; Patterson, N; Reich, D (21 July 2015). "Genetic evidence for two founding populations of the Americas". Nature. 525 (7567): 104–8. Bibcode:2015Natur.525..104S. doi:10.1038/nature14895. PMC 4982469. PMID 26196601.

- ^ Skoglund, P.; Reich, D. (2016). "A genomic view of the peopling of the Americas". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 41: 27–35. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2016.06.016. PMC 5161672. PMID 27507099.

- ^ Deposits in several places along the Amazon Archived 28 سبتمبر 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge University Press. 2000. p. 19.

- ^ أ ب ت Mann, Charles C. (2006) [2005]. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Vintage Books. pp. 326–333. ISBN 978-1-4000-3205-1.

- ^ Grann, David (2009). The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon. Doubleday. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-385-51353-1.

- ^ Roosevelt, Anna C. (1991). Moundbuilders of the Amazon: Geophysical Archaeology on Marajó Island, Brazil. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-125-95348-1.

- ^ Wren, Kathleen (2 December 2003). "Lost cities of the Amazon revealed". NBC News.

- ^ Boundary details are partly derived from Tribos Indígenas Brasileiras Archived 3 يوليو 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ M. Pereira Gomes, The Indians and Brazil, p.32

- ^ Leslie Bethell, MARY AMAZONAS LEITE DE BARROS . "História da América Latina: América Latina Colonial Vol. 2". EdUSP. São Paulo, p.317, 1997.

- ^ [1], Joseph – Francois Lafitau, 1700.

- ^ "Estimated indigenous populations of the Americas at the time of European contact, beginning in 1492". Retrieved 2023-04-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Brazilian Indians". survivalinternational.org/tribes/brazilian. Retrieved 2021-07-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ أ ب Lippy, Charles H. (1992). Christianity comes to the Americas, 1492–1776. Choquette, Robert, 1938–, Poole, Stafford. (1st ed.). New York, N.Y.: Paragon House. ISBN 1-55778-234-2. OCLC 23648978.

- ^ Caraman, Philip, 1911–1998. (1975). The lost paradise : an account of the Jesuits in Paraguay, 1607–1768. London: Sidgwick and Jackson. ISBN 0-283-98212-8. OCLC 2187394.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Eisenberg, José (2004). "A escravidão voluntária dos índios do Brasil e o pensamento político moderno" (PDF). Análise Social (in Portuguese). XXXIX (170): 7–35. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Knauß, Stefan (2010). "'Jesuit Engagement in Brazil between 1549 and 1609 – A legitimate support of Indians' emancipation or Eurocentricmovement of conversion?'". Astrolabio. Revista internacional de filosofíaAño: 227–238.

- ^ Roehner, Bertrand M. (1 April 1997). "Jesuits and the State: A Comparative Study of their Expulsions (1590–1990)". Religion. 27 (2): 165–182. doi:10.1006/reli.1996.0048.

- ^ Bucciferro, Justin R. (2013-07-03). "A Forced Hand: Natives, Africans, and the Population of Brazil, 1545-1850" (PDF). Revista de Historia Económica / Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History (in English). Cambridge University Press (CUP). 31 (2): 285–317. doi:10.1017/s0212610913000104. hdl:10016/27364. ISSN 0212-6109. S2CID 154533961. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Notícias socioambientais :: Socioambiental". socioambiental.org. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ أ ب "FUNAI – National Indian Foundation (Brazil)". Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Federal Constitution of Brazil. Chapter VII Article 231 Archived 1 يناير 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ أ ب ت "Brazil". 2008 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. U.S. Department of State.

- ^ "Indigenous Lands > Introduction > About Lands". Povos Indígenas no Brasil. Instituo Socioambiental (ISA). Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Borges, Beto; Combrisson, Gilles. "Indigenous Rights in Brazil: Stagnation to Political Impasse". South and Meso American Indian Rights Center. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Schwartzman, Stephan (1 March 1996). "Brazil The Legal Battle Over Indigenous Land Rights". NACLA Report on the Americas. 29 (5): 36–43. doi:10.1080/10714839.1996.11725759.

- ^ "Brazilian Indians 'win land case'". BBC News. 11 December 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Instituto Socioambiental (ISA). "Introduction > Akuntsu". Povos Indígenas no Brasil. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ Instituto Socioambiental (ISA). "Introduction > Kanoê". Povos Indígenas no Brasil. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ أ ب Paixao, Silvane; Hespanha, João P.; Ghawana, Tarun; Carneiro, Andrea F.T.; Zevenbergen, Jaap; Frederico, Lilian N. (1 December 2015). "Modeling indigenous tribes' land rights with ISO 19152 LADM: A case from Brazil". Land Use Policy. 49: 587–597. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.12.001.

- ^ أ ب Oliveira Santos, Elisabeth C. de; Maura de Jesus, Iracina; Camara, Volney e M.; Brabo, Edilson; Brito Loureiro, Edvaldo C.; Mascarenhas, Artur; Weirich, Judith; Ragio Luiz, Ronir; Cleary, David (1 October 2002). "Mercury exposure in Munduruku Indians from the community of Sai Cinza, state of Para, Brazil". Environmental Research. 90 (2): 98–103. Bibcode:2002ER.....90...98D. doi:10.1006/enrs.2002.4389. OSTI 20390954. PMID 12483799. S2CID 22429649.

