شمس الدين إلتـُتـْمـِش

| شمس الدين إلتـُتـْمـِش | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| سلطان دلهي | |||||

ضريح إلتتمش | |||||

| 3rd Sultan of Delhi | |||||

| العهد | 1210–1236 | ||||

| سبقه | أرام شاه | ||||

| تبعه | ركن الدين فيروز | ||||

| وُلِد | Central Asia Ilbari Turkic tribe | ||||

| توفي | 1 مايو 1236 دلهي، سلطنة دلهي | ||||

| المدفن | |||||

| Spouse | Turkan Khatun, a daughter of Qutub-ud-din Aibak (Chief consort)[1][بحاجة لمصدر غير رئيسي] Malikah-i-Jahan[2][بحاجة لمصدر غير رئيسي] | ||||

| الأنجال | Nasiruddin Mahmud Raziya Sultana Muiz ud din Bahram Ruknuddin Firuz Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah (possibly a grandson[3][4]) Ghiyasuddin Muhammad Shah[5] Jalaluddin Masud Shah[6] Shihabuddin Muhammad [7] Qutbuddin Muhammad [8] unnamed daughter[9] Shazia Begum [10][بحاجة لمصدر غير رئيسي] | ||||

| |||||

| الأسرة المالكة | سلطنة دلهي المملوكية | ||||

| الأب | إلام خان | ||||

| الديانة | الإسلام | ||||

شمس الدين إلتـُتـْمـِش بالإنجليزية Iltutmish ؛ بالهندي: अलतामश)، هو ثالث سلطان مسلم من سلاطين المماليك في الهند ، تولى الحكم في الفترة (1211–1236). [11]. وهو زوج إبنة السلطان قطب الدين أيبك مؤسس دولة المماليك في الهند.

Sold into slavery as a young boy, Iltutmish spent his early life in Bukhara and Ghazni under multiple masters. In the late 1190s, the Ghurid slave-commander Qutb ud-Din Aibak purchased him in Delhi, thus making him the slave of a slave. Iltutmish rose to prominence in Aibak's service, and was granted the important iqta' of Badaun. His military actions against the Khokhar rebels in 1205–1206 gained attention of the Ghurid ruler Muhammad of Ghor, who manumitted him even before his master Aibak was manumitted.

After Muhammad of Ghor's assassination in 1206, Aibak became a practically independent ruler of the Ghurid territories in India, with his headquarters at Lahore. After Aibak's death, Iltutmish dethroned his unpopular successor Aram Shah in 1211, and set up his capital at Delhi. He then consolidated his rule by subjugating several dissidents, and fighting against other former Ghurid slaves, such as Taj al-Din Yildiz and Nasir ad-Din Qabacha. During 1225–1227, he subjugated Aibak's former subordinates who had carved out an independent kingdom headquartered at Lakhnauti in eastern India. He also asserted his authority over Ranthambore (1226) and Mandore (1227), whose Hindu chiefs had declared independence after Aibak's death.

In the early 1220s, Iltutmish had largely stayed away from the Indus Valley region, which was embroiled in conflicts between Qabacha, the Khwarazmian dynasty, and the Mongols. In 1228, he invaded the Indus Valley region, defeated Qabacha, and annexed large parts of Punjab and Sindh to his empire. Subsequently, the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mustansir recognized his authority in India. Over the next few years, Iltutmish suppressed a rebellion in Bengal, captured Gwalior, raided the Paramara-controlled cities of Bhilsa and Ujjain in central India, and expelled Khwarazmian subordinates in the north-west. His officers also attacked and plundered the Chandela-controlled Kalinjar area.

Iltutmish organized the administration of the Sultanate, laying the foundation for its dominance over northern India until the Mughal invasion. He introduced the silver tanka and the copper jital – the two basic coins of the Sultanate period, with a standard weight of 175 grains. He set up the Iqtadari system: division of empire into Iqtas, which were assigned to the nobles and officers in lieu of salary. He erected many buildings, including mosques, khanqahs (monasteries), dargahs (shrines or graves of influential people) and a reservoir (hawz) for pilgrims.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الأسماء والألقاب

The name "Iltutmish" literally means "maintainer of the kingdom" in Turkic. Since vowel marks are generally omitted in the historical Persian language manuscripts, different 19th-20th century writers read Iltutmish's name variously as "Altamish", "Altamsh", "Iyaltimish", and "Iletmish".[12] However, several verses by contemporary poets, in which the Sultan's name occurs, rhyme properly only if the name is pronounced "Iltutmish". Moreover, a 1425-1426 (AH 829) Tajul-Ma'asir manuscript shows the vowel "u" in the Sultan's name, which confirms that "Iltutmish" is the correct reading of the name.[13]

Iltutmish's inscriptions mention several of his grandiloquent titles, including:[14]

- Maula muluk al-arab wa-l-ajam ("King of the Kings of the Arabs and the Persians"), a title used by earlier Muslim kings including the Ghaznavid ruler Mas'ud

