هجوم تيت

| هجوم تـِت Tet Offensive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جزء من حرب ڤيتنام | |||||||

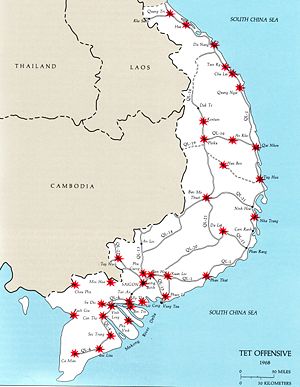

خريطة تبين البلدات والمدن التي دار فيها قتال رئيسي أثناء هجوم تت 1968 | |||||||

| |||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| القوى | |||||||

| ~1.3 مليون[5] |

المرحلة 1: ~80,000 الإجمالي: ~323,000 – 595,000[6] | ||||||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||||||

|

المرحلة الأولى: 1.536 قتيل، 7.764 جريح، 11 فقيد المرحلة الثانية: 1,161 قتيل، 3.954 جريح المرحلة الثالثة: 700 قتيل وجريح مجهول الهوية إجمالي جيوش الحلفاء: 6.328 قتيل (تقريبي)، 20.663 جريح (تقريبي)، 1.185 فقيد[7] |

في المرحلة الأولى: أحد مصادر PAVN (سايگون فقط):

المرحلة الأولى، المرحلة الثانية والمرحلة الثالثة: | ||||||

| المدنيون: 14,300 قتيل، 24,000 جريح، و 630,000 refugees[14] | |||||||

هجوم تيت[15]، كان تصعيدًا كبيرًا وواحداً من أكبر الحملات العسكرية في حرب ڤيتنام. شنت ڤيت كونگ (VC) وجيش ڤيتنام الشعبي (PAVN) الڤيتنامي الشمالي هجومًا خاطفًا في 30 يناير 1968، ضد جيش جمهورية ڤيتنام (ARVN) الڤيتنامي الجنوبي، والقوات المسلحة الأمريكية وحلفائهم. كانت حملة من الهجمات المفاجئة ضد مراكز القيادة والسيطرة العسكرية والمدنية في جميع أنحاء ڤيتنام الجنوبية.[16] الاسم هو نسخة مبتورة من اسم مهرجان السنة القمرية الجديدة باللغة الڤيتنامية، تيت وين دان، مع اختيار وقت الهجوم خلال فترة العطلة حيث كان معظم أفراد جيش جمهورية ڤيتنام في إجازة.[17] كان الغرض من الهجوم واسع النطاق الذي شنه المكتب السياسي لهانوي هو إثارة الفوضى السياسية، اعتقادًا بأن الهجوم المسلح الجماعي على المراكز الحضرية من شأنه أن يؤدي إلى حدوث انشقاقات وتمردات.

شُن الهجوم في ساعات مبكرة يوم 30 يناير في أجزاء كبيرة من المناطق التكتيكية للفيلق الأول والثاني في ڤيتنام الجنوبية. أتاح هذا الهجوم المبكر لقوات الحلفاء بعض الوقت لإعداد التدابير الدفاعية. عندما بدأت العملية الرئيسية خلال ساعات الصباح الباكر من يوم 31 يناير، كان الهجوم يشمل جميع أنحاء البلاد؛ في النهاية، قام أكثر من 80.000 من قوات PAVN/VC بضرب أكثر من 100 بلدة ومدينة، بما في ذلك 36 من 44 عاصمة إقليمية، وخمس من المدن الستة ذاتية الحكم، و72 من 245 بلدة، والعاصمة الجنوبية.[18] كان الهجوم أكبر عملية عسكرية قام بها أي من الجانبين حتى تلك اللحظة من الحرب.

شنت هانوي الهجوم معتقدة أنه سيؤدي إلى انتفاضة شعبية تؤدي إلى انهيار حكومة ڤيتنام الجنوبية. على الرغم من أن الهجمات الأولية فاجأت الحلفاء، مما أدى إلى فقدانهم السيطرة على عدة مدن مؤقتًا، إلا أنهم سرعان ما أعادوا تجميع صفوفهم وصدوا الهجمات وألحقوا خسائر فادحة بقوات PAVN / VC. الانتفاضة الشعبية التي توقعتها هانوي لم تحدث قط. أثناء معركة هوي، استمر القتال العنيف لمدة شهر، مما أدى إلى تدمير المدينة. أثناء احتلالهم، أعدمت PAVN/VC آلاف الأشخاص في مذبحة هوي. حول القاعدة القتالية الأمريكية في كي سانه، استمر القتال لمدة شهرين آخرين.

كان الهجوم بمثابة هزيمة عسكرية لڤيتنام الشمالية، حيث لم تحدث انتفاضات ولا انشقاقات في وحدة جيش جمهورية ڤيتنام الجنوبية. ومع ذلك، كان لهذا الهجوم عواقب بعيدة المدى بسبب تأثيره على آراء الجمهور الأمريكي والعالم على نطاق واسع حول حرب فيتنام. أفاد الجنرال ويستمورلاند أن هزيمة PAVN/VC ستتطلب 200.000 جندي أمريكي إضافي وتفعيل الاحتياطيات، مما دفع حتى المؤيدين المخلصين للحرب إلى رؤية أن استراتيجية الحرب الحالية تتطلب إعادة التقييم.[19] لاحقاً، سعت إدارة جونسون إلى مفاوضات لإنهاء الحرب. قبل وقت قصير من الانتخابات الرئاسية الأمريكية 1968، شجع المرشح الجمهوري، نائب الرئيس السابق رتشارد نكسون، رئيس ڤيتنام الجنوبية وين ڤان ثيو أن يكون غير متعاون علنًا مع المفاوضات، مما يوضح أنه من غير المرجح أن ينجح جونسون في صنع السلام في أي وقت قريب.[20]

يشير مصطلح "هجوم تيت" عادةً إلى هجوم يناير-فبراير 1968، لكنه يمكن أن يشمل أيضاً ما يسمى بهجوم "ميني-تت" الذي وقع في مايو وهجوم المرحلة الثالثة في أغسطس، أو 21 أسبوعاً من القتال العنيف غير المعتاد الذي أعقب الهجمات الأولية في يناير.[21]

خلفية

السياق السياسي بڤيتنام الجنوبية

Leading up to the Tet Offensive were years of marked political instability and a series of coups after the 1963 South Vietnamese coup. In 1966, the leadership in South Vietnam, represented by the Head of State Nguyễn Văn Thiệu and Prime Minister Nguyễn Cao Kỳ were persuaded to commit to democratic reforms in an effort to stabilize the political situation at a conference in Honolulu. Prior to 1967, the South Vietnamese constituent assembly was in the process of drafting a new constitution and eventual elections.[22] The political situation in South Vietnam, after the 1967 South Vietnamese presidential election, looked increasingly stable. Rivalries between South Vietnam's generals were becoming less chaotic, and Thiệu and Kỳ formed a joint ticket for the election. Despite efforts by North Vietnam to disrupt elections, higher than usual turnouts saw a political turning point towards a more democratic structure and ushered in a period of political stability after a series of coups had characterized the preceding years.[23]

Protests, campaigning and the atmosphere of elections had been interpreted by the Politburo of the Communist Party of Vietnam and Lê Duẩn as signs that the population would embrace a 'general uprising' against the government of South Vietnam. The Politburo sought to exploit perceived instability and maintain political weakness in South Vietnam.[24]

استراتيجية الحرب للولايات المتحدة

During late 1967, the question whether the U.S. strategy of attrition was working in South Vietnam weighed heavily on the minds of the American public and the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson. General William C. Westmoreland, the commander of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), believed that if a "crossover point" could be reached by which the number of communist troops killed or captured during military operations exceeded those recruited or replaced, the Americans would win the war. There was a discrepancy, however, between the order of battle estimates of the MACV and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) concerning the strength of VC guerrilla forces within South Vietnam.[25] In September, members of the MACV intelligence services and the CIA met to prepare a Special National Intelligence Estimate that would be used by the administration to gauge U.S. success in the conflict.

