آني (مدينة)

The ruins of Ani as seen from the Armenian side. The cathedral with its missing dome is seen on the left, the half-collapsed Church of the Holy Redeemer on the right. | |

| المكان | Ocaklı (nearest settlement),[1][2] Kars Province, تركيا |

|---|---|

| المنطقة | Armenian Highlands |

| الإحداثيات | 40°30′27″N 43°34′22″E / 40.50750°N 43.57278°E |

| النوع | Settlement |

| التاريخ | |

| تأسس | 5th century (first mentioned) |

| هـُـجـِر | 17th century |

| الفترات | Middle Ages |

| الثقافات | Armenian (predominantly) |

| الاسم الرسمي | Archaeological Site of Ani |

| النوع | Cultural |

| المعيار | ii, iii, iv |

| التوصيف | 2016 (40th session) |

| الرقم المرجعي | 1518 |

| State Party | تركيا |

| Region | Europe and North America |

Ani (بالأرمينية: Անի; باليونانية: Ἄνιον, Ánion;[5] لاتينية: Abnicum;[6][7] بالجورجية: ანი, Ani, or ანისი, Anisi;[8] تركية: Anı)[9] is a ruined medieval Armenian city now situated in تركيا's province of Kars, next to the closed border with Armenia.

Between 961 and 1045, it was the capital of the Bagratid Armenian kingdom that covered much of present-day Armenia and eastern Turkey. Called the "City of 1001 Churches",[7][10][11] Ani stood on various trade routes and its many religious buildings, palaces, and fortifications were amongst the most technically and artistically advanced structures in the world.[12][13] At its height, Ani was one of the biggest cities in the world,[14] and its population was probably on the order of 100,000.[15][16]

Long ago renowned for its splendor and magnificence, Ani was sacked by the Mongols in 1236 and devastated in a 1319 earthquake, after which it was reduced to a village and gradually abandoned and largely forgotten by the seventeenth century.[17][16] Ani is a widely recognized cultural, religious, and national heritage symbol for Armenians.[18] According to Razmik Panossian, Ani is one of the most visible and ‘tangible’ symbols of past Armenian greatness and hence a source of pride.[16]

أصل الكلمة

The city took its name from the Armenian fortress-city and pagan center of Ani-Kamakh located in the region of Daranaghi in Upper Armenia.[15][مطلوب توضيح] Ani was also previously known as Khnamk (Խնամք), although historians are uncertain as to why it was called so.[15][مطلوب توضيح] Johann Heinrich Hübschmann, a German philologist and linguist who studied the Armenian language, suggested that the word may have come from the Armenian word "khnamel" (խնամել), an infinitive which means "to take care of".[15] Ani was also the diminutive name of ancient Armenian goddess Anahit who was seen as the mother-protector of Armenia.[بحاجة لمصدر]

الموقع

The city is located on a triangular site, visually dramatic and naturally defensive, protected on its eastern side by the ravine of the Akhurian River and on its western side by the Bostanlar or Tzaghkotzadzor valley.[6] The Akhurian is a branch of the Araks River[6] and forms part of the currently closed border between Turkey and Armenia. The site is at an elevation of around 1،340 متر (4،400 ft).[7]

التاريخ

التاريخ المبكر

Armenian chroniclers such as Yeghishe and Ghazar Parpetsi first mentioned Ani in the 5th century.[15] They described it as a strong fortress built on a hilltop and a possession of the Armenian Kamsarakan dynasty.

عاصمة باجراتوني

By the early 9th century, the former territories of the Kamsarakans in Arsharunik and Shirak (including Ani) had been incorporated into the territories of the Armenian Bagratuni dynasty.[19] Their leader, Ashot Msaker (Ashot the Meateater) (806–827) was given the title of ishkhan (prince) of Armenia by the Caliphate in 804.[20] The Bagratunis had their first capital at Bagaran, some 40 km south of Ani, before moving it to Shirakavan, some 25 km northeast of Ani, and then transferring it to Kars in the year 929. In 961, king Ashot III (953–77) transferred the capital from Kars to Ani.[7] Ani expanded rapidly during the reign of King Smbat II (977–89). In 992 the Armenian Catholicosate moved its seat to Ani. In the 10th century the population was perhaps 50,000–100,000.[21] By the start of the eleventh century the population of Ani was well over 100,000,[بحاجة لمصدر] and its renown was such that it was known as the "city of forty gates" and the "city of a thousand and one churches." Ani also became the site of the royal mausoleum of Bagratuni kings.[22]