- Maula muluk al-turk wa-l'ajam, Saiyid as-salatin al-turk wa-l'ajam, Riqab al-imam maula muluk al-turk wa-l-ajam ("Master of Kings of the Turks and the Persians")

- Hindgir ("Conqueror of Hind")

- Sultan Salatin ash-Sharq ("the Sultan of the Sultans of the East")

- Shah-i-Sharq ("King of the East")

- Shahanshah ("King of Kings"), a title of the emperors of Persia

In Sanskrit language inscriptions of the Delhi Sultanate, he has been referred to as "Lititmisi" (a rendering of "Iltutmish"); Suritan Sri Samasadin or Samusdina (a rendering of his title "Sultan Shamsuddin"); or Turushkadhipamadaladan ("the Turushka Lord").[15]

النشأة

خارج الهند

Iltutmish was born in an affluent family: his father Ilam Khan was a leader of the Ilbari Turkic tribe. According to Minhaj's Tabaqat-i Nasiri, he was a handsome and intelligent boy, because of which his brothers grew jealous of him; these brothers sold him to a slave dealer at a horse show. Minhaj's narrative appears to be inspired by the Quranic story of Hazrat Yusuf (Joseph), who was sold into slavery by his jealous brothers.[16]

According to Minhaj, as a young boy, Iltutmish was brought to Bukhara, where he was re-sold to the local Sadr-i Jahan (officer in charge of religious matters and endowments). There are several anecdotes about Iltutmish's childhood interest in religious mysticism. According to a story narrated by Iltutmish himself in Minhaj's book, once a family member of the Sadr-i Jahan gave him some money and asked him to bring some grapes from the market. Iltutmish lost the money on the way to the market, and started crying fearing punishment from his master. A dervish (Sufi religious leader) noticed him, and bought the grapes for him in exchange for a promise that he would treat religious devotees and ascetics well upon becoming powerful.[17] The writings of Isami and some other sources suggest that Iltutmish also spent some time in Baghdad, where he met noted Sufi mystics such as Shahab al-Din Abu Hafs Umar Suhrawardi and Auhaduddin Kermani.[17]

Minhaj states that the family of Sadr-i Jahan treated Iltutmish well, and later sold him to a merchant called Bukhara Haji. Iltutmish was subsequently sold to a merchant called Jamaluddin Muhammad Chust Qaba, who brought him to Ghazni. The arrival of a handsome and intelligent slave in the town was reported to the Ghurid king Mu'izz ad-Din, who offered 1,000 gold coins for Iltutmish and another slave named Tamghaj Aibak. When Jamaluddin refused the offer, the king banned the sale of these slaves in Ghazni. A year later, Jamaluddin went to Bukhara, and stayed there for three years with the slaves.[17]

في خدمة قطب الدين

Subsequently, Iltutmish's master Jamaluddin returned to Ghazni, where Mu'izz ad-Din's slave-commander Qutb al-Din Aibak noticed Iltutmish.[17] Qutb al-Din, who had just returned from a campaign in Gujarat (c. 1197), sought Mu'izz ad-Din's permission to purchase Iltutmish and Tamghaj. Since their sale had been banned in Ghazni, Mu'izz ad-Din directed them to be taken to Delhi. In Delhi, Jamaluddin sold Iltutmish and Tamghaj to Qutb al-Din for 100,000 jitals (silver or copper coins). Tamghaj rose to the position of the muqta (provincial governor) of Tabarhinda (possibly modern Bathinda), while Iltutmish became the sar-jandar (head of bodyguard).[18]

Iltutmish rose rapidly in Qutb al-Din's service, attaining the rank of Amir-i Shikar (superintendent of the hunt). After the Ghurid conquest of Gwalior in 1200, he was appointed the Amir of the town, and later, he was granted the iqta' of Baran. His efficient governance prompted Qutb al-Din to grant him the iqta' of Badaun, which according to Minhaj, was the most important one in the Delhi Sultanate.[18]

In 1205–1206, Sultan Mu'izz ad-Din summoned Qutb al-Din's forces for his campaign against the Khokhar rebels. During this campaign, Iltutmish's Badaun contingent forced the Khokhars into the middle of the Jhelum river, and killed them there. Mu'izz ad-Din noticed Iltutmish, and made inquiries about him.[18] The Sultan subsequently presented Iltutmish with a robe of honour, and asked Aibak to treat him well. Minhaj states that Mu'izz ad-Din also ordered Iltutmish's deed of manumission to be drawn on this occasion, which would mean that Iltutmish - a slave of a slave until this point - was manumitted even before his own master Aibak had been manumitted. However, Iltutmish's manumission doesn't appear to have been well-publicized because Ibn Battuta states that at the time of his ascension a few years later, an ulama deputation led by Qazi Wajihuddin Kashani waited to find if he had obtained a deed of manumission or not.[19]

المماليك في الهند

يعد التمش المؤسس الحقيقي لدولة المماليك بالهند ، وهو في الأصل مملوك اشتراه السلطان قطب الدين أيبك من غزنة ، ومكنتّه مواهبه من تولي المناصب الكبيرة، وحظي بثقة سيده؛ فولاه رئاسة حرسه، ثم عهد إليه بإدارة بعض الولايات الهندية.

