اقتصاد الاتحاد السوڤيتي

The DniproHES hydro-electric power plant، أحد رموز القوة الاقتصادية السوڤيتية، وقد اكتمل في 1932 | |

| العملة | Soviet ruble (SUR)[1] |

|---|---|

| 1 January–31 December (calendar year)[1] | |

منظمات التجارة | Comecon, ESCAP and others[1] |

| احصائيات | |

| ن.م.إ | $820 billion in 1977 (nominal; 2nd) $1.212 trillion in 1980 (nominal; 2nd) $1.57 trillion in 1982 (nominal; 2nd) $2.2 trillion in 1985 (nominal; 2nd) $2.6595 trillion in 1989 (GNP; 2nd)[2] |

| ترتيب ن.م.إ | 3rd (nominal) 2nd (GNP) (1989 est.)[2][3] |

ن.م.إ للفرد | $5,800 in 1982 (nominal; 32nd) $9,211 in 1991 (GNP; 28th)[4] |

ن.م.إ للفرد | Agriculture: (1–2%) Industry: (–2.4%) (1991 est.)[1] |

| 14% (43rd) (1991)[5] | |

| 0.290 (1980 est.) 0.275 (1989 est.)[6] | |

القوة العاملة | 152.3 million (3rd) (1989 est.)[7] |

القوة العاملة حسب المهنة | 80% in industry and other non-agricultural sectors; 20% in agriculture (1989 est.)[1] |

| البطالة | 1–2%[1] |

الصناعات الرئيسية | Petroleum, steel, motor vehicles, aerospace, telecommunications, chemicals, heavy industries, electronics, food processing, lumber, mining and the defense (1989 est.)[1] |

| الخارجي | |

| الصادرات | $110.7 billion (9th) (1989 est.)[8] |

السلع التصديرية | Petroleum and petroleum products, natural gas, metals, wood, agricultural products and a wide variety of manufactured goods (1989 est.)[1] |

شركاء التصدير الرئيسيين | Eastern Bloc 49%, European Community 14%, Cuba 5%, الولايات المتحدة, Afghanistan (1988 est.)[1] |

| الواردات | $114.7 billion (10th) (1989 est.)[9] |

السلعة المستوردة | Grain and other agricultural products, machinery and equipment, steel products (including large-diameter pipe), consumer manufactures[1] |

شركاء الاستيراد الرئيسيين | Eastern Bloc 54%, European Community 11%, Cuba, الصين, United States (1988 est.)[1] |

إجمالي الديون الخارجية | $55 billion (11th) (1989 est.)[10] $27.3 billion (1988 est.)[11] |

| المالية العامة | |

| العوائد | $422 billion (5th) (1990 est.)[12] |

| النفقات | $510 billion (1989 est.)[1] $53 million (2nd; capital expenditures) (1991 est.)[13] |

| المعونات الاقتصادية | $147.6 billion (1954–1988)[1] |

كل القيم، ما لم يُذكر غير ذلك، هي بالدولار الأمريكي. | |

اقتصاد اتحاد الجمهوريات الاشتراكية السوڤيتية (روسية: экономика Советского Союза) كان مبنياً على نظام لـملكية الدولة لوسائل الانتاج والزراعة الجماعية والتصنيع والتخطيط الاداري المركزي. وقد اتسم الاقتصاد بسيطرة الدولة على الاستثمار والملكية العامة للأصول الصناعية، والاستقرار الاقتصادي، انعدام البطالة تقريباً وضمان الوظائف.[14]

Beginning in 1928, the course of the Soviet Union's economy was guided by a series of five-year plans. By the 1950s, during the preceding few decades the Soviet Union had rapidly evolved from a mainly agrarian society into a major industrial power.[15] Its transformative capacity—what the White House National Security Council of the الولايات المتحدة described as a "proven ability to carry backward countries speedily through the crisis of modernization and industrialization"—meant communism consistently appealed to the intellectuals of developing countries in Asia.[16] Impressive growth rates during the first three five-year plans (1928–1940) are particularly notable given that this period is nearly congruent with the Great Depression.[17] During this period, the Soviet Union encountered a rapid industrial growth while other regions were suffering from crisis.[18] Nevertheless, the impoverished base upon which the five-year plans sought to build meant that at the commencement of Operation Barbarossa the country was still poor.[19][20]

