اللغة التوركية القديمة

| التوركية القديمة | |

|---|---|

| East Old Turkic, Old Turkic | |

| المنطقة | East Asia, Central Asia and parts of Eastern Europe |

| الحقبة | 8th–13th centuries |

Turkic

| |

| اللهجات | |

| Old Turkic script, Old Uyghur alphabet | |

| أكواد اللغات | |

| ISO 639-3 | otk – Old Turkish |

otk Old Turkish | |

| Glottolog | oldu1238 |

التوركية القديمة (Old Turkic ؛ أيضاً التوركية القديمة الشرقية، تركية أورخون، الأويغورية القديمة) هي أقدم صيغة مثبتة من التوركية، وُجـِدت في نقوش الگوقتورك والأويغور التي تعود إلى القرن السابع الميلادي حتى القرن الثالث عشر. وهي أقدم عضو مثبت في فرع أورخون من التوركية، الذي مازال موجوداً في لغة يوگور الغربية الحديثة. إلا أنها ليست سلف اللغة المسماة حالياً الأويغورية؛ السلف المعاصر للأويغور إلى الغرب يُدعى التوركية الوسيطة، ولاحقاً چقطاي أو توركي.

Old Turkic is attested in a number of scripts, including the Orkhon-Yenisei runiform script, the Old Uyghur alphabet (a form of the Sogdian alphabet), the Brāhmī script, the Manichean alphabet, and the Perso-Arabic script.

Old Turkic often refers not to a single language, but collectively to the closely related and mutually intelligible stages of various Common Turkic branches that were spoken during the late 1st millennium AD.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

بزوغ التوركية القديمة

اكتشاف وتحليل النقوش التوركية القديمة

In 1709, a Swedish officer named Strahlenberg discovered an inscription in Siberia that would be called Uybat III. This inscription is the first written document discovered in Turkish history. After Strahlenberg published his discoveries in Stockholm , the western world began to explore the region. First, a Finnish team, then a Russian team, was sent to explore the region. Nikolay Yadrintsev from the Russian team unearthed the Kul Tigin and Bilge Kagan inscriptions. YN Klements, also from the Russian team, discovered the Tonyukuk inscription. Following these discoveries, hundreds of stones of all sizes were unearthed.

On their return, the Finnish board published copies of the Kul Tigin and Bilge Kagan inscriptions. The translation of the Chinese side of the Kul Tigin inscription was also given in these publications. When it was understood from the translation that the inscription was erected in memory of a Turkic tigin , the famous Turkologists Vasili Radloff and Vilhelm Thomsen simultaneously began work on deciphering the inscriptions. Thomsen officially announced the analysis of the Orkhon Inscriptions on March 15, 1893. Following this step by Thomsen, Radloff published the first part of his work Erste Lieferung . Radloff made many mistakes because he acted hastily in his work. Thomsen, on the other hand, successfully analyzed the inscriptions without making any room for error in his work published under the title Inscriptions de l'Orkhon et de déchiffrées .

Radloff shared the continuation of his work in 1899. In this article, he also gave a copy and translation of the Tonyukuk inscription found at the Bain-Tsokto site. Thus, the analysis of the three large bengü stones and the Old Turkish script was completed.

اكتشاف المخطوطات الأويغورية

In 1890 , a British officer in East Turkestan bought a piece of bark with Sanskrit writings on it from the villagers and took it to the Oriental Institute in his country. When it was understood that this discovery pushed the history of Sanskrit back 600 years, the region attracted enormous interest. European and Japanese researchers who flocked to the region ( two separate German committees headed by Albert Grünwedel and AA von le Coq, a French committee headed by Paul Pelliot , a Japanese committee headed by Russian researcher Sergey Malov and Count Otani ) returned to their countries with chests full of manuscripts. These chests also contained a large number of Uyghur manuscripts. Hungarian researcher Aurel Stein, who had previously visited the region and taken chests full of manuscripts to England , returned to the region and went to the Bezeklik Caves . [13] The priest, the protector of the monasteries, first gave Stein a manuscript, but then regretted it and hid the library buried in the cave well. After a long struggle, Stein convinced the priest and entered the library, where he found thousands of manuscripts in almost every language. Stein took tons of manuscripts, including Irk Bitig and Sekiz Yükmek, back to his country. [12] Thus, Old Uyghur was also brought to light.

