الغزو الأمريكي لأفغانستان

| الغزو الأمريكي لأفغانستان | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جزء من War in Afghanistan and the War on terror | |||||||

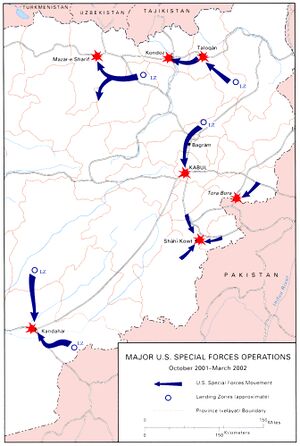

Map of the main operations of the United States special forces from October 2001 to March 2002, including Afghan velayat borders | |||||||

| |||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The United States invasion of Afghanistan occurred after the September 11 attacks in late 2001[1] and was supported by close US allies which had officially began the War on Terror. The conflict is also known as the US war in Afghanistan[2] or the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan. Its public aims were to dismantle al-Qaeda and deny it a safe base of operations in Afghanistan by removing the Taliban from power.[3] The United Kingdom was a key ally of the United States, offering support for military action from the start of preparations for the invasion. It followed the Afghan Civil War's 1996–2001 phase between the Taliban and the Northern Alliance groups, although the Taliban controlled 90% of the country by 2001. The US invasion of Afghanistan became the first phase of the War in Afghanistan (2001–present).

US President George W. Bush demanded that the Taliban hand over Osama bin Laden and expel al-Qaeda; bin Laden had already been wanted by the FBI since 1998. The Taliban declined to extradite him unless given what they deemed convincing evidence of his involvement in the 9/11 attacks,[4] and ignored demands to shut down terrorist bases and hand over other terrorist suspects apart from bin Laden. The request was dismissed by the US as a meaningless delaying tactic, and it launched Operation Enduring Freedom on October 7, 2001, with the United Kingdom. The two were later joined by other forces, including the Northern Alliance troops on the ground.[5][6] The US and its allies rapidly drove the Taliban from power by December 17, 2001, and built military bases near major cities across the country. Most al-Qaeda and Taliban members were not captured, escaping to neighboring Pakistan or retreating to rural or remote mountainous regions during the Battle of Tora Bora.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In December 2001, the United Nations Security Council established the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to oversee military operations in the country and train Afghan National Security Forces. At the Bonn Conference in December 2001, Hamid Karzai was selected to head the Afghan Interim Administration, which after a 2002 loya jirga (grand assembly) in Kabul became the Afghan Transitional Administration. In the popular elections of 2004, Karzai was elected president of the country, now named the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.[7] In August 2003, NATO became involved as an alliance, taking the helm of ISAF.[8] One portion of US forces in Afghanistan operated under NATO command; the rest remained under direct US command. Taliban leader Mullah Omar reorganized the movement, and in 2002, it launched an insurgency against the government and ISAF that continues to this day.[9][10]

أصول الحرب الأهلية الأفغانية

Afghanistan's political order began to break down with the overthrow of King Zahir Shah by his cousin Mohammed Daoud Khan in a bloodless 1973 coup. Daoud Khan had served as prime minister since 1953 and promoted economic modernization, emancipation of women, and Pashtun nationalism. This was threatening to neighboring Pakistan, faced with its own restive Pashtun population. In the mid-1970s, Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto began to encourage Afghan Islamic leaders, such as Burhanuddin Rabbani and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, to fight against the regime. In 1978, Daoud Khan was killed in a coup by Afghan's Communist Party, his former partner in government, known as the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). The PDPA pushed for a socialist transformation by abolishing arranged marriages, promoting mass literacy and reforming land ownership. This undermined the traditional tribal order and provoked opposition from Islamic leaders across rural areas, but it was particularly the PDPA's crackdown that contributed to open rebellion, including Ismail Khan's Herat Uprising. The PDPA was beset by internal leadership differences and was weakened by an internal coup on September 11, 1979, when Hafizullah Amin ousted Nur Muhammad Taraki. The Soviet Union, sensing PDPA weakness, intervened militarily three months later, to depose Amin and install another PDPA faction led by Babrak Karmal.

The entry of the Soviet Union into Afghanistan in December 1979 prompted its Cold War rivals, the United States, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and China, to support rebels fighting against the Soviet-backed Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. In contrast to the secular and socialist government, which controlled the cities, religiously motivated mujahideen held sway in much of the countryside. Beside Rabbani, Hekmatyar, and Khan, other mujahideen commanders included Jalaluddin Haqqani. The CIA worked closely with Pakistan's Inter-Service Intelligence to funnel foreign support for the mujahideen. The war also attracted Arab volunteers, known as "Afghan Arabs", including Osama bin Laden.

After the withdrawal of the Soviet military from Afghanistan in May 1989, the PDPA regime under Najibullah held on until 1992, when the collapse of the Soviet Union deprived the regime of aid, and the defection of Uzbek general Abdul Rashid Dostum cleared the approach to Kabul. With the political stage cleared of Afghan socialists, the remaining Islamic warlords vied for power. By then, Bin Laden had left the country. The United States' interest in Afghanistan also diminished.

Warlord rule (1992–1996)

In 1992, Rabbani officially became president of the Islamic State of Afghanistan, but had to battle other warlords for control of Kabul. In late 1994, Rabbani's defense minister, Ahmad Shah Massoud, defeated Hekmatyr in Kabul and ended ongoing bombardment of the capital.[11][12][13] Massoud tried to initiate a nationwide political process with the goal of national consolidation. Other warlords, including Ismail Khan in the west and Dostum in the north, maintained their fiefdoms.

In 1994, Mullah Omar, a Pashtun mujahideen who taught at a Pakistani madrassa, returned to Kandahar and founded the Taliban. His followers were religious students, known as the Talib, and they sought to end warlord-ism through strict adherence to Islamic law. By November 1994, the Taliban had captured all of Kandahar Province. They declined the government's offer to join in a coalition government and marched on Kabul in 1995.[14]

Taliban Emirate vs. Northern Alliance

The Taliban's early victories in 1994 were followed by a series of costly defeats.[15] Pakistan provided strong support to the Taliban.[16][17] Analysts such as Amin Saikal described the group as developing into a proxy force for Pakistan's regional interests, which the Taliban denied.[16] The Taliban started shelling Kabul in early 1995, but were driven back by Massoud.[12][18]

On September 27, 1996, the Taliban, with military support by Pakistan and financial support from Saudi Arabia, seized Kabul and founded the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.[19] They imposed their fundamentalist interpretation of Islam in areas under their control, issuing edicts forbidding women to work outside the home, attend school, or to leave their homes unless accompanied by a male relative.[20] According to the Pakistani expert Ahmed Rashid, "between 1994 and 1999, an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 Pakistanis trained and fought in Afghanistan" on the side of the Taliban.[21][22]

Massoud and Dostum, former arch-enemies, created a United Front against the Taliban, commonly known as the Northern Alliance.[23] In addition to Massoud's Tajik force and Dostum's Uzbeks, the United Front included Hazara factions and Pashtun forces under the leadership of commanders such as Abdul Haq and Haji Abdul Qadir. Abdul Haq also gathered a limited number of defecting Pashtun Taliban.[24] Both agreed to work together with the exiled Afghan king Zahir Shah.[22] International officials who met with representatives of the new alliance, which the journalist Steve Coll referred to as the "grand Pashtun-Tajik alliance", said, "It's crazy that you have this today … Pashtuns, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Hazara … They were all ready to buy in to the process … to work under the king's banner for an ethnically balanced Afghanistan."[25][26] The Northern Alliance received varying degrees of support from Russia, Iran, Tajikistan and India.

The Taliban captured Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998 and drove Dostum into exile.