Ani attained the peak of its power during the long reign of King Gagik I (989–1020). After his death his two sons quarreled over the succession. The eldest son, Hovhannes-Smbat (1020–41), gained control of Ani while his younger brother, Ashot IV (1020–40), controlled other parts of the Bagratuni kingdom. Hovhannes-Smbat, fearing that the Byzantine Empire would attack his now-weakened kingdom, made the Byzantine Emperor Basil II his heir.[23] When Hovhannes-Smbat died in 1041, Emperor Michael IV the Paphlagonian, claimed sovereignty over Ani. The new king of Ani, Gagik II (1042–45), opposed this and several Byzantine armies sent to capture Ani were repulsed. However, in 1046 Ani surrendered to the Byzantines,[7] after Gagik was invited to Constantinople and detained there, and at the instigation of pro-Byzantine elements among its population. A Byzantine governor was installed in the city.[15]

مركز ثقافي واقتصادي

Ani did not lie along any previously important trade routes, but because of its size, power, and wealth it became an important trading hub. Its primary trading partners were the Byzantine Empire, the Persian Empire, the Arabs, as well as smaller nations in southern Russia and Central Asia.[15]

الانحدار والتخلي التدريجي

In 1064, a large Seljuk army under Alp Arslan attacked Ani; after a siege of 25 days, they captured the city and slaughtered its population.[6] An account of the sack and massacres in Ani is given by the Arab historian Sibt ibn al-Jawzi, who quotes an eyewitness saying:

Putting the Persian sword to work, they spared no one... One could see there the grief and calamity of every age of human kind. For children were ravished from the embraces of their mothers and mercilessly hurled against rocks, while the mothers drenched them with tears and blood... The city became filled from one end to the other with bodies of the slain and [the bodies of the slain] became a road. [...] The army entered the city, massacred its inhabitants, pillaged and burned it, leaving it in ruins and taking prisoner all those who remained alive...The dead bodies were so many that they blocked the streets; one could not go anywhere without stepping over them. And the number of prisoners was not less than 50,000 souls. I was determined to enter city and see the destruction with my own eyes. I tried to find a street in which I would not have to walk over the corpses; but that was impossible.[24]

In 1072, the Seljuks sold Ani to the Shaddadids, a Muslim Kurdish dynasty.[6] The Shaddadids generally pursued a conciliatory policy towards the city’s overwhelmingly Armenian and Christian population and actually married several members of the Bagratid nobility. Whenever the Shaddadid governance became too intolerant, however, the population would appeal to the Christian Kingdom of Georgia for help. The Georgians captured Ani five times between 1124 and 1209:[7] in 1124, 1161, 1174, 1199, and 1209.[25] The first three times, it was recaptured by the Shaddadids. In the year 1199, Georgia's Queen Tamar captured Ani and in 1201 gave the governorship of the city to the generals Zakare and Ivane.[26] Zakare was succeeded by his son Shanshe (Shahnshah). Zakare's new dynasty — the Zakarids — considered themselves to be the successors to the Bagratids. Prosperity quickly returned to Ani; its defences were strengthened and many new churches were constructed. The Mongols unsuccessfully besieged Ani in 1226, but in 1236 they captured and sacked the city, massacring large numbers of its population. Under the Mongols the Zakarids continued to rule Ani, as the vassals of the Georgian monarch.[27]

By the 14th century, the city was ruled by a succession of local Turkish dynasties, including the Jalayrids and the Kara Koyunlu (Black Sheep clan) who made Ani their capital. It was ruined by an earthquake in 1319.[6][7] Tamerlane captured Ani in the 1380s. On his death the Kara Koyunlu regained control but transferred their capital to Yerevan. In 1441 the Armenian Catholicosate did the same. The Persian Safavids then ruled Ani until it became part of the Turkish Ottoman Empire in 1579. A small town remained within its walls at least until the middle of the seventeenth century, but the site was entirely abandoned by 1735 when the last monks left the monastery in the Virgin's Fortress or Kizkale.

العصر الحديث

—James Bryce, 1876[28]

In the first half of the 19th century, European travelers discovered Ani for the outside world, publishing their descriptions in academic journals and travel accounts. The private buildings were little more than heaps of stones but grand public buildings and the city's double wall were preserved and reckoned to present "many points of great architectural beauty".[6] Ohannes Kurkdjian produced stereoscopic image of Ani in the 2nd half of the 19th century.

In 1878, the Ottoman Empire's Kars region—including Ani—was incorporated into the Russian Empire's Transcaucasian region.[7] In 1892 the first archaeological excavations were conducted at Ani, sponsored by the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences and supervised by the Georgian archaeologist and orientalist Nicholas Marr (1864–1934). Marr's excavations at Ani resumed in 1904 and continued yearly until 1917. Large sectors of the city were professionally excavated, numerous buildings were uncovered and measured, the finds were studied and published in academic journals, guidebooks for the monuments and the museum were written, and the whole site was surveyed for the first time.[29] Emergency repairs were also undertaken on those buildings that were most at risk of collapse. A museum was established to house the tens of thousands of items found during the excavations. This museum was housed in two buildings: the Minuchihr mosque, and a purpose-built stone building.[30] Armenians from neighboring villages and towns also began to visit the city on a regular basis,[31] and there was even talk by Marr's team of building a school for educating the local Armenian children, building parks, and planting trees to beautify the site.[32]

In 1918, during the latter stages of World War I, the armies of the Ottoman Empire were fighting their way across the territory of the newly declared Republic of Armenia, capturing Kars in April 1918. At Ani, attempts were made to evacuate the artifacts contained in the museum as Turkish soldiers were approaching the site. About 6000 of the most portable items were removed by archaeologist Ashkharbek Kalantar, a participant of Marr's excavation campaigns. At the behest of Joseph Orbeli, the saved items were consolidated into a museum collection; they are currently part of the collection of Yerevan's State Museum of Armenian History.[33] Everything that was left behind was later looted or destroyed.[34] Turkey's surrender at the end of World War I led to the restoration of Ani to Armenian control, but a resumed offensive against the Armenian Republic in 1920 resulted in Turkey's recapture of Ani. In 1921 the signing of the Treaty of Kars formalized the incorporation of the territory containing Ani into the Republic of Turkey.[35]

In May 1921, the government minister Rıza Nur ordered the commander of the Eastern Front, Kazım Karabekir, for the monuments of Ani to "be wiped off the face of the earth."[36] Karabekir records in his memoirs that he has vigorously rejected this command and it has never been carried out.[37] Some destruction did take place, including most of Marr's excavations and building repairs.[38]

الحالة الحالية

Today, according to Lonely Planet and Frommer's travel guides to Turkey:

Official permission to visit Ani is no longer needed. Just go to Ani and buy a ticket. If you don't have your own car, haggle with a taxi or minibus driver in Kars for the round-trip to Ani, perhaps sharing the cost with other travelers. If you have trouble, the Tourist Office may help. Plan to spend at least a half-day at Ani. It's not a bad idea to bring a picnic lunch and a water bottle.[39]

According to The Economist, Armenians have "accused the Turks of neglecting the place in a spirit of chauvinism. The Turks retort that Ani's remains have been shaken by blasts from a quarry on the Armenian side of the border.[13]

Another commentator said: Ani is now a ghost city, uninhabited for over three centuries and marooned inside a Turkish military zone on Turkey's decaying closed border with the modern Republic of Armenia. Ani's recent history has been one of continuous and always increasing destruction. Neglect, earthquakes, cultural cleansing, vandalism, quarrying, amateurish restorations and excavations – all these and more have taken a heavy toll on Ani's monuments.[12]

In the estimation of the Landmarks Foundation (a non-profit organization established for the protection of sacred sites) this ancient city "needs to be protected regardless of whose jurisdiction it falls under. Earthquakes in 1319, 1832, and 1988, Army Target practice and general neglect all have had devastating effects on the architecture of the city. The city of Ani is a sacred place which needs ongoing protection.[40]"

Turkey's authorities now say they will do their best to conserve and develop the site and the culture ministry has listed Ani among the sites it is keenest to conserve. In the words of Mehmet Ufuk Erden, the local governor: "By restoring Ani, we'll make a contribution to humanity...We will start with one church and one mosque, and over time we will include every single monument."[13]

In an October 2010 report titled Saving Our Vanishing Heritage, Global Heritage Fund identified Ani as one of 12 worldwide sites most "On the Verge" of irreparable loss and destruction, citing insufficient management and looting as primary causes.[41][42]

The World Monuments Fund (WMF) placed Ani on its 1996, 1998, and 2000 Watch Lists of 100 Most Endangered Sites. In May 2011, WMF announced it was beginning conservation work on the cathedral and Church of the Holy Redeemer in partnership with the Turkish Ministry of Culture.[43]

In March 2015, it was reported that Turkey will nominate Ani to be listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2016.[44] The archaeological site of Ani was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site on July 15, 2016.[45] According to art historian Heghnar Zeitlian Watenpaugh the addition "would secure significant benefits in protection, research expertise, and funding."[46]

الآثار في آني

All the structures at Ani are constructed using the local volcanic basalt, a sort of tufa stone. It is easily carved and comes in a variety of vibrant colors, from creamy yellow, to rose-red, to jet black. The most important surviving monuments are as follows.

الكاتدرائية

Also known as Surp Asdvadzadzin (the Church of the Holy Mother of God), its construction was started in the year 989, under King Smbat II. Work was halted after his death, and was only finished in 1001 (or in 1010 under another reading of its building inscription). The design of the cathedral was the work of Trdat, the most celebrated architect of medieval Armenia. The cathedral is a domed basilica (the dome collapsed in 1319). The interior contains several progressive features (such as the use of pointed arches and clustered piers) that give to it the appearance of Gothic architecture (a style which the Ani cathedral predates by several centuries).[47]

كنيسة سورب ستيفانوس

There is no inscription giving the date of its construction, but an edict in Georgian is dated 1218. The church was referred to as "Georgian". During this period "Georgian" did not simply mean an ethnic Georgian, it had a denominational meaning and would have designated all those in Ani who professed the Chalcedonian faith, mostly Armenians. Although the Georgian Church controlled this church, its congregation would have mostly been Armenians.[48]

كنيسة القديس گريگوريوس تيگران

This church, finished in 1215, is the best-preserved monument at Ani. It was built during the rule of the Zakarids and was commissioned by the wealthy Armenian merchant Tigran Honents.[49] Its plan is of a type called a domed hall. In front of its entrance are the ruins of a narthex and a small chapel that are from a slightly later period. The exterior of the church is spectacularly decorated. Ornate stone carvings of real and imaginary animals fill the spandrels between blind arcade that runs around all four sides of the church. The interior contains an important and unique series of frescoes cycles that depict two main themes. In the eastern third of the church is depicted the Life of Saint Gregory the Illuminator, in the middle third of the church is depicted the Life of Christ. Such extensive fresco cycles are rare features in Armenian architecture – it is believed that these ones were executed by Georgian artists, and the cycle also includes scenes from the life of St. Nino, who converted the Georgians to Christianity. In the narthex and its chapel survive fragmentary frescoes that are more Byzantine in style.[50]

كنيسة الفادي المقدس

This church was completed shortly after the year 1035. It had a unique design: 19-sided externally, 8-apsed internally, with a huge central dome set upon a tall drum. It was built by Prince Ablgharib Pahlavid to house a fragment of the True Cross. The church was largely intact until 1955, when the entire eastern half collapsed during a storm.[51]

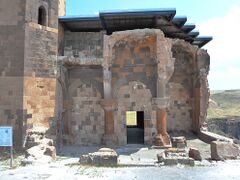

كنيسة القديس گريگوريوس الأبوگامريون

This small building probably dates from the late 10th century. It was built as a private chapel for the Pahlavuni family. Their mausoleum, built in 1040 and now reduced to its foundations, was constructed against the northern side of the church. The church has a centralised plan, with a dome over a drum, and the interior has six exedera.[52]

كنيسة الملك جاجيك للقديس گريگوريوس

Also known as the Gagikashen, this church was constructed between the years 1001 and 1005 and intended to be a recreation of the celebrated cathedral of Zvartnots at Vagharshapat. Nikolai Marr uncovered the foundations of this remarkable building in 1905 and 1906. Before that, all that was visible on the site was a huge earthen mound. The designer of the church was the architect Trdat. The church is known to have collapsed a relatively short time after its construction and houses were later constructed on top of its ruins. Trdat's design closely follows that of Zvartnotz in its size and in its plan (a quatrefoil core surrounded by a circular ambulatory).[53]

كنيسة الرسل القديسين

The date of its construction is not known, but the earliest dated inscription on its walls is from 1031. It was founded by the Pahlavuni family and was used by the archbishops of Ani (many of whom belonged to that dynasty). It has a plan of a type called an inscribed quatrefoil with corner chambers. Only fragments remain of the church, but a narthex with spectacular stonework, built against the south side of the church, is still partially intact. It dates from the early 13th century. A number of other halls, chapels, and shrines once surrounded this church: Nicholas Marr excavated their foundations in 1909, but they are now mostly destroyed.[54]

مسجد مانوشهر

The mosque is named after its presumed founder, Manuchihr, the first member of the Shaddadid dynasty that ruled Ani after 1072. The oldest surviving part of the mosque is its still intact minaret. It has the Arabic word Bismillah ("In the name of God") in Kufic lettering high on its northern face. The prayer hall, half of which survives, dates from a later period (the 12th or 13th century). In 1906 the mosque was partially repaired in order for it to house a public museum containing objects found during Nicholas Marr's excavations.[55]

القلعة

At the southern end of Ani is a flat-topped hill once known as Midjnaberd (the Inner Fortress). It has its own defensive walls that date back to the period when the Kamsarakan dynasty ruled Ani (7th century AD). Nicholas Marr excavated the citadel hill in 1908 and 1909. He uncovered the extensive ruins of the palace of the Bagratid kings of Ani that occupied the highest part of the hill. Also inside the citadel are the visible ruins of three churches and several unidentified buildings. One of the churches, the "church of the palace" is the oldest surviving church in Ani, dating from the 6th or 7th century. Marr undertook emergency repairs to this church, but most of it has now collapsed – probably during an earthquake in 1966.[56]

أسوار المدينة

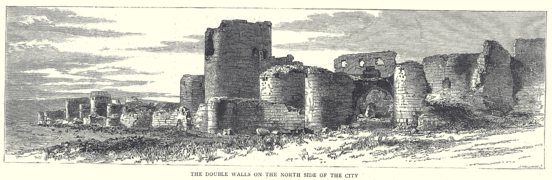

A line of walls that encircled the entire city defended Ani. The most powerful defences were along the northern side of the city, the only part of the site not protected by rivers or ravines. Here the city was protected by a double line of walls, the much taller inner wall studded by numerous large and closely spaced semicircular towers. Contemporary chroniclers wrote that King Smbat (977–989) built these walls. Later rulers strengthened Smbat's walls by making them substantially higher and thicker, and by adding more towers. Armenian inscriptions from the 12th and 13th century show that private individuals paid for some of these newer towers. The northern walls had three gateways, known as the Lion Gate, the Kars Gate, and the Dvin Gate (also known as the Chequer-Board Gate because of a panel of red and black stone squares over its entrance).[57]

آثار أخرى

There are many other minor monuments at Ani. These include a convent known as the Virgins' chapel; a church used by Chalcedonian Armenians; the remains of a single-arched bridge over the Arpa river; the ruins of numerous oil-presses and several bath houses; the remains of a second mosque with a collapsed minaret; a palace that probably dates from the 13th century; the foundations of several other palaces and smaller residences; the recently excavated remains of several streets lined with shops; etc.

قرية الكهف

Directly outside of Ani, there was a settlement-zone carved into the cliffs. It may have served as "urban sprawl" when Ani grew too large for its city walls. Today, goats and sheep take advantage of the caves' cool interiors. One highlight of this part of Ani is a cave church with frescos on its surviving walls and ceiling.

معرض الصور

Church of St. Gregory of the Abughamrents; in the background is the citadel.

بانوراما

في الثقافة

Ani is one of the most popular female given names in Armenia.[58]

Songs and poems have been written about Ani and its past glory. "Tesnem Anin u nor mernem" (Տեսնեմ Անին ու նոր մեռնեմ, Let me see Ani before I die) is a famous poem by Hovhannes Shiraz. It was turned into a song by Turkish-Armenian composer Cenk Taşkan.[59][60] Ara Gevorgyan's 1999 album of folk instrumental songs is titled Ani.[61]

معرض الصور

مرئيات

| متروبوليس من القرون الوسطى.. |

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- Notes

- اقتباسات

- ^ Watenpaugh 2014, p. 531.

- ^ "Büyük Katedral (Fethiye Cami) - Kars". kulturportali.gov.tr (in التركية).

Adres: Ocaklı Köyü, Ani Antik Kenti

- ^ Hasratyan, Murad (2011). "Անիի ճարտարապետությունը [Architecture of Ani]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (3): 8.

Դարպասի վերևի պատին Անի քաղաքի զինանշանն է՝ հովազի բարձրաքանդակով:

- ^ Անի. encyclopedia.am (in الأرمنية). Armenian Encyclopedia.

Անիի զինանշանը` վազող հովազը

- ^ Garsoïan, Nina G.; Taylor, Alice (1991), "Ani", in Kazhdan, Alexander, The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195046526

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 72

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 2 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 47.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 2 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 47. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "ანისი [anisi]" (in Georgian). National Parliamentary Library of Georgia. Retrieved نوفمبر 4, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Ziflioğlu, Vercihan (أبريل 14, 2009). "Building a dialogue atop old ruins of Ani". Hürriyet. Archived from the original on يوليو 12, 2016.

The Turkish government's practice of calling the town "Anı," rather than Ani, in order to give it a more Turkish character...

- ^ (أرمنية) Hakobyan, Tadevos. (1980). Անիի Պատմություն, Հնագույն Ժամանակներից մինչև 1045 թ. [The History of Ani, from Ancient Times Until 1045], vol. I. Yerevan: Yerevan State University Press, pp. 214–217.

- ^ Not to confuse with the Binbirkilise/'1001 churches' near Karaman in modern Turkey'

- ^ أ ب Sim, Steven. "VirtualANI – Dedicated to the Deserted Medieval Armenian City of Ani". VirtualANI. Archived from the original on يناير 20, 2007. Retrieved يناير 22, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب ت "Ani, a Disputed City Haunted by History". The Economist. يونيو 15, 2006.

- ^ Joel Mokyr. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History. — Oxford University Press, 2003. — P. 157 "The struggle against Persian, Byzantine, and Arab political and economic domination, however, led to the restoration of the Armenian Kingdom (885-1045). Crafts and agricultural prospered. Its capital, Ani, famous for Armenian classical architecture, became one of the biggest cities in the world."

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Ghafadaryan, Karo (1974). "Անի [Ani]". Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia Volume I (in الأرمنية). Armenian Academy of Sciences. p. 407–412.

- ^ أ ب ت Panossian 2006, p. 60.

- ^ Mutafian, Claude. "Ani after Ani: Eleventh to Seventeenth Centuries", in Armenian Kars and Ani, ed. Richard G. Hovannisian, Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2011, pp. 163-64.

- ^ Vanadzin, Katie (يناير 29, 2015). "Recent Publication Highlights Complexities of Uncovering the History of the Medieval City of Ani". Armenian Weekly.

As Watenpaugh explains, "Ani is so symbolic, so central for Armenians, as a religious site, as a cultural site, as a national heritage symbol, a symbol of nationhood."

- ^ Whittow, Mark (1996). The Making of Byzantium, 600–1025. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 213–214. ISBN 978-0-520-20497-3.

- ^ Garsoian, Nina. "The Arab Invasions and the Rise of the Bagratuni (649–684)" in The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times, Volume I, The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century, ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. New York: St Martin's Press, 1997, p. 146. ISBN 978-0-312-10169-5

- ^ Redgate, Anne Elizabeth. The Armenians. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1998, p. 210.

- ^ Manuk-Khaloyan, Armen, "In the Cemetery of their Ancestors: The Royal Burial Tombs of the Bagratuni Kings of Greater Armenia (890-1073/79)", Revue des Études Arméniennes 35 (2013): 147-155.

- ^ Whittow. Making of Byzantium, p. 383.

- ^ Quoted in Norwich, John Julius (1991). Byzantium: The Apogee. New York: Viking. pp. 342–343. ISBN 978-0-394-53779-5.

- ^ Georgian National Academy of Sciences, Kartlis Tskhovreba (History of Georgia), Artanuji pub. Tbilisi 2014

- ^ Lordkipanidze, Mariam (1987). Georgia in the XI-XII Centuries. Tbilisi: Genatleba. p. 150.

- ^ Eastern Turkey: An Architectural and Archaeological Survey, 1. T. A. Sinclair

- ^ Bryce, James (1878). Transcaucasia and Ararat: Being Notes of a Vacation Tour in Autumn of 1876 (3rd ed.). London: Macmillan and Co. p. 301.

- ^ Kalantar, Ashkharbek, The Mediaeval Inscriptions of Vanstan, Armenia, Civilisations du Proche-Orient: Series 2 – Philologie – CDPOP 2, Vol. 2, Recherches et Publications, Neuchâtel, Paris, 1999; ISBN 978-2-940032-11-2

- ^ Marr, Nicolas (2001). Ani – Rêve d'Arménie. Anagramme Editions. ISBN 978-2-914571-00-5.

- ^ Manuk-Khaloyan, Armen. "The God-Borne Days of Ani: A Revealing Look at the Former Medieval Armenian Capital of Armenia at the Turn of the 20th Century." Armenian Weekly. November 29, 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ Hakobyan, Tadevos (1982). Անիի Պատմություն, 1045 թ. մինչև անկումն ու ամայացումը [The History of Ani, from 1045 Until its Collapse and Abandonment], vol. 2 (in الأرمنية). Yerevan: Yerevan State University Press. pp. 368–386.

- ^ Kalantar, Ashkharbek (1994). Armenia from the Stone Age to the Middle Ages. Recherches et Publications. ISBN 978-2-940032-01-3.

- ^ Marr, Nikolai Y. "Ani, La Ville Arménniene en Ruines", Revue des Études Arméniennes. vol. 1 (original series), 1921.

- ^ (أرمنية) Zohrabyan, Edik A. (1979). Սովետական Ռուսաստանը և հայ-թուրքական հարաբերությունները, 1920–1922 թթ. [Soviet Russia and Armenian-Turkish Relations, 1920–1922]. Yerevan: Yerevan State University Press, pp. 277–80.

- ^ Dadrian, Vahakn N. (1986). "The Role of Turkish Physicians in the World War I Genocide of Ottoman Armenians". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. 1 (2): 192.

- ^ Karabekir, Kazım (1960). Istiklal Harbimiz [Our War of Independence] (in التركية). Istanbul: Türkiye Yayınevi. pp. 960–970.

- ^ Sim, Steven. "The City of Ani: Recent History". VirtualANI. Archived from the original on يناير 26, 2007. Retrieved يناير 26, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Brosnahan, Tom. "Ancient Armenian City of Ani". Turkey Travel Planner. Archived from the original on يناير 1, 2007. Retrieved يناير 22, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "SACRED SITE". Ani, Turkey. Landmarks Foundation. Archived from the original on مايو 26, 2008. Retrieved يناير 22, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Global Heritage in the Peril: Sites on the Verge". Global Heritage Fund. أكتوبر 2010. Archived from the original on أبريل 22, 2011. Retrieved يونيو 3, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ John Roach (أكتوبر 23, 2010). "Pictures: 12 Ancient Landmarks on Verge of Vanishing". National Geographic. Archived from the original on يونيو 15, 2011. Retrieved يونيو 3, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism and World Monuments Fund Collaborate on Historic Conservation Project in Eastern Turkey" (PDF). World Monuments Fund. مايو 2011. Retrieved نوفمبر 17, 2011.

- ^ "Work ongoing to put Ani on UNESCO heritage list". Hürriyet Daily News. مارس 2, 2015.

- ^ "Five sites inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage List". UNESCOPRESS. UNESCO. يوليو 15, 2016.

- ^ "Ani Included on UNESCO World Heritage List". Armenian Weekly. يوليو 15, 2016.

- ^ Sim, Steven. "The cathedral of Ani". VirtualANI. Archived from the original on يناير 20, 2007. Retrieved يناير 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sim, Steven. "THE GEORGIAN CHURCH". VirtualANI. Retrieved فبراير 15, 2012.

- ^ Coureas, Nicholas; Edbury, Peter; Walsh, Michael J.K. (2012). Medieval and Renaissance Famagusta : Studies in Architecture, Art and History. Farnham: Ashgate. p. 139. ISBN 1409435571.

- ^ Sim, Steven. "The church of St. Gregory of Tigran Honents". VirtualANI. Archived from the original on مايو 22, 2007. Retrieved يناير 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sim, Steven. "The church of the Redeemer". VirtualANI. Archived from the original on يناير 20, 2007. Retrieved يناير 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sim, Steven. "The church of St. Gregory of the Abughamir family". VirtualANI. Archived from the original on مايو 24, 2007. Retrieved يناير 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sim, Steven. "King Gagik's church of St. Gregory". VirtualANI. Archived from the original on سبتمبر 26, 2007. Retrieved يناير 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sim, Steven. "Church of the Holy Apostles". VirtualANI. Archived from the original on فبراير 16, 2007. Retrieved يناير 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sim, Steven. "The mosque of Minuchihr". VirtualANI. Archived from the original on يناير 20, 2007. Retrieved يناير 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sim, Steven. "The citadel of Ani". VirtualANI. Archived from the original on يونيو 3, 2007. Retrieved يناير 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sim, Steven. "The city walls of Ani". VirtualANI. Archived from the original on يوليو 17, 2007. Retrieved يناير 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Which are most common Armenian names?". News.am. أغسطس 27, 2012. Retrieved أغسطس 10, 2013.

- ^ "Forums / Հայկական Երգերի Շտեմարան / Հայաստան - Կրթական Տեխնոլոգիաների Ազգային Կենտրոն". Ktak.am. Archived from the original on أكتوبر 29, 2013. Retrieved أغسطس 15, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "'Ani', A Poem By Hovhannes Shiraz". Yerevan2012.org. فبراير 16, 2012. Retrieved أغسطس 15, 2013.

- ^ "Ani". Ara Gevorgyan Website. Retrieved أغسطس 10, 2013.

فهرس

- عام

- Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231139267.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- محددة

- Watenpaugh, Heghnar Zeitlian (2014). "Preserving the Medieval City of Ani: Cultural Heritage between Contest and Reconciliation". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 73 (4): 528–555. doi:10.1525/jsah.2014.73.4.528. JSTOR 10.1525/jsah.2014.73.4.528.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

للاستزادة

- Brosset, Marie-Félicité (1860–1861), Les Ruines d'Ani, Capital de l'Arménie sous les Rois Bagratides, aux Xe et XIe S, Histoire et Description, Ire Partie: Description, avec un Atlas de 24 Planches Lithographiées and IIe Partie: Histoire, avec un Atlas de 21 Planches Lithographiées, St Petersburg: Imperial Science Academy. (بالفرنسية)

- Cowe, S. Peter (2001). Ani: World Architectural Heritage of a Medieval Armenian Capital. Sterling, Virginia: Peeters.

- Hakobyan, Tadevos (1980–1982), 'Անիի Պատմություն, Հնագույն Ժամանակներից մինչև 1045 թ. [The History of Ani, from Ancient Times until 1045] and 1045 թ. մինչև անկումն ու ամայացումը [from 1045 until its Collapse and Abandonment]', Yerevan: Yerevan State University Press (أرمنية)

- Kevorkian, Raymond (2001). Ani – Capitale de l'Arménie en l'An Mil (in الفرنسية).

- Lynch, H.F.B. (1901). Armenia, Travels and Studies. London: Longmans. ISBN 1-4021-8950-8.

- Marr, Nicolas Yacovlevich (2001). Ani – Rêve d'Arménie (in الفرنسية). Paris: Anagramme Editions.

- Minorsky, Vladimir (1953). Studies in Caucasian History. ISBN 0-521-05735-3.

- Paolo, Cuneo (1984). Documents of Armenian Architecture, Vol. 12: Ani.

- Kalantar, Ashkharbek (1994). Armenia from the Stone Age to the Middle Ages.

- Sinclair, Thomas Allen (1987). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural and Archeological Survey, Volume 1. London: Pindar Press.

وصلات خارجية

| Find more about آني (مدينة) at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| Media from Commons | |

| Travel guide from Wikivoyage | |

- 360 Degree Virtual Tour Ani Armenian Cathedral – 360 Degree Virtual Tour Ani Armenian Cathedral

- 360 Degree Virtual Tour Ani Armenian Cathedral – 360 Degree Virtual Tour Ani Armenian Cathedral

- Virtual Ani – has clickable maps, extensive history and photos

- Photos of Ani

- World Monuments Fund/Turkish Ministry of Culture Ani Cathedral conservation project

- World Monuments Fund/Turkish Ministry of Culture Church of the Holy Savior/Redeemer conservation project

- 400+ pictures of Ani

- "The Ancient Ghost City of Ani". The Atlantic. يناير 24, 2014. - a gallery of 27 photos of Ani

- "The empire the world forgot". BBC. مارس 15, 2016.

]]

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 التركية-language sources (tr)

- CS1 uses الأرمنية-language script (hy)

- CS1 الأرمنية-language sources (hy)

- Wikipedia articles incorporating a citation from EB9

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Use mdy dates from August 2011

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing أرمنية-language text

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing جورجية-language text

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from June 2016

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2013

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2014

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- مواقع التراث العالمي في تركيا

- Bagratid Armenia

- Archaeological sites in Eastern Anatolia

- أماكن مأهولة سابقاً في تركيا

- Ruined churches in Turkey

- Former capitals of Armenia

- Populated places of the Byzantine Empire

- Buildings and structures in Kars Province

- World Heritage Sites in Turkey