التهجي

مقالات مفصلة: الكتابة التوركية القديمة

مقالات مفصلة: الكتابة التوركية القديمة- الأبجدية الأويغورية

The first period of Old Turkish, Gokturkish, was not written with any other system than Old Turkic script . The Uyghurs who came after the Gokturks stopped using the old script and instead adopted a series of alphabets. The Uyghurs tried many abjad and syllabic scripts such as Sogdian , Manichaean , Brahmi , Estrangelo and Tibetan to write their language . After using these scripts for a short period, they started using the Uyghur script, which they developed from the Sogdian script.

The Old Turkic script is a system that is a mixture of syllabic and alphabetic scripts seen in many inscriptions. There are various ideas about its origin.According to the Turkologist Vilhelm Thomsen, who deciphered the Orkhon Inscriptions, the system was derived from the Aramaic script . [15] On the other hand, it is certain that a series of signs (/ok/ and /uk/, /äl/, /ot/) come from pictograms. [16]

There are 38 stamps in the regular form of the Orkhon alphabet used in the Bilge and Kultegin inscriptions. Four of these were used to write vowels, 26 consonants and the rest were used to write combined sounds. How vowels should be read was made clear by writing some letters differently according to thin and thick vowels. However, some consonants were excluded from this situation.

Although it is not known when the Orkhon script was first used, it was used until the middle of the 8th century AD. The most well-known places where the alphabet was used are the Orkhon inscriptions, the Yenisey Inscriptions and Irk Bitig .

The Uyghur alphabet first appeared in the 9th century AD and is an alphabet derived from the Sogdian alphabet. It consists of a total of 18 separate letters. As in the Orkhon alphabet, four of the 18 letters are vowels, but it does not contain signs that make it clear whether the vowels are read as thick or thin.

Before the Turks adopted the Uyghur alphabet, they left many documents with the Sogdian and Manichaean scripts from Sogdia , the Brahmi script from India , and the Tibetan script from Tibet , and then developed their own script. The script they developed, unlike the Orkhon script, continued to be used after the majority of the Turks converted to Islam. After the Uyghurs, it was used by the Karakhanids , the Mongol Empire , the Timurid Empire , and other states. [19]

The alphabet, as mentioned above, has 18 letters. Four of these 18 letters are used in writing the vowels. However, unlike the Orkhon script, there is no distinction between thin and thick consonants that indicates how the vowels are to be read. The fact that the letters are very similar to each other and that some separate consonants are shown with the same letter also makes reading difficult.

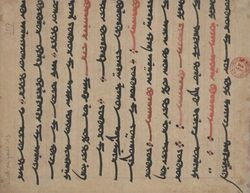

The most well-known works written in the Uyghur script are translations of Buddhist sutras and stories and their supplements, Manichaean texts, title deeds, receipts, decrees [20] and the Herat manuscript of the Kutadġu Bilig in the Uyghur script .

المصادر

مصادر التوركية القديمة تنقسم إلى مجمعين:

- the 7th to 10th century Orkhon inscriptions in Mongolia and the Yenisey basin (Orkhon Turkic, or Old Turkic proper).

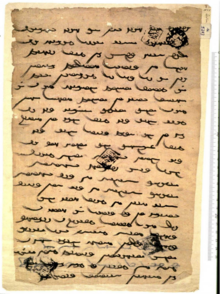

- 9th to 13th century Uyghur manuscripts from Xinjiang (Old Uyghur), in various scripts including Brahmi, the Manichaean, Syriac and Uyghur alphabets, treating religious (Buddhist, Manichaean and Nestorian), legal, literary, folkloric and astrologic material as well as personal correspondence.

نظم الكتابة

The Old Turkic script (also known variously as Göktürk script, Orkhon script, Orkhon-Yenisey script) is the alphabet used by the Göktürks and other early Turkic khanates during the 8th to 10th centuries to record the Old Turkic language.[1]

The script is named after the Orkhon Valley in Mongolia where early 8th-century inscriptions were discovered in an 1889 expedition by Nikolai Yadrintsev.[2]

This writing system was later used within the Uyghur Khaganate. Additionally, a Yenisei variant is known from 9th-century Yenisei Kirghiz inscriptions, and it has likely cousins in the Talas Valley of Turkestan and the Old Hungarian alphabet of the 10th century. Words were usually written from right to left. Variants of the script were found from Mongolia and Xinjiang in the east to the Balkans in the west. The preserved inscriptions were dated to between the 8th and 10th centuries.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الأصوات