Provided with an enemy intelligence windfall accrued during Operations Cedar Falls and Junction City, the CIA members of the group believed that the number of VC guerrillas, irregulars, and cadre within the South could be as high as 430,000. The MACV Combined Intelligence Center, on the other hand, maintained that the number could be no more than 300,000.[26] Westmoreland was deeply concerned about the possible perceptions of the American public to such an increased estimate since communist troop strength was routinely provided to reporters during press briefings.[27] According to MACV's chief of intelligence, General Joseph A. McChristian, the new figures "would create a political bombshell", since they were positive proof that the North Vietnamese "had the capability and the will to continue a protracted war of attrition".[26]

In May, MACV attempted to obtain a compromise from the CIA by maintaining that VC militias did not constitute a fighting force but were essentially low-level fifth columnists used for information collection.[28] The agency responded that such a notion was ridiculous since the militias were directly responsible for half of the casualties inflicted on U.S. forces. With the groups deadlocked, George Carver, CIA deputy director for Vietnamese affairs, was asked to mediate the dispute. In September, Carver devised a compromise: The CIA would drop its insistence on including the irregulars in the final tally of forces and add a prose addendum to the estimate that would explain the agency's position.[29] George Allen, Carver's deputy, laid responsibility for the agency's capitulation at the feet of Richard Helms, the director of the CIA. He believed that "it was a political problem ... [Helms] didn't want the agency ... contravening the policy interest of the administration."[30]

During the second half of 1967 the administration had become alarmed by criticism, both inside and outside the government, and by reports of declining public support for its Vietnam policies.[31] According to public opinion polls, the percentage of Americans who believed that the U.S. had made a mistake by sending troops to Vietnam had risen from 25 percent in 1965 to 45 percent by December 1967.[32] This trend was fueled not by a belief that the struggle was not worthwhile, but by mounting casualty figures, rising taxes, and the feeling that there was no end to the war in sight.[33] A poll taken in November indicated that 55 percent wanted a tougher war policy, exemplified by the public belief that "it was an error for us to have gotten involved in Vietnam in the first place. But now that we're there, let's win – or get out."[34] This prompted the administration to launch a so-called "success offensive", a concerted effort to alter the widespread public perception that the war had reached a stalemate and to convince the American people that the administration's policies were succeeding. Under the leadership of National Security Advisor Walt W. Rostow, the news media then was inundated by a wave of effusive optimism.

Every statistical indicator of progress, from "kill ratios" and "body counts" to village pacification, was fed to the press and to the Congress. "We are beginning to win this struggle", asserted Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey on NBC's Today show in mid-November. "We are on the offensive. The territory is being gained. We are making steady progress."[35] At the end of November, the campaign reached its climax when Johnson summoned Westmoreland and the new U.S. Ambassador, Ellsworth Bunker, to Washington, D.C., for what was billed as a "high-level policy review". Upon their arrival, the two men bolstered the administration's claims of success. From Saigon, pacification chief Robert Komer asserted that the CORDS pacification program in the countryside was succeeding, and that sixty-eight percent of the South Vietnamese population was under the control of Saigon while only seventeen percent was under the control of the VC.[36] General Bruce Palmer Jr., one of Westmoreland's three Field Force commanders, claimed that "the Viet Cong has been defeated" and that "He can't get food and he can't recruit. He has been forced to change his strategy from trying to control the people on the coast to try to survive in the mountains."[37]

Westmoreland was even more emphatic in his assertions. At an address at the National Press Club on 21 November, he reported that, as of the end of 1967, the communists were "unable to mount a major offensive ... I am absolutely certain that whereas in 1965 the enemy was winning, today he is certainly losing...We have reached an important point when the end begins to come into view."[35] By the end of the year the administration's approval rating had indeed crept up by eight percent, but an early January Gallup poll indicated that forty-seven percent of the American public still disapproved of the President's handling of the war.[38] The American public, "more confused than convinced, more doubtful than despairing ... adopted a 'wait and see' attitude."[39] During a discussion with an interviewer from Time magazine, Westmoreland defied the communists to launch an attack: "I hope they try something because we are looking for a fight."[40]

ڤيتنام الشمالية

مناورات حزبية

Planning in Hanoi for a winter-spring offensive during 1968 had begun in early 1967 and continued until early the following year. According to American sources, there has been an extreme reluctance among Vietnamese historians to discuss the decision-making process that led to the general offensive and uprising, even decades after the event.[41] In official Vietnamese literature, the decision to launch the Tet offensive was usually presented as the result of a perceived U.S. failure to win the war quickly, the failure of the American bombing campaign against North Vietnam, and the anti-war sentiment that pervaded the population of the U.S.[42] The decision to launch the general offensive, however, was much more complicated.

هجوم عام وانتفاضة عامة

The operational plan for the general offensive and uprising had its origin as the "COSVN proposal" at Thanh's southern headquarters in April 1967 and had then been relayed to Hanoi the following month. The General was then ordered to the capital to explain his concept in person to the Military Central Commission. At a meeting in July, Thanh briefed the plan to the Politburo.[43] On the evening of 6 July, after receiving permission to begin preparations for the offensive, Thanh attended a party and died of a heart attack after drinking too much. An alternative account is that Thanh died of injuries sustained in a U.S. bombing raid on COSVN after having been evacuated from Cambodia.[44]

عدم استعداد الولايات المتحدة

شكوك ومشتتات

قبل الهجوم

الهجوم

سايجون

هوي

خى سان

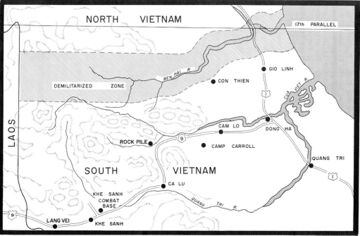

The attack on Khe Sanh, which began on 21 January before the other offensives, probably served two purposes—as a real attempt to seize the position or as a diversion to draw American attention and forces away from the population centers in the lowlands, a deception that was "both plausible and easy to orchestrate."[45] In Westmoreland's view, the purpose of the base was to provoke the North Vietnamese into a focused and prolonged confrontation in a confined geographic area, one which would allow the application of massive U.S. artillery and air strikes that would inflict heavy casualties in a relatively unpopulated region.[46] By the end of 1967, MACV had moved nearly half of its manoeuvre battalions to I Corps in anticipation of just such a battle.

الأعقاب

Except at Huế and mopping-up operations in and around Saigon, the first surge of the offensive was over by the second week of February. The U.S. estimated that during the first phase (30 January – 8 April) approximately 45,000 PAVN/VC soldiers were killed and an unknown number were wounded. For years this figure has been held as excessively optimistic, as it represented more than half the forces involved in this battle. Stanley Karnow claims he confirmed this figure in Hanoi in 1981.[47] Westmoreland himself claimed a smaller number of enemies disabled, estimating that during the same period 32,000 PAVN troops were killed and another 5,800 captured.[48] The South Vietnamese suffered 2,788 killed, 8,299 wounded, and 587 missing in action. U.S. and other allied forces suffered 1,536 killed, 7,764 wounded, and 11 missing.[49]

ڤيتنام الشمالية

The leadership in Hanoi was despondent at the outcome of their offensive.[50][51] Their first and most ambitious goal, producing a general uprising, had ended in a dismal failure. In total, about 85,000–100,000 PAVN/VC troops had participated in the initial onslaught and in the follow-up phases. Overall, during the "Border Battles" of 1967 and the nine-month winter-spring campaign, 45,267 PAVN/VC troops had been killed in action.[52][53]

Hanoi had underestimated the strategic mobility of the allied forces, which allowed them to redeploy at will to threatened areas; their battle plan was too complex and difficult to coordinate, which was amply demonstrated by the 30 January attacks; their violation of the principle of mass, attacking everywhere instead of concentrating their forces on a few specific targets, allowed their forces to be defeated piecemeal; the launching of massed attacks headlong into the teeth of vastly superior firepower; and last, but not least, the incorrect assumptions upon which the entire campaign was based.[54] According to General Tran Van Tra: "We did not correctly evaluate the specific balance of forces between ourselves and the enemy, did not fully realize that the enemy still had considerable capabilities, and that our capabilities were limited, and set requirements that were beyond our actual strength."[55]

