مصادم الهدرونات الكبير

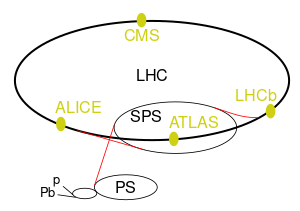

Layout of the LHC complex | |

| الخصائص العامة | |

|---|---|

| نوع المعجل | Synchrotron |

| نوع الشعاع | proton, heavy ion |

| نوع الهدف | collider |

| خصائص الشعاع | |

| الطاقة القصوى | 6.8 TeV per beam (13.6 TeV collision energy) |

| Maximum luminosity | 1×1034/(cm2⋅s) |

| الخصائص الطبيعية | |

| المحيط | 26،659 متر (16.565 ميل) |

| الموقع | Near Geneva, Switzerland; across the border of France and Switzerland. Mostly in France. |

| الإحداثيات | 46°14′06″N 06°02′42″E / 46.23500°N 6.04500°E |

| المؤسسة | CERN |

| تواريخ التشغيل | 2010 – present |

| سبقه | Large Electron–Positron Collider |

| |

| تجارب LHC | |

|---|---|

| أطلس | A Toroidal LHC Apparatus |

| CMS | Compact Muon Solenoid |

| LHCb | LHC-beauty |

| ALICE | A Large Ion Collider Experiment |

| TOTEM | Total Cross Section, Elastic Scattering and Diffraction Dissociation |

| LHCf | LHC-forward |

| LHC preaccelerators | |

| p و Pb | المعجلات الخطية للپروتونات (Linac 2) وLead (Linac 3) |

| (not marked) | Proton Synchrotron Booster |

| PS | Proton Synchrotron |

| SPS | Super Proton Synchrotron |

| |

| المنشآت الحالية للجسيمات والنواة | |

|---|---|

| LHC | يعجل البروتونات والأيونات الثقيلة |

| LEIR | يعجل الأيونات |

| SPS | يعجل البروتونات والأيونات |

| PSB | يعجل البروتونات |

| PS | يعجل البروتونات والأيونات |

| Linac 3 | Injects heavy ions into LEIR |

| Linac4 | يعجل الأيونات |

| AD | Decelerates antiprotons |

| ELENA | Decelerates antiprotons |

| ISOLDE | ينتج أشعة أيونات مشعة |

| MEDICIS | ينتج نظائر لأغراض طبية |

مصادم الهدرونات الكبير (بالإنجليزية: Large Hadron Collider) هو آلة علمية تجريبية كبيرة عبارة عن مُعجِّل جسيمات يستخدمه الفيزيائيون لدراسة الجسيمات ما دون الذرية والتي هى وحدات بناء الكون.

يشار إلى هذا المعجل بالأحرف الأولى من اسمه بالإنجليزية LHC و حاليا هو أكبر مُعجِّل جسيمات في العالم يستخدم في مصادمة أشعة بروتونية طاقتها 7 تيرا (7×1310) إلكترون فولت. في جوهره هو أداة علمية تجريبية الهدف منها اختبار صحة فرضيات و حدود النموذج الفيزيائي القياسي الذي يصف الإطار النظري الحالي لفيزياء الجسيمات. أنشأت المصادمَ المنظمة الأوربية للأبحاث النووية (CERN) وهو موجود تحت الأرض قرب جنيف في المنطقة الحدودية بين سويسرا وفرنسا.[1]

يعد مصادم الهدرونات الكبير أكبر معجلات الجسيمات في العالم حاليا وأعلاها طاقةً[2]، وقد موله وتعاون على بنائه أكثر من ثمانية آلاف فيزيائي من خمسة و ثمانين دولة و مئات من الجامعات و المختبرات، و قد بدأت فكرته في أوائل الثمانينيات و تلقى الموافقة الأولى من مجلس CERN في ديسمبر 1994 وبدأت أعمال الإنشاءات المدنية في أبريل 1998.