حكمه

تعرض ألتمش لمشاكل داخلية إثر توليه السلطة ولكنه استطاع التغلب عليها، خرج عليه تاج الدين يلدز واستقل بحكم غزنة، كما خرج عليه غياث الدين الخلجي ـ والي البنغال من قبله ـ أكثر من مرة وأعلن استقلاله عن دلهي، وكذلك فعل ناصر الدين قباجة، ولكن ألتتمش تمكن من القضاء عليهم. واكتسب حكمه الصفة الشرعية حينما أرسل إليه الخليفة العباسي المنتصر بالله تقليدًا بحكم دولة الإسلام في الهند سنة 626هـ، 1228م، وكان لهذا الإجراء أثره الكبير في تقوية دولته، فخرج للقضاء على خصومه من راجات الهند الذين انتهزوا فرصة انشغاله بمشاكله الداخلية فاستقلوا ببلدانهم، فانتصر عليهم وأعاد ما سلبوه منه.

وما إن أمسك إلتتمش بمقاليد الأمور في البلاد حتى كشف عن كفاءة نادرة وقدرة على الإدارة والتنظيم، ورغبة في إقامة العدل وإنصاف المظلومين، فينسب إليه أنه قام بتأسيس مجلس من كبار أمراء المماليك عُرف باسم "الأربعين" لمعاونته في إدارة البلاد، ويُؤثَر عنه أنه أمر أن يلبس كل مظلوم ثوبا مصبوغا، وكان أهل الهند جميعا يلبسون الأبيض، فإذا قعد للناس أو مرّ على جمع من الناس، فرأى أحدا يرتدي ثوبا مصبوغا؛ نظر في قضيته وأنصفه ممن ظلمه.

السنوات اللاحقة

اعتراف الخليفة العباسي به

وبلغ الفوز مداه بأن اعترفت الخلافة العباسية بولايته على الهند، وأقرّته سلطانا على البلاد، وبعث له الخليفة المستنصر بالله العباسي بالتقليد والخلع والألوية في سنة (626هـ= 1229 م) فأصبح أول سلطان في الهند يتسلم مثل هذا التقليد، وبدأ في ضرب نقود فضية نُقش عليها اسمه بجوار اسم الخليفة العباسي، فكانت أول نقود فضية عربية خالصة تُضرب في الهند. [20]

In 1220-, the Abbasid Caliph Al-Nasir sent his Indian-born ambassador Radi al-Din Abu'l-Fada'il al-Hasan bin Muhammad al-Saghani to Delhi.[21][22] The ambassador returned to the Abbasid capital Baghdad in 1227, during the reign of Al-Mustansir. In 1228, the new Caliph sent the ambassador back to Delhi with robes of honour, recognizing Iltutmish's authority in India and conferring on him the titles Yamin Khalifat Allah ("Right Hand of the God's Deputy") and Nasir Amir al-Mu'minin ("Auxiliary of the Commander of the Faithful").[23] On 18 February 1229, the embassy arrived in Delhi with a deed of investiture.[22]

Although the Caliphate's status as a pan-Islamic institution had been declining, the Caliph's recognition was seen as a religious and political legitimization of Iltutmish's status as an independent ruler rather than a Ghurid subordinate.[24][25] The Caliph's recognition was a mere formality, but Iltutmish celebrated it in a big way, by decorating the city of Delhi and honouring his nobles, officers, and slaves.[22] Iltutmish's own court poets eulogize the event,[26] and the 14th century Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta describes him as the first independent ruler of Delhi.[15] Iltutmish is the only ruler of India to have the Caliph's recognition. Ghiyasuddin Iwaj Shah, the ruler of Bengal defeated by Iltutmish's forces, had earlier assumed the title Nasir Amir al-Mu'minin, but he did so unilaterally without the Caliph's sanction. The Caliph probably saw Iltutmish as an ally against his Khwarazmian rival, which may have prompted him to recognize Iltutmish's authority in India.[21]

After the Caliph's recognition, Iltutmish began inscribing the Caliph's name on his coins, including the new silver tanka introduced by him.[26]

الحملات الأخرى

In March–April 1229, Iltutmish's son Nasiruddin Mahmud, who had been governing Bengal since 1227, died unexpectedly. Taking advantage of this, Malik Balkha Khalji, an officer of Iltutmish, usurped the authority in Bengal. Iltutmish invaded Bengal, and defeated him in 1230.[21][27] He then appointed Malik Alauddin Jani as the governor of Bengal.[27]

Meanwhile, Mangal Deva, the Parihara chief of Gwalior in central India, had declared independence. In 1231, Iltutmish besieged the city, and captured it after 11 months of conflict, on 12 December 1232. After Mangal Deva fled, and Iltutmish left the fort under the charge of his officers Majdul Mulk Ziyauddin.[27]