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unr. | Rnd. | Unr. | Rnd. | |

| Close | i | y | ɯ | u |

| Mid | e | ø | o | |

| Open | ɑ | |||

Rounded vowels may only occur in the initial syllable. Length is distinctive for all vowels; while most of its daughter languages have lost the distinction, many of these preserve it in the case of /e/ with a height distinction, where the long phoneme developed into a more closed vowel than the short counterpart.

| Labial | Dental | Post- alveolar |

Velar | Uvular | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | tʃ | k | g | q | ɢ | |

| Fricative | s | z | ʃ | |||||||

| Tap/Flap | ɾ | |||||||||

| Approximant | ɫ | l | j | |||||||

Old Turkic is highly restrictive in which consonants words can begin with: /p/, /d/, /g/, /ɢ/, /l/, /ɾ/, /n/, /ɲ/, /ŋ/, /m/, /ʃ/, and /z/ are not allowed in a word-initial position. The only exceptions are 𐰤𐰀 (ne, “what, which”) and its derivatives, and some early assimilations of word-initial /b/ to /m/ preceding a nasal in a word such as 𐰢𐰤 (men, “I”).

اللواحق الإسمية

This is a partial list of nominal suffixes attested to in Old Turkic and known usages.

Denominal

The following have been classified by Gerard Clauson as denominal noun suffixes.

| Suffix | Usages | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| -ča | anča | at least one |

| -ke | sigirke yipke |

sinew string/thread |

| -la/-le | ayla tünle körkle |

thus, like that) yesterday, night, north) beautiful |

| -suq/-sük | bağïrsuq | liver, entrails |

| -ra/-re | içre | inside, within |

| -ya/-ye | bérye yırya |

here north |

| -čïl/-čil | igčil | sickly |

| -ğïl/-gil | üçgil qïrğïl |

triangular grey haired |

| -nti | ékkinti | second |

| -dam/-dem | tegridem | god-like |

| tïrtï:/-türti | ičtirti |

inside, within |

| -qı:/-ki | ašnuki üzeki ebdeki |

former on or above in the house |

| -an/-en/-un | oğlan eren |

children men, gentlemen |

| -ğu:/-gü | enčgü tuzğu buğrağu |

tranquil, at peace food given to a traveller as a gift woodwork |

| -a:ğu:/-e:gü: | üčegü ičegü |

three together inside human body |

| -dan/-dun | otun izden |

firewood track, trace |

| -ar/-er | birer azar |

one each a few |

| -layu:/-leyü | börileyü | like a wolf |

| -daš/-deš | qarïndaš yerdeš |

kinsman compatriot |

| -mïš/-miš | altmïš yetmiš |

sixty seventy |

| -gey | küçgey | violent |

| -çaq/-çek and -çuq/-çük | ïğïrčaq | spindle-whorl |

| -q/-k (after vowels and -r) -aq/-ek (the normal forms)/-ïq/-ik/-uq/-ük(rare forms) | ortuq | middle partner |

| -daq/-dek and(?) -duq/-dük | bağırdaq beligdek burunduq |

wrap terrifying nose ring |

| -ğuq/-gük | çamğuq | obectionable |

| -maq/-mek | kögüzmek | breastplate |

| -muq/-a:muq | solamuk | left-handed (pejorative?) |

| -naq | baqanaq | "frog in a horse's hoof" (from baqa frog) |

| -duruq/-dürük | boyunduruq | yoke |

Deverbal

The following have been classified by Gerard Clauson as deverbal suffixes.

| Suffix | Usages | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| -a/-e/-ı:/-i/-u/-ü | oprı adrı keçe egri köni ötrü |

hollow,valley branched,forked evening, night crooked straight, upright, lawful then, so |