A major strength of the Soviet economy was its enormous supply of oil and gas, which became much more valuable as exports after the world price of oil skyrocketed in the 1970s. As Daniel Yergin notes, the Soviet economy in its final decades was "heavily dependent on vast natural resources–oil and gas in particular". However, Yergin goes on by saying that world oil prices collapsed in 1986, putting heavy pressure on the economy.[21] After Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985, he began a process of economic liberalization by dismantling the command economy and moving towards a mixed economy. At its dissolution at the end of 1991, the Soviet Union begat a Russian Federation with a growing pile of $66 billion in external debt and with barely a few billion dollars in net gold and foreign exchange reserves.[22]

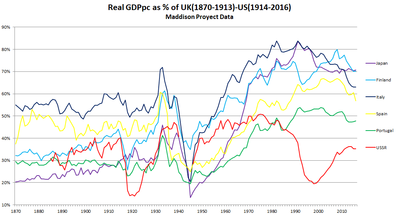

The complex demands of the modern economy somewhat constrained the central planners. Corruption and data fiddling became common practice among the bureaucracy by reporting fulfilled targets and quotas, thus entrenching the crisis. From the Stalin-era to the early Brezhnev-era, the Soviet economy grew much slower than Japan and slightly faster than the United States. GDP levels in 1950 (in billion 1990 dollars) were 510 (100%) in the Soviet Union, 161 (100%) in Japan and 1,456 (100%) in the United States. By 1965, the corresponding values were 1,011 (198%), 587 (365%) and 2,607 (179%).[23] The Soviet Union maintained itself as the second largest economy in both nominal and purchasing power parity values for much of the Cold War until 1988, when Japan's economy exceeded $3 trillion in nominal value.[24]

The Soviet Union's relatively small consumer sector accounted for just under 60% of the country's GDP in 1990 while the industrial and agricultural sectors contributed 22% and 20% respectively in 1991. Agriculture was the predominant occupation in the Soviet Union before the massive industrialization under Joseph Stalin. The service sector was of low importance in the Soviet Union, with the majority of the labor force employed in the industrial sector. The labor force totaled 152.3 million people. Major industrial products included petroleum, steel, motor vehicles, aerospace, telecommunications, chemicals, electronics, food processing, lumber, mining and defense industry. Though its GDP crossed $1 trillion in the 1970s and $2 trillion in the 1980s, the effects of central planning were progressively distorted due to the rapid growth of the second economy in the Soviet Union.[25]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التخطيط

Based on a system of state ownership, the Soviet economy was managed through Gosplan (the State Planning Commission), Gosbank (the State Bank) and the Gossnab (State Commission for Materials and Equipment Supply). Beginning in 1928, the economy was directed by a series of five-year plans, with a brief attempt at seven-year planning. For every enterprise, planning ministries (also known as the "fund holders" or fondoderzhateli) defined the mix of economic inputs (e.g. labor and raw materials), a schedule for completion, all wholesale prices and almost all retail prices. The planning process was based around material balances—balancing economic inputs with planned output targets for the planning period. From 1930 until the late 1950s, the range of mathematics used to assist economic decision-making was, for ideological reasons, extremely restricted.[26]

Industry was long concentrated after 1928 on the production of capital goods through metallurgy, machine manufacture, and chemical industry. In Soviet terminology, goods were known as capital. This emphasis was based on the perceived necessity for a very fast industrialization and modernization of the Soviet Union. After the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953, consumer goods (group B goods) received somewhat more emphasis due to efforts of Malenkov. However, when Nikita Khrushchev consolidated his power by sacking Georgy Malenkov, one of the accusations against Malenkov was that he permitted "theoretically incorrect and politically harmful opposition to the rate of development of heavy industry in favor of the rate of development of light and food industry".[27] Since 1955, the priorities were again given to capital goods, which was expressed in the decisions of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in 1956.[28]