مقالات مفصلة: سبر أغوار الذرات

مقالات مفصلة: سبر أغوار الذرات- أنتى-هيدروجين

بعد تمام التركيبات في المصادم وتبريده إلى درجة حرارته التشغيلية النهائية و هي تقريبا 1.9 ك (-271.25 مئوية)، و بعد أن أجري حقن مبدئي لحزم جسيمات فيما بين 8 و 11 أغسطس 2008[3][4]، جرت المحاولة الأولى لتدوير شعاع في المصادم بأكمله يوم 10 سبتمبر 2008[5] في الساعة 7:30 بتوقيت جرينتش. و المصادمة الأولى عالية الطاقة وكان من المخطط أن تحدث بعد افتتاح المصادم رسميا في 21 أكتوبر 2008 [6] الا أنه أقر تأجيلها لنهاية نوفمبر من نفس العام لأسباب تقنية ومع ذلك تأخرت العملية أكثر حتى أصبح هناك تأكيد بمباشرة التجربة في منتصف نوفمبر من العام الحالي 2009.

عند تشغيله وبدء التجارب العملية من المنتظر أن ينتج المصادم الجسيم المخادع بوزون هيگز والذي ستؤدي ملاحظته إلى تأكيد تنبؤات وروابط مفقودة في النموذج القياسي و من الممكن أن تفسر كيف تكتسب الجسيمات الأولية خصائص مثل الكتلة. توكيد وجود بوزون هيگز (أو عدمه) سيكون خطوة هامة على طريق البحث عن نظرية التوحيد الكبرى يُقصد منها توحيد ثلاث من القوى الأساسية الأربعة المعروفة وهي الكهرومغناطيسية والنووية القوية والنووية الضعيفة تاركة الجاذبية فقط خارجها، كما قد يعين بوزون هگز على تفسير لماذا يكون الجذب ضعيفا مقارنة بالقوى الأساسية الأحرى. إلى جوار بوزون هگز يمكن أن تنتج جسيمات نظرية أخرى من المخطط البحث عنها، منها الغريبات والثقوب السوداء الصغروية والأقطاب المغناطيسية الأحادية والجسيمات فائقة التناظر.

وقد أثيرت مخاوف حول أمان المصادم من حيث أن تصادمات الجسيمات عالية الطاقة قد تنجم عنها كوارث، منها إنتاج ثقوب سوداء صغروية ثابتة و غريبات، ونتيجة لهذا نشرت عدة تقارير لحساب CERN تلتها أوراق بحثية تؤكد على أمان تجارب مصادمة الجسيمات. إلا أن إحدى الأوراق البحثية نشرت يوم 10 أغسطس 2008 تصل إلى نتيجة معاكسة مفادها أن "في حدود المعرفة العالية يوجد خطر غير محدد من إنتاج ثقوب سوداء صغروية ثابتة في المصادمات"، وتقترح الورقة خطوات يمكن أن تساعد على تقليل الخطر.

مقالة مفصلة: مسافرون عبر الزمن هنا في أسابيع

مقالة مفصلة: مسافرون عبر الزمن هنا في أسابيع

خلفية

The term hadron refers to subatomic composite particles composed of quarks held together by the strong force (analogous to the way that atoms and molecules are held together by the electromagnetic force).[7] The best-known hadrons are the baryons such as protons and neutrons; hadrons also include mesons such as the pion and kaon, which were discovered during cosmic ray experiments in the late 1940s and early 1950s.[8]

A collider is a type of a particle accelerator that brings two opposing particle beams together such that the particles collide. In particle physics, colliders, though harder to construct, are a powerful research tool because they reach a much higher center of mass energy than fixed target setups. [9] Analysis of the byproducts of these collisions gives scientists good evidence of the structure of the subatomic world and the laws of nature governing it. Many of these byproducts are produced only by high-energy collisions, and they decay after very short periods of time. Thus many of them are hard or nearly impossible to study in other ways.[10]

الغرض

Many physicists hope that the Large Hadron Collider will help answer some of the fundamental open questions in physics, which concern the basic laws governing the interactions and forces among the elementary objects, the deep structure of space and time, and in particular the interrelation between quantum mechanics and general relativity.[11]

Data is also needed from high-energy particle experiments to suggest which versions of current scientific models are more likely to be correct – in particular to choose between the Standard Model and Higgsless model and to validate their predictions and allow further theoretical development.

