الخضابات الزرقاء

Blue pigments are natural or synthetic materials, usually made from minerals and insoluble with water, used to make the blue colors in painting and other arts. The raw material of the earliest blue pigment was lapis lazuli from mines in Afghanistan, that was refined into the pigment ultramarine. Since the late 18th and 19th century, blue pigments are largely synthetic, manufactured in laboratories and factories.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

صبغة اللازورد

Ultramarine was historically the most prestigious and expensive of blue pigments. It was produced from lapis lazuli, a mineral whose major source was the mines of Sar-e-Sang in what is now northeastern Afghanistan.[1] It was transformed into a pigment by the Afghans beginning in about the 5th century, and exported by caravans to India. It was the most expensive blue used by Renaissance artists. It was often reserved for special purposes, such as painting the robes of the Virgin Mary.[2] Johannes Vermeer used ultramarine only for the most important surfaces where he wanted to attract attention. Pietro Perugino, in his depiction of the Madonna and Child on the Certosa de Pavio Altarpiece, painted only the top level of the Virgin's robes in ultramarine, with azurite beneath.[3]

The Wilton Diptych (c. 1395–1399)

Unknown artistDetail from the Certosa di Pavia Altarpiece (c. 1496–1500)

Pietro PeruginoHet melkmeisje (1658)

يوهانس ڤرمير

Ultramarine became more widely used after its successful synthesis in the 19th century, which reduced its price substantially. In 1814, a French chemist named Tassaert observed the spontaneous formation of a blue compound, very similar to ultramarine, in a lime kiln at St. Gobain. In 1824, the Societé pour l'Encouragement d'Industrie offered a prize for the artificial production of the precious color. Processes were devised independently by Jean Baptiste Guimet (1826) and Christian Gmelin (1828); while Guimet kept his process a secret, Gmelin published his, and thus became the originator of the French synthetic ultramarine industry. At the beginning of the 19th century, the price of a kilogram of lapis lazuli was between six and ten thousand francs. The price of artificial ultramarine was less than eight hundred francs per kilogram.[4] Synthetic ultramarine was widely appreciated by the French impressionists, and Vincent van Gogh used both French ultramarine and cobalt blue for his painting The Starry Night (1889).[5]

الأزرق المصري

الأزرق المصري كان أول صبغة زرقاء اصطناعية. It was made from a mixture of silica, lime, copper, and an alkali. It was widely used in The Fourth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (c. 2613 to 2494 BC).[6] Egyptian blue is responsible for the blue colour seen very commonly in Egyptian faience.

Faience senet board belonging to أمنحوتپ الثالث (ح. 1390-1353 ق.م.)

Faience pyxis من شمال سوريا (ح. 750-700 BC)

أزرق الهان

أزرق الهان (also called Chinese blue) is a synthetic barium copper silicate pigment used in ancient and imperial China from the Western Zhou period (1045–771 BC) until the end of the Han dynasty (circa 220 AD). Han blue and the chemically related Han purple were used to decorate hu vessels during the Han dynasty, and were also used for mural paintings in tombs of the same period.[7]

Figures in a Han Dynasty tomb, painted with أزرق الهان (Before 220 AD)

A mural from a Han Dynasty tomb painted with both أزرق الهان وأرجواني الهان

أزرق المايا

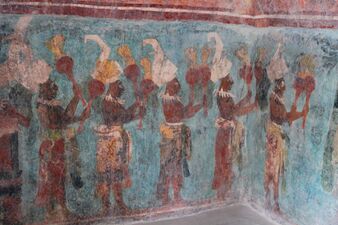

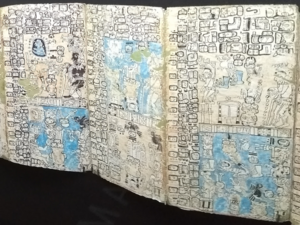

أزرق المايا is a synthetic turquoise-blue pigment made by infusing indigo dyes (particularly those derived from the anil shrub) into palygorskite, a clay that binds and stabilises the indigo such that it becomes resistant to weathering.[8] Developed in Mesoamerica in the first millennium AD, it saw wide use in the region, most prominently in the art of the Maya civilisation. It is known on media from pottery to murals to codices, and also played an important role in ritual sacrifices of both objects and people: silt at the bottom of the Sacred Cenote at Chichén Itzá is heavily stained with Maya blue, washed off the hundreds of sacrificial offerings cast into the cenote during the city's occupation.[9] Maya blue continued to be used into the Spanish colonial period; though falling out of widespread use in the Maya region during the 16th century, some areas apparently continued to produce it for export, as Cuban colonial paintings of the 18th and 19th century have been found to make use of Maya blue probably imported from Campeche.[10]

Fresco mural, Temple of the Murals at Bonampak (c. 790)

Pages 34–36 of the Madrid Codex (c. 1200–1500)

Ceiling mural at the Convento de la Asunción Tecamachalco, Puebla (1562)