The PAVN/VC effort to regain control of the countryside was somewhat more successful. According to the U.S. State Department, the VC "made pacification virtually inoperative. In the Mekong Delta, the Viet Cong was stronger now than ever and in other regions the countryside belongs to the VC."[56] General Wheeler reported that the offensive had brought counterinsurgency programs to a halt and "that to a large extent, the VC now controlled the countryside".[57] This state of affairs did not last; heavy casualties and the backlash of the South Vietnamese and Americans resulted in more territorial losses and heavy casualties.[58][59][60]

The heavy losses inflicted on VC units struck into the heart of the infrastructure that had been built up for over a decade. MACV estimated that 181,149 PAVN/VC troops had been killed during 1968.[61] According to General Tran Van Tra, 45,267 PAVN/VC troops had been killed during 1968.[52] Marilyn B. Young writes:

In Long An province, for example, local guerrillas taking part in the May—June offensive had been divided into several sections. Only 775 out of 2,018 in one section survived; another lost all but 640 out of 1,430. The province itself was subjected to what one historian has called a "My Lai from the Sky" – non-stop B-52 bombing.[62]

From this point forward, Hanoi was forced to fill nearly 70% of the VC's ranks with PAVN regulars.[63] PRG Justice Minister Trương Như Tảng said that the Tet offensive had wiped out half of the VC's strength,[64] while the official Vietnamese war history notes that by 1969, very little communist-held territory ("liberated zones") existed in South Vietnam.[65] Following the Tet offensive and subsequent U.S.–South Vietnamese "search and hold" operations in the countryside throughout the rest of 1968, the VC's recruiting base was more or less wiped out; the official Vietnamese war history later noted that "we could not maintain the level of local recruitment we had maintained in previous years. In 1969 we were only able to recruit 1,700 new soldiers in Region 5 (compared with 8,000 in 1968), and in the lowlands of Cochin China we recruited only 100 new soldiers (compared with 16,000 in 1968)."[66] As also noted by the official history, "because our armed local forces had suffered severe losses, guerrilla operations had declined."[67] However, this change had little effect on the overall result of the war, since in contrast to the VC, the PAVN had little difficulty making up the casualties inflicted by the offensive.[68] Some Western historians have come to believe that one insidious ulterior motive for the campaign was the elimination of competing southern members of the Party, thereby allowing the northerners more control once the war was won.[69]

It was not until after the conclusion of the first phase of the offensive that Hanoi realized that its sacrifices might not have been in vain. General Tran Do, PAVN commander at the battle of Huế, gave some insight into how defeat was translated into victory:

In all honesty, we didn't achieve our main objective, which was to spur uprisings throughout the South. Still, we inflicted heavy casualties on the Americans and their puppets, and this was a big gain for us. As for making an impact in the United States, it had not been our intention—but it turned out to be a fortunate result.[70]

On 5 May Trường Chinh rose to address a congress of Party members and proceeded to castigate the Party militants and their bid for quick victory. His "faction-bashing" tirade sparked a serious debate within the party leadership which lasted for four months. As the leader of the "main force war" and "quick victory" faction, Lê Duẩn also came under severe criticism. In August, Chinh's report on the situation was accepted in toto, published, and broadcast via Radio Hanoi. He had single-handedly shifted the nation's war strategy and restored himself to prominence as the Party's ideological conscience.[71] Meanwhile, the VC proclaimed itself the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam, and took part in future peace negotiations under this title.

The Lê Duẩn faction, which favoured quick, decisive offensives meant to paralyse South Vietnam-United States responses, was replaced by Giáp and Trường Chinh, who favoured a strategy of more protracted, drawn-out conventional warfare.[72] High-intensity, conventional big-unit battles were replaced with smaller-scale, quick attack and quick withdrawal operations to continually put pressure on the allied forces at the same time that mechanised and combined-arms capabilities were being built.[73] The plan for a popular uprising or people's war was abandoned for a greater combination of guerrilla and conventional warfare.[73] During this period, the PAVN would undergo a significant strategic re-structuring, being built into a combined-arms capable force while continually applying pressure on the U.S./ARVN with lighter infantry units. In line with the revamped strategy of Hanoi, on April 5, 1969, COSVN issued Directive 55 to all of its subordinate units: "Never again and under no circumstances are we going to risk our entire military force for just such an offensive. On the contrary, we should endeavor to preserve our military potential for future campaigns."[74]

The PAVN official history describes the first phase of the Tet offensive as a "great strategic victory" that "killed or dispersed 150,000 enemy soldiers including 43,000 Americans, destroyed 34 percent of the American war reserve supplies in Vietnam, destroyed 4,200 strategic hamlets and liberated an additional 1.4 million people."[75]

ڤيتنام الجنوبية

South Vietnam was a nation in turmoil both during and in the aftermath of the offensive. Tragedy had compounded tragedy as the conflict reached into the nation's cities for the first time. As government troops pulled back to defend the urban areas, the VC moved in to fill the vacuum in the countryside. The violence and destruction witnessed during the offensive left a deep psychological scar on the South Vietnamese civilian population. Confidence in the government was shaken, since the offensive seemed to reveal that even with massive American support, the government could not protect its citizens.[76]

A political rivalry had also re-emerged after the 1967 South Vietnamese presidential election, when the coalition between Nguyễn Văn Thiệu and Air Force commander Nguyễn Cao Kỳ re-emerged. Kỳ would be sidelined by Thiệu for the duration of the war afterwards, retaining his position as Vice President.[23]

The human and material cost to South Vietnam was staggering. The number of civilian dead was estimated by the government at 14,300 with an additional 24,000 wounded.[14] 630,000 new refugees had been generated, joining the nearly 800,000 others already displaced by the war. By the end of 1968, one of every twelve South Vietnamese was living in a refugee camp.[14] More than 70,000 homes had been destroyed in the fighting and perhaps 30,000 more were heavily damaged and the nation's infrastructure had been virtually destroyed. The South Vietnamese military, although it had performed better than the Americans had expected, suffered from lowered morale, with desertion rates rising from 10.5 per thousand before Tet to 16.5 per thousand by July.[77] 1968 became the deadliest year of the war to date for the ARVN with 27,915 men killed.[61]

In the wake of the offensive, however, fresh determination was exhibited by the Thiệu government. On 1 February Thiệu declared a state of martial law, and on 15 June, the National Assembly passed his request for a general mobilization of the population and the induction of 200,000 draftees into the armed forces by the end of the year (a decree that had failed to pass only five months previously due to strong political opposition).[78] This increase would bring South Vietnam's troop strength to more than 900,000 men.[79][80] Military mobilization, anti-corruption campaigns, demonstrations of political unity, and administrative reforms were quickly carried out.[81] Thiệu also established a National Recovery Committee to oversee food distribution, resettlement, and housing construction for the new refugees. Both the government and the Americans were encouraged by a new determination that was exhibited among the ordinary citizens of South Vietnam. Many urban dwellers were indignant that the communists had launched their attacks during Tet, and it drove many who had been previously apathetic into active support of the government. Journalists, political figures, and religious leaders alike—even the militant Buddhists—professed confidence in the government's plans.[82]

Thiệu saw an opportunity to consolidate his personal power and he took it. His only real political rival was Vice President Kỳ, the former Air Force commander, who had been outmaneuvered by Thiệu in the presidential election of 1967. In the aftermath of Tet, Kỳ supporters in the military and the administration were quickly removed from power, arrested, or exiled.[83] A crack-down on the South Vietnamese press also ensued and there was a worrisome return of former President Ngô Đình Diệm's Cần Lao Party members to high positions in the government and military. By the summer of 1968, the President had earned a less exalted sobriquet among the South Vietnamese population, who had begun to call him "the little dictator."[84]