Issues explored by LHC collisions include:[12][13]

- Is the mass of elementary particles being generated by the Higgs mechanism via electroweak symmetry breaking?[14] It was expected that the collider experiments will either demonstrate or rule out the existence of the elusive Higgs boson, thereby allowing physicists to consider whether the Standard Model or its Higgsless alternatives are more likely to be correct.[15][16]

- Is supersymmetry, an extension of the Standard Model and Poincaré symmetry, realized in nature, implying that all known particles have supersymmetric partners?[17][18][19]

- Are there extra dimensions,[20] as predicted by various models based on string theory, and can we detect them?[21]

- What is the nature of the dark matter that appears to account for 27% of the mass–energy of the universe?

Other open questions that may be explored using high-energy particle collisions:

- It is already known that electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force are different manifestations of a single force called the electroweak force. The LHC may clarify whether the electroweak force and the strong nuclear force are similarly just different manifestations of one universal unified force, as predicted by various Grand Unification Theories.

- Why is the fourth fundamental force (gravity) so many orders of magnitude weaker than the other three fundamental forces? See also Hierarchy problem.

- Are there additional sources of quark flavour mixing, beyond those already present within the Standard Model?

- Why are there apparent violations of the symmetry between matter and antimatter? See also CP violation.

- What are the nature and properties of quark–gluon plasma, thought to have existed in the early universe and in certain compact and strange astronomical objects today? This will be investigated by heavy ion collisions, mainly in ALICE, but also in CMS, ATLAS and LHCb. First observed in 2010, findings published in 2012 confirmed the phenomenon of jet quenching in heavy-ion collisions.[22][23][24]

التصميم

يعتبر هذا المصادم هو الأضخم والأعلى طاقة مصادم لتسريع الجسيمات بالعالم. ويكون في نفق دائري مطوق بمسافة 27 كم (17 ميل) على عمق ما بين 50 إلى 175 متر تحت سطح الأرض[25] وبقطر 3.8 امتار، ومغلف بالخرسانة الاسمنتية، تم انشاؤه ما بين 1983 و 1988[26]. وقد كان يستخدم سابقا كمخزن لمصادم الكترون-بوزيترون العملاق، ويعبر النفق الحدود السويسرية الفرنسية باربعة اماكن وإن كان معظمها داخل فرنسا. وتحتوي المباني السطحية على المعدات المكملة مثل الضواغط، ومعدات التهوية، ومراقبة الإلكترونات ومصانع التبريد. يحتوي نفق المصادم على حزمة من انبوبين متجاورين، كل منهما يحتوي على حزمة بروتون (والبروتون هو نوع واحد من الهدرون). وكلا الحزمتين تكونا بإتجاهين متعاكسين خلال النفق ويوجد حوالي 1.232 من المغناطيسات ثنائية الإستقطاب (dipole magnet) والتي تبقي الحزمة في الطريق الدائري الصحيح، بينما أضيف لها 392 مغناطيس رباعي الأقطاب (Quadrupole magnets) للإبقاء على تركيز الحزمة، ولأجل رفع فرص التفاعل ما بين الجسيمات في نقاط التفاعل الأربع، حيث تمر بها الحزمتين. وبالإجمالي تم تركيب أكثر من 1600 مغناطيس شديد التوصيل وبوزن يزيد على 27 طن.

هناك حاجة لحوالي 96 طنا من الهليوم السائل للإبقاء على درجة حرارة تشغيل المغناطيس (1.9 كالفن) جاعلا من المصادم أكبر وحدة تجميد بالعالم بما تحتوي من سائل الهيليوم المبرد للحرارة[27].