| -ğa/-ge | kısğa öge bilge kölige tilge |

short wise wise shadow slice |

| -ğma/-gme | tanığma | riddle |

| -çı/-çi | otaçı: okıçı |

healer priest |

| -ğuçı/-güçi | ayğuçı bitigüçi |

councilor scribe |

| -dı/-di | üdründi ögdi alkadı sökti |

chosen,parted,separated,scattered customs praised bran |

| -tı/-ti | arıtı uzatı tüketi |

completely, clean lengthily completely |

| -du | eğdu umdul süktü |

curved knife desire, covetousness campaigning |

| -ğu:/-gü | bilegü kedgü oğlağü |

whetstone clothing gently nurtured |

| -ingü | bilingü etingü yeringü salingü |

be in the know be prepared disgusted be moving violently |

| -ğa:ç/-geç | kışgaç | pincers |

| -ğuç/-güç | bıçgüç | scissors |

| -maç/-meç | tutmaç | "saved" noodle dish |

| -ğut/-güt | alpağut bayağut |

warrior merchant |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

أمثلة

أعمال أدبية

- Uyuk-Tarlak inscription (date unknown) by an unknown writer (in Yenisei Kyrgyz)

- Elegest inscription (date unknown) by an unknown writer (in Yenisei Kyrgyz)

- Orkhon Inscriptions (732 and 735) by Yollıg Khagan (in Orkhon Turkic)

- Bain Tsokto inscriptions (716) by an unknown writer (in Orkhon Turkic)

- Ongin inscription (between 716 and 735) by an unknown writer (in Orkhon Turkic)

- Kul-chur inscription (between 723 and 725) a writer called "Ebizter" (in Orkhon Turkic)

- Altyn Tamgan Tarhan inscription (724) by an unknown writer (in Orkhon Turkic)

- Tariat inscriptions (between 753 and 760) by an unknown writer (in Old Uyghur)

- Choiti-Tamir inscriptions (between 753 and 756) by an unknown writer (in Old Uyghur)

- Sükhbaatar inscriptions (8th century) by an unknown writer (in Old Uyghur)

- Bombogor inscription (8th century) by an unknown writer (in Old Uyghur)

- Book of Divination (9th century) by an unknown writer (in Old Uyghur)

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- Ö.D. Baatar, Old Turkic Script, Ulan-Baator (2008), ISBN 0-415-08200-5

- M. Erdal, A Grammar of Old Turkic, Handbook of Oriental Studies, Section 8 Uralic & Central Asia, Brill, Leiden (2004), ISBN 90-04-10294-9.

- M. Erdal, Old Turkic word formation: A functional approach to the lexicon, Turcologica, Harassowitz (1991), ISBN 3-447-03084-4.

- Talat Tekin, A Grammar of Orkhon Turkic, Uralic and Altaic Series Vol. 69, Indiana University Publications, Mouton and Co. (1968). (review: Gerard Clauson, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 1969); Routledge Curzon (1997), ISBN 0-7007-0869-3.

- L. Johanson, A History of Turkic, in: The Turkic Languages, eds. L. Johanson & E.A. Csato, Routledge, London (1998), ISBN 0-415-08200-5

- M. Erdal, Old Turkic, in: The Turkic Languages, eds. L. Johanson & E.A. Csato, Routledge, London (1998), ISBN 978-99929-944-0-5

- ^ Scharlipp, Wolfgang (2000). An Introduction to the Old Turkish Runic Inscriptions. Verlag auf dem Ruffel, Engelschoff. ISBN 978-3-933847-00-3.

- ^ Sinor, Denis (2002). "Old Turkic". History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Vol. 4. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 331–333.

للاستزادة

- Noten zu den alttürkischen Inschriften der Mongolei und Sibiriens (1898)

- Marcel Erdal (1 January 2004). A Grammar Of Old Turkic. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10294-9.

وصلات خارجية

- Old Turkic inscriptions (with translations into English), reading lessons and tutorials

- Turkic Inscriptions of Orkhon Valley (with translations into Turkish)

- VATEC, pre-Islamic Old Turkic electronic corpus at uni-frankfurt.de.

- A Grammar of Old Turkic by Marcel Erdal

- Old Turkic (8th century) funerary inscription (W. Schulze)

- Kuli Chor inscription complete text

- Tonyukuk inscription complete text

- Kul Tigin inscription complete text

- Bilge Qaghan inscription complete text

- Eletmiš Yabgu (Ongin) inscription complete text

- Bayanchur Khan inscription complete text

- Ongin inscriptions by Gerard Clauson

- Missing redirects

- Languages which need ISO 639-3 comment

- Language articles with unreferenced extinction date

- Language articles with unsupported infobox fields

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing Old Turkic-language text

- Languages attested from the 7th century

- لغات إلصاقية

- لغات توركية

- لغات منقرضة في آسيا

- گوقتورك