The conflict was brutal. According to the United Nations (UN), the Taliban, while trying to consolidate control over northern and western Afghanistan, committed systematic massacres against civilians. UN officials stated that there had been "15 massacres" between 1996 and 2001. The Taliban especially targeted the Shiite Hazaras.[27][28] In retaliation for the killing of 3,000 Taliban prisoners by Uzbek general Abdul Malik Pahlawan in 1997, the Taliban killed about 4,000 civilians after taking Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998.[29][30]

Bin Laden's so-called 055 Brigade was responsible for mass-killings of Afghan civilians.[31] The report by the United Nations quotes eyewitnesses in many villages describing "Arab fighters carrying long knives used for slitting throats and skinning people".[27][28]

By 2001, the Taliban controlled as much as 90% of the country, with the Northern Alliance confined to the country's northeast corner. Fighting alongside Taliban forces were some 28,000–30,000 Pakistanis and 2,000–3,000 Al Qaeda militants.[14][31][32][33] Many of the Pakistanis were recruited from madrassas.[31] A 1998 document by the US State Department confirmed that "20–40 percent of [regular] Taliban soldiers are Pakistani." The document said that many of the parents of those Pakistani nationals "know nothing regarding their child's military involvement with the Taliban until their bodies are brought back to Pakistan". According to the US State Department report and reports by Human Rights Watch, other Pakistani nationals fighting in Afghanistan were regular soldiers, especially from the Frontier Corps, but also from the army providing direct combat support.[17][34] The 055 Brigade had at least 500 men during the time of the invasion, at least 1,000 more Arabs were believed to have arrived in Afghanistan following the September 11 Attacks, crossing over from Pakistan and Iran, many were based at Jalalabad, Khost, Kandahar and Mazar-i Sharif. There were rumors in the weeks before the September 11 attacks that Juma Namangani, had been appointed as one of the top commanders in the 055 brigade.[35]

Al-Qaeda

In August 1996, Bin Laden was forced to leave Sudan and arrived in Jalalabad, Afghanistan. He had founded al-Qaeda in the late 1980s to support the mujahideen's war against the Soviets, but became disillusioned by infighting among warlords. He grew close to Mullah Omar and moved Al Qaeda's operations to eastern Afghanistan.

The 9/11 Commission in the US reported found that under the Taliban, al-Qaeda was able to use Afghanistan as a place to train and indoctrinate fighters, import weapons, coordinate with other jihadists, and plot terrorist actions.[36] While al-Qaeda maintained its own camps in Afghanistan, it also supported training camps of other organizations. An estimated 10,000 to 20,000 men passed through these facilities before 9/11, most of whom were sent to fight for the Taliban against the United Front. A smaller number were inducted into al-Qaeda.[37]

After the August 1998 US Embassy bombings were linked to bin Laden, President Bill Clinton ordered missile strikes on militant training camps in Afghanistan. US officials pressed the Taliban to surrender bin Laden. In 1999, the United Nations Security Council imposed sanctions on the Taliban, calling for Bin Laden to be surrendered.[38] The Taliban repeatedly rebuffed these demands, though there were reports about attempts to negotiate the delivery of Bin Laden by the Taliban.[39][40][مرجع دائرة مفرغة][41]

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Special Activities Division paramilitary teams were active in Afghanistan in the 1990s in clandestine operations to locate and kill or capture Osama bin Laden. These teams planned several operations, but did not receive the order to proceed from President Clinton. Their efforts built relationships with Afghan leaders that proved essential in the 2001 invasion.[42]

Change in US policy toward Afghanistan

During the Clinton administration, the US tended to favor Pakistan and until 1998–1999 had no clear policy toward Afghanistan. In 1997, for example, the US State Department's Robin Raphel told Massoud to surrender to the Taliban. Massoud responded that, as long as he controlled an area the size of his hat, he would continue to defend it from the Taliban.[14] Around the same time, top foreign policy officials in the Clinton administration flew to northern Afghanistan to try to persuade the United Front not to take advantage of a chance to make crucial gains against the Taliban. They insisted it was the time for a cease-fire and an arms embargo. At the time, Pakistan began a "Berlin-like airlift to resupply and re-equip the Taliban", financed with Saudi money.[43]

US policy toward Afghanistan changed after the 1998 US embassy bombings. Subsequently, Osama bin Laden was indicted for his involvement in the embassy bombings. In 1999 both the US and the United Nations enacted sanctions against the Taliban via United Nations Security Council Resolution 1267, which demanded the Taliban surrender Osama bin Laden for trial in the US and close all terrorist bases in Afghanistan.[44] The only collaboration between Massoud and the US at the time was an effort with the CIA to trace bin Laden following the 1998 bombings.[45] The US and the European Union provided no support to Massoud for the fight against the Taliban.

By 2001 the change of policy sought by CIA officers who knew Massoud was underway.[46] CIA lawyers, working with officers in the Near East Division and Counter-terrorist Center, began to draft a formal finding for President George W. Bush's signature, authorizing a covert action program in Afghanistan. It would be the first in a decade to seek to influence the course of the Afghan war in favor of Massoud.[19] Richard A. Clarke, chair of the Counter-Terrorism Security Group under the Clinton administration, and later an official in the Bush administration, allegedly presented a plan to incoming Bush National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice in January 2001.

A change in US policy was effected in August 2001.[19] The Bush administration agreed on a plan to start supporting Massoud. A meeting of top national security officials agreed that the Taliban would be presented with an ultimatum to hand over bin Laden and other al-Qaeda operatives. If the Taliban refused, the US would provide covert military aid to anti-Taliban groups. If both those options failed, "the deputies agreed that the United States would seek to overthrow the Taliban regime through more direct action."[47]

Northern Alliance on the eve of 9/11

Ahmad Shah Massoud was the only leader of the United Front in Afghanistan. In the areas under his control, Massoud set up democratic institutions and signed the Women's Rights Declaration.[48] As a consequence, many civilians had fled to areas under his control.[49][50] In total, estimates range up to one million people fleeing the Taliban.[51]

In late 2000, Massoud officially brought together this new alliance in a meeting in Northern Afghanistan to discuss "a Loya Jirga, or a traditional council of elders, to settle political turmoil in Afghanistan".[52] That part of the Pashtun-Tajik-Hazara-Uzbek peace plan did eventually develop. Among those in attendance was Hamid Karzai.[53][54]

In early 2001, Massoud, with other ethnic leaders, addressed the European Parliament in Brussels, asking the international community to provide humanitarian help to the people of Afghanistan.[51] He said that the Taliban and al-Qaeda had introduced "a very wrong perception of Islam" and that without the support of Pakistan and Osama bin Laden, the Taliban would not be able to sustain their military campaign for another year.[51] On this visit to Europe, he warned that his intelligence had gathered information about an imminent, large-scale attack on US soil.[55]

On September 9, 2001, Massoud was critically wounded in a suicide attack by two Arabs posing as journalists, who detonated a bomb hidden in their video camera during an interview in Khoja Bahauddin, in the Takhar Province of Afghanistan.[56][57] Massoud died in the helicopter taking him to a hospital. The funeral, held in a rural area, was attended by hundreds of thousands of mourning Afghans.

September 11, 2001, attacks

On the morning of September 11, 2001, al-Qaeda carried out four coordinated attacks on the United States, employing four commercial passenger jet airliners that were hijacked.[58][59] The hijackers – members of al-Qaeda's Hamburg cell[60] – intentionally crashed two of the airliners into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City. Both buildings collapsed within two hours from fire damage related to the crashes, destroying nearby buildings and damaging others. The hijackers crashed a third airliner into the Pentagon in Arlington County, Virginia. The fourth plane crashed into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, after some of its passengers and flight crew attempted to retake control of the plane, which the hijackers had redirected toward Washington, D.C., to target the White House or the United States Capitol. No flights had survivors. In total, 2,996 people died, including the 19 hijackers, and more than 6,000 others were injured in the attacks.[61] According to the New York State Health Department, 836 first responders, including firefighters and police personnel, had died as of June 2009.[61]

On September 11, Taliban foreign minister Wakil Ahmed Muttawakil "denounce[d] the terrorist attack, whoever is behind it",[62] but Mullah Omar immediately issued a statement saying bin Laden was not responsible.[63] The following day, President Bush called the attacks more than just "acts of terror" but "acts of war", and resolved to pursue and conquer an "enemy" that would no longer be safe in "its harbors".[64] The Taliban ambassador to Pakistan, Abdul Salam Zaeef, said on September 13, 2001, that the Taliban would consider extraditing bin Laden if there was solid evidence linking him to the attacks.[65] Though Osama bin Laden eventually took responsibility for the 9/11 attacks in 2004, he denied having any involvement in a statement issued on September 17, 2001, and by interview on September 29, 2001.[66][67]

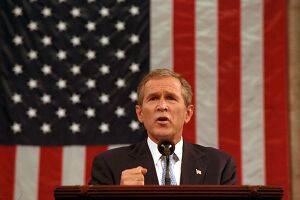

The State Department, in a memo dated September 14, demanded that the Taliban surrender all known al-Qaeda associates in Afghanistan, provide intelligence on bin Laden and his affiliates, and expel all terrorists from Afghanistan.[68] On September 18, the director of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence, Mahmud Ahmed conveyed these demands to Mullah Omar and the senior Taliban leadership, whose response was "not negative on all points".[69] Mahmud reported that the Taliban leadership was in "deep introspection" and waiting for the recommendation of a grand council of religious clerics that was assembling to decide the matter.[69] On September 20, President Bush, in an address to Congress, demanded the Taliban deliver bin Laden and other suspected terrorists and destroy the al-Qaeda bases.[70] "These demands are not open to negotiation or discussion. The Taliban must act and act immediately. They will hand over the terrorists, or they will share in their fate."[71]