تسرع البروتونات مرة أو مرتان يوميا من 450 جيجا الكترون فولت إلى 7 تيرا الكترون فولت، وسيزداد مجال التوصيل الضخم للمغناطيس الثنائي من 0.54 T إلى 8.3 T.

| الكشاف | الوصف |

|---|---|

| أطلس | one of two general purpose detectors. ATLAS will be used to look for signs of new physics, including the origins of mass and extra dimensions. |

| CMS | the other general purpose detector will, like ATLAS, hunt for the Higgs boson and look for clues to the nature of dark matter. |

| ALICE | will study a "liquid" form of matter called quark–gluon plasma that existed shortly after the Big Bang. |

| LHCb | equal amounts of matter and antimatter were created in the Big Bang. LHCb will try to investigate what happened to the "missing" antimatter. |

الموارد الحاسوبية والتحليلية

Data produced by LHC, as well as LHC-related simulation, were estimated at about 200 petabytes per year.[28]

تم انشاء شبكة مصادم الهادرون الكبير للحوسبة أو بلانجليزية LHC Computing Grid وذلك للتحكم بالكم الضخم من البيانات التي تنتج من مصادم الهدرونات. وهى تضم خطوط الياف ضوئية محلية بجانب خط انترنت عالى السرعة لمشاركة البيانات بين الوكالة و المعاهد و المعامل على مستوى العالم.

نظام الحوسبة الموزع أو بلانجليزية Distributed Computing و اسمة مصادم الهدرونات الكبير@المنزل أو بلانجليزية LHC@Home تم العمل فية ليدعم بناء وتقويم المصادم وهو يستخدم نظام بوينك لمحاكة كيفية انتقال الجزيئات في القناة وبهذة المعلومات سيتمكن العلماء من ضبط المغناطيس للحصول على أفضل دوران مستقر للاشعة حول الحلقات في المصادم

تاريخ التشغيل

The LHC first went operational on 10 September 2008,[29] but initial testing was delayed for 14 months from 19 September 2008 to 20 November 2009, following a magnet quench incident that caused extensive damage to over 50 superconducting magnets, their mountings, and the vacuum pipe.[30][31][32][33][34]

During its first run (2010–2013), the LHC collided two opposing particle beams of either protons at up to 4 teraelectronvolts (4 TeV or 0.64 microjoules), or lead nuclei (574 TeV per nucleus, or 2.76 TeV per nucleon).[35][36] Its first run discoveries included the long-sought Higgs boson, several composite particles (hadrons) like the χb (3P) bottomonium state, the first creation of a quark–gluon plasma, and the first observations of the very rare decay of the Bs meson into two muons (Bs0 → μ+μ−), which challenged the validity of existing models of supersymmetry.[37]

الإنشاء

تحديات التشغيل

The size of the LHC constitutes an exceptional engineering challenge with unique operational issues on account of the amount of energy stored in the magnets and the beams.[38][39] While operating, the total energy stored in the magnets is 10 GJ (2،400 kilograms of TNT) and the total energy carried by the two beams reaches 724 MJ (173 kilograms of TNT).[40]

Loss of only one ten-millionth part (10−7) of the beam is sufficient to quench a superconducting magnet, while each of the two beam dumps must absorb 362 MJ (87 kilograms of TNT). These energies are carried by very little matter: under nominal operating conditions (2,808 bunches per beam, 1.15×1011 protons per bunch), the beam pipes contain 1.0×10−9 gram of hydrogen, which, in standard conditions for temperature and pressure, would fill the volume of one grain of fine sand.

التكلفة

تقدر التكلفة الاجمالية للمشروع ما بين 3.2 إلى 6.4 مليار يورو. تمت الموافقة على البناء في 1995 بميزانية 1.6 مليار يورو بلإضافة إلى 140 مليون يورو لتغطية تكلفة التجارب. ومع ذلك ففى عام 2001 تمت مراجعة التكلفة فتبين انها تخطت ما هو مقدر لها بحوالى 300 مليون يورو للمعجل أو المسرع و 30 مليون يورو للتجارب ومع انخفاض ميزانية الوكالة تم تاجيل ميعاد الانتهاء من سنة 2005 إلى سنة 2007. تم انفاق 120 مليون يورو من الميزانية المضافة على المغناطيس عالى التوصيل. كما كان هناك العديد من المصاعب الهندسية حدثت أثناء انشاء كهف تحت الأرض لمكتشف الجزيئات العام Compact Muon Solenoid.وكان هناك مصاعب أخرى بسبب تقديم اجزاء أو معدات بها خلل للوكالة من خلال بعض معامل الابحاث المشاركة مثل معمل أرگون الوطني و معمل فرمي.