In 1233–1234, Iltutmish placed Gwalior under Malik Nusratuddin Taisi, who was also assigned the iqta's of Sultankot and Bayana, and made in-charge of the military contingents at Kannauj, Mehr, and Mahaban. Shortly after, Taisi attacked the Chandela fort of Kalinjar, and subsequently plundered the area for around 50 days. During this campaign, he acquired a large amount of wealth: Iltutmish's share (one-fifth) of the loot amounted to 2.5 million jitals.[28] While Taisi was returning to Gwalior, the Yajvapala ruler Chahada-deva (called Jahar by Minhaj) ambushed him, but Taisi able to fend off the attack by dividing his army into three contingents.[29]

Subsequently, Iltutmish raided the Paramara-controlled cities of Bhilsa and Ujjain in 1234–35.[30] Iltutmish's army occupied Bhilsa, and destroyed a temple whose construction - according to Minhaj - had taken three hundred years.[31] At Ujjain, his forces damaged the Mahakaleshwar temple and obtained rich plunder, but made little effort to annex the Paramara territory.[32] The jyotirlinga at the site was dismantled and believed to be thrown into a nearby 'Kotiteerth Kunda' (a pond neighboring the temple) with the Jaladhari (a structure supporting the Lingam) stolen during the invasion.[33]

By 1229–1230, the north-western boundary of Iltutmish's kingdom appears to have extended up to the Jhelum River, as Nasawi states that he controlled the area "up to the neighbourhood of the gates of Kashmir". During this period, Iltutmish invaded the territories controlled by the Khwarazmian subordinate Ozbeg-bei, in present-day Pakistan. Ozbeg-bei fled to the Khwarazmian ruler Jalal-ad-Din in Iraq, while Other local commanders - including Hasan Qarluq - surrendered to Iltutmish. Qarluq later changed his allegiance to the Mongols. During his last days, in 1235–1236, Iltutmish is known to have aborted a campaign in the Binban area: this campaign was probably directed against Qarluq.[34]

Hammira-mada-mardana, a Sanskrit play by Jayasimha Suri, mentions that a mlechchha (foreigner) called Milachchhrikara invaded Gujarat during the Chaulukya reign. The Chaulukya minister Vastupala used diplomatic tactics to create many difficulties for the invader, who was ultimately defeated by the general Viradhavala. Some historians have identified Milachchhrikara with Iltutmish, thus theorizing that Iltutmish unsuccessfully tried to invade Gujarat. However, others have dismissed this identification as inaccurate.[35]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

خطر المغول والوفاة

وقد عاصر إلتتمش اجتياح المغول المدمّر لما حولهم من البلاد بقيادة زعيمهم جنكيز خان، غير أن المغول انسحبوا سريعا من الهند، واتجهت أبصارهم نحو الغرب؛ فنجت بلاد التمش من الخراب والدمار، في حين تكفّل هذا الإعصار المغولي بالقضاء على أعداء دولته في الشمال؛ الأمر الذي مكّنه من توسيع رقعة بلاده، وأن يستعيد جميع ممتلكات سيده "قطب الدين أيبك" في شمال الهند.

In 1236, Iltutmish fell ill during a march towards Qarluq's stronghold of Bamyan, and returned to Delhi on 20 April, at the time chosen by his astrologers. He died in Delhi shortly after, on 30 April 1236.[31] He was buried in the Qutb complex in Mehrauli.[36]

- Illtumish's tomb in Qutub Minar Complex

The death of Iltutmish was followed by years of political instability at Delhi. During this period, four descendants of Iltutmish were put on the throne and murdered.[37] In the 1220s, Iltutmish had groomed his eldest son Malikus Sa'id Nasiruddin Mahmud as his successor, but Nasiruddin died unexpectedly in 1229. While leaving for his Gwalior campaign in 1231, Iltutmish had left Delhi's administration to his daughter Razia. Her effective administration prompted him to declare her as his heir apparent in 1231, upon his return from Gwalior.[38] However, shortly before his death, Iltutmish seems to have chosen his surviving eldest son Ruknuddin Firuz as his successor. When Iltutmish died, the nobles unanimously appointed Ruknuddin as the new king.[39]

During Ruknuddin's reign, his mother Shah Turkan took control of the state affairs, and started mistreating her rivals. Their execution of Qutubuddin, a popular son of Iltutmish, led to rebellions by several nobles, including Malik Ghiyasuddin Muhammad Shah - another son of Iltutmish.[40] Amid these circumstances, Razia seized the throne in November 1236, with support of the general public and several nobles, and Ruknuddin was executed.[41] Razia also faced rebellions, and was deposed and killed in 1240.[42] The nobles then appointed Muizzuddin Bahram - another son of Iltutmish - on the throne, but subsequently deposed and killed him in 1242.[43] Next, the nobles placed Ruknuddin's son Alauddin Masud on the throne, but he too, was deposed in 1246.[44]

Order was re-established only after Nasiruddin-Mahmud became Sultan with Iltutmish's prominent slave, Ghias-ud-din-Balban as his deputy (Naib) in 1246.[45] Minhaj calls the new Sultan a son of Iltutmish, but Isami and Firishta suggest that he was a grandson of Iltutmish. Some modern historians consider Minhaj more reliable,[46] while others believe that the new Sultan was a son of Iltutmish's eldest son Nasiruddin (who died before Iltutmish), and was named after his father.[3][4] Balban held all the power at the time and became Sultan in 1266.[45] Balban's descendants ruled Delhi until they were overthrown by the Khaljis.