Most information in the Soviet economy flowed from the top down. There were several mechanisms in place for producers and consumers to provide input and information that would help in the drafting of economic plans (as detailed below), but the political climate was such that few people ever provided negative input or criticism of the plan and thus Soviet planners had very little reliable feedback that they could use to determine the success of their plans. This meant that economic planning was often done based on faulty or outdated information, particularly in sectors with large numbers of consumers. As a result, some goods tended to be underproduced and led to shortages while other goods were overproduced and accumulated in storage. Low-level managers often did not report such problems to their superiors, relying instead on each other for support. Some factories developed a system of barter and either exchanged or shared raw materials and parts without the knowledge of the authorities and outside the parameters of the economic plan.

Heavy industry was always the focus of the Soviet economy even in its later years. The fact that it received special attention from the planners, combined with the fact that industrial production was relatively easy to plan even without minute feedback, led to significant growth in that sector. The Soviet Union became one of the leading industrial nations of the world. Industrial production was disproportionately high in the Soviet Union compared to Western economies. However, the production of consumer goods was disproportionately low. Economic planners made little effort to determine the wishes of household consumers, resulting in severe shortages of many consumer goods. Whenever these consumer goods would become available on the market, consumers routinely had to stand in long lines (queues) to buy them.[بحاجة لمصدر] A black market developed for goods such as cigarettes that were particularly sought after, but it constantly underproduced.

Drafting the five-year plans

Under Joseph Stalin's tutelage, a complex system of planning arrangements had developed since the introduction of the first five-year plan in 1928. Until the late 1980s and early 1990s, when economic reforms backed by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev introduced significant changes in the traditional system (see perestroika). the allocation of resources was directed by a planning apparatus rather than through the interplay of market forces.

Time frame

From the Stalin era through the late 1980s, the five-year plan integrated short-range planning into a longer time frame. It delineated the chief thrust of the country's economic development and specified the way the economy could meet the desired goals of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Although the five-year plan was enacted into law, it contained a series of guidelines rather than a set of direct orders.

Periods covered by the five-year plans coincided with those covered by the gatherings of the CPSU Party Congress. At each CPSU Congress, the party leadership presented the targets for the next five-year plan, therefore each plan had the approval of the most authoritative body of the country's leading political institution.

Guidelines for the plan

The Central Committee of the CPSU and more specifically its Politburo set basic guidelines for planning. The Politburo determined the general direction of the economy via control figures (preliminary plan targets), major investment projects (capacity creation) and general economic policies. These guidelines were submitted as a report of the Central Committee to the Congress of the CPSU to be approved there.

After the approval at the congress, the list of priorities for the five-year plan was processed by the Council of Ministers, which constituted the government of the Soviet Union. The Council of Ministers was composed of industrial ministers, chairmen of various state committees and chairmen of agencies with ministerial status. This committee stood at the apex of the vast economic administration, including the state planning apparatus, the industrial ministries, the trusts (the intermediate level between the ministries and the enterprises) and finally the state enterprises. The Council of Ministers elaborated on Politburo plan targets and sent them to Gosplan, which gathered data on plan fulfillment.

Gosplan

Combining the broad goals laid out by the Council of Ministers with data supplied by lower administrative levels regarding the current state of the economy, Gosplan worked out through trial and error a set of preliminary plan targets. Among more than twenty state committees, Gosplan headed the government's planning apparatus and was by far the most important agency in the economic administration. The task of planners was to balance resources and requirements to ensure that the necessary inputs were provided for the planned output. The planning apparatus alone was a vast organizational arrangement consisting of councils, commissions, governmental officials, specialists and so on charged with executing and monitoring economic policy.