استبعاد روسيا

أمان مصادمة الجزيئات

كانت أثيرت مخاوف حول أمان مخطط التجارب التي ستجرى بواسطة المصادم في وسائل الاعلام والمحاكم[41]. و بالرغم من أن تلك المخاوف لا تعدم أسسا علمية نظرية تستند إليها إلا أن التوافق العام في الآراء في المجتمع العلمي هو أنه لا يوجد اي تصور واضح الخطر الناتج عن اصطدام الجسيمات في مصادم الهدرونات الكبير LHC[42].

يقول بعض الخبراء إلى ان تصادم الجزيئات قد ينتج عنه ثقب أسود قد يلتهم الأرض كلها. في حين يشير البعض إلى إمكانية إنتاج المادة الغريبة strangelet التي يمكن أن تلتهم الأرض أيضا. في حين يذهب بعض الخبراء إلى أن التركيبة أو معاملات الكونية ليست في حالة مستقرة و أن هذا الاختيار قد يعطي إشارة الإنتقال نجو حالة أكثر إستقرارا (يشبه تأثير الفراشة) ينقلب جزئ كبير من الكون فيه إلى فراغ أو ما يعرف بال voids أو vacuum bubble.

أما مصادر التخوف الأخرى فهي نشوء أقطاب مغناطيسية أحادية magnetic monopole تسبب في تلاشي البروتونات، إضافة إلى الإشعاعات الكونية المنبعثة عنها. و قد أسست سرن CERN أي مركز البحوث النووي الأوروبي صفحة ترد فيها بشكل مقتضب على هذه المخاوف لكن لا تجزم بعدم إمكانية وقوعها. فأما عن الثقوب السوداء فهي تقول أنها يمكن أن تكون لكن عمرها سيكون من القصر بحيث لا تتمكن من إمتصاص أية مادة بداخلها مما لا يجعلها اي مصدر للقلق في حين يرد البعض بان إنتاج ثقب أسود مستقر فرضية واردة. [1]

مشاكل تقنية

- في 19 سبتمبر 2008 احدث خلل في التبريد انحناء في 100 قطب مغناطيسي في القطاعات 3-4 متسببا في تسرب ما يفارب 6 طن من الهيليوم في القناة وبالتالي ارتفاع في درجة الحرارة حوالي 100 درجة كلفن. هذه الحادثة قد تؤجل التجربة بضع أشهر على الاقل حتى يتم اعادة تبريد المغانط المتأثرة [43][44]. تم مؤخرا الإعلان عن موعد الانتهاء من الإصلاح وبدء التجربة في منتصف نوفمبر 2009.

- تمكن بعض قراصنة الكمبيوتر من الولوج إلى أحد حواسيب المركز و ترك رسالة سخرية من العلماء و نظام أمنهم الحاسوبي.

تأخيرات البناء

اكتشاف وجود عطل في مسرع الجزيئات

عودة المصادم للعمل في نوفمبر 2009

عاد «مصادم هادرون الكبير» Large Hadron Collider بعد توقّف قسريّ دام ما يزيد عن السنة. والمعلوم أنه يدار من قِبل «المركز الأوروبي للبحوث النووية» «سيرن» CERN. وانطلقت حزم الجزيئات الذرية فيه لتدور باتجاه عقارب الساعة، في ممراته التي يصل طولها الى 27.4 كيلومتراً، عند الحدود الفرنسية السويسرية، بطاقة 3.5 تيرا - إلكترون فولت («تيرا» تعني ألف بليون، والإلكترون فولت وحدة لقياس الطاقة على مستوى الذرّة). والمعلوم ان أشعة الضوء المرئي تحمل كميات كبيرة من الطاقة على شكل كرات صغيرة، يطلق على كل منها اسم «فوتون». ويحمل الفوتون طاقة معدّلها حوالى 2 إلكترون فولت. وفي المقابل، فإن كل «فوتون» في «أشعة - إكس» المستعملة في التصوير الطبي، يحمل قرابة ألف إلكترون فولت.[45]

ولا تمثل طاقة الـ3.5 تيرا - إلكترون فولت أقصى ما يمكن الجهاز إنتاجه من الطاقة. ويأتي هذا الخيار بعد التدقيقات والمراجعات التي خضعت لها الموصلات الكهربائية ذات التيار العالي للجهاز وانتهت في الصيف الفائت.