Juan Gerson

أزوريت

صبغة الأزوريت is derived from the soft, deep-blue copper mineral of the same name, which forms from the weathering of copper ore deposits. It was mentioned in Pliny the Elder's Natural History under the Greek name kuanos (κυανός: "deep blue," root of English cyan) and the Latin name caeruleum. The modern English name of the mineral reflects this association, since both azurite and azure are derived via Arabic from the Persian lazhward (لاژورد), an area known for its deposits of another deep-blue stone, لازورد. Azurite was often used in the Renaissance and later as a less expensive substitute for ultramarine. Lower layers would be painted in azurite, with the most visible portions painted in ultramarine. The drawback of the pigment is that it degrades and darkens over time.[11]

Azurite crystals found from جبال لا سال، يوتا

أزرق پروسيا

أزرق پروسيا is a dark blue pigment containing iron and cyanide produced by the oxidation of ferrous ferrocyanide salts. It was invented in Berlin between 1704 and 1710. It had an immediate impact on the pigment market, because its intense deep blue color approached the quality of ultramarine at a much lower price. It was widely adapted by major European artists, notably Thomas Gainsborough and Canaletto, who used it to paint the Venetian sky.[12] It was also used by Japanese artists, including هوكوساي, for the deeper blues of waves.

Kanagawa-oki nami ura (الموجة الكبيرة أمام كاناگاوا) (1831)

هوكوساي

Cerulean blue

Cerulean blue was created in 1789 by the Swiss chemist Albrecht Höpfner.[13] Subsequently, there was a limited German production under the name of Cölinblau. The primary chemical constituent of the pigment is cobalt(II) stannate (Co 2SnO 4).[14]

Jour d'été (Summer's Day) (1879)

Berthe Morisot

أزرق الكوبالت

أزرق الكوبالت is a synthetic blue pigment was invented in 1803 as a rival to ultramarine. It was made by the process of sintering, that is by compacting and forming a solid mass of material by heat or pressure without melting it to the point of liquefaction. It combined cobalt(II) oxide with aluminum(III) oxide (alumina) at 1200 °C. It was also used as colorant, particularly in blue glass and as the blue pigment used for centuries in Chinese blue and white porcelain, beginning in the late eighth or early ninth century.[15]

Cobalt glass, or Smalt, is a variation of cobalt blue. It is made of ground blue potassium glass containing cobalt blue. It was widely used in painting in the 16th and the 17th centuries. Smalt was popular because of its low cost; it was widely used by Dutch and Flemish painters, including Hans Holbein the Younger.[16]

La Yole (Boating on the Seine) (c. 1879)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

أزرق الإتريوم والإنديوم والمنجنيز

أزرق اليين من هو صبغة غير عضوية ذات لون أزرق شديد الزرقة اكتشفها Mas Subramanian and his graduate student, Andrew Smith, at Oregon State University in 2009.[17][18] It has been used in water, oil and acrylic paints from paint vendors including Derivan,[19][20] Golden[21] and Gamblin.[22]

The name ”YInMn” comes from the chemical symbols for yttrium, indium and manganese. The intense blue color comes from the crystal structure of the chemical compound, and can be varied by adjusting the ratio of indium and manganese. After discovering this pigment, Subramanian’s research team has used similar principles of colour science to designed a range of novel green, purple, and orange pigments.[23][24][25]

قائمة الأصباغ الزرقاء غير العضوية

This is a list of blue inorganic pigments, both natural and synthetic.:[26]

Aluminium pigments

- Ultramarine (PB29): a synthetic or naturally occurring sulfur-containing silicate mineral - Na 8–10Al 6Si 6O 24S 2–4 (generalized formula)

- Persian blue: made by grinding up the mineral Lapis lazuli. The most important mineral component of lapis lazuli is lazurite (25% to 40%), a feldspathoid silicate mineral with the formula (Na,Ca) 8(AlSiO 4) 6(S,SO 4,Cl) 1–2.

Cobalt pigments

- Cobalt blue (PB28): cobalt(II) aluminate.

- Cerulean blue (PB35): cobalt(II) stannate.

- Cerium uranium blue

Copper pigments

- Egyptian blue: a synthetic pigment of calcium copper silicate (CaCuSi4O10). Thought to be the first synthetically produced pigment.

- Han blue: BaCuSi4O10.

- Azurite: cupric carbonate hydroxide (Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2).

- Basic copper carbonate: Cu2(OH)2CO3.

Iron pigments

- Prussian blue (PB27): a synthetic inert pigment made of iron and cyanide: C18Fe7N18.

