اللغة البلغارية

| البلغارية | |

|---|---|

| български bălgarski | |

| |

| موطنها | بلغاريا، صربيا، شمال مقدونيا، اليونان، تركيا, Ukraine, مولدوڤا, رومانيا, روسيا |

| المنطقة | جنوب شرق أوروپا |

| العرق | البلغار |

الناطقون الأصليون | 8[1]–9[2][3][4][5] مليون (2011) |

| اللهجات | |

| الوضع الرسمي | |

لغة رسمية في | |

لغة أقلية معترف بها في | |

| ينظمها | Institute for Bulgarian Language at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences |

| أكواد اللغات | |

| ISO 639-2 | bul |

| ISO 639-2 | bul |

| ISO 639-3 | bul |

| Glottolog | bulg1262 |

| Linguasphere | 53-AAA-hb < 53-AAA-h |

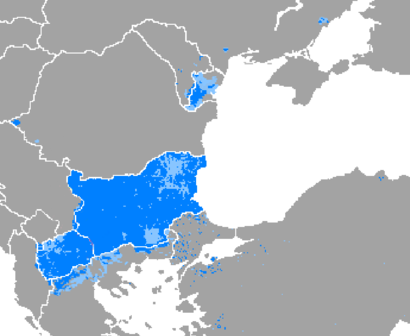

The Bulgarian-speaking world: regions where Bulgarian is the language of the majority regions where Bulgarian is the language of a significant minority | |

اللغة البلغارية ( /bʌlˈɡɛəriən/, /bʊlˈʔ/ bu(u)l-GAIR-ee-ən; بالبلغارية: български, تـُنطـَق [ˈbɤɫɡɐrski] (![]() استمع)) هي لغة سلاڤية جنوبية تُستَخدَم في جنوب شرق أوروپا، أساساً في بلغاريا. وهي لغة البلغار.

استمع)) هي لغة سلاڤية جنوبية تُستَخدَم في جنوب شرق أوروپا، أساساً في بلغاريا. وهي لغة البلغار.

Along with the closely related Macedonian language (collectively forming the East South Slavic languages), it is a member of the Balkan sprachbund. The two languages have several characteristics that set them apart from all other Slavic languages: changes include the elimination of case declension, the development of a suffixed definite article and the lack of a verb infinitive, but it retains and has further developed the Proto-Slavic verb system. One such major development is the innovation of evidential verb forms to encode for the source of information: witnessed, inferred, or reported.

It is the official language of Bulgaria, and since 2007 has been among the official languages of the European Union.[8][9] It is also spoken by minorities in several other countries.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ

One can divide the development of the Bulgarian language into several periods.

- The Prehistoric period covers the time between the Slavonic migration to the eastern Balkans (ح. 7th century CE) and the mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius to Great Moravia in the 860s.

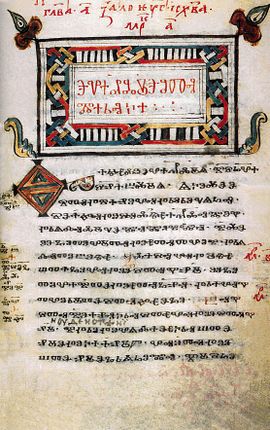

- Old Bulgarian (9th to 11th centuries, also referred to as "Old Church Slavonic") – a literary norm of the early southern dialect of the Common Slavic language from which Bulgarian evolved. Saints Cyril and Methodius and their disciples used this norm when translating the Bible and other liturgical literature from Greek into Slavic.

- Middle Bulgarian (12th to 15th centuries) – a literary norm that evolved from the earlier Old Bulgarian, after major innovations occurred. A language of rich literary activity, it served as the official administration language of the Second Bulgarian Empire.

- Modern Bulgarian dates from the 16th century onwards, undergoing general grammar and syntax changes in the 18th and 19th centuries. The present-day written Bulgarian language was standardized on the basis of the 19th-century Bulgarian vernacular. The historical development of the Bulgarian language can be described as a transition from a highly synthetic language (Old Bulgarian) to a typical analytic language (Modern Bulgarian) with Middle Bulgarian as a midpoint in this transition.

Bulgarian was the first Slavic language attested in writing.[10] As Slavic linguistic unity lasted into late antiquity, the oldest manuscripts initially referred to this language as ѧзꙑкъ словѣньскъ, "the Slavic language". In the Middle Bulgarian period this name was gradually replaced by the name ѧзꙑкъ блъгарьскъ, the "Bulgarian language". In some cases, this name was used not only with regard to the contemporary Middle Bulgarian language of the copyist but also to the period of Old Bulgarian. A most notable example of anachronism is the Service of Saint Cyril from Skopje (Скопски миней), a 13th-century Middle Bulgarian manuscript from northern Macedonia according to which St. Cyril preached with "Bulgarian" books among the Moravian Slavs. The first mention of the language as the "Bulgarian language" instead of the "Slavonic language" comes in the work of the Greek clergy of the Archbishopric of Ohrid in the 11th century, for example in the Greek hagiography of Clement of Ohrid by Theophylact of Ohrid (late 11th century).

During the Middle Bulgarian period, the language underwent dramatic changes, losing the Slavonic case system, but preserving the rich verb system (while the development was exactly the opposite in other Slavic languages) and developing a definite article. It was influenced by its non-Slavic neighbors in the Balkan language area (mostly grammatically) and later also by Turkish, which was the official language of the Ottoman Empire, in the form of the Ottoman Turkish language, mostly lexically. As a national revival occurred toward the end of the period of Ottoman rule (mostly during the 19th century), a modern Bulgarian literary language gradually emerged that drew heavily on Church Slavonic/Old Bulgarian (and to some extent on literary Russian, which had preserved many lexical items from Church Slavonic) and later reduced the number of Turkish and other Balkan loans. Today one difference between Bulgarian dialects in the country and literary spoken Bulgarian is the significant presence of Old Bulgarian words and even word forms in the latter. Russian loans are distinguished from Old Bulgarian ones on the basis of the presence of specifically Russian phonetic changes, as in оборот (turnover, rev), непонятен (incomprehensible), ядро (nucleus) and others. Many other loans from French, English and the classical languages have subsequently entered the language as well.

Modern Bulgarian was based essentially on the Eastern dialects of the language, but its pronunciation is in many respects a compromise between East and West Bulgarian (see especially the phonetic sections below). Following the efforts of some figures of the National awakening of Bulgaria (most notably Neofit Rilski and Ivan Bogorov),[11] there had been many attempts to codify a standard Bulgarian language; however, there was much argument surrounding the choice of norms. Between 1835 and 1878 more than 25 proposals were put forward and "linguistic chaos" ensued.[12] Eventually the eastern dialects prevailed,[13] and in 1899 the Bulgarian Ministry of Education officially codified[12] a standard Bulgarian language based on the Drinov-Ivanchev orthography.[13]

التوزع الجغرافي

Bulgarian is the official language of Bulgaria,[14] where it is used in all spheres of public life. As of 2011, it is spoken as a first language by about 6 million people in the country, or about four out of every five Bulgarian citizens.[15]

There is also a significant Bulgarian diaspora abroad. One of the main historically established communities are the Bessarabian Bulgarians, whose settlement in the Bessarabia region of nowadays Moldavia and Ukraine dates mostly to the early 19th century. There were 134٬000 Bulgarian speakers in Ukraine at the 2001 census,[16] 41٬800 in Moldova as of the 2014 census (of which 15٬300 were habitual users of the language),[17] and presumably a significant proportion of the 13,200 ethnic Bulgarians residing in neighbouring Transnistria in 2016.[18]

Another community abroad are the Banat Bulgarians, who migrated in the 17th century to the Banat region now split between Romania, Serbia and Hungary. They speak the Banat Bulgarian dialect, which has had its own written standard and a historically important literary tradition.

There are Bulgarian speakers in neighbouring countries as well. The regional dialects of Bulgarian and Macedonian form a dialect continuum, and there is no well-defined boundary where one language ends and the other begins. Within the limits of the Republic of North Macedonia a strong separate Macedonian identity has emerged since the Second World War, even though there still are a small number of citizens who identify their language as Bulgarian. Beyond the borders of North Macedonia, the situation is more fluid, and the pockets of speakers of the related regional dialects in Albania and in Greece variously identify their language as Macedonian or as Bulgarian. In Serbia, there were 13٬300 speakers as of 2011,[19] mainly concentrated in the so-called Western Outlands along the border with Bulgaria. Bulgarian is also spoken in Turkey: natively by Pomaks, and as a second language by many Bulgarian Turks who emigrated from Bulgaria, mostly during the "Big Excursion" of 1989.

The language is also represented among the diaspora in Western Europe and North America, which has been steadily growing since the 1990s. Countries with significant numbers of speakers include Germany, Spain, Italy, the United Kingdom (38٬500 speakers in England and Wales as of 2011),[20] France, the United States, and Canada (19٬100 in 2011).[21]

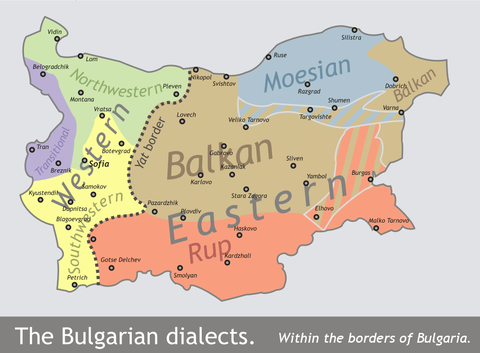

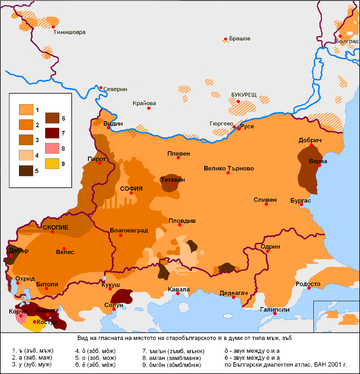

اللهجات

العلاقة بالمقدونية

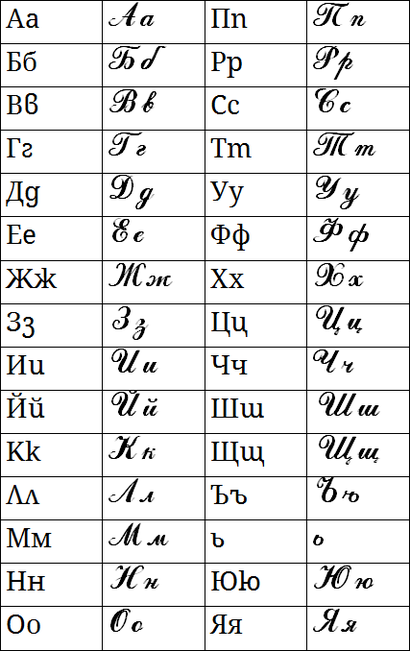

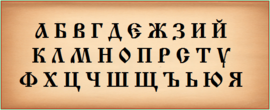

الأبجدية

في 886 م، قدّمت الامبراطورية البلغارية Glagolitic alphabet which was devised by the Saints Cyril and Methodius in the 850s. The Glagolitic alphabet was gradually superseded in later centuries by the Cyrillic script, developed around the Preslav Literary School, بلغاريا في القرن التاسع.

في الجدول التالي الحروف الأبجدية البلغارية:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ь ь | Ю ю | Я я |

معجم

Most of the vocabulary of modern Bulgarian consists of terms inherited from Proto-Slavic and local Bulgarian innovations and formations of those through the mediation of Old and Middle Bulgarian. The native terms in Bulgarian account for 70% to 80% of the lexicon.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

انظر أيضاً

- Abstand and ausbau languages

- Balkan sprachbund

- Banat Bulgarian language

- اسم بلغاري

- Orthodox Slavs

- Slavic language (Greece)

- Swadesh list of Slavic languages

- Torlakian dialect

- The BABEL Speech Corpus

ملاحظات

المراجع

- ^ "Bulgarian".

- ^ "Bulgarian language". The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. Columbia University Press.

- ^ Rehm, Georg; Uszkoreit, Hans (2012). "The Bulgarian Language in the European Information Society". The Bulgarian Language in the Digital Age. White Paper Series. Vol. 4. Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 50–57. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-30168-1_8. ISBN 978-3-642-30167-4.

- ^ Strazny, Philipp (2005). Encyclopedia of Linguistics: M-Z (1 ed.). Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 958. ISBN 978-1579583910.

- ^ Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. ISBN 9781593394929.

- ^ "Národnostní menšiny v České republice a jejich jazyky" [National Minorities in Czech Republic and Their Language] (PDF) (in Czech). Government of Czech Republic. p. 2.

Podle čl. 3 odst. 2 Statutu Rady je jejich počet 12 a jsou uživateli těchto menšinových jazyků: ..., srbština a ukrajinština

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Implementation of the Charter in Hungary". Database for the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Public Foundation for European Comparative Minority Research. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ EUR-Lex (12 December 2006). "Council Regulation (EC) No 1791/2006 of 20 November 2006". Official Journal of the European Union. Europa web portal. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- ^ "Languages in Europe – Official EU Languages". EUROPA web portal. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 12 October 2009.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةEB1911 - ^ Michal Kopeček. Discourses of collective identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770–1945): texts and commentaries, Volume 1 (Central European University Press, 2006), p. 248

- ^ أ ب Glanville Price. Encyclopedia of the languages of Europe (Wiley-Blackwell, 2000), p.45

- ^ أ ب Victor Roudometof. Collective memory, national identity, and ethnic conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian question (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002), p. 92

- ^ "Constitution of the Republic of Bulgaria" (in البلغارية). Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Национален Статистически Институт (2012). Преброяване на населението и жилищния фонд през 2011 година (in البلغارية). Vol. Том 1: Население. София. pp. 33–34, 190.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Of the 6.64 million people who answered the optional language question in the 2011 census, 5.66 million (or 85.2%) reported being native speakers of Bulgarian (this amounts to 76.8% of the total population of 7.36 million). - ^ "Table 19A050501 02. Distribution of the population of Ukraine's regions by native language (0,1)". Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "The Population of the Republic of Moldova at the Time of the Census was 2,998,235". 31 March 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2020. The full data is available in the linked spreadsheet titled "Characteristics - Population", sheets 8 and 9.

- ^ "Статистический ежегодник 2017 - Министерство экономического развития Приднестровской Молдавской Республики". mer.gospmr.org. Retrieved 16 October 2020. There is no data on the number of speakers.

- ^ (in sr)Etnokonfesionalni i jezički mozaik Srbije (Popis stanovništa, domaćinstava i stanova 2011. u Republici Srbiji). pp. 151–56. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://pod2.stat.gov.rs/ObjavljenePublikacije/Popis2011/Etnomozaik.pdf. - ^ "DC2210EWr - Main language by proficiency in English (regional)". Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "Census Profile". 8 February 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Кочев (Kochev), Иван (Ivan) (2001). Български диалектен атлас (Bulgarian dialect atlas) (in Bulgarian). София: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. ISBN 954-90344-1-0. OCLC 48368312.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Corbett, Professor Greville; Comrie, Professor Bernard (2003). The Slavonic Languages. Routledge. p. 239. ISBN 9781136861444.

The relative weight of inherited Proto-Slavonic material can be estimated from Nikolova (1987) – a study of a 100,000-word corpus of conversational Bulgarian. Of the 806 items occurring there more than ten times, approximately 50 per cent may be direct reflexes of Proto Slavonic forms, nearly 30 per cent are later Bulgarian formations and 17 per cent are foreign borrowings

- ^ Corbett, Professor Greville; Comrie, Professor Bernard (2003). The Slavonic Languages. Routledge. p. 240. ISBN 9781136861444.

ببليوگرافيا

- Pisani, Vittore (2012). Old Bulgarian Language. Sofia: Bukvitza. ISBN 978-9549285864.

- Comrie, Bernard; Corbett, Greville G. (1993). The Slavonic Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-04755-5.

- Klagstad Jr., Harold L. (1958), The Phonemic System of Colloquial Standard Bulgarian, American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages, pp. 42–54

- Ternes, Elmer; Vladimirova-Buhtz, Tatjana (1999), "Bulgarian", Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, Cambridge University Press, pp. 55–57, ISBN 978-0-521-63751-0

- Бояджиев и др. (1998) Граматика на съвременния български книжовен език. Том 1. Фонетика

- Жобов, Владимир (2004) Звуковете в българския език

- Кръстев, Боримир (1992) Граматика за всички

- Пашов, Петър (1999) Българска граматика

- Vladimir I. Georgiev, ed. (1971–2011), Български етимологичен речник, I-VII, Българска академия на науките

- Notes on the Grammar of the Bulgarian language - 1844 - Smyrna (now Izmir) - Elias Riggs

وصلات خارجية

| Find more about Bulgarian language at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| Definitions from Wiktionary | |

| Media from Commons | |

| Textbooks from Wikibooks | |

| Travel guide from Wikivoyage | |

تقارير لسانية

- Bulgarian at Omniglot

- Bulgarian Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh list appendix)

- Information about the linguistic classification of the Bulgarian language (from Glottolog)

- The linguistic features of the Bulgarian language (from WALS, The World Atlas of Language Structures Online)

- Information about the Bulgarian language from the PHOIBLE project.

- Locale Data Summary for the Bulgarian language from Unicode's CLDR

القواميس

- Eurodict — multilingual Bulgarian dictionaries

- Rechnik.info — online dictionary of the Bulgarian language

- Rechko — online dictionary of the Bulgarian language

- Bulgarian–English–Bulgarian Online dictionary from SA Dictionary

- Online Dual English–Bulgarian dictionary

- Bulgarian bilingual dictionaries

- English, Bulgarian bidirectional dictionary

الكورسات

قالب:Bulgarian language قالب:Bulgarian dialects قالب:Languages of Bulgaria

- CS1 البلغارية-language sources (bg)

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing بلغارية-language text

- Languages with ISO 639-2 code

- Languages with ISO 639-1 code

- Language articles without reference field

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using bar box without float left or float right

- Use British English from October 2012

- لغات تحليلية

- Bulgarian language

- Languages of Bulgaria

- Languages of Greece

- Languages of Romania

- Languages of Serbia

- Languages of North Macedonia

- Languages of Turkey

- Languages of Moldova

- Languages of Ukraine

- South Slavic languages

- Subject–verb–object languages

- لغات سلافية جنوبية

- لغات بلغاريا

- لغات مقدونيا