وفي حديث الى وسائل الإعلام، قال رولف هووِر المدير العام لمركز سيرن: «اخترنا طاقة 3.5 تيرا - إلكترون فولت كبداية لأنها تتيح لمشغلي «مُصادم هادرون» أن يُطوّروا خبراتهم في تشغيل الجهاز بأمان، أثناء السلسلة الجديدة من الاختبارات». ويعتبر مُصادم «هادرون» الأضخم عالمياً، والأكثر تقدماً أيضاً، ما يجعل نتائج تجاربه مهمة لعلوم الفيزياء الذرية عموماً، وخصوصاً تلك التي تبحث في الطاقة العالية ونظريات الفيزياء الكمومية. وقدّمت الولايات المتحدة خبرة 150عالماً لدعم هذا المشروع الأوروبي الضخم.

والمعلوم أن حريقاً شبّ في أحد موصلات الطاقة في الجهاز، في 19 أيلول (سبتمبر) 2008، ما تسبّب بإيقاف تشغيل المُصادم. وتوجّب على العلماء، حينها، انتظار تبريده قبل الشروع بصيانته وإصلاح أعطاله، واستبدال الملفات المحروقة فيه. وتضمّنت تلك العملية إعادة تفحّص عشرة آلاف ناقل للكهرباء من النوع الفائق التوصيل (يسمى «سوبر كوندكاتر» Super Conductor)، تساهم في التيار العالي الذي يتدفق في الجهاز، والذي أدى خلل فيه الى احتراق المُصادِم في العام الماضي.

وفي حالتها العادية، تتمتع الأجهزة الفائقة التوصيل بمقاومة متدنية جداً للكهرباء، ما يعني انخفاض ما يتولد حولها من حرارة. في عدد قليل من الحالات، تُظهر تلك الموصلات الفائقة مقاومة غير مألوفة، ما يؤدي الى كثير من الخلل في عمل المُصادم، وكذلك يوجب استبدال تلك الموصِلات الشاذة. وفي وضعه الراهن، بات «مُصادم هادرون الكبير» على مستوى عالٍ من الأمان، ما طمأن المسؤولين عنه الى انه سيعمل لعام على الأقل من دون صيانة أخرى. وعبر هووِر عن هذا الأمر قائلاً: «أصبح «مُصادم هادرون» أكثر قابلية للفهم مما كان عليه السنة الماضية، وبإمكاننا اليوم التطلع إلى الأمام بثقة أكبر وحماسة لتشغيل ناجح ومنتظم خلال الشتاء المقبل والسنة المقبلة كذلك».

ويتضمّن مخطط التشغيل لعام 2009 ضخّ حزمات في اتجاهين متعاكسين داخل الأنبوب المغناطيسي، ثم مصادمتهما لاحقاً، وكذلك رفع الطاقة إلى المستوى الذي تتطلبه الاختبارات المُعقّدة التي تُجرى فيه. وتبدأ عملية تسجيل البيانات والمعطيات الناتجة من اصطدام الجزيئات بعد أسابيع قليلة من إنطلاق العمل. ويستمر هذا المُصادم في العمل بطاقة 3.5 تيرا - إلكترون فولت، خلال المراحل الأولى من عمله، ما سيزيد من خبرة فريق العاملين على الجهاز. بعد ذلك، يرفع مستوى الطاقة الى 5 تيرا - إلكترون فولت. و في نهاية 2010، يعمل «مُصادم هادرون» بحزم من أيونات الرصاص، للمرة الأولى. ثم يطفأ تمهيداً لتشغيله بطاقة 7 تيرا - إلكترون فولت، وهي طاقة غير مسبوقة في تجارب الفيزياء الجزيئية والنووية حاضراً.