Manganese pigments

- YInMn Blue: a synthetic pigment discovered in 2009 (YIn1−xMnxO3).[17]

- Manganese blue: barium manganate(VI) sulfate.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Notes and citations

- ^ Bomford and Roy, "A Closer Look at Colour" (2009), p. 28-37

- ^ Varichon, (2005) p. 164

- ^ Pastoureau, Michel, "Bleu - Histoire d'une couleur" (2000), p. 100

- ^ Maerz and Paul (1930). A Dictionary of Color New York: McGraw Hill p. 206

- ^ Yonghui Zhao, Roy S. Berns, Lawrence A. Taplin, James Coddington, An Investigation of Multispectral Imaging for the Mapping of Pigments in Paintings, in Proc. SPIE 6810, Computer Image Analysis in the Study of Art, 681007 (29 February 2008)

- ^ McCouat, Philip (2018). "Egyptian blue: The colour of technology". artinsociety.com. Journal of Art in Society. Archived from the original on 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- ^ FitzHugh, E. W. and Zycherman, L. A. 1992. A Purple Barium Copper Silicate Pigment from Early China. Studies in Conservation 28/1, 15–23.

- ^ Sánchez del Río, M.; Doménech, A.; Doménech-Carbó, M. T.; Vázquez de Agredos Pascual, M. L.; Suárez, M.; García-Romero, E. (2011). "18". In Galàn, E.; Singer, A. (eds.). Developments in Clay Science 3: Developments in Palygorskite-Sepiolite Research. Elsevier. pp. 453–481. ISBN 978-0-444-53607-5.

- ^ Arnold, D. E.; Branden, J. R.; Williams, P. R.; Feinman, G. M.; Brown, J. P. (2008). "The first direct evidence for the production of Maya Blue: rediscovery of a technology". Antiquity. 82 (315): 151–164. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00096514.

- ^ Tagle, A. A.; Paschinger, H.; Richard, H.; Infante, G. (1990). "Maya blue: its presence in Cuban colonial wall paintings". Studies in Conservation. 35 (3): 156–159. doi:10.1179/sic.1990.35.3.156.

- ^ Gettens, R.J. and Fitzhugh, E.W., Azurite and Blue Verditer, in Artists’ Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 2: A. Roy (Ed.) Oxford University Press 1993, p. 23–24

- ^ Bomford and Roy, "A Closer Look - Colour", the National Gallery, London (2009),p. 37

- ^ Höpfner, Albrecht (1789). "Einige kleine Chymische Versuche vom Herausgeber". Magazin für die Naturkunde Helvetiens. 4: 41–47.

- ^ "Cerulean blue - Overview". webexhibits.org. Pigments through the Ages. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ "Chinese pottery: The Yuan dynasty (1206–1368)". Archived 2017-12-29 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Accessed 7 June 2018.

- ^ Smalt Pigments through the Ages

- ^ أ ب Smith, Andrew E.; Mizoguchi, Hiroshi; Delaney, Kris; Spaldin, Nicola A.; Sleight, Arthur W.; Subramanian, M. A. (2009). "Mn3+ in Trigonal Bipyramidal Coordination: A New Blue Chromophore". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131: 17084–17086. doi:10.1021/ja9080666. PMID 19899792.

- ^ Cascone, Sarah (20 June 2016). "The Chemist Who Discovered the World's Newest Blue Explains Its Miraculous Properties". Artnet News. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020.

- ^ "Product Profile: Yin Min Blue". YouTube. Derivan. 12 July 2016. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- ^ Cascone, Sarah (19 June 2017). "The Wild Blue Yonder: How the Accidental Discovery of an Eye-Popping New Color Changed a Chemist's Life". Artnet. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ "Update on YInMn Blue from GOLDEN's Custom Lab". 2021-04-23. Retrieved 2021-08-18.

- ^ "Gamblin YInMn Blue".

- ^ Smith, Andrew E.; et al. (October 2016). "Spectral properties of the UV absorbing and near-IR reflecting blue pigment, YIn1−xMnxO3". Dyes and Pigments. 133: 214–221. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2016.05.029.

- ^ Li, Jun & Subramanian, M. A. (April 2019). "Inorganic pigments with transition metal chromophores at trigonal bipyramidal coordination: Y(In,Mn)O3 blues and beyond". Journal of Solid State Chemistry. 272: 9–20. Bibcode:2019JSSCh.272....9L. doi:10.1016/j.jssc.2019.01.019. S2CID 104373418.

- ^ Li, Jun; et al. (13 September 2016). "From Serendipity to Rational Design: Tuning the Blue Trigonal Bipyramidal Mn3+ Chromophore to Violet and Purple through Application of Chemical Pressure". Inorganic Chemistry. 55 (19): 9798–9804. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b01639. PMID 27622607.

- ^ Völz, Hans G.; et al. "Pigments, Inorganic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a20_243.pub2.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|authors=(help).

Bibliography

- Pastoureau, Michel (2000). Bleu : Histoire d'une couleur (in الفرنسية). Paris: Editions du Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-086991-1.

- Varichon, Anne (2005). Couleurs : pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples (in الفرنسية). Paris: Editions du Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-084697-4.

- Bomford, David; Roy, Ashok (2009). A Closer Look - Colour. London: National Gallery. ISBN 978-1857094428.