On the same day, a grand council of over 1,000 Muslim clerics from across Afghanistan, which had convened to decide bin Laden's fate, issued a fatwa expressing sadness for the deaths in the 9/11 attacks, recommending that the Islamic Emirate "persuade" bin Laden to leave their country, and calling on the United Nations and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation to conduct an independent investigation of "recent events to clarify the reality and prevent harassment of innocent people".[72] The fatwa went on to warn that should the United States not agree with its decision and invade Afghanistan, "jihad becomes an order for all Muslims."[72] However, on the same day the Taliban ambassador to Pakistan said: "We will neither surrender Osama bin Laden nor ask him to leave Afghanistan." These maneuvers were dismissed by the US as insufficient.[73]

On September 21, Taliban representatives in Pakistan reacted to the US demands with defiance. Zaeef said the Taliban were ready, if necessary, for war with the United States. His deputy Suhail Shaheen warned that a US invasion would share in the same fate that befell Great Britain and the Soviet Union in previous centuries. He confirmed that the clerics' decision "was only a recommendation" and bin Laden would not be asked to leave Afghanistan. But he suggested "If the Americans provide evidence, we will cooperate with them... In America, if I think you are a terrorist, is it properly justified that you should be punished without evidence?", he asked. "This is an international principle. If you use the principle, why do you not apply it to Afghanistan?" As formulated earlier by Mullah Omar, the demand for evidence was attached to a suggestion that bin Laden be handed over for trial before an Islamic court in another Muslim country.[74] He did not address the demands to hand over other suspected terrorists or shut down training camps.

On September 24, Mahmoud told the US Ambassador to Pakistan that while the Taliban was "weak and ill-prepared to face the American onslaught", "real victory will come through negotiations", for if the Taliban were eliminated, Afghanistan would revert to warlord-ism.[75] On September 28, he led a delegation of eight Pakistani religious leaders to persuade Mullah Omar to accept having religious leaders from Islamic countries examine the evidence and decide bin Laden's fate, but Mullah Omar refused.[76][77]

On September 28 Bush commented, "First, there is no negotiations [sic] with the Taliban. They heard what I said. And now they can act. And it's not just Mr. bin Laden that we expect to see and brought [sic] to justice; it's everybody associated with his organization that's in Afghanistan. And not only those directly associated with Mr. bin Laden, any terrorist that is housed and fed in Afghanistan needs to be handed over. And finally, we expect there to be complete destruction of terrorist camps. That's what I told them; that's what I mean. And we expect them — we expect them to not only hear what I say but to do something about it."[78]

On October 1, Mullah Omar agreed to a proposal by Qazi Hussain Ahmad, the head of Pakistan's most important Islamic party, the Jamaat-i-Islami, to have bin Laden taken to Pakistan, where he would be held under house arrest in Peshawar and tried by an international tribunal within the framework of sharia law. The proposal was said to have bin Laden's approval. Pakistan's president Pervez Musharraf blocked the plan because he could not guarantee bin Laden's safety.[79] On October 2, Zaeef appealed to the United States to negotiate, "We do not want to compound the problems of the people, the country or the region." He pleaded, "the Afghan people need food, need aid, need shelter, not war." However, he reiterated that bin Laden would not be turned over to anyone unless evidence was presented.[80]

A US State Department spokesman in response to a question about sharing evidence with the Taliban stated, "My response, first of all, is that strikes me as a request for delay and prevarication rather than any serious request. And second of all, they're already overdue. They are already required by the United Nations resolutions that relate to the bombings in East Africa to turn over al-Qaeda, to turn over their leadership, and to shut down the network of operations in their country. There should be no further delay. There is no cause to ask for anything else. They are already under this international obligation, and they have to meet it."[81] The British Prime Minister Tony Blair called on the Taliban to "surrender the terrorists or surrender power".[82]

Nonetheless, some evidence of bin Laden's involvement in the 9/11 attacks was shown to Pakistan's government, whose leaders later stated that the materials they had seen "provide[d] sufficient basis for indictment in a court of law".[83] Pakistan ISI chief Lieutenant General Mahmud Ahmed shared information provided to him by the US with Taliban leaders.[84] On October 4 the British government publicly released a document summarizing the evidence linking bin Laden to the attacks.[85] The document stated that the Taliban had been repeatedly warned in the past about harboring bin Laden but refused to turn him over as demanded by the international community. Evidence had been supplied to the Taliban about bin Laden's involvement in the 1998 Embassy bombings, yet they did nothing.[86]

On October 5, the Taliban offered to try bin Laden in an Afghan court, so long as the US provided what it called "solid evidence" of his guilt.[87] The US Government dismissed the request for proof as "request for delay or prevarication"; NATO commander George Robertson said the evidence was "clear and compelling".[82] On October 7, as the US aerial bombing campaign began, President Bush ignored questions about the Taliban's offer and said instead, "Full warning had been given, and time is running out."[88] The same day, the State Department gave the Pakistani Government one last message to the Taliban: Hand over all al-Qaeda leaders or "every pillar of the Taliban regime will be destroyed."[89]

On October 11 Bush told the Taliban "You still have a second chance. Just bring him in, and bring his leaders and lieutenants and other thugs and criminals with him."[90] On October 14, Abdul Kabir, the Taliban's third ranking leader, offered to hand over bin Laden to a neutral third country if the US government provided evidence of his guilt and halted the bombing campaign. He apparently did not respond to the demand to hand over other suspected terrorists apart from bin Laden. President Bush rejected the offer as non-negotiable.[91] On October 16, Muttawakil, the Taliban foreign minister floated a compromise offer that dropped the demand for evidence.[92] However, Muttawakil was not part of the Taliban's inner circle; he wanted the bombing to stop so that he could try to persuade Mullah Omar to adopt a compromise.[93]

Legal basis for war

On September 14, 2001, Congress passed legislation titled Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists, which was signed on September 18, 2001, by President Bush. It authorized the use of US Armed Forces against those responsible for the 9/11 attacks and those who harbored them.[94]

Article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter, to which all Coalition countries are signatories and for which its ratification by the US makes it the "law of the land",[95] prohibits the 'threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state' except in circumstances where a competent organ of the UN (e.g. the Security Council) has authorized it, or where it is in self-defense under article 51 of the Charter.[96] Although the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) did not authorize the US-led military campaign, some argued it was a legitimate form of self-defense under the UN Charter.[96]

Some proponents of the legality of the invasion argued that UNSC authorization was not required, since the invasion was an act of collective self-defense provided for under Article 51 of the UN Charter.[96][97] Specifically, it was argued that a series of UN Security Council Resolutions concerning Afghanistan provided for the possibility of establishing that the Taliban were indirectly responsibility for al-Qaeda's attacks, on the basis that Afghanistan was offering them safe harbour. Some critics claimed that the invasion was illegal under Article 51 because the 9/11 attacks were not "armed attacks" by another state, as required under article 51 of the Charter: they were not perpetrated by Afghanistan but by non-state actors. They argued that the actions taken by the terrorists in 9/11 were not attributable to Afghanistan. This position is consistent with the case law of the International Court of Justice, also known as the World Court, which has been slow to recognize attacks carried out by non-State actors as attributable to States, even in cases where States lend their support to the actions of non-State actors.[98] Others claimed that, even if the 9/11 attacks were attributable to Afghanistan, the response of the NATO coalition would not constitute self-defense as these acts do not meet the proportionality test under international law, as established in the Caroline Affair.

On December 20, 2001, more than two months after the attack began, the UNSC authorized the creation of International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to assist the Afghan Interim Authority in maintaining security.[99] This resolution did not make any express declarations as to the legality of the war but determined that "the situation in Afghanistan still constituted a threat to international peace and security" while "reaffirming its strong commitment to the sovereignty, independence, territorial integrity and national unity of Afghanistan".