خط زمني

| التاريخ | الحدث |

|---|---|

| 10 سبتمبر 2008 | CERN successfully fired the first protons around the entire tunnel circuit in stages. |

| 19 Sep 2008 | Magnetic quench occurred in about 100 bending magnets in sectors 3 and 4, causing a loss of approximately 6 tonnes of liquid helium. |

| 30 سبتمبر 2008 | أول "modest" high-energy collisions planned but postponed due to accident. |

| 16 اكتوبر 2008 | CERN released a preliminary analysis of the incident. |

| 21 اكتوبر 2008 | الافتتاح الرسمي. |

| 5 ديسمبر 2008 | CERN released detailed analysis. |

| 20 نوفمبر 2009 | Low-energy beams circulated in the tunnel for the first time since the incident.[46] |

| 23 نوفمبر 2009 | First particle collisions[34] |

| 30 نوفمبر 2009 | LHC becomes the world's highest energy particle accelerator achieving 1.18 TeV per beam, beating the Tevatron's previous record of 0.98 TeV per beam held for eight years.[47] |

| 28 فبراير 2010 | The LHC continues operations ramping energies to run at 3.5 TeV for 18 months to two years, after which it will be shut down to prepare for the 14 TeV collisions (7 TeV per beam).[48] |

| 30 مارس 2010 | تم عمل تجربتين تصادم بقوة 7 TeV في مركز سيرن 13:06 حسب التوقيت المحلي، كبداية لبرنامج أبحاث التصادم. |

| 8 Nov 2010 | Start of the first run with lead ions. |

| 6 Dec 2010 | End of the run with lead ions. Shutdown until early 2011. |

| 13 Mar 2011 | Beginning of the 2011 run with proton beams.[49] |

| 21 Apr 2011 | LHC becomes the world's highest-luminosity hadron accelerator achieving a peak luminosity of 4.67·1032 cm−2s−1, beating the Tevatron's previous record of 4·1032 cm−2s−1 held for one year.[50] |

| 24 May 2011 | ALICE reports that a Quark–gluon plasma has been achieved with earlier lead collisions.[51] |

| 17 Jun 2011 | The high-luminosity experiments ATLAS and CMS reach 1 fb−1 of collected data.[52] |

| 14 Oct 2011 | LHCb reaches 1 fb−1 of collected data.[53] |

| 23 Oct 2011 | The high-luminosity experiments ATLAS and CMS reach 5 fb−1 of collected data. |

| Nov 2011 | Second run with lead ions. |

| 22 Dec 2011 | First new composite particle discovery, the χb (3P) bottomonium meson, observed with proton–proton collisions in 2011.[54] |

| 5 Apr 2012 | First collisions with stable beams in 2012 after the winter shutdown. The energy is increased to 4 TeV per beam (8 TeV in collisions).[55] |

| 4 Jul 2012 | First new elementary particle discovery, a new boson observed that is "consistent with" the theorized Higgs boson. (This has now been confirmed as the Higgs boson itself.[56]) |

| 8 Nov 2012 | First observation of the very rare decay of the Bs meson into two muons (Bs0 → μ+μ−), a major test of supersymmetry theories,[57] shows results at 3.5 sigma that match the Standard Model rather than many of its super-symmetrical variants. |

| 20 Jan 2013 | Start of the first run colliding protons with lead ions. |

| 11 Feb 2013 | End of the first run colliding protons with lead ions. |

| 14 Feb 2013 | Beginning of the first long shutdown to prepare the collider for a higher energy and luminosity.[58] |

| Long Shutdown 1 | |

| 7 Mar 2015 | Injection tests for Run 2 send protons towards LHCb & ALICE |

| 5 Apr 2015 | Both beams circulated in the collider.[59] Four days later, a new record energy of 6.5 TeV per proton was achieved.[60] |

| 20 May 2015 | Protons collided in the LHC at the record-breaking collision energy of 13 TeV.[61] |

| 3 Jun 2015 | Start of delivering the physics data after almost two years offline for recommissioning.[62] |

| 4 Nov 2015 | End of proton collisions in 2015, start of preparations for ion collisions. |

| Nov 2015 | Ion collisions at a record-breaking energy of more than 1 PeV (1015 eV)[63] |