The state planning agency was subdivided into its own industrial departments, such as coal, iron and machine building. It also had summary departments such as finance, dealing with issues that crossed functional boundaries. With the exception of a brief experiment with regional planning during the Khrushchev era in the 1950s, Soviet planning was done on a sectoral basis rather than on a regional basis. The departments of the state planning agency aided the agency's development of a full set of plan targets along with input requirements, a process involving bargaining between the ministries and their superiors.

وزارات التخطيط

Economic ministries performed key roles in the Soviet organizational structure. When the planning goals had been established by Gosplan, economic ministries drafted plans within their jurisdictions and disseminated planning data to the subordinate enterprises. The planning data were sent downward through the planning hierarchy for progressively more detailed elaboration. The ministry received its control targets, which were then disaggregated by branches within the ministry, then by lower units, eventually until each enterprise received its own control figures (production targets).

المؤسسات

Enterprises were called upon to develop in the final period of state planning in the late 1980s and early 1990s (even though such participation was mostly limited to a rubber-stamping of prepared statements during huge pre-staged meetings). The enterprises' draft plans were then sent back up through the planning ministries for review. This process entailed intensive bargaining, with all parties seeking the target levels and input figures that best suited their interests.

تعديل الخطة

After this bargaining process, Gosplan received the revised estimates and re-aggregated them as it saw fit. The redrafted plan was then sent to the Council of Ministers and the party's Politburo and Central Committee Secretariat for approval. The Council of Ministers submitted the plan to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union and the Central Committee submitted the plan to the party congress, both for rubber stamp approval. By this time, the process had been completed and the plan became law.

الموافقة على الخطة

The review, revision and approval of the five-year plan were followed by another downward flow of information, this time with the amended and final plans containing the specific targets for each sector of the economy. Implementation began at this point and was largely the responsibility of enterprise managers.

ميزانية الدولة

The national state budget was prepared by the Ministry of Finance of the Soviet Union by negotiating with its all-Union local organizations. If the state budget was accepted by the Soviet Union, it was then adopted.[29]

الزراعة

أشكال الملكية

الملكية الفردية

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الملكية الجماعية

التاريخ

التطور المبكر

Both the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and later the Soviet Union were countries in the process of industrialization. For both, this development occurred slowly and from a low initial starting-point. Because of World War I (1914–1918), the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the ensuing Russian Civil War (1917–1922), industrial production had only managed to barely recover its 1913 level by 1926.[30] By this time, about 18% of the population lived in non-rural areas, although only about 7.5% were employed in the non-agricultural sector. The remainder remained stuck in low-productivity agriculture.[31]

David A. Dyker sees the Soviet Union of circa 1930 as in some ways a typical developing country, characterized by low capital-investment and with most of its population resident in the countryside. Part of the reason[بحاجة لمصدر] for low investment-rates lay in the inability to acquire capital from abroad. This in turn, resulted from the repudiation of the debts of the Russian Empire by the Bolsheviks in 1918[32] as well as from the worldwide financial troubles. Consequently, any kind of economic growth had to be financed by domestic savings.[31]

The economic problems in agriculture were further exacerbated by natural conditions, such as long cold winters across the country, droughts in the south and acidic soils in the north. However, according to Dyker, the Soviet economy did have "extremely good" potential in the area of raw materials and mineral extraction, for example in the oil fields in Transcaucasia, and this, along with a small but growing manufacturing base, helped the Soviet Union avoid any kind of balance of payments problems.[31]

الاقتصاد الاداري (مطلع ع1930–1991)

| البلد | 1890 | 1900 | 1913 | 1925 | 1938 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| روسيا/الاتحاد السوڤيتي | 21,180 | 32,000 | 52,420 | 32,600 | 75,964 |

| ألمانيا | 26,454 | 35,800 | 49,760 | 45,002 | 77,178 |

| بريطانيا العظمى | 29,441 | 36,273 | 44,074 | 43,700 | 56,103 |

| فرنسا | 19,758 | 23,500 | 27,401 | 36,262 | 39,284 |

| Comparison between the Soviet Union and the United States economies (1989) according to 1990 CIA The World Factbook[11] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Soviet Union | United States | |

| GDP (GNP) (1989; millions $) | 2,659,500 | 5,233,300 |

| Population (July 1990) | 290,938,469 | 250,410,000 |

| GDP per capita (GNP) ($) | 9,211 | 21,082 |

| Labor force (1989) | 152,300,000 | 125,557,000 |

| Sector (distribution of Soviet workforce) | 1940 | 1965 | 1970 | 1979 | 1984 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary (agriculture and forestry) | 54% | 31% | 25% | 21% | 20% |

| Secondary (including construction, transport and communication) | 28% | 44% | 46% | 48% | 47% |

| Tertiary (including trade, finance, health, education, science and administration) | 18% | 25% | 29% | 31% | 33% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

انظر أيضاً

- عام

- 1965 Soviet economic reform

- 1973 Soviet economic reform

- 1979 Soviet economic reform

- اقتصادات الكتلة الشرقية

- Enterprises in the Soviet Union

- تاريخ الاتحاد السوڤيتي

- Material balance planning

- Soviet-type economic planning

- هيئات

- العصر بعد السوڤيتي

- تصانيف الاقتصاد السوڤيتي

References

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش Soviet Union Economy 1991. 1992. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ أ ب GDP – Million 1990. 1991. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ GDP – Million 1991. KayLee. 1992. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ GDP Per Capita 1990. 1991. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Inflation Rate % 1991. 1992. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Alexeev, Michael V. "Income Distribution in the USSR in the 1980s" (PDF). Review of Income and Wealth (1993). Indiana University. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ Labor Force 1991. 1992. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Exports Million 1991. 1992. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Imports Million 1991. 1992. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Budget External Debt Million 1991". CIA Factbook. 1992. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ^ أ ب "1990 CIA World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ^ Budget Revenues Million Million 1991. 1992. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Budget Expenditures Million 1991. 1992. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Hanson, Philip (2003). The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Economy (Routledge). pp. 1–8.

- ^ Davies 1998, p. 1, 3.

- ^ Peck 2006, p. p. 47.

One notable person in this regard was Nehru, "who visited the Soviet Union in the late 1920s and was deeply impressed by Soviet industrial progress." See Bradley 2010, pp. 475–476. - ^ Allen 2003, p. 153.

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ^ Harrison 1996, p. 123.

- ^ Davies 1998, p. 2.

- ^ Daniel Yergin, The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World (2011); quotes on pp 23, 24.

- ^ Boughton 2012, p. 288.

- ^ Angus Maddison, The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective (2001) pp. 274, 275, 298.

- ^ "Japan's IMF nominal GDP Data 1987 to 1989 (October 2014)".

- ^ Vladimir G. Treml and Michael V. Alexeev, "THE SECOND ECONOMY AND THE DESTABILIZING EFFECT OF ITS GROWTH ON THE STATE ECONOMY IN THE SOVIET UNION : 1965-1989", BERKELEY-DUKE OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON THE SECOND ECONOMY IN THE USSR, Paper No. 36, December 1993

- ^ Smolinski 1973, pp. 1189–90: "The mathematical sophistication of the tools actually employed was limited to those that had been used in Das Kapital: the four arithmetical operations, percentages, and arithmetic (but not geometric) mean."

- ^ "Георгий Маленков. 50 лет со дня отставки", Radio Liberty

- ^ Пыжиков А. В. Хрущевская "Оттепель" : 1953—1964, Olma-Press, 2002 ISBN 978-5224033560

- ^ the IMF (1991). A Study of the Soviet economy. Vol. 1. International Monetary Fund (IMF). p. 287. ISBN 92-64-13468-9.

- ^ Dyker 1992, p. 2.

- ^ أ ب ت Dyker, David A. (1992). Restructuring the Soviet Economy. Routledge (published 2002). p. 3. ISBN 9781134917464. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

Repudiation of the international debts of the tsarist regime, coupled with the difficult economic conditions of the post-Wall Street crash period, ensured that any increase in the rate of accumulation would have to be internally financed. [...] In some ways, then, the Soviet Union c. 1930 was a typical developing country, with a relatively low level of accumulation and substantial surplus agricultural population. But she could not count on large-scale capital transfer from abroad – for better or worse.

- ^ Rempel, Richard A.; Haslam, Beryl, eds. (2000). Uncertain Paths to Freedom: Russia and China, 1919–22. Collected papers of Bertrand Russell. Vol. 15. Psychology Press. p. 529. ISBN 9780415094115. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

French creditors were owed forty-three percent of the total Russian debt repudiated by the Bolsheviks on 28 January 1918.

- ^ "Paul Bairoch".

- ^ Maddison, Angus (2006). The world economy (PDF). Paris, France: Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). pp. 400–600. ISBN 92-64-02261-9.

- ^ Maddison, Angus (2006). The world economy(Updated with 2018(rgdpnapc) data) (PDF). Paris, France: Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). pp. 400–600. ISBN 92-64-02261-9.

Works cited

- Allen, Robert C. (2003). Farm to Factory: A Reinterpretation of the Soviet Industrial Revolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Boughton, James M. (2012). Tearing Down Walls: The International Monetary Fund, 1990–1999. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. ISBN 978-1-616-35084-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bradley, Mark Philip (2010). "Decolonization, the global South, and the Cold War, 1919–1962". In Melvyn P. Leffler and Odd Arne Westad, eds., The Cambridge History of the Cold War, Volume 1: Origins (pp. 464–485). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83719-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, R.W. (1998). Soviet Economic Development from Lenin to Khrushchev. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harrison, Mark (1996). Accounting for War: Soviet Production, Employment, and the Defense Burden, 1940–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Moss, Walter Gerald (2005). A History Of Russia, Volume 2: Since 1855 (2nd ed.). London: Anthem Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peck, James (2006). Washington's China: The National Security World, the Cold War, and the Origins of Globalism. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smolinski, Leon (1973). "Karl Marx and Mathematical Economics". Journal of Political Economy. 81 (5): 1189–1204. doi:10.1086/260113. JSTOR 1830645.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Further reading

- Daniels, Robert Vince (1993). The End of the Communist Revolution. London: Routledge.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, R. W. ed. From Tsarism to the New Economic Policy: Continuity and Change in the Economy of the USSR (London, 1990).

- Davies, R. W. ed. The Economic Transformation of the Soviet Union, 1913–1945 (Cambridge, 1994).

- Goldman, Marshall (1994). Lost Opportunity: Why Economic Reforms in Russia Have Not Worked. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Gregory, Paul; Stuart, Robert (2001). Soviet and Post Soviet Economic Structure and Performance (7th ed.). Boston: Addison Wesley.

- Harrison, Mark. "The Soviet Union after 1945: Economic Recovery and Political Repression," Past & Present (2011 Supplement 6) Vol. 210 Issue suppl_6, p. 103–120.

- Goldman, Marshall (1991). What Went Wrong With Perestroika. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (New York: Random House, 1987).

- Pravda, Alex (2010). "The collapse of the Soviet Union, 1990–1991". In Leffler, Melvyn P.; Westad, Odd Arne (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Cold War, Volume 3: Findings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 356–377.

- Rutland, Robert (1985). The Myth of the Plan: Lessons of Soviet Planning Experience. London: Hutchinson.

In Russian

- Kara-Murza, Sergey (2004). Soviet Civilization: From 1917 to the Great Victory (in Russian) Сергей Кара-Мурза. Советская цивилизация. От начала до Великой Победы. ISBN 5-699-07590-9.

- Kara-Murza, Sergey (2004). Soviet Civilization: From the Great Victory Till Our Time (in Russian). Сергей Кара-Мурза. Советская цивилизация. От Великой Победы до наших дней. ISBN 5-699-07591-7.

External links

- Andre Gunder Frank. "What Went Wrong in the 'Socialist' East?".

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2010

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2015

- All pages needing factual verification

- Wikipedia articles needing factual verification from April 2018

- Economy of the Soviet Union

- Economies by former country

- Former communist economies

- جماعية