2001: Overthrow of the Taliban

Command Structure

Under the overall leadership of General Tommy Franks, Commander-in-Chief, US Central Command, four major task forces were raised to support Operation Enduring Freedom: the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force (CJSOTF), Combined Joint Task Force Mountain(CJTF-Mountain), the Joint Interagency Task Force-Counterterrorism (JIATF-CT), and the Coalition Joint Civil-Military Operations Task Force (CJCMOTF).[100]

CJSOTF was a mixture of black and white SOF and comprised three subordinate task forces: Joint Special Operations Task Force-North (JSOTF-North - known as Task Force Dagger), Joint Special Operations Task Force-South (JSOTF-South - known as Task Force K-Bar) and Task Force Sword (later renamed Task Force 11).[100] Task Force Dagger was established on October 10, 2001, led by Colonel James Mulholland and was formed around his 5th Special Forces Group with helicopter support from the 160th SOAR, Dagger was assigned to the north of Afghanistan.[100] Task Force K-Bar, also established on October 10, was assigned to Southern Afghanistan, led by Navy SEAL Captain Robert Harward and formed around a Naval Special Warfare Group consisting of SEAL Teams 2, 3 and 8 and Green Berets from 1st Battalion, 3rd Special Forces Group. The Task force principally conducted SR and SSE missions, although some 3rd SFG ODAs were given to the foreign internal defense and unconventional warfare role - advising anti-Taliban militias.[101] Task Force Sword, established in early October 2001, was a black SOF unit under direct command of Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC). This was a so-called hunter-killer force whose primary objective was capturing or killing senior leadership and High-value target (HVT) within both al-Qaeda and the Taliban. Sword was initially structure around a two-squadron component of operators from Delta Force (Task Force Green) and DEVGRU (Task Force Blue) supported by a Ranger protection force teams (Task Force Red) and ISA signals intercept and surveillance operators (Task Force Orange) and the 160th SOAR (Task Force Brown). The British Special Boat Service was integrated directly into Swords structure.[102]

Alongside the SOF task forces operated the largely conventional CJTF-Mountain. Mountain initially comprised three subordinate commands, but only one was a special operations force - Task Force 64, a special forces task group built around a sabre squadron from the Australian SAS. The US Marines contributed Task Force 58, consisting of the 15th MEU, who were later replaced by Task Force Rakkasan. The JIATF-CT (better known as Task Force Bowie), led by Brigadier General Gary Harrell, was an intelligence integration and fusion activity manned by personnel from all Operation Enduring Freedom – Afghanistan (OEF-A) participating units, both US, coalition and a number of civilian intelligence and law enforcement agencies. Bowie numbered 36 military personnel and 57 from agencies such as FBI, NSA, and CIA, as well as liaison officers from coalition SOF. Administratively embedded within Bowie was Advanced Force Operations (AFO). AFO was a 45-man reconnaissance unit made up of Delta Force reconnaissance specialists augmented by selected SEALs from DEVGRU and supported by ISA's technical experts. AFO had been raised to support TF Sword and was tasked with intelligence preparation of the battlefield, working closely with the CIA and reported directly to TF Sword. AFO conducted covert reconnaissance - sending small 2 or 3 man teams into al-Qaeda 'Backyard' along the border with Pakistan, the AFO operators would deploy observation posts to watch and report enemy movements and numbers as well as environmental reconnaissance; much of the work was done on foot or ATVs. The final task force supporting OEF-A was CJCMOTF, which had the responsibility of managing civil affairs and humanitarian efforts.[103]

First move

On September 26, 2001, fifteen days after the 9/11 attack, the US covertly inserted (by a CIA-piloted Mi-17 helicopter) seven or eight[104] members of the CIA's Special Activities Division and Counterterrorism Center (CTC) into the Panjshir Valley, north of Kabul. Led by Gary Schroen, the team included deputy commander and former Special Forces captain[105] Phil Reilly,[106] a former Navy special warfare operator; a former Army paratrooper; and “Todd, a former Marine and the team communicator.”[107] They formed the Northern Afghanistan Liaison Team, known by the call-sign 'Jawbreaker'.[108][109][110][111] In addition to specialized human assets, the team brought three cardboard boxes filled with $3 million in $100 bills to buy support.[112] Jawbreaker linked up with General Mohammed Fahim, commander of the Northern Alliance forces in the Panjshir Valley, and prepared the way for the introduction of Army Special Forces into the region.[113][114][110][115] The Jawbreaker team brought satellite communications enabling its intelligence reports to be instantly available to headquarters staff at Langley and Central Command (CENTCOM), who were responsible for Operation Crescent Wind and Operation Enduring Freedom. The Team also assessed potential targets for Operation Crescent Wind, provide an in-extremis CSAR and could provide BDA for the air campaign.[116]

On September 28, 2001, British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw approved the deployment of MI6 officers to the Afghanistan and the region, utilising people involved with the mujahadeen in the 1980s, and who had language skills and regional expertise. At the end of the month, a handful of MI6 officers with a budget of $7 million landed in northeast Afghanistan, they met with General Mohammed Fahim of the Northern Alliance and began working with other contacts in the north and south to build alliances, to secure support and to bribe as many Taliban commanders as they could to change sides or leave the fight.[117]

Initial air strikes

On October 7, 2001, the US officially launched military operations in Afghanistan. Airstrikes were reported in Kabul, at the airport, at Kandahar (home of Mullah Omar), and in the city of Jalalabad.[118] The day before the bombing commenced, Human Rights Watch issued a report urging that no military support be given to the Northern Alliance due to their human rights record.[119]

At 17:00 UTC, President Bush confirmed the strikes in his address to the nation, and Prime Minister Blair also addressed his nation. Bush stated that Taliban military sites and terrorist training grounds would be targeted. Food, medicine and supplies would be dropped to "the starving and suffering men, women and children of Afghanistan".[120] Most of the Taliban's outdated SA-2 and SA-3 surface to air missiles, as well as its intended radar and command units, were destroyed on the first night along with the Taliban's small fleet of MIG-21s and Su-22s.[121]

Training camps and Taliban air defenses were bombarded by US aircraft, including Apache helicopter gunships from the 101st Combat Aviation Brigade. US Navy cruisers, destroyers and Royal Navy submarines launched several Tomahawk cruise missiles.

The strikes initially focused on Kabul, Jalalabad and Kandahar. Within a few days, most Taliban training sites were severely damaged and air defenses were destroyed. The campaign focused on command, control, and communications targets. The front facing the Northern Alliance held, and no battlefield successes were achieved there.

During these initial airstrikes a garrison of the 055 brigade near Mazar-i-Sharif was one of the first targets for US aircraft. Donald Rumsfeld described the troops as "the al-Qaeda-dominated ground force".[35]

Earlier Bin Laden had released a video in which he condemned all attacks in Afghanistan.

On October 18, 2001,[103] Operational Detachment Alpha (ODA) teams 555 and 595, both 12-man Green Beret teams from the 5th Special Forces Group, plus Air Force Combat Controllers, were airlifted by helicopter from the Karshi-Khanabad Air Base in Uzbekistan[113] more than 300 kilometers (190 mi) across the 16,000 feet (4,900 m) Hindu Kush mountains in zero-visibility conditions by two MH-47E Chinook helicopters from 2nd Battalion 160th SOAR to the Dari-a-Souf Valley, just south of Mazar-e-Sharif.[122] The Chinooks were refueled in-flight three times during the 11-hour mission, establishing a new world record for combat rotor-craft missions at the time. They linked up with the CIA and Northern Alliance. Within a few weeks the Northern Alliance, with assistance from the US ground and air forces, captured several key cities from the Taliban.[115][123][124]

In mid-October 2001, A and G squadron of the British 22nd SAS Regiment, reinforced by members of the Territorial SAS regiments, deployed to north west Afghanistan in support of OEF-A. They conducted largely uneventful reconnaissance tasks under the code-name Operation Determine, none of these tasks resulted in enemy contact; they traveled in Land Rover Desert Patrol Vehicles (known as Pinkies) and modified ATVs. After a fortnight, with missions drying up, both squadrons returned to their barracks in the UK.[125]

Objective Rhino and Gecko

On the night of October 19, 2001, 200 Rangers from the 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, parachuted from 4 Lockheed MC-130 aircraft onto "Objective Rhino", a landing strip south of Kandahar, covered by AC-130 gunships. Before the Rangers dropped, the site was softened up by B-2 Spirit stealth bombers. The Rangers met almost no resistance, except for a solitary Taliban fighter who was quickly killed, securing the objective. A small Taliban force mounted in pick up trucks that attempted to investigate was spotted and destroyed by the AC-130s. The Rangers provided security while a FARP (Forward Arming and Refuelling Point) was established using fuel bladders from MC-130s; the mission paved the way for the later use of the airstrip by the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit as FOB Rhino, who would be among the first conventional forces to set foot in Afghanistan. No casualties were suffered in the operation itself (two Rangers received minor injuries in the jump itself), though two Rangers assigned to a CSAR element supporting the mission were killed when their MH-60L helicopter crashed at Objective Honda in Pakistan, a temporary staging site used by a company of Rangers from 3/75. The helicopter crashed due to a brownout.[126]

At the same time, a squadron of Delta Force operatives supported by Rangers from Task Force Sword conducted an operation outside of Kandahar at a location known as Objective Gecko – its target was Mullah Omar, who was suspected to be at his summer retreat in the hills above Kandahar.[127] Four MH-47E helicopters took off from the USS Kitty Hawk (which was serving as an SOF base) in the Indian Ocean carrying 91 soldiers. The assault teams were drawn from Delta, while teams from the Rangers secured the perimeter and manned blocking positions. Before the soldiers were inserted, the target area was softened up by preparatory fire from AC-130s and MH-60L Direct Action Penetrators. The assaulters met no resistance on target and there was no sign of the Taliban leader, so they switched to exploiting the target location for any intelligence, while their helicopters landed at Rhino to refuel at the newly established FARP. As the teams prepared to extract, a sizable Taliban force approached the compound and engaged the US force with small arms fire and RPGs.[128] The Delta Force operators and Rangers engaged the insurgents and a heavy firefight developed. An attached Combat Controller directed fire from the orbiting AC-130s and DAPs, allowing the assault force to break contact and withdraw to an emergency Helicopter Landing Zone (HLZ). One of the MH-47Es lost a wheel assembly after striking the compound wall in the scramble to extract the ground force. Some 30 Taliban fighters were killed in the firefight; there were no US soldiers killed, but 12 Delta operators were wounded.[127] Delta's plans to leave a stay-behind reconnaissance team in the area were aborted by the Taliban response.[129]

Continued air strikes

The Green Berets of ODA 595 split into two elements, Alpha and Bravo. Alpha rode on horseback with the Uzbek Warlord General Dostum to his headquarters to plan the impending assault on Mazar-e-Sharif. Bravo was tasked with clearing the Dari-a-Souf Valley of Taliban and to travel into the Alma Tak Mountains to get a good look at its area of operations.[130]

On October 20, 2001, the Alpha element of ODA 595 guided in the first JDAM bomb from a B-52, impressing Dostum, who soon taunted the Taliban over their radio frequencies.[130] As part of its operations, the Americans beamed in radio broadcasts in both Pashto and Dari calling al-Qaeda and the Taliban criminals who were not proper Muslims and promising US$25 million to anyone who would provide information leading to the whereabouts of bin Laden.[131]

Two weeks into the campaign, the Northern Alliance demanded the air campaign focus more on the front lines. A number of units from the US 5th Special Forces Group Operational Detachment Alpha teams were accompanied by a USAF Tactical Air Control Party. They called in air strikes on targets, pounding Taliban vehicles, antiaircraft weapons, armored vehicles, their trenches, and ammunition supplies.

On October 23, ODA 585 infiltrated an area near Kunduz to work alongside the warlord Burillah Khan.[132]

The United States conducted its own psychological warfare operation with EC-130E Commando Solo aircraft beaming radio transmissions in both Dari and Pashtu to the Afghan civilian population. Radios were dropped with humanitarian packages that were fixed to only receive news and Afghan music from a Coalition radio station. Air Force Special Operations aircraft also dropped huge numbers of Psy Ops leaflets, decrying the Taliban and al-Qaeda as criminals who ruined Afghanistan and promoting the $25 million reward placed on Bin Laden's head.[133]

Carrier-based F/A-18 Hornet fighter-bombers hit Taliban vehicles in pinpoint strikes, while other aircraft cluster bombed Taliban defenses. At the beginning of November, US aircraft attacked front lines with daisy cutter bombs and AC-130 gunships.

By November 2, Taliban frontal positions were devastated and a march on Kabul seemed possible. According to author Stephen Tanner,

After a month of the U.S. bombing campaign rumblings began to reach Washington from Europe, the Mideast, and Pakistan where Musharraf had requested the bombing to cease. Having begun the war with the greatest imaginable reservoir of moral authority, the U.S. was on the verge of letting it slip away through high-level attacks using the most ghastly inventions its scientists could come up with.[134]

Also on November 2, the 10-man ODA 553 inserted into Bamain and linked up with General Kareem Kahlili's forces; ODA 534 was also inserted into the Dari-a-Balkh Valley after being delayed by weather for several nights, its role was to support General Mohammed Atta - the head of Jaamat-e-Islami militia. Alongside the Green Berets was a small element of CIA SAD operatives.[132]

Bravo team of ODA 595 conducted its own airstrikes in the Dari-a-Souf Valley, cutting off and destroying Taliban reinforcements and frustrating its attempts to relieve its embattled forces in the north. Cumulatively, the near constant airstrikes had begun to have a decisive effect and the Taliban began to withdraw toward Mazar-e-Sharif. Dostum's forces and Alpha team of ODA 595 followed, pausing only to drop further bombs on Taliban stragglers using their Special Operations Forces Laser Marker (SOFLAM), a device that emits laser-aiming point that can be followed by a smart bomb, such as a JDAM.[133]

On the Shomali Plains, ODA 555 and the CIA Jawbreaker team attached to Fahim Khan's forces began calling in airstrikes on entrenched Taliban positions at the southeastern end of the former Soviet air base at Bagram. The Green Berets set up an observation post in a disused air traffic control tower and with perfect lines of sight, guided in two BLU-82 Daisy Cutter bombs which devastated the Taliban lines, both physically and psychologically. By November 5, 2001, the advance of Dostum and his force was stalled at the Taliban-held village of Bai Beche in the strategically vital Dari-a-Souf Valley. Two earlier Northern Alliance attacks had been driven back by the entrenched Taliban; Dostum prepared his men to follow a bombing run from a B-52 with a cavalry charge, but one of Dostum's lieutenants misunderstood an order and sent around 250 Uzbek horsemen charging toward the Taliban lines as the B-52 made its final approach, three or four bombs landed just in time on the Taliban positions and the cavalry charge succeeded in breaking the back of the Taliban defenders.[132]

On November 8, ODAs 586 and 594 were infiltrated into Afghanistan in MH-47s and picked up on the Afghan/Tajik border by CIA-flown MI-17s crewed by the SAD Air Branch contractors. ODA 586 deployed to Kunduz with the forces of General Daoud Khan and ODA 594 deployed into the Panjshir to assist the men of ODA 555.[135]

Bush went to New York City on November 10, 2001, to address the United Nations. He said that not only was the US in danger of further attacks, but so were all other countries in the world. Tanner observed, "His words had impact. Most of the world renewed its support for the American effort, including commitments of material help from Germany, France, Italy, Japan and other countries."[134]

Al-Qaeda fighters took over security in Afghan cities. The Northern Alliance troops planned to seize Mazar-i-Sharif, cutting off Taliban supply lines and enabling equipment to arrive from the north and then attack Kabul.

During the early months, the US military had a limited presence on the ground. Special Forces and intelligence officers with a military background liaised with Afghan militias and advanced after the Taliban was disrupted by air power.[136][137][138]

The Tora Bora Mountains lie roughly east of Kabul, on the Pakistan border. American analysts believed that the Taliban and Al-Qaeda had dug in behind fortified networks of caves and underground bunkers. The area was subjected to a heavy B-52 bombardment.[136][137][138][139]

US and Northern Alliance objectives began to diverge. While the US was continuing the search for Osama bin Laden, the Northern Alliance wanted to finish off the Taliban.

Battle of Mazar-i Sharif

Mazari-i Sharif was important because it is the home of the Shrine of Ali or "Blue Mosque", a sacred Muslim site, and because it is a significant transportation hub with two major airports and a major supply route leading into Uzbekistan.[140] Taking the city would enable humanitarian aid to alleviate a looming food crisis, which threatened more than six million people with starvation. Many of those in most urgent need lived in rural areas to the south and west of Mazar-i-Sharif.[140][141] On November 9, 2001, Northern Alliance forces, under the command of Dostum and Ustad Atta Mohammed Noor, overcame resistance crossing the Pul-i-Imam Bukhri bridge[142][143] and seized the city's main military base and airport.

ODA 595 and ODA 534 and the seven members of the CIA's Special Activities Division[111][144][145][146] assisted about 2000 members of the Northern Alliance who attacked Mazari Sharif on horseback, foot, pickup trucks, and BMP armored personnel carriers.[135] The US forces utilized close air support, which they used to destroy armor and vehicles. After a brief but bloody 90-minute battle, the Taliban withdrew, triggering celebrations.[141][147]

The fall of the city was a "body blow"[147] to the Taliban and ultimately proved to be a "major shock",[148] since the US Central Command (CENTCOM) had originally believed that the city would remain in Taliban hands well into the following year[149] and any potential battle would require "a very slow advance".[150]

US Army Civil Affairs Teams from the 96th Civil Affairs Battalion and Tactical Psychological Operations Teams from the 4th Psychological Operations Group assigned to both the Green Berets and Task Force Dagger were immediately deployed to Mazar-e-Sharif to assist in winning the hearts and minds of the inhabitants.[151]

Following rumors that Mullah Dadullah was headed to recapture the city with as many as 8,000 fighters, a thousand US troops of the 10th Mountain Division were airlifted into the city, providing the first solid position from which Kabul and Kandahar could be reached.[152] The US Air Force now had an airport to allow them to fly more sorties for resupply missions and humanitarian aid.[147][153]

US-backed forces began immediately broadcasting from Radio Mazar-i-Sharif, the former Taliban Voice of Sharia channel,[154] including an address from former President Rabbani.[155]

On November 10, operators from C squadron SBS inserted via two C-130s into the recently captured Bagram Airfield and caused an immediate political quandary with the Northern Alliance leadership, which claimed the British had failed to consult in on the deployment.[125][156] The British government had not given any forewarning or sought permission from the Northern Alliance of the deployment. The Northern Alliance foreign minister Abdullah Abdullah was "apoplectic" as he considered the uninvited arrival to be a violation of sovereignty, and complained bitterly to the head of the CIA field office, threatening to resign if the British did not withdraw. As it happened, the British government did alert the deputy head of the United Nations mission in Afghanistan that they were deploying troops to Bagram, albeit at short notice. Arriving on the first flight, Brigadier Graeme Lamb, then the Director Special Forces, simply ignored Abdullah and drove to the Panjshir Valley, where he paid his respects to Ahmad Shah Massoud's grave and held talks with Northern Alliance leaders. The British Foreign Secretary tried to reassure the Northern Alliance that the deployment was not a vanguard of a British peacekeeping army, but Northern Alliance leaders did not believe them; with the threat of the Northern Alliance opening fire on incoming RAF troop transports, the deployment was put on hold.[156]

On November 11, in the central north of Afghanistan, ODA 586 was advising General Daoud Khan outside the city of Taloqan and coordinating a batch of preparatory airstrikes when the General surprised everyone by launching an impromptu massed infantry assault on the Taliban holding the city. Before the first bomb could be dropped, the city fell.[151]

Fall of Kabul

On the night of November 12, Taliban forces fled Kabul under cover of darkness. Northern Alliance forces (supported by ODA 555)[157] arrived the following afternoon, encountering a group of about twenty fighters hiding in the city's park. This group was killed in a 15-minute gun battle. After these forces were neutralized, Kabul was in the hands of coalition forces.[158]

The fall of Kabul started a cascading collapse of Taliban positions. Within 24 hours, all Afghan provinces along the Iranian border had fallen, including Herat. Local Pashtun commanders and warlords had taken over throughout northeastern Afghanistan, including Jalalabad. Taliban holdouts in the north fell back to the northern city of Kunduz. By November 16, the Taliban's last stronghold in northern Afghanistan was under siege. Nearly 10,000 Taliban fighters, led by foreign fighters, continued to resist. By then, the Taliban had been forced back to their heartland in southeastern Afghanistan around Kandahar.[159]

Elsewhere in Afghanistan UK and US special forces joined the Northern Alliance and other Afghan opposition groups to take Herat in November 2001. Canada and Australia also deployed forces. Other countries provided basing, access and overflight permission.

As a result of all the losses, surviving members of the Taliban and al-Qaeda retreated toward Kandahar, the spiritual birthplace and home of the Taliban movement and Tora Bora.[157]

By November 13, al-Qaeda and Taliban forces, possibly including bin Laden, were concentrating in Tora Bora, 50 kilometres (31 mi) southwest of Jalalabad. Nearly 2,000 al-Qaeda and Taliban fighters fortified themselves in positions within bunkers and caves. On November 16 the US began bombing the mountain redoubt. Around the same time, CIA and Special Forces operatives were at work in the area, enlisting local warlords and planning an attack.[160]

Objective Wolverine, Raptor and Operation Relentless Strike

On November 13, the 75th Ranger Regiment carried out its second combat parachute drop into Afghanistan. A platoon-sized Ranger security element, including Team 3 of the Ranger Reconnaissance Detachment, accompanied by 8 Air Force Special Tactical operators, parachuted into a site southwest of Kandahar, codenamed Bastogne to secure a FARP for a follow on operation by the 160th SOAR. A pair of MC-130 cargo soon landed at the improvised airstrip and deposited four AH-6J Little Bird helicopters, the flight of little birds lifted off to hit a Taliban target compound near Kandahar code named Objective Wolverine. After destroying the target, the Little Birds returned to the FARP and proceeded to rearm and refuel and then they launched another strike against a second site called objective Raptor. With their mission completed, the Little Birds returned to the FARP, loaded onto the MC-130s and flew back to Pakistan. Several nights later, a similar mission codenamed Operation Relentless Strike took place – this time with the Rangers driving their modified HMMWV and Land Rovers to secure a remote desert strip. These were the first missions in Afghanistan conducted by the Little Bird pilots of the 160th SOAR, as the helicopters could not operate at the high altitudes in the mountains.[151]

Meanwhile, the US was able to track and kill al-Qaeda's number three, Mohammed Atef, with a bomb at his Kabul home between November 14–16, 2001, along with his guard Abu Ali al-Yafi'i and six others.[161][162]

Battle of Tarinkot

On November 14, 2001, ODA 574 and Hamid Karzai inserted into Uruzgan Province via 4 MH-60K helicopters[157] with a small force of guerrillas.[163] In response to the approach of Karzai's force, the inhabitants of the town of Tarinkot revolted and expelled their Taliban administrators. Karzai traveled to Tarinkot to meet with the town elders. While he was there, the Taliban marshaled a force of 500 men to retake Tarinkot. Karzai's small force plus the American contingent, which consisted of US Army Special Forces from ODA 574 and their US Air Force Combat Controller, Tech Sergeant Alex Yoshimoto,[164] were deployed in front of the town to block their advance. Relying heavily on close air support directed by Yoshimoto, the American/Afghan force managed to halt the Taliban advance and drive them away from the town.[165]

The defeat of the Taliban at Tarinkot was an important victory for Karzai, who used the victory to recruit more men to his fledgling guerrilla band. His force would grow in size to a peak of around 800 men. On November 30, they left Tarinkot and began advancing on Kandahar.

Fall of Kunduz

Task Force Dagger attention focused on the last northern Taliban stronghold, Kunduz;[157] as the bombardment at Tora Bora grew, the Siege of Kunduz was continuing. General Daoud and ODA 586 had initiated massive coalition airstrikes to demoralize the Taliban defenders.[157] After 11 days of fighting and bombardment, Taliban fighters surrendered to Northern Alliance forces on November 23. Shortly before the surrender, Pakistani aircraft arrived to evacuate intelligence and military personnel who had been aiding the Taliban's fight against the Northern Alliance. The airlift is alleged to have evacuated up to five thousand people, including Taliban and al-Qaeda troops.[166][167][168]

Operation Trent

After political intersession with Prime Minister Tony Blair, the SAS were given a direct-action task – the destruction of an al-Qaeda-linked opium plant. The facility was located 400 km (250 mi) southwest of Kandahar, manned by between 80 and 100 foreign fighters, with defenses consisting of trench lines and several makeshift bunkers. The SAS were ordered to assault the facility in full daylight: the timelines had been mandated by CENTCOM and were based on the availability of air support assets – only one hour of on-call close air support was provided. The timings meant that the squadrons could not carry out a detailed reconnaissance of the site prior to the assault being launched. Despite these factors, the commanding officer of 22 SAS accepted the mission. The Target was a low priority for the US and probably would have been destroyed from the air if the British hadn't argued for a larger role in Afghanistan; US SOF commanders guarded targets for their own units. The strategic significance of the facility has never fully been explained.[169]

The mission began in November 2001, with an 8-man patrol from G Squadron's Air Troop performing the regiments first wartime HALO parachute jump - onto a barren desert site in Registan to test its suitability as an improvised airstrip for the landing of the main assault force in C-130 Hecules. The Air Troop advance team confirmed it was suitable and later that day a fleet of C-130s began to land, each touching down just long enough for the SAS to disembark in their vehicles. Operators from A and G squadron drove directly off the ramps as the planes moved along the desert strip before the aircraft took off again; the squadrons were drove in 38 Land Rover "pinkies", 2 logistics vehicles and 8 Kawasaki dirt bikes, they formed up and proceeded towards their target. One Land Rover broke down due to an engine problem, the vehicle was left behind, its 3-man crew stayed to guard it (they were picked when the assault force exfilled). The assault force drove to a previously agreed forming-up point and split into two elements - the main assault force and the FSB (fire support base), A Squadron was given the task of assaulting the target facility, whilst G Squadron took the role of FSB, G Squadron would suppress the enemy with vehicle-mounted GPMGs, .50cal HMGs, MILAN antitank missiles along with 81mm mortars and M82A1 sniper rifle, allowing A squadron closed in on the target (the force was out of range of the Coalition artillery guns).[170]

The Assault began with a preparatory airstrike, following this, A Squadron moved from its start line, firing its weapon; they pulled up meters from the outer perimeter to dismount from their vehicles and closed in on the target on foot. All the while, G Squadron provided covering fire with heavy weapons onto the facility. Air support flew sorties until they ran out of munitions; on a final pass, a US Navy F-18 Hornet strafed a bunker with its 20mm cannon, which narrowly missed several members of G Squadron.[171] As A Squadron closed on the fortified positions several SAS troopers were wounded, the al-Qaeda fighters were not particularly well trained but they were fanatical fighters and most relished the fight. The SAS had to fight hard for every inch of progress.[172] The RSM in command of the FSB joined in the action, he brought forward teams to reinforce A Squadron when he believed the assault was stalling, they were several hundred meters from the enemy positions when he was shot in the leg by an AK-47 round.[171] Eventually, the A Squadron assault force reached the objective, they cleared the HQ building, gathering all intelligence materials they could find.[172] The mission lasted 4 hours and a total of 4 SAS operators were wounded; the operation became the largest British SAS operation in history.[173]

Battle of Qala-i-Jangi

On November 25, as Taliban and terrorist prisoners were moved into Qala-I-Janghi fortress near Mazar-I-Sharif, a few Taliban attacked their Northern Alliance guards. This incident triggered a revolt by 600 prisoners, who soon seized the southern half of the medieval fortress, including an armory stocked with an array of AK47s, RPGs and crew-served weapons. Johnny Micheal Spann, one of two CIA SAD operatives at the fortress who had been interrogating prisoners, was killed, marking America's first combat death.[174]

The other CIA operator, known as 'Dave,' managed to make contact with CENTCOM who relayed his request for assistance to SOF troops at TF Dagger safe house in Mazar-e-Sharif. The safe house housed members of Delta Force, some Green Berets and a small team from M squadron SBS. A QRF was immediately formed of whoever was in the safe house at the time: a headquarters element from 3rd Battalion, 5th SFG, a pair of USAF liaison officers, a handful of CIA SAD operators and the SBS team. The 8-man SBS team arrived in Land Rover 90s and the Green Berets and CIA operatives arrived in minivans and began engaging the prisoners, fighting a pitched battle to "stem the tide" of the uprising; as a result, CIA operative 'Dave' managed to escape, following this the operators turned their attention to recovering Spann's body. Over the course of 4 days the battle continued, Green Berets called in multiple airstrikes on the Taliban prisoners, during one CAS mission a JDAM was misdirected and hit the ground close to the Coalition and Northern Alliance positions, wounding 5 Green Berets and four SBS operators to various degrees.[175]

AC-130 gunships kept up aerial bombardments throughout the night, the following day (November 27) the siege was finally broken as Northern Alliance T-55 tanks were brought into the central courtyard to fire shells from its main guns into several block houses containing Taliban. Fighting continued sporadically thought the week as the last remnants were mopped out by Dostrum's Northern Alliance forces, the combined Green Beret-SBS team recovered Spann's body.[176]

The revolt was crushed after seven days of fighting involving a Special Boat Service unit, Army Special Forces, and Northern Alliance forces and other aircraft provided strafing fire and launched bombs.[177] 86 Taliban survived, and around 50 Northern Alliance soldiers were killed. The revolt was the final combat in northern Afghanistan.

Consolidation: the taking of Kandahar

ODA 574 and Hamid Karzai began moving on Kandahar, gathering fighters from friendly local Pashtun tribes. His militia force eventually numbered some 800 men. They fought for two days with the Taliban, who were dug into ridge-lines overlooking the strategic Sayd-Aum-Kalay Bridge, eventually seizing it, with the help of US air-power, and opening the road to Kandahar.[178]

By the end of November, Kandahar was the Taliban's last stronghold, and was coming under increasing pressure. Nearly 3,000 tribal fighters, led by Karzai and Gul Agha Sherzai, the governor of Kandahar before the Taliban seized power, pressured Taliban forces from the east and cut off northern supply lines to Kandahar. The Northern Alliance loomed in the north and northeast.

ODA 583 had infiltrated the Shin-Narai Valley, southeast of Kandahar to support Gul Agha Sherzai, the former governor of Kandahar. By November 24, ODA 583 had established covert observations posts, which allowed them to call in devastating fire on Taliban positions.[179]

Meanwhile, nearly 1,000 US Marines, ferried in by CH-53E Super Stallion helicopters and C-130s, set up a Forward Operating Base known as Camp Rhino in the desert south of Kandahar on November 25. This was the coalition's first base, and enabled other operating bases to form. The first significant combat involving US ground forces occurred a day after Rhino was captured, when 15 Taliban armored vehicles approached the base and were attacked by helicopter gunships, destroying many of them. Meanwhile, airstrikes continued to pound Taliban positions inside the city, where Mullah Omar remained. Omar remained defiant although his movement controlled only four out of 30 Afghan provinces by the end of November. He called on his forces to fight to the death.

On December 5, a 2,000 lb GPS-guided bomb landed among the Green Berets from ODA 574, killing 3 members and wounding the rest of the team. Over 20 of Karzai's militia were also killed and Karzai himself slightly wounded. A Delta Force unit nearby that had been operating nearby on a classified reconnaissance mission arrived in their Pinzgauers and secured the site, while Delta medics worked with wounded Green Berets. Along with a USMC CH-53 casualty evacuation helicopter onboard ODB 570 and ODA 524 were immediately dispatched by helicopter to assist with the wounded and to eventually replace the fallen operators of ODA 574.[178]

On December 6, Karzai was informed that he would be the next president of Afghanistan, he also negotiated the successful surrender of both the remaining Taliban forces around Sayd-Aum-Kalay and the entire city of Kandahar itself. ODA 524, ODB 570 and Karzai's militia began their final push to clear the city.[179] The US government rejected amnesty for Omar or any Taliban leaders. On December 7, Sherzai's forces seized Kandahar airport and moved in the city of Kandahar.[179] Omar slipped out of Kandahar with a group of loyalists and moved northwest into the mountains of Uruzgan Province, thus reneging on the Taliban's promise to surrender their fighters and their weapons. He was last reported seen leaving in a convoy of motorcycles.

Other Taliban leaders fled to Pakistan through the remote passes of Paktia and Paktika Provinces. The border town of Spin Boldak surrendered on the same day, marking the end of Taliban control in Afghanistan. Afghan forces under Gul Agha seized Kandahar, while the US Marines took control of the airport and established a US base.

Also in early December 2001, as the US invasion of Afghanistan was almost completed, it was reported that warlord Dostum's forces, who were fighting the Taliban alongside the US Special Forces, had intentionally suffocated as many as 3,000 Taliban prisoners in container trucks in an incident that has become known as the Dasht-i-Leili massacre.[180][181][182][183][184][185][186] The Taliban prisoners were shot and/or suffocated while being transferred by US and Junbish-i Milli soldiers from Kunduz to Sheberghan prison in Afghanistan. The site of the graves is believed to be in the Dasht-i-Leili desert just west of Sheberghan, in the Jowzjan Province.

Battle of Tora Bora

After the fall of Kabul and Kandahar, al-Qaeda elements including Bin Laden and other key leaders withdrew to Jalalabad, Nangarhar Province, from there they moved into the Tora Bora region of the White Mountains, 20 km away from the Pakistan border - where there was a network of caves and prepared defenses used by the mujahideen during the Soviet-Afghan War. Signal intercepts and interrogation of captured Taliban fighters and al-Qaeda terrorists pointed towards the presence of significant numbers of foreign fighters and possible HVTs in and moving to the area; instead of committing conventional forces, higher echelons of both the White House and the Pentagon took the decision to isolate and destroy the al-Qaeda elements in the area with the US SOF supporting locally recruited AMFs (Afghan Militia Forces) - due to misplaced fear of replicating the Soviets experience in the area.[187]

ODA 572 and a CIA Jawbreaker team (small group of CIA SAD ground branch operators) were dispatched to Tora Bora to advise eastern anti-Taliban forces under the command of two warlords: Hazrat Ali and Mohammed Zaman (both had a deep-seated distrust toward each other); using CIA hard currency, some 2,500 to 3,000 AMF were recruited for the coming battle; al-Qaeda were using Tora Bora as a final strongpoint. The leader of the CIA Jawbreaker team requested a battalion of Rangers - 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment - to be dropped into the mountains to establish blocking positions along potential escape routes out of Tora Bora into Pakistan. They would serve as the 'anvil' whilst Green Berets with the AMF would be the 'Hammer,' with attached Air Force Combat Controllers, the Rangers could direct airstrikes onto enemy concentrations or engage them in ambushes; troops from the 10th Mountain Division were also an option, but this was denied.[188]

From the outset of the battle, ODA 572 with its attached Combat Controller called in precision airstrikes (15,000lb Daisy Cutters were often used), whilst their AMFs launched what amounted to a number of poorly executed and coordinated attacks on established al-Qaeda positions with a predictable degree of success. The Green Berets discovered that the militias lacked both the motivation and skill for the battle: according to ODA members they would gain ground in the morning following US airstrikes and then relinquish control of those gains the same day, they would also retreat to their base areas for sleep each night. With the AMF offensive stalled and the CIA and ODA teams overstretched, the decision was made to deploy more troops into the battle.[189]

40 operators from A squadron Delta Force were forward deployed to Tora Bora and would assume tactical command of the battle from the CIA, with the Delta squadron were a dozen of so members of M squadron SBS, members of MI6 also deployed to the region alongside the SBS. The Delta operators were deployed in small teams embedded within the militias and sent their own Recce operators out to pick up Bin Laden's trail, eventually with the assistance of Green Berets and CIA operators cajoling the AMF, progress was made. The Delta squadron commander agreed with the Jawbreaker assessment of the situation and requested blocking forces or the scattering of aerial landmines to deny mountain passes to the enemy and since the deployment of the Ranger battalion had been denied, he requested that his operators carryout their proposed role but all his requests were denied by General Franks. On December 12, two weeks into the battle, AMF commander Zaman opened negotiations with the trapped al-Qaeda and Taliban in Tora Bora, despite the frustrations of the Americans and British, a temporary truce was called until 0800hr the following morning to allow al-Qaeda to supposedly agree to surrender terms by Shura (group meeting). This was a ruse played to allow as many as several hundred al-Qaeda and members of the 055 Brigade to escape over night toward Pakistan.[190][191]

The following day, a handheld ICOM radio recovered from the body of a dead al-Qaeda fighter allowed members of the Delta squadron, SBS, CIA, and MI6 to hear Bin laden's voice - apparently apologizing to his followers for leading them to Tora Bora and giving his blessing for their surrender - thought to be addressed to the terrorists that stayed to fight a rearguard action to allow Bin Laden to escape. Credible rumors of cash payments by Bin Laden to at least one of the warlords abound - the reluctance of the AMF to press the attack may have been influenced by similar bribes. The leader of the CIA Jawbreaker team at Tora Bora believed that two large al-Qaeda groups escaped: the smaller group of 130 jihadis escaped east into Pakistan, while the second group including Bin Laden and 200 Saudi and Yemeni jihadis took the route across the mountains to the town of Parachinar, Pakistan; the Delta squadron commander believed that Bin Laden crossed the border into Pakistan sometime around December 16. A Delta Recce team, call-sign 'Jackal', spotted a tall man wearing a camouflage jacket with a large number of fighters entering a cave, the Recce team called in multiple airstrikes on the obvious presumption that it was Bin Laden, but later DNA analysis from the remains did not match Bin Laden's. With the majority of the terrorists gone the battle came to an end, official tallies of claiming hundreds of al-Qaeda killed at Tora Bora are difficult to confirm since many of the bodies were buried in caves or vaporized by bombs, just under 60 prisoners were taken.[192][191][193] Around December 17, across the border, Pakistani Border Scouts, allegedly assisted by members of JSOC and the CIA in capturing an upward of another 300 foreign fighters.

On December 20, ODA 561 were inserted into the White Mountains to support ODA 572 in conducting SSE of the caves and to assist with recovering DNA samples from terrorist bodies.[194]

US and UK forces continued searching into January, but no sign of al-Qaeda leadership emerged. An estimated 200 al-Qaeda fighters were killed during the battle, along with an unknown number of tribal fighters. No American or British deaths were reported.

Diplomatic and humanitarian efforts

In December 2001 the United Nations hosted the Bonn Conference. The Taliban were excluded. Four Afghan opposition groups participated. Observers included representatives of neighboring and other involved major countries.

The resulting Bonn Agreement created the Afghan Interim Authority that would serve as the "repository of Afghan sovereignty" and outlined the so-called Petersberg Process that would lead towards a new constitution and a new Afghan government.

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1378 of November 14, 2001, included "Condemning the Taliban for allowing Afghanistan to be used as a base for the export of terrorism by the al-Qaeda network and other terrorist groups and for providing safe haven to Osama bin Laden, al-Qaeda and others associated with them, and in this context supporting the efforts of the Afghan people to replace the Taliban regime".[195]

The United Nations World Food Programme temporarily suspended activities within Afghanistan at the beginning of the bombing attacks but resumed them after the fall of the Taliban.

Security force for Kabul

On December 20, 2001, the United Nations authorized an International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), with a mandate to help the Afghans maintain security in Kabul and surrounding areas. It was initially established from the headquarters of the British 3rd Mechanised Division under Major General John McColl, and for its first years numbered no more that 5,000.[196] The force had the invitation of the new interim Afghan government;[197] Its mandate did not extend beyond the Kabul area for the first few years.[198] Eighteen countries were contributing to the force in February 2002.

2002: Operation Anaconda

In January 2002, another series of caves was discovered in Zawar Kili, just south of Tora Bora, airstrikes hit the sites before SOF teams were inserted into the area. A SEAL platoon from SEAL Team 3, including several of their Desert Patrol Vehicles, accompanied by a German KSK element, a Norwegian SOF team and JTF2 reconnaissance teams spent some nine days conducting extensive searches/site exploitation, clearing an estimated 70 caves and 60 structures in the area, recovering a huge amount of both intelligence and munitions, but they didn't encounter any al-Qaeda fighters.[199]

Following the Loya jirga, tribal leaders and former exiles established an interim government in Kabul under Hamid Karzai. US forces established their main base at Bagram airbase just north of Kabul. Kandahar airport also became an important US base. Outposts were established in eastern provinces to hunt for Taliban and al-Qaeda fugitives.

Al-Qaeda forces regrouped in the Shah-i-Kot Valley area, Paktia province, in January and February 2002. A Taliban fugitive in Paktia province, Mullah Saifur Rehman began reconstituting some of his militia forces. They totaled over 1,000 by the beginning of March 2002. The insurgents wanted to launch guerrilla attacks and possibly a major offensive, copying 1980s anti-Soviet fighters.

The US detected the buildup, and on March 2, 2002, US, Canadian, and Afghan forces began "Operation Anaconda" against them. The trucks of Task Force Hammer become stuck in the mud while owing to a communications mistake, the massive aerial bombardment did not take place.[200] The poorly trained Afghan government troops proved incapable of fighting al-Qaeda without air support.[200] Mujahideen forces, using small arms, rocket-propelled grenades, and mortars, were entrenched into caves and bunkers in the hillsides largely above 3,000 m (10,000 ft). They used "hit and run" tactics, opening fire and then retreating to their caves and bunkers to weather the return fire and bombing. US commanders initially estimated their opponents as an isolated pocket numbering fewer than 200. Instead the guerrillas numbered between 1,000–5,000, according to some estimates.[201] By March 6, eight American, seven Afghan allied, and up to 400 Al Qaida opposing fighters had been killed.[202] At one point, while coming under heavy al-Qaeda force, the Afghan government forces fled in panic and refused to fight, leading to the men of Task Force Hammer to take on al-Qaeda alone.[203] "Friendly fire" incidents where American troops were bombed by their air force several times added to further difficulties.[203] Sub-engagements included the Battle of Takur Ghar on 'Roberts Ridge,' and follow-up Operations Glock and Polar Harpoon.[204]