| 13 Dec 2015 | End of ion collisions in 2015 |

| 23 Apr 2016 | Data-taking in 2016 begins |

| 29 June 2016 | The LHC achieves a luminosity of 1.0 · 1034 cm−2s−1, its design value.[64] Further improvements over the year increased the luminosity to 40% above the design value.[65] |

| 26 Oct 2016 | End of 2016 proton–proton collisions |

| 10 Nov 2016 | Beginning of 2016 proton–lead collisions |

| 3 Dec 2016 | End of 2016 proton–lead collisions |

| 24 May 2017 | Start of 2017 proton–proton collisions. During 2017, the luminosity increased to twice its design value.[66] |

| 10 Nov 2017 | End of regular 2017 proton–proton collision mode.[66] |

| 17 Apr 2018 | Start of 2018 proton–proton collisions. |

| 12 Nov 2018 | End of 2018 proton operations at CERN.[67] |

| 3 Dec 2018 | End of 2018 lead-ion run.[67] |

| 10 Dec 2018 | End of 2018 physics operation and start of Long Shutdown 2.[67] |

| Long Shutdown 2 | |

| 22 Apr 2022 | LHC becomes operational again.[68] |

بدء العمل

في 30 مارس، 2010، بدأت أولى تجارب المصادم الكبير بهدف احداث تصادمات لمحاكاة الظروف التي أعقبت الانفجار العظيم للتعرف على كيفية نشأة الكون. وبعد يوم واحد من النجاح في احداث تصادمات بين جسيمات بطاقة قياسية بمعدل 50 تصادما في الثانية بدأوا يوم الاربعاء محاولات لزيادة العدد الى 300 في الثانية داخل مصادم الهدرونات الكبير في سيرن. وقال المتحدث جيمس جيليز بينما كان المزيد من حزم الجسيمات يضخ في اتجاهين متقابلين في مسار بيضاوي داخل نفق المصادم البالغ طول محيطه 27 كيلومترا في المجمع البحثي الواقع تحت منطقة الحدود السويسرية الفرنسية المشتركة قرب جنيف "نحن نتجه الى افاق علمية جديدة." لكن جيليز ذكر أن احداث المزيد من المصادمات أرجيء الى وقت لاحق يوم الاربعاء ليتمكن العلماء من اصلاح بعض أوجه الخلل البسيطة في الالة الضخمة المعقدة. وأدت مشاكل مماثلة الى تأجيل انطلاق البرنامج مرتين يوم الثلاثاء.

وأضاف "لا شيء مما حدث اليوم من شأنه أن يوقف العرض. نحن مستمرون. المشاكل البسيطة أمر طبيعي في مشروع بهذا الحجم."

والهدف هو زيادة تدفق المعلومات في الشهور المقبلة عما يحدث عندما تتصادم الجسيمات بقوة اجمالية تبلغ سبعة تريليونات الكترون فولت وبسرعة تكاد تقترب من سرعة الضوء.

واقتربت المصادمات بمثل هذه القوة جدا من محاكاة الاحداث التي وقعت بعد كسور متناهية الصغر من الثانية من الانفجار العظيم الحقيقي الذي وقع قبل 13.7 مليار عام ونتج عنها نشأة المجرات والنجوم والحياة على الارض وربما حياة في عوالم أخرى مجهولة.

وذكر جيليز أن عدد حزم الجسيمات سيزاد من اثنتين في المرة كما حدث في تجربة يوم الثلاثاء لما يصل الى 2700 خلال الفترة الاولى التي تستمر بين 18 شهرا وعامين من المرحلة الاولى من " الفيزياء الجديدة" في مشروع مصادم الهدرونات الكبير الذي تكلف 9.4 مليار دولار.

ويقول علماء من خارج التجربة ان سيرن تعرض بقاء الجنس البشري للخطر مع احتمال أن تنجم عن التجربة أيضا ثقوب سوداء صغيرة مماثلة للثقوب السوداء العملاقة الموجودة في قلب معظم المجرات والتي تبتلع كل ما يقترب منها.

وينفي العلماء في مشروع مصادