حركة قبوية

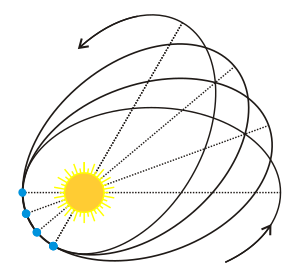

الحركة القبوية apsidal motion هى حركة خط القبوين لأحد المدارات الفلكية وفى النجوم الثنائية إذا كان أحد النجمين أو كلاهما ليس كرويا فإن الحركة القبوية تحدث نتيجة لقوة جاذبية جرم آخر.

The apsides are the orbital points closest (periapsis) and farthest (apoapsis) from its primary body. The apsidal precession is the first derivative of the argument of periapsis, one of the six main orbital elements of an orbit. Apsidal precession is considered positive when the orbit's axis rotates in the same direction as the orbital motion.

التاريخ

الحساب

A variety of factors can lead to periastron precession such as general relativity, stellar quadrupole moments, mutual star–planet tidal deformations, and perturbations from other planets.[1]

- ωtotal = ωGeneral Relativity + ωquadrupole + ωtide + ωperturbations

For Mercury, the perihelion precession rate due to general relativistic effects is 43″ (arcseconds) per century. By comparison, the precession due to perturbations from the other planets in the Solar System is 532″ per century, whereas the oblateness of the Sun (quadrupole moment) causes a negligible contribution of 0.025″ per century.[2][3]

مبرهنة نيوتن للمدارات الدوارة

النسبية العامة

An apsidal precession of the planet Mercury was noted by Urbain Le Verrier in the mid-19th century and accounted for by Einstein's general theory of relativity.

Einstein showed that for a planet, the major semi-axis of its orbit being α, the eccentricity of the orbit e and the period of revolution T, then the apsidal precession due to relativistic effects, during one period of revolution in radians, is

where c is the speed of light.[4] In the case of Mercury, half of the greater axis is about 5.79×1010 m, the eccentricity of its orbit is 0.206 and the period of revolution 87.97 days or 7.6×106 s. From these and the speed of light (which is ~3×108 m/s), it can be calculated that the apsidal precession during one period of revolution is ε = 5.028×10−7 radians (2.88×10−5 degrees or 0.104″). In one hundred years, Mercury makes approximately 415 revolutions around the Sun, and thus in that time, the apsidal perihelion due to relativistic effects is approximately 43″, which corresponds almost exactly to the previously unexplained part of the measured value.

انظر أيضا

الهامش

- ^ David M. Kipping (8 August 2011). The Transits of Extrasolar Planets with Moons. Springer. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-3-642-22269-6. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ Kane, S. R.; Horner, J.; von Braun, K. (2012). "Cyclic Transit Probabilities of Long-period Eccentric Planets due to Periastron Precession". The Astrophysical Journal. 757 (1): 105. arXiv:1208.4115. Bibcode:2012ApJ...757..105K. doi:10.1088/0004-637x/757/1/105.

- ^ Richard Fitzpatrick (30 June 2012). An Introduction to Celestial Mechanics. Cambridge University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-107-02381-9. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ^ Hawking, Stephen. On the Shoulders of Giants : the Great Works of Physics and Astronomy. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA: Running Press. pp. 1243, Foundation of the General Relativity (translated from Albert Einstein's Die Grundlage der Allgemeine Relativitätstheorie, first published in 1916 in Annalen der Physik, volume 49). ISBN 0-7624-1348-4.

المصادر

- مؤمن, عبد الأمير (2006). قاموس دار العلم الفلكي. بيروت، لبنان: دار العلم للملايين.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|طبعة أولى coauthors=(help)