- ^ "Dicionário Ilustrado Tupi-Guarani". 27 February 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ Karla Mendes (2019-06-05). "Brazil's Congress reverses Bolsonaro, restores Funai's land demarcation powers". news.mongabay.com. Retrieved 2019-08-03.

- ^ Marian Blasberg, Marco Evers, Jens Glüsing, Claus Hecking (2019-01-17). "Swath of Destruction: New Brazilian President Takes Aim at the Amazon". Spiegel Online. spiegel.de. Retrieved 2019-08-03.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Brazil's new president makes it harder to define indigenous lands". Global News. 2 January 2019.

- ^ "President Bolsonaro 'declares war' on Brazil's indigenous peoples – Survival responds". Survival International. 3 January 2019.

- ^ "EU urged to halt trade talks with S. America over Brazil abuses". France24. 18 June 2019.

- ^ "EU and Mercosur agree huge trade deal after 20-year talks". BBC News. 28 June 2019.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (2 July 2019). "We must not barter the Amazon rainforest for burgers and steaks". The Guardian.

- ^ Santana, Renato (24 September 2019). "A maior violência contra os povos indígenas é a destruição de seus territórios, aponta relatório do Cimi" [The greatest violence against indigenous peoples is the destruction of their territories, points out a Cimi report] (in البرتغالية البرازيلية).

- ^ "Brazil Analyzing Violence Against the Amazon's Residents". HumanRightsWatch. 26 May 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Poverty Analysis – Brazil: Inequality and Economic Development in Brazil". web.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ^ Orellana, Jesem D.; Balieiro, Antônio A.; Fonseca, Fernanda R.; Basta, Paulo C.; Souza, Maximiliano L. Ponte de (2016). "Spatial-temporal trends and risk of suicide in Central Brazil: an ecological study contrasting indigenous and non-indigenous populations". Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry. 38 (3): 222–230. doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2015-1720. PMC 7194261. PMID 26786195.

- ^ Sobreiro, Thaissa (2 November 2015). "Can urban migration contribute to rural resistance? Indigenous mobilization in the Middle Rio Negro, Amazonas, Brazil". The Journal of Peasant Studies. 42 (6): 1241–1261. doi:10.1080/03066150.2014.993624. S2CID 154162313.

- ^ Migliazza, Ernest G. (1978). The Integration of the Indigenous People of the Territory of Roraima, Brazil. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

- ^ Rocha, Jan (2000). Brazil. Latin America Bureau. ISBN 9781566563840.

- ^ Virtanen, Pirjo K. (2012). Indigenous Youth in Brazilian Amazonia: Changing Lived Worlds. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-26651-4.[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ Le Tourneau, François-Michel (1 June 2015). "The sustainability challenges of indigenous territories in Brazil's Amazonia" (PDF). Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 14: 213–220. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2015.07.017. S2CID 55113669.

- ^ Schwartzman, Stephan; Zimmerman, Barbara (2005). "Conservation Alliances with Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon". Conservation Biology. 19 (3): 721–727. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00695.x. S2CID 54681069.

- ^ Weik von Mossner, Alexa. Moving Environments: Affect, Emotion, Ecology, and Film.[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ Compensation for Environmental Services and Rural Communities.

- ^ Houtzager, Peter P. (2005). "The Movement of the Landless (MST), juridical field, and legal change in Brazil". Law and Globalization from Below. pp. 218–240. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511494093.009. ISBN 978-0-521-84540-3.

- ^ Zhouri, Andréa (1 September 2010). "'Adverse Forces' in the Brazilian Amazon: Developmentalism Versus Environmentalism and Indigenous Rights". The Journal of Environment & Development. 19 (3): 252–273. doi:10.1177/1070496510378097. S2CID 154971383.

- ^ Fraser, James Angus (2018). "Amazonian struggles for recognition". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 43 (4): 718–732. doi:10.1111/tran.12254.

وصلات خارجية

| Find more about Indigenous peoples in Brazil at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| Definitions from Wiktionary | |

| Media from Commons | |

| Quotations from Wikiquote | |

| Source texts from Wikisource | |

| Textbooks from Wikibooks | |

| Learning resources from Wikiversity | |

- Fundação Nacional do Índio, National Foundation of the Native American

- Encyclopedia of Indigenous people in Brazil. Instituto Socioambiental

- Etnolinguistica.Org: discussion list on South American languages

- Indigenous people Issues and Resources: Brazil

- Indigenous people in Brazil at Google Videos

- New photos of Uncontacted Brazilian tribe Archived 2 نوفمبر 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Google Video on Indigenous People of Brazil

- "Tribes" of Brazil

- Children of the Amazon, a documentary on indigenous people in Brazil

- Scientists find Evidence Discrediting Theory Amazon was Virtually Unlivable by The Washington Post

- CS1 البرتغالية البرازيلية-language sources (pt-br)

- Articles with برتغالية-language sources (pt)

- CS1 maint: url-status

- CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from April 2021

- الصفحات بخصائص غير محلولة

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- "Related ethnic groups" needing confirmation

- Articles using infobox ethnic group with image parameters

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 1997

- جميع المقالات التي فيها عبارات متقادمة

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2011

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2013

- Portal templates with default image

- الشعوب الأصلية في البرازيل

- Indigenous peoples of South America

- Ethnic groups in Brazil

- Race in Brazil