الدين والذكرى

توفي ألتمش بعد أن وطَّد نفوذه وسلطانه في دولة المماليك في الهند، وترك تنظيمًا إداريًا قويًا، وأرسى مبادئ العدالة. وأنفق أموالاً ضخمة في كتابة نسخ كثيرة من القرآن الكريم، وأسس العديد من المدارس وزيّن بلاطه بالشعراء والعلماء، وجعل عاصمته مركزًا مهمًا للعلوم والآداب، وأولى الفن المعماري عناية كبيرة، فأتم بناء مسجد قطب الدين أيبك في دلهي، وشيد مسجدًا آخر في أجمير.

Iltutmish was a devout Muslim, and spent considerable time praying at night.[47]

He was punctual in offering his prayers.

Nizam-ud-Din Ahmad says:

Sultan Shams-ud-Din was very puntilious in his prayers (namaz) and on Fridays he went to the mosque and stayed there to offer obligatory and superogatory prayers.[48]

He also made special arrangement for prayers on military campaigns.

His court poet Amir Ruhani describes him as a "holy warrior and Ghazi".[49] He revered several Sufi saints, including Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki, Hamiduddin Nagauri, Jalaluddin Tabrizi, Bahauddin Zakariya, and Najibuddin Nakhshabi.[47]

Policy towards Hindus

When a group of ulema came to Iltutmish and requested him to apply the law of “death or Islam” on Hindus, Iltutmish asked Nizam-ul’-Mulk Junaidi to give a suitable reply to the ulama.

The Wazir replied to them:

“But at the moment India has newly been conquered and the Muslims are so few that they are like salt (in a large dish). If the above orders are to be applied to the Hindus, it is possible they might combine and a general confusion might ensue and the Muslims would be too few in number to suppress this general confusion. However, after a few years when in the capital and in the regions and the small towns the Muslims are well established and the troops are larger, it will be possible to give Hindus, the choice of “death or Islam”".[50]

Iltutmish held religious discourses by orthodox ulama - such as Sayyid Nuruddin Mubarak Ghaznavi - in his court, but disregarded their advice while formulating the imperial policies.[47] He understood the limits to which the Islamic shariah law could be implemented in largely non-Muslim India. He did not consult the ulama while making the unorthodox decision of nominating his daughter Raziya as his successor.[47] This balance between the shariah and the practical needs of the time became a feature of Turkic rule in Delhi.[51]

الذكرى

"Iltutmish laid down the foundation of the Delhi Sultanate as a truly independent kingdom, freeing it from a subordinate position to Ghazni.[32][52] The Caliph's investiture, although a mere formality, reaffirmed his status as an independent sovereign among the Muslims.[32] By the time of his death, the Delhi Sultanate had emerged as the largest and the most powerful kingdom in northern India.[52]

Iltutmish was most probably the first ruler to organize a centrally recruited, centrally paid and centrally managed army in the Delhi Sultanate. His courtier Fakhr-i Mudabbir composed Adab al-harb wa-l-shaja'a, a book on the art of warfare.[53]

الإقطاعات

Iltutmish implemented the iqta system of administrative grants in the Delhi Sultanate. This system, borrowed from the earlier Islamic dynasties of the Middle East, involved dedicating the revenues from a certain region to a subordinate in exchange for military service and political loyalty. Iltutmish used this iqtas to consolidate his empire by dismantling the existing feudal order of the Indian society.[54]

Iltutmish assigned several regions to his Turkic subordinates in form iqtas. The larger iqtas - which were effectively provinces of the empire - were assigned to high-ranking men, who were expected to administer the regions, maintain local law and order, and supply military contingents in times of need. The holders of the smaller iqtas were only expected to collect revenues from their regions, in exchange for providing military service to the emperor. To ensure that this iqta system remained bureaucratic - rather than feudal - in nature, Iltutmish transferred the iqta holders from one region to another, refused to grant them legal immunity, and discouraged localism in administration.[53]

Both free amirs as well as bandagan-i-shamsi (as opposed to bandagan-i-khass during Mu'izz ad-Din's times) were used by Iltutmish over an extended, long process involving rotation of the iqtas assigned to each noble every once in a while to ensure that there was no question of claims on a specific region by a specific noble. Besides these, princes were used as well in almost the same capacity, but in more important roles.[55][صفحة مطلوبة]

العملات

Iltutmish introduced two coins that became the basis for the subsequent coinage of the Delhi Sultanate: the silver tanka and the copper jital.[56]

His predecessors, including the Ghurid rulers, had maintained the local coinage system based on the Hindushahi bull-and horseman coins minted at Delhi. Dehliwala, the standard coin, was a silver-copper alloy with a uniform weight of 3.38 grams, of which 0.59 grams was Silver. The major source of silver for the Delhi mint were coin hoards from Central Asia. Another source was European silver which made its way to Delhi via the Red Sea, Persian Gulf through the ports of Gujarat. By the 1220s, supply from Central Asia had dried up and Gujarat was under control of hostile forces.[57]

- Coins of Iltutmish

Obv: Crude figure of Rider bearing lance on caparisoned horse facing right. Devanagari legends: Sri / hamirah. Star above horse.

Rev: Arabic legends: Shams al-dunya wa'l din Iltutmish al-sultan.

In response to the lack of silver, Iltutmish introduced a new bimetallic coinage system to Northern India consisting of an 11 grams silver tanka and the billon jital, with 0.25 grams of silver. The Dehliwala was devalued to be on par with the jital. This meant that a Dehliwala with 0.59 grams of silver was now equivalent to a coin with 0.25 grams of silver. Each Dehliwala paid as tax, therefore produced an excess 0.34 grams of silver which could be used to produce tankas. The new system served as the basis for coinage for much of the Sultanate period and even beyond, though periodic shortages of silver caused further debasement. The tanka is a forerunner to the Rupee.[58][59]

الثقافة الإسلامية

During Iltutmish's reign, the city of Delhi emerged as the centre of Islamic power and culture in India.[52] He patronized several scholars, including historian Minhaj-i-Siraj and the Sufi mystic Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki.[51] Minhaj states that Iltutmish's patronage attracted several scholars and other prominent people to Delhi, especially from Persia, which had fallen to the Mongols.[60] Iltutmish's court is reported to have had raised seats for distinguished scholars and saints, as opposed to lower seats for others. This is suggested by Fawa'id-ul-Fu'ad, a near-contemporary work, which describes a quarrel between Shaikh Nizamuddin Abul Muwayyid and Sayyid Nuruddin Mubarak Ghaznavi over choice of seats in Iltutmish's presence.[47]

Fawa'id-ul-Fu'ad mentions an anecdote about Iltutmish's patronage to scholars: Nasiri, a poet in need of a royal award, composed a qasida in praise of Iltutmish. However, while he was in the middle of reciting the poem, Iltutmish left the recital to attend an urgent administrative matter. A dismayed Nasiri thought Iltutmish would forget him, and lost all hope of getting the royal award. But as soon as Iltutmish was free, he came to Nasiri, recited the first line of the qasida from his memory, and asked Nasiri to complete his recital.[61]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

العمارة

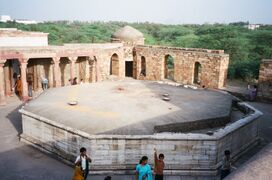

Iltutmish invested in numerous waterworks, mosques, and civil amenities in Delhi.[51] He completed the construction of the Qutb Minar, which had been started by Qutb al-din Aibak. He also commissioned the Hauz-i-Shamsi reservoir to the south of Qutb Minar, and the madrasa (school) around it.[62]

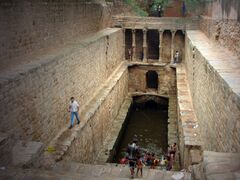

He built several khanqah (monasteries) and dargahs (graves) for Sufi saints.[بحاجة لمصدر] He commenced the structure of Hamid ud-din's Khanaqa, and built the Gandhak ki Baoli, a stepwell for the Sufi saint, Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki, who moved to Delhi during his reign.[63]

In 1231, he built the Sultan Ghari funerary monument for his eldest son Nasiruddin, who had died two years earlier.[64] This was the first Islamic mausoleum in Delhi, and lies within fortified grounds, which also include the graves of other relatives of Iltutmish.[65]

Qutb Minar was completed by Iltutmish

Hauz-i-Shamsi pavilion

العائلة

الجواري

- Turkan Khatun (died after 1236; also known as Turkman Khatun or Qutub Begum), was the chief consort of Iltutmish and daughter of Qutb ud-Din Aibak. She was the mother of Nasiruddin Mahmud, Razia Sultana, Ghiyasuddin Muhammad Shah, Shihabuddin Muhammad, Shazia Begum and Qutbuddin Muhammad. She was probably the youngest daughter of Qutbuddin Aibak while her two other sisters were married to Nasir ad-Din Qabacha.[66]

- Shah Turkan (probably died after 1236), was the Khudawanda (concubine) of Iltutmish and mother of Ruknuddin Firuz. She was the first royal lady taking active part in political matters during the Slave Dynasty. Turkan had been a Turkic (enslaved) hand-maid and had risen to take control of the Sultan's harem. She took this opportunity to wreak vengeance against all those who had slighted her in the past.

- Mother of Muizuddin Bahram (died after 1236), not much known about her but she was the mother of Sultan Muizuddin Bahram and a daughter, who married to Malik Ikhtiyar uddin Aitegin. She probably the daughter or sister of one of Iltutmish's forty chiefs.

- Malika-i-Jahan (died after 1246; full title: Malika-i-Jahan Jalal ud Dunya wal Din), mother of Sultan Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah. Her real name was unknown, formerly the concubine of Iltutmish but she was given the title Malika-i-Jahan during his son's reign. Her existence as Iltutmish's consort often debate, some stated she was the wife of Iltutmish's deceased son, Malik-us-Sa'id Nasiruddin Mahmud. Both she and her son was sent to live in a palace in Loni Village. After the death of Iltutmish, she married Malik Saifuddin Qutlugh Khan.[67]

- Mother of Jalaluddin Masud Shah, unknown identity.

- Many other concubine;

أبناؤه

- Malik-us-Sa'id Nasiruddin Mahmud (died 1229) –with Turkan Khatun;[68] an eldest son of Iltutmish, who he grommed as his successor but unexpected died in 1229. He was the governor of Oudh later served as governor of Bengal until his death in 1229. He sent by Iltutmish to lead an invasion against the rebel Iwaz Khalji.[69] After defeating Iwaz Khalji, he received the title Malik-ush-Sharq (مٰلك الشّرق Māliku ’sh-Sharq, Arabic: "King of the East") from his father.

- Sultan Ruknuddin Firuz (executed 19 November 1236) –with Shah Turkan;[70] he was appointed as successor of Iltutmish. However he spent his time in pursuing pleasure and left his mother in control the administration. The misadministration led to rebellions against Ruknuddin and his mother.[71]

- Sultan Muizuddin Bahram Shah (killed by the rebels in 15 May 1242), –with unnamed consort. He declared himself as a new King with the support of forty chiefs when his sister Razia Sultana was imprisoned in Bathinda and also appointed Amir-i-Hajib Malik Ikhtiyar ud-Din Aitegin as his regent. During the rebel against him, Ikhtiyaruddin Aitegin was killed before him.

- Malik Ghiyas ud-Din Muhammad Shah (died after 1236) –probably with Turkan Khatun; he was appointed as governor of Oudh. He was rebel against Ruknuddin Firuz after Shah Turkan blinded and executed the popular son of Iltutmish, Qutbuddin.[72]

- Jalaluddin Masud Shah (died after 1242) –with unnamed consorts; Upon the death of Muiz ud din Bahram, he along with his brother Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah and nephew Ala-ud-Din Masud Shah (son if Ruknuddin Firuz) was brought to Firuzi castle, the royal residence, from the confinement of the white castle by the amirs and Ala ud din Masud was chosen as the Sultan. Both the brothers remained in confinement until September 1243.[73]

- Shihabuddin Muhammad, not much known about him. His mother probably Turkan Khatun and he probably died in childhood or executed during the reign of Ruknuddin Firuz.[74]

- Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah (c. 1229/1230 – 19 November 1266) –with Malika-i-Jahan Jalal ud Dunya wal Din;[75] He was named after his deceased eldest brother Nasiruddin Mahmud, he was sent to live in a palace in Loni Village.[76] He ascended the throne in 1246 and appointed his father-in-law Ghiyas ud din Balban as a regent.[77]

- Qutbuddin Muhammad (blinded and executed in 1236) –with Turkan Khatun; he was the youngest son of Iltutmish and popular among the statesmen. In 1236 during the reign of Ruknuddin Firuz, Shah Turkan started mistreating her rival and one of them was Qutbuddin, who had been blinded and executed. This incident led rebellion against Ruknuddin Firuz.[78]

بناته

- Razia Sultana (c. 1205 – 15 October 1240) –with Turkan Khatun;[79][80] she was the first and only female ruler of Delhi Sultanate, when her father leaving for his Gwalior campaign in 1231, Iltutmish left her as in-charge of Delhi's administration. She performed her duties so well that after his father returns, Iltutmish decided to name her as his successor.[81] She ascended the throne in 1236 but overthrown in 1240. In 1240 during the imprisonment in Bathinda, she married Malik Ikhtiyar ud-Din Altunia. Both of them were killed in October 1240.[82]

- Shazia Begum (probably died 1240) –with Turkan Khatun. not much known about her but Some sources said she was killed along with Razia and her tomb located beside Razia's grave in Mohalla Bulbuli Khanna near Turkman Gate in Old Delhi.[83] She is said to be married to a statesman known as Izz-ud-din Balban-i-Khaslu Khan.[84]

- Unnamed daughter (died after 1240) –with unnamed consorts; she was the sister of Muiz ud din Bahram, which he married the regent Amir-i-Hajib Malik-i-Kabir Ikhtiyaruddin Aitegin.[85]

المراجع

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 676.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 676.

- ^ أ ب K. A. Nizami 1992, pp. 256.

- ^ أ ب Jaswant Lal Mehta 1979, p. 105.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 625, 633.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 625, 661.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 625.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 625, 633.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 650, 661.

- ^ "Grave of Delhi's only woman Sultan lies forgotten". www.dnaindia.com. Retrieved 2022-11-06.

- ^ >Sheikh Mohamad Ikram (1966). Muslim Rule in India & Pakistan, 711-1858 A.C. Star Book Depot. p. p.52.

{{cite book}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, pp. 209–210:"There has been considerable controversy during the last several decades regarding the pronunciation and the orthography of the Sultan's name. Contemporary Persian textsTajul Ald'asir, Tarikh-iFakhruddin Mubarak Shah, Adabul Harb and Tabagat-i Nasiri-as well as the inscriptions on buildings and coins have been differently read and differently interpreted by different writers. Elphinstone spelt the name as 'Altamish;! CJliot as 'Altamsh';2 and Raverty as Tyaltimish. In 1907 Barthold suggested that the word was really IItutmish'maintainer of the kingdom' and advanced convincing arguments in support of his view"

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 209.

- ^ André Wink 1991, pp. 154-155.

- ^ أ ب André Wink 1991, p. 154.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 210.

- ^ أ ب ت ث K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 211.

- ^ أ ب ت K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 212.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 213.

- ^ إسلام أون لاين

- ^ أ ب ت Peter Jackson 2003, p. 37.

- ^ أ ب ت K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 219.

- ^ Peter Jackson 2003, pp. 37-38.

- ^ Oliver-Dee 2009, p. 31.

- ^ Blain H Auer 2012, pp. 107-108.

- ^ أ ب F. B. Flood 2009, p. 240.

- ^ أ ب ت K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 220.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 221.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, pp. 221-222.

- ^ André Wink 1991, p. 156.

- ^ أ ب K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 222.

- ^ أ ب ت Satish Chandra 2004, p. 45.

- ^ Mahajan, Vidya Dhar (1965). Muslim Rule in India (in الإنجليزية). S. Chand.

- ^ Peter Jackson 2003, p. 36.

- ^ A. K. Majumdar 1956, pp. 157-159.

- ^ S. M. Ikram 1966, p. 52.

- ^ André Wink 1991, p. 157.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 230.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 231.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 235.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 236.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 242.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, pp. 244-249.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, pp. 250-255.

- ^ أ ب Peter Jackson 2003, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Riazul Islam 2002, p. 323.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 229.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 20.

- ^ Iqtidar Husain Siddiqi 2003, p. 40.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 24.

- ^ أ ب ت Salma Ahmed Farooqui 2011, p. 60.

- ^ أ ب ت Salma Ahmed Farooqui 2011, p. 59.

- ^ أ ب K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 227.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, pp. 226-227.

- ^ Kumar, Sunil (2007). The Emergence of the Delhi Sultanate. Ranikhet: Permanent Black. ISBN 978-81-7824-306-1.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, pp. 227-228.

- ^ Ian Blanchard 2005, pp. 1263–1264.

- ^ Ian Blanchard 2005, pp. 1264–1265.

- ^ André Wink 1991, p. 155.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 223.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 228.

- ^ Satish Chandra 2004, p. 46.

- ^ Ronald Vivian Smith 2005, pp. 11-12.

- ^ R. Balasubramaniam 2005, p. 98.

- ^ Y.D.Sharma (2001). "Delhi and its Neighbourhood". Hauzi-i-Shamsi (New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India). pp. 63–64 &73. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 676.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 676.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, Abu-'Umar-i-'Usman (1873). Tabaqat-i-Nasiri. London: Asiatic Society. pp. 660–673.

- ^ Ahmed, ABM Shamsuddin (2012). "Iltutmish". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, pp. 234–235.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 236.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 625, 633.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 625, 661.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 625, 633

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873) p.676

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, pp. 256.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra (2013). Textbook of medieval Indian history. Primus Books. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-93-80607-34-4. OCLC 822894456.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 625, 633.

- ^ Guida M. Jackson 1999, p. 341.

- ^ Sudha Sharma 2016, p. 141 quote:"But as per Abu-Umar-i-Usman Minhaj-ud-din Siraj (Tabaqat-iNasiri), Turkan Khatun was the name of Razia's mother and not of this lady [Shah Turkan]."

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, pp. 230–231.

- ^ K. A. Nizami 1992, p. 243.

- ^ "Grave of Delhi's only woman Sultan lies forgotten". www.dnaindia.com. Retrieved 2022-11-06.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 650, 661.

- ^ Minhaj-i-Siraj, "Tabaqat-i-Nasiri" translated by Major HG Raverty (1873), p. 650, 661.

انظر أيضا

المصادر

| سبقه أرام شاه |

سلطان مماليك الهند 1206-1290 |

تبعه ركن الدين فيروز |

| سبقه أرام شاه |

سلطان دلهي 1206-1290 |

تبعه ركن الدين فيروز |