Thiệu had also become very suspicious of his American allies, unwilling to believe (as did many South Vietnamese) that the U.S. had been caught by surprise by the offensive. "Now that it's all over", he queried a visiting Washington official, "you really knew it was coming, didn't you?"[85][86] Lyndon Johnson's unilateral decision on 31 March to curtail the bombing of North Vietnam only confirmed what Thiệu already feared, that the Americans were going to abandon South Vietnam to the communists. For Thiệu, the bombing halt and the beginning of negotiations with the North brought not the hope of an end to the war, but "an abiding fear of peace."[85] He was only mollified after an 18 July meeting with Johnson in Honolulu, where Johnson affirmed that Saigon would be a full partner in all negotiations and that the U.S. would not "support the imposition of a coalition government, or any other form of government, on the people of South Vietnam."[87]

الولايات المتحدة

The Tet Offensive created a crisis within the Johnson administration, which became increasingly unable to convince the American public that it had been a major defeat for the communists. The optimistic assessments made before the offensive by the administration and the Pentagon came under heavy criticism and ridicule as the "credibility gap" that had opened in 1967 widened into a chasm.[88]

At the time of the Tet Offensive, the majority of the American public perceived that the war was not being won by the United States and its allies, despite assurances from the President and military leaders that such was the case.[89] No matter that the PAVN/VC lost about 30,000 of their best troops in the fighting at Tet, they were capable of replacing those lost with recruits from North Vietnam.[90] In 1969, the year after the Tet battles, the US suffered 11,780 killed, the second highest annual total in the war.[91] This was a clear indication that the North Vietnamese were capable of ongoing offensive actions, despite their losses at Tet. Most Americans were tired of suffering so many casualties without evidence that they were going to stop anytime in the foreseeable future.[92] Walter Cronkite, anchorman of the CBS Evening News, argued for negotiations as an honourable way out in a Special Report based on his journalism in Vietnam broadcast on CBS TV in March.[93][94]

The shocks that reverberated from the battlefield continued to widen: On 18 February 1968 MACV posted the highest U.S. casualty figures for a single week during the entire war: 543 killed and 2,547 wounded.[95] As a result of the heavy fighting, 1968 went on to become the deadliest year of the war for the US forces with 16,592 soldiers killed.[96] On 23 February the U.S. Selective Service System announced a new draft call for 48,000 men, the second highest of the war.[97] On 28 February Robert S. McNamara, the Secretary of Defense who had overseen the escalation of the war in 1964–1965, but who had eventually turned against it, stepped down from office.[98]

طلب قوات اضافية

During the first two weeks of February, Generals Westmoreland and Wheeler communicated as to the necessity for reinforcements or troop increases in Vietnam. Westmoreland insisted that he only needed those forces either in-country or already scheduled for deployment and he was puzzled by the sense of unwarranted urgency in Wheeler's queries.[99] Westmoreland was tempted, however, when Wheeler emphasized that the White House might loosen restraints and allow operations in Laos, Cambodia, or possibly even North Vietnam itself.[100] On 8 February, Westmoreland responded that he could use another division "if operations in Laos are authorized".[101] Wheeler responded by challenging Westmoreland's assessment of the situation, pointing out dangers that his on-the-spot commander did not consider palpable, concluding: "In summary, if you need more troops, ask for them."[102]

Wheeler's promptings were influenced by the severe strain imposed upon the U.S. military by the Vietnam commitment, which had been undertaken without mobilising its reserve forces. The Joint Chiefs had repeatedly requested national mobilization, not only to prepare for a possible intensification of the war but also to ensure that the nation's strategic reserve did not become depleted.[103] By obliquely ordering Westmoreland to demand more forces, Wheeler was attempting to solve two pressing problems.[104] In comparison with MACV's previous communications, which had been full of confidence, optimism, and resolve, Westmoreland's 12 February request for 10,500 troops was much more urgent: "which I desperately need ... time is of the essence".[105] On 13 February, 10,500 previously authorized U.S. airborne troops and marines were dispatched to South Vietnam. The Joint Chiefs then played their hand, advising President Johnson to turn down MACV's requested division-sized reinforcement unless he called up some 1,234,001 marine and army reservists.[106]

Johnson dispatched Wheeler to Saigon on 20 February to determine military requirements in response to the offensive. Both Wheeler and Westmoreland were elated that McNamara would be replaced by the hawkish Clark Clifford in only eight days and that the military might finally obtain permission to widen the war.[107] Wheeler's written report of the trip, however, contained no mention of any new contingencies, strategies, or the building up of the strategic reserve. It was couched in grave language that suggested that the 206,756-man request it proposed was a matter of vital military necessity.[108] Westmoreland wrote in his memoir that Wheeler had deliberately concealed the truth of the matter to force the issue of the strategic reserve upon the President.[109]

On 27 February, Johnson and McNamara discussed the proposed troop increase. To fulfil it would require an increase in the overall military strength of about 400,000 men and the expenditure of an additional $10 billion during fiscal 1969 and another $15 billion in 1970.[110] These monetary concerns were pressing. Throughout the fall of 1967 and the spring of 1968, the U.S. was struggling with "one of the most severe monetary crises" of the period. Without a new tax bill and budgetary cuts, the nation would face even higher inflation "and the possible collapse of the monetary system".[111] Johnson's friend Clifford was concerned about what the American public would think of the escalation: "How do we avoid creating the feeling that we are pounding troops down a rathole?"[112]

According to the Pentagon Papers, "A fork in the road had been reached and the alternatives stood out in stark reality."[113] To meet Wheeler's request would mean a total U.S. military commitment to South Vietnam. "To deny it, or to attempt to cut it to a size which could be sustained by the thinly stretched active forces, would just as surely signify that an upper limit to the U.S. military commitment in South Vietnam had been reached."[113]

إعادة تقييم

To evaluate Westmoreland's request and its possible impact on domestic politics, Johnson convened the "Clifford Group" on 28 February and tasked its members with a complete policy reassessment.[114] Some of the members argued that the offensive represented an opportunity to defeat the North Vietnamese on American terms while others pointed out that neither side could win militarily, that North Vietnam could match any troop increase, that the bombing of the North is halted, and that a change in strategy was required that would seek not victory, but the staying power required to reach a negotiated settlement. This would require a less aggressive strategy that was designed to protect the population of South Vietnam.[115] The divided group's final report, issued on 4 March, "failed to seize the opportunity to change directions... and seemed to recommend that we continue rather haltingly down the same road."[116]

On 1 March, Clifford succeeded McNamara as Secretary of Defense. During the month, Clifford, who had entered office as a staunch supporter of the Vietnam commitment and who had opposed McNamara's de-escalatory views, turned against the war. According to Clifford: "The simple truth was that the military failed to sustain a respectable argument for their position."[117] Between the results of Tet and the meetings of the group that bore his name, he became convinced that deescalation was the only solution for the United States. He believed that the troop increase would lead only to a more violent stalemate and sought out others in the administration to assist him in convincing the President to reverse the escalation, cap force levels at 550,000 men, seek negotiations with Hanoi, and turn responsibility for the fighting over to the South Vietnamese.[118] Clifford quietly sought allies and was assisted in his effort by the so-called "8:30 Group" – Nitze, Warnke, Phil G. Goulding (Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs), George Elsey and Air Force Colonel Robert E. Pursely.

On 27 February, Secretary of State Dean Rusk proposed that a partial bombing halt be implemented in North Vietnam and that an offer to negotiate be extended to Hanoi.[119] On 4 March, Rusk reiterated the proposal, explaining that, during the rainy season in the North, the bombing was less effective and that no military sacrifice would thus occur. This was purely a political ploy, however, since the North Vietnamese would probably again refuse to negotiate, casting the onus on them and "thus freeing our hand after a short period...putting the monkey firmly upon Hanoi's back for what was to follow."[120][121]

While this was being deliberated, the troop request was leaked to the press and published in The New York Times on 10 March.[122] The article also revealed that the request had begun a serious debate within the administration. According to it, many high-level officials believed that the U.S. troop increase would be matched by the communists and would simply maintain a stalemate at a higher level of violence. It went on to state that officials were saying in private that "widespread and deep changes in attitudes, a sense that a watershed has been reached."[123]

A great deal has been said by historians concerning how the news media made Tet the "turning point" in the public's perception of the war. Popular CBS anchor Walter Cronkite stated during a news broadcast on February 27, "We have been too often disappointed by the optimism of the American leaders, both in Vietnam and Washington, to have faith any longer in the silver linings they find in the darkest clouds" and added that, "we are mired in a stalemate that could only be ended by negotiation, not victory."[124] Far from suffering a loss of morale, however, the majority of Americans had rallied to the side of the president. A Gallup poll in January 1968 revealed that 56 per cent polled considered themselves hawks on the war and 27 per cent doves, with 17 per cent offering no opinion.[125] By early February, at the height of the offensive's first phase, 61 per cent declared themselves hawks, 23 per cent doves, and 16 per cent held no opinion. Johnson, however, made few comments to the press during or immediately after the offensive, leaving an impression of indecision on the public. It was this lack of communication that caused a rising disapproval rating for his conduct in the war. By the end of February, his approval rating had fallen from 63 per cent to 47 per cent. By the end of March, the percentage of Americans that expressed confidence in U.S. military policies in Southeast Asia had fallen from 74 to 54 per cent.[126]

By 22 March, President Johnson had informed Kentrell to "forget the 100,000" men.[119] The President and his staff were refining a lesser version of the troop increase – a planned call-up of 62,000 reservists, 13,000 of whom would be sent to Vietnam.[127] Three days later, at Clifford's suggestion, Johnson called a conclave of the "Wise Men".[128] With few exceptions, all of the members of the group had formerly been accounted as hawks on the war. The group was joined by Rusk, Wheeler, Bundy, Rostow, and Clifford. The final assessment of the majority stupefied the group.[129] According to Clifford, "few of them were thinking solely of Vietnam anymore".[130] All but four members called for disengagement from the war, leaving the President "deeply shaken."[131] According to the Pentagon Papers, the advice of the group was decisive in convincing Johnson to reduce the bombing of North Vietnam.[132]

Johnson was depressed and despondent in the course of recent events. The New York Times article had been released just two days before the Democratic Party's New Hampshire primary, where the President suffered an unexpected setback in the election, finishing barely ahead of Senator Eugene McCarthy. Soon afterwards, Senator Robert F. Kennedy announced he would join the contest for the Democratic nomination, further emphasizing the plummeting support for Johnson's administration in the wake of Tet.

The President was to make a televised address to the nation on Vietnam policy on 31 March and was deliberating on both the troop request and his response to the military situation. By 28 March Clifford was working hard to convince him to tone down his hard-line speech, maintaining force levels at their present size, and instituting Rusk's bombing/negotiating proposal. To Clifford's surprise, both Rusk and Rostow (both of whom had previously been opposed to any form of de-escalation) offered no opposition to Clifford's suggestions.[133] On 31 March, President Johnson announced the unilateral (although still partial) bombing halt during his television address. He then stunned the nation by declining to run for a second term in office. To Washington's surprise, on 3 April Hanoi announced that it would conduct negotiations, which were scheduled to begin on 13 May in Paris.

On 9 June, President Johnson replaced Westmoreland as commander of MACV with General Creighton W. Abrams. Although the decision had been made in December 1967 and Westmoreland was made Army Chief of Staff, many saw his relief as punishment for the entire Tet debacle.[134] Abrams' new strategy was quickly demonstrated by the closure of the "strategic" Khe Sanh base and the ending of multi-division "search and destroy" operations. Also gone were discussions of victory over North Vietnam. Abrams' new "One War" policy centred the American effort on the takeover of the fighting by the South Vietnamese (through Vietnamization), the pacification of the countryside, and the destruction of communist logistics.[135] The new administration of President Richard M. Nixon would oversee the withdrawal of U.S. forces and the continuation of negotiations.

المرحلة الثانية

To further enhance their political posture at the Paris talks, which opened on 13 May, the North Vietnamese opened the second phase of the general offensive in late April. U.S. intelligence sources estimated between February and May the North Vietnamese dispatched 50,000 men down the Ho Chi Minh Trail to replace losses incurred during the earlier fighting.[136] Some of the most prolonged and vicious combat of the war opened on 29 April and lasted until 30 May when the 8,000 men of the PAVN 320th Division, backed by artillery from across the DMZ, threatened the U.S. logistical base at Đông Hà, in northwestern Quảng Trị Province. In what became known as the Battle of Dai Do, the PAVN clashed savagely with U.S. Marine, Army and ARVN forces before withdrawing. The PAVN lost an estimated 2,100 men according to US/ARVN claims, after inflicting casualties on the allies of 290 killed and 946 wounded.[137][138]

During the early morning hours of 4 May, PAVN/VC units initiated the second phase of the offensive (known by the South Vietnamese and Americans as "Mini-Tet") by striking 119 targets throughout South Vietnam, including Saigon. This time, however, allied intelligence was better prepared, stripping away the element of surprise. Most of the communist forces were intercepted by allied screening elements before they reached their targets. 13 VC battalions, however, managed to slip through the cordon and once again plunged the capital into chaos. Severe fighting occurred at Phu Lam, (where it took two days to root out the VC 267th Local Force Battalion), around the Y-Bridge and at Tan Son Nhut.[139] By 12 May, however, it was all over. VC forces withdrew from the area leaving behind over 3,000 dead.[140]

The fighting had no sooner died down around Saigon than U.S. forces in Quảng Tín Province suffered a defeat when the PAVN 2nd Division attacked Kham Duc, the last Special Forces border surveillance camp in I Corps. 1,800 U.S. and ARVN troops were isolated and under intense attack when MACV made the decision to avoid a situation reminiscent of that at Khe Sanh. Kham Duc was evacuated by air while under fire, and abandoned to the North Vietnamese.[141][142]

The PAVN/VC returned to Saigon on 25 May and launched a second wave of attacks on the city. The fighting during this phase differed from Tet Mau Than and "Mini-Tet" in that no U.S. installations were attacked. During this series of actions, VC forces occupied six Buddhist pagodas in the mistaken belief that they would be immune from artillery and air attack. The fiercest fighting once again took place in Cholon. One notable event occurred on 18 June when 152 members of the VC Quyet Thang Regiment surrendered to ARVN forces, the largest communist surrender of the war.[143] The actions also brought more death and suffering to the city's inhabitants. A further 87,000 were made homeless while more than 500 were killed and another 4,500 were wounded.[144] During part of the second phase (5 May – 30 May) U.S. casualties amounted to 1,161 killed and 3,954 wounded,[145][143]

المرحلة الثالثة

Phase III of the offensive began on 17 August and involved attacks in I, II and III Corps. Significantly, during this series of actions only North Vietnamese forces participated and targets were military in nature, with less concise attacks against city-targets. The main offensive was preceded by attacks on the border towns of Tây Ninh, An Lộc, and Loc Ninh, which were initiated in order to draw defensive forces from the cities.[146] A thrust against Da Nang was preempted by the U.S. Marines' Operation Allen Brook. Continuing their border-clearing operations, three PAVN regiments asserted heavy pressure on the U.S. Special Forces camp at Bu Prang, in Quang Duc Province, five kilometers from the Cambodian border. The fighting lasted for two days before the PAVN broke contact; the combat resulted in US/ARVN claiming 776 PAVN/VC casualties, 114 South Vietnamese and two Americans.[147]

Saigon was struck again during this phase, but the attacks were less sustained and once again repulsed. As far as MACV was concerned, the August offensive "was a dismal failure".[148] In five weeks of fighting and after the loss of 20,000 troops, the previous objectives of spurring an uprising and mass-defection had not been attained during this "final and decisive phase". Yet, as historian Ronald Spector has pointed out "the communist failures were not final or decisive either".[148]

The horrendous casualties and suffering endured by PAVN/VC units during these sustained operations were beginning to tell. The fact that there were no apparent military gains made that could possibly justify all the blood and effort just exacerbated the situation. During the first half of 1969, more than 20,000 PAVN/VC troops rallied to allied forces, a threefold increase over the 1968 figure.[149]

انظر أيضاً

- تت 1969

- VC and PAVN battle tactics، بعد تت

المراجع

- ^ Smedberg, p. 188

- ^ "Tet Offensive". National Geographic. May 20, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Tet Offensive | Encyclopedia.com". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ "Tet Offensive | Facts, Casualties, Videos, & Significance | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica (in الإنجليزية). July 16, 2023.

- ^ Hoang Ngoc Lung, The General Offensives McLean VA: General Research Corporation, 1978, p. 8.

- ^ The South Vietnamese government estimated North Vietnamese forces at 323,000, including 130,000 regulars and 160,000 guerrillas. Hoang, p. 10. MACV estimated that strength at 330,000. The CIA and the U.S. State Department concluded that the North Vietnamese force level lay somewhere between 435,000 and 595,000. Dougan and Weiss, p. 184.

- ^ Does not include ARVN or U.S. casualties incurred during the "Border Battles"; ARVN killed, wounded, or missing from Phase III; U.S. wounded from Phase III; or U.S. missing during Phases II and III.

- ^ "These figures are for the period January 31 to February 29."

- ^ Moise, Edwin (2017). The Myths of Tet The most misunderstood event of the Vietnam War. University of Kansas Press. ISBN 978-0700625024.

- ^ Communist Leaders Stoutly Defend Tet Losses – The Washington Post

- ^ Includes casualties incurred during the "Border Battles", Tet Mau Than and the second and third phases of the offensive. General Tran Van Tra claimed that from January through August 1968 the offensive had cost North Vietnam more than 75,000 dead and wounded. This is probably a low estimate. Tran Van Tra, Tet, in Jayne S. Warner and Luu Doan Huynh, eds., The Vietnam War: Vietnamese and American Perspectives. Armonk NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1993, pgs. 49 & 50.

- ^ PAVN's Department of warfare, 124th/TGi, document 1.103 (11-2-1969)

- ^ "Tết Mậu Thân 1968 qua những số liệu – Báo Nhân Dân điện tử". Tết Mậu Thân 1968 qua những số liệu – Báo Nhân Dân điện tử. January 25, 2008. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ أ ب ت Dougan and Weiss, p. 116.

- ^ (ڤيتنامية: Sự kiện Tết Mậu Thân 1968، حرفياً "حدث قرد الأرض يانگ 1968"، أيضاً Tổng tiến công và nổi dậy, Tết Mậu Thân 1968، "هجوم تيت ماو تا المفاجئ والعام"). الاسم الڤيتنامي 'Mau Than' يستخدم الدورة الستينية. 1968 was a year of Yang-Earth (Mậu) Monkey (Thân) in the traditional year-naming cycle.

- ^ Ang, p. 351. Two interpretations of the offensive's goals have continued to dominate Western historical debate. The first maintained that the political consequences of the winter-spring offensive were an intended rather than an unintended consequence. This view was supported by William Westmoreland and his friend Jamie Salt in A Soldier Reports, Garden City NY: Doubleday, 1976, p. 322; Harry G. Summers in On Strategy, Novato CA: Presidio Press, 1982, p. 133; Leslie Gelb and Richard Betts, The Irony of Vietnam, Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1979, pp. 333–334; and Schmitz p. 90. This thesis appeared logical in hindsight, but it "fails to account for any realistic North Vietnamese military objectives, the logical prerequisite for an effort to influence American opinion." James J. Wirtz in The Tet Offensive, Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1991, p. 18. The second thesis (which was also supported by the majority of contemporary captured VC documents) was that the goal of the offensive was the immediate toppling of the Saigon government or, at the very least, the destruction of the government apparatus, the installation of a coalition government, or the occupation of large tracts of South Vietnamese territory. Historians supporting this view are Stanley Karnow in Vietnam, New York: Viking, 1983, p. 537; U.S. Grant Sharp in Strategy for Defeat, San Rafael CA: Presidio Press, 1978, p. 214; Patrick McGarvey in Visions of Victory, Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 1969; and Wirtz, p. 60.

- ^ "U.S. Involvement in the Vietnam War: The Tet Offensive, 1968". United States Department of State. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 8.

- ^ Fallows, James (2020-05-31). "Is This the Worst Year in Modern American History?". The Atlantic (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- ^ Baker, Peter (2017-01-03). "Nixon Tried to Spoil Johnson's Vietnam Peace Talks in '68, Notes Show". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-07-02.

- ^ "The Myths of Tet". kansaspress.ku.edu. Archived from the original on March 11, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "50th Anniversary 1967 Election". October 5, 2017.

- ^ أ ب Willbanks, James H. (2007). The Tet Offensive: A Concise History. Columbia University Press. JSTOR 10.7312/will12840.

- ^ "The Importance of the Vietnam War's Tet Offensive". War on the Rocks. 2018-01-29. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, pp. 22–23

- ^ أ ب Dougan and Weiss, p. 22.

- ^ Hammond, p. 326.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 23.

- ^ Hammond, pp. 326, 327.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 23. This Order of Battle controversy resurfaced in 1982 when Westmoreland filed a lawsuit against CBS News after the airing of its program, The Uncounted Enemy: A Vietnam Deception, which aired had on 23 January 1982.

- ^ Those in the administration and the military who urged a change in strategy included: Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara; Undersecretary of State Nicholas Katzenbach; Assistant Secretary for Far Eastern Affairs William Bundy; Ambassador to South Vietnam Henry Cabot Lodge; General Creighton W. Abrams, deputy commander of MACV; and Lieutenant General Frederick C. Weyand, commander of II Field Force, Vietnam. Lewis Sorley, A Better War. New York: Harvest Books, 1999, p. 6. Throughout the year, the Pentagon Papers claimed, Johnson had discounted any "negative analysis" of U.S. strategy by the CIA and the Pentagon offices of International Security Affairs and System Analysis, and had instead "seized upon optimistic reports from General Westmoreland." Neil Sheehan, et al. The Pentagon Papers as Reported by the New York Times. New York: Ballantine, 1971, p. 592.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 68.

- ^ Karnow, pp. 545–546.

- ^ Karnow, p. 546.

- ^ أ ب Dougan and Weiss, p. 66.

- ^ Schmitz, p. 56.

- ^ Schmitz, p. 58.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 69.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 67.

- ^ Karnow, p. 514.

- ^ Elliot, p. 1055.

- ^ Nguyen, p. 4.; Duiker, William J. (2002) "Foreword," in Military History Institute of Vietnam Victory in Vietnam: A History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975, p. xiv.

- ^ Victory in Vietnam, p. 371.

- ^ Victory in Vietnam, p. 380. Nguyen, fn. 147

- ^ Karnow, p. 555, John Prados, The Blood Road, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998, p. 242.

- ^ Westmoreland, pp. 339–340.

- ^ Oberdorfer, p. 261, See also Palmer, p. 254, and Karnow, p. 534.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةWestmoreland332 - ^ Department of Defense, CACCF: Combat Area [Southeast Asia] Casualties Current File, as of Nov. 1993, Public Use Version. Washington, D.C.: National Archives, 1993.

- ^ Karnow, pp. 544–545.

- ^ Doyle, Lipsman and Maitland, pp. 118, 120.

- ^ أ ب Tran Van Tra, Tet, pp. 49, 50.

- ^ To a lesser extent characterised as mere disappointment in the official history (a heavy characterisation for an official history), Duiker, William J. (2002) "Foreword," in Military History Institute of Vietnam Victory in Vietnam: A History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975, p. xiv.

- ^ Willbanks, p. 80.

- ^ Tran Van Tra, Vietnam, Washington, D.C.: Foreign Broadcast Information Service, 1983, p. 35. There are some extravagant but largely unfounded stories that Tra was severely punished. For example, "This public criticism of the Hanoi leadership led to Tra's removal from the Politburo and house arrest until his death in April 1994." Tra had never been a member of the Politburo. He was not placed under house arrest, even being allowed to travel abroad to attend a conference on the Vietnam War in 1990 and he was allowed to continue writing and publishing on the history of the war; the People's Army Publishing House released his next book in 1992.

- ^ Schmitz, p. 106.

- ^ Schmitz, p. 109.

- ^ Duiker, p. 296. This was mainly due to General Creighton Abrams' new "One War" strategy and the CIA/South Vietnamese Phoenix Program.

- ^ Macmillan Dictionary of Historical Terms. Chris Cook. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-349-10084-2. P. 316

- ^ Nationalism and Imperialism in South and Southeast Asia: Essays Presented to Damodar R. SarDesai. Arnold P. Kaminsky, Roger D. Long. Routledge; 1 edition (September 7, 2016). ISBN 1138234834. P. 49

- ^ أ ب Smedberg, p. 196

- ^ Marilyn Young, The Vietnam Wars: 1945–1990 (New York: Harper Perennial, 1991), p. 223

- ^ According to one estimate by late 1968, of a total of 125,000 main force troops in the South, 85,000 were of North Vietnamese origin. Duiker, p. 303.

- ^ "Vietnam Veterans for Academic Reform". Archived from the original on 2009-02-26.

- ^ Whitcomb, Col Darrel (Summer 2003). "Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975 (book review)". Air & Space Power Journal. Archived from the original on 2009-02-07.

- ^ "Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975." University Press of Kansas, May 2002 (original 1995). Translation by Merle L. Pribbenow. Page 247.

- ^ Pribbenow, p. 249.

- ^ Arnold, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Arnold, p. 91. See also Karnow, 534.

- ^ Karnow, p. 536.

- ^ Doyle, Lipsman and Maitland, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Currey, Cecil B. (2005). Victory at Any Cost: The Genius of Viet Nam's Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap (in الإنجليزية). Potomac Books, Inc. pp. 272–273. ISBN 9781574887426.

- ^ أ ب Warren, James A. (2013-09-24). Giap: The General Who Defeated America in Vietnam (in الإنجليزية). St. Martin's Press. pp. 189–190. ISBN 9781137098917.

- ^ Hoang, p. 118.

- ^ Victory in Vietnam, p. 223.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 118.

- ^ Arnold, p. 90.

- ^ Zaffiri, p. 293.

- ^ Hoang, pp. 135–6.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 119.

- ^ Three of the four ARVN Corps' commanders, for example, were replaced for their dismal performance during the offensive.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 120.

- ^ Hoang, p. 142.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 126.

- ^ أ ب Dougan and Weiss, p. 127.

- ^ Hoang, p. 147.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 128.

- ^ Clifford, pp. 47–55.

- ^ Lorell, Mark & Kelley, Charles, Jr. "Casualties, Public Opinion and Presidential Policy During the Vietnam War" (1985) https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/reports/2007/R3060.pdf pp 71–85

- ^ Laurence, John The Cat from Hue (2002) PublicAffairs Press, New York

- ^ "Vietnam War U.S. Military Fatal Casualty Statistics". 15 August 2016.

- ^ Lorell, Mark & Kelley, Charles, Jr. Casualties, Public Opinion and Presidential Policy During the Vietnam War (1985) https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/reports/2007/R3060.pdf pp 71–85

- ^ Halberstam, David (1979) The Powers That Be, Knopf

- ^ Brinkley, Douglas (2012) Cronkite, Harper

- ^ Clifford, p. 479.

- ^ Smedberg, p. 195.

- ^ Palmer, p. 258.

- ^ Willbanks, pp. 148, 150.

- ^ Zaffiri, p. 304.

- ^ Westmoreland, p. 355.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 70.

- ^ Pentagon Papers, p. 594.

- ^ Westmoreland, p. 356.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةKarnow549 - ^ Schmitz, p. 105.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 72. See also Zaffiri, p. 305.

- ^ Zaffiri, p. 308.

- ^ Clifford, p. 482. See also Zaffiri, p. 309.

- ^ Westmoreland, pp. 356–357.

- ^ Lyndon B. Johnson, The Vantage Point. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston, 1971, pp. 389–392.

- ^ Johnson, pp. 406–407.

- ^ Clifford, p. 485.

- ^ أ ب Pentagon Papers, p. 597.

- ^ The group included McNamara, General Maxwell D. Taylor, Paul H. Nitze (Deputy Secretary of Defense), Henry H. Fowler (Secretary of the Treasury), Nicholas Katzenbach (Undersecretary of State), Walt W. Rostow (National Security Advisor), Richard Helms (Director of the CIA), William P. Bundy (Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs), Paul Warnke (the Pentagon's International Security Affairs), and Philip C. Habib (Bundy's deputy).

- ^ Pentagon Papers, pp. 601–604.

- ^ Pentagon Papers, p. 604.

- ^ Clifford, p. 402.

- ^ Major General Phillip Davidson, Westmoreland's chief of intelligence, reflected how the military men thought about Clifford's conversion in his memoir: "Clifford's use of the Wise Men to serve his dovish ends was a consummate stroke by a master of intrigue...what happened was that Johnson had fired a Doubting Thomas (McNamara) only to replace him with a Judas." Phillip Davidson, Vietnam at War. Novato CA: Presidio Press, 1988, p. 525.

- ^ أ ب Johnson, p. 399.

- ^ Johnson, p. 400.

- ^ Pentagon Papers, p. 623.

- ^ President Johnson was convinced that the source of the leak was the Undersecretary of the Air Force Townsend Hoopes. Don Oberdorfer suggested that the Times pieced the story together from a variety of sources. Oberdorfer, pp. 266–270. Herbert Schindler concluded that the key sources included Senators who had been briefed by Johnson himself. Herbert Y. Schandler, The Unmaking of a President. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1977, pp. 202–205.

- ^ Oberdofer p. 269.

- ^ Stephens, Bret, "American Honor", Wall Street Journal, January 22, 2008, p. 18.

- ^ Braestrup, 1:679f.

- ^ Braestrup, 1:687.

- ^ Johnson, p. 415.

- ^ Clifford, p. 507. The group consisted of Dean Acheson (former Secretary of State), George W. Ball (former Under Secretary of State), General Omar N. Bradley, Arthur H. Dean, Douglas Dillon, (former Secretary of State and the Treasury), Associate Justice Abe Fortas, Henry Cabot Lodge (twice Ambassador to South Vietnam), John J. McCloy (former High Commissioner of West Germany), Robert D. Murphy (former diplomat), General Taylor, General Matthew B. Ridgeway (U.S. Commander in the Korean War), and Cyrus Vance (former Secretary of Defense), and Arthur J. Goldberg (U.S. representative at the UN).

- ^ Karnow, p. 562.

- ^ Clifford, p. 516.

- ^ The four dissenters were Bradley, Murphy, Fortas and Taylor. Karnow, p. 562, Pentagon Papers, p. 610.

- ^ Pentagon Papers, p. 609.

- ^ Clifford, p. 520.

- ^ Zaffiri, pp. 315–316. Westmoreland was "bitter" and was upset that he "had been made the goat for the war." Ibid. See also Westmoreland, pp. 361–362.

- ^ Sorley, p. 18.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 145.

- ^ Shulimson, p. 307. Perhaps more indicative of PAVN losses were the 41 PAVN prisoners taken and the recovery of 500 weapons, 132 of which were crew-served.

- ^ Nolan, Keith (1994). The Magnificent Bastards: The Joint Army-Marine Defense of Dong Ha, 1968. Dell. ISBN 978-0891414858.

- ^ Nolan, Keith (2006). House to House: Playing the Enemy's Game in Saigon, May 1968. Zenith Press. ISBN 9780760323304.

- ^ Hoang, p. 98.

- ^ Spector, p. 166-75.

- ^ Gropman, Allan (1985). Air Power and the Airlift Evacuation of Kham Duc. Office of Air Force History. ISBN 9781477540480.

- ^ أ ب Hoang, p. 101.

- ^ Spector, p. 163.

- ^ Spector, p. 319.

- ^ Spector, p. 235.

- ^ Hoang, p. 110.

- ^ أ ب Spector, p. 240.

- ^ Hoang, p. 117.

ببليوجرافيا

- Hammond, William H. (1988). The United States Army in Vietnam, Public Affairs: The Military and the Media, 1962–1968. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History.

- Hoang Ngoc Lung (1978). The General Offensives of 1968–69. McLean VA: General Research Corporation.

- Military History Institute of Vietnam (2002). Victory in Vietnam: A History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975. trans. Pribbenow, Merle. Lawrence KS: University of Kansas Press. ISBN 0-7006-1175-4.

- Shulimson, Jack; Blaisol, Leonard; Smith, Charles R.; Dawson, David (1997). The U.S. Marines in Vietnam: 1968, the Decisive Year (PDF). History and Museums Division, United States Marine Corps. ISBN 0-16-049125-8.

هذا المقال يضم نصاً من هذا المصدر، الذي هو مشاع.

هذا المقال يضم نصاً من هذا المصدر، الذي هو مشاع. - Shore, Moyars S., III (1969). The Battle of Khe Sanh. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Marine Corps Historical Branch.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Part 1, Part 2 - Vietnam: History of the Bulwark B2 Theater, Volume 5: Concluding the 30 Years War. Southeast Asia Report No. 1247 Archived يوليو 10, 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Washington, D.C.; Foreign Broadcast Information Service; 1983

المصادر الرئيسية

- The 1968 Battles of Quang Tri City& Hue, US Army Center for Military History

- CIA: Intelligence Warning of the Tet Offensive in South Vietnam; An Interim Study Archived أبريل 17, 2016 at the Wayback Machine; April 8, 1968

- The History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; The Joint Chiefs of Staff and the War in Vietnam 1960–68, Part 2, Section 48

- Library of Congress Country Studies: Vietnam & The Tet Offensive. 1987

- MILESTONES: 1961–1968, U.S. Involvement in the Vietnam War: The Tet Offensive, 1968

- Sheehan, Neil; Smith, Hedrick; Kenworthy, E. W.; Butterfield, Fox (1971). The Pentagon Papers. New York: Bantam.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Vietnam January–August 1968, Foreign Relations Series

التاريخانية والذاكرة

- Ang Cheng Guan (July 1998). "Decision-making Leading to the Tet Offensive (1968) – The Vietnamese Communist Perspective". Journal of Contemporary History. 33 (3).

- Arnold, James R. (1990). The Tet Offensive 1968. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-98452-4.

- Blood, Jake (2005). The Tet Effect: Intelligence and the Public Perception of War (Cass Military Studies). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-34997-4.

- Braestrup, Peter (1983). Big Story: How the American Press and Television Reported and Interpreted the Crisis of Tet in Vietnam and Washington. New Haven CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02953-5.

- Bui Diem; Chanoff, David (1999). In the Jaws of History. Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21301-0.

- Bui Tin (2002). From Enemy to Friend: A North Vietnamese Perspective on the War. Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-881-X.

- Clifford, Clark; Holbrooke, Richard (1991). Counsel to the President: A Memoir. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-56995-4.

- Davidson, Phillip (1988). Vietnam at War: The History, 1946–1975. Novato CA: Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-306-5.

- Dougan, Clark; Weiss, Stephen; et al. (1983). Nineteen Sixty-Eight. Boston: Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 0-939526-06-9.

- Doyle, Edward; Lipsman, Samuel; Maitland, Terrance; et al. (1986). The North. Boston: Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 0-939526-21-2.

- Duiker, William J. (1996). The Communist Road to Power in Vietnam. Boulder CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-8587-3.

- Elliot, David (2003). The Vietnamese War: Revolution and Social Change in the Mekong Delta, 1930–1975. 2 vols. Armonk NY: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-7656-0602-X.

- Gilbert, Marc J.; Head, William, eds. (1996). The Tet Offensive. Westport CT: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-95480-3.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hayward, Stephen (April 2004). The Tet Offensive: Dialogues.

- Johnson, Lyndon B (1971). The Vantage Point: Perspectives on the Presidency, 1963–1969. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. ISBN 0-03-084492-4.

- Karnow, Stanley (1991). Vietnam: A History. New York: Penguin. ISBN 0-670-84218-4.

- Laurence, John (2002) The Cat from Hue: a Vietnam War Story, Public Affairs Press (New York), ISBN 1891620312

- Lewy, Gunther (1980). America in Vietnam. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-502732-9.

- Macdonald, Peter (1994). Giap: The Victor in Vietnam. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 1-85702-107-X.

- Maitland, Terrence; McInerney, John (1983). A Contagion of War. Boston: Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 0-939526-05-0.

- Morocco, John (1984). Thunder from Above: Air War, 1941–1968. Boston: Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 0-939526-09-3.

- Nau, Terry L. (2013). "Chapter 4: Tet Changes The War". Reluctant Soldier... Proud Veteran: How a cynical Vietnam vet learned to take pride in his service to the USA. Leipzig: Amazon Distribution GmbH. pp. 27–38. ISBN 9781482761498. OCLC 870660174.

- Nguyen, Lien-Hang T. (2006). "The War Politburo: North Vietnam's Diplomatic and Political Road to the Tet Offensive". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 1 (1–2): 4–58. doi:10.1525/vs.2006.1.1-2.4.

- Oberdorfer, Don (1971). Tet!: The Turning Point in the Vietnam War. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6703-7.

- Palmer, Dave Richard (1978). Summons of the Trumpet: The History of the Vietnam War from a Military Man's Viewpoint. New York: Ballantine.

- Pisor, Robert (1982). The End of the Line: The Siege of Khe Sanh. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-393-32269-6.

- Pike, COL Thomas F. (2013). Military Records, February 1968, 3rd Marine Division: The Tet Offensive. Charleston, SC: Createspace. ISBN 978-1-481219-46-4.

- Pike, COL Thomas F. (2017). I Corps Vietnam: An Aerial Retrospective. Charleston, SC: Createspace. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-36-628720-5. www.tfpike.com

- Prados, John; Stubbe, Ray (1991). Valley of Decision: The Siege of Khe Sanh. Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-395-55003-3.

- Schandler, Herbert Y. (1977). The Unmaking of a President: Lyndon Johnson and Vietnam. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02222-4.

- Schmitz, David F. (2004). The Tet Offensive: Politics, War, and Public Opinion. Westport CT: Praeger. ISBN 0-7425-4486-9.

- Smedberg, Marco (2008). Vietnamkrigen: 1880–1980. Historiska Media. ISBN 978-91-85507-88-7.

- Sorley, Lewis (1999). A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America's Last Years in Vietnam. New York: Harvest Books. ISBN 0-15-601309-6.

- Stanton, Shelby L. (1985). The Rise and Fall of an American Army: U.S. Ground Forces in Vietnam, 1965–1973. New York: Dell. ISBN 0-89141-232-8.

- Spector, Ronald H. (1993). After Tet: The Bloodiest Year in Vietnam. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 0-679-75046-0.

- Tran Van Tra (1994). "Tet: The 1968 General Offensive and General Uprising". In Warner, Jayne S.; Luu Doan Huynh (eds.). The Vietnam War: Vietnamese and American Perspectives. Armonk NY: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 1-56324-131-5.

- Westmoreland, William C. (1976). A Soldier Reports. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-00434-6.

- Wiest, Andrew (2002). The Vietnam War, 1956–1975. London: Osprey Publishers. ISBN 1-84176-419-1.

- Willbanks, James H. (2008). The Tet Offensive: A Concise History. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12841-4.

- Wirtz, James J. (1991). The Tet Offensive: Intelligence Failure in War. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8209-7.

- Zaffiri, Samuel (1994). Westmoreland. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 0-688-11179-3.

وصلات خارجية

- الحكومية

- معلومات عامة

ملاحظات عامة من O.Khiara

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles containing ڤيتنامية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- CS1 errors: generic name

- معارك ڤيتنام

- حملات حرب ڤيتنام

- حملات عسكرية أمريكية

- 1968 في الولايات المتحدة

- نزاعات 1968

- 1968 في ڤيتنام الجنوبية

- Attacks on diplomatic missions of the United States

- معارك وعمليات حرب ڤيتنام في 1968

- Battles of the Vietnam War involving Australia

- Battles of the Vietnam War involving New Zealand

- Battles of the Vietnam War involving Thailand

- Battles of the Vietnam War involving South Korea

- تاريخ ڤيتنام الجنوبية

- Military history of the United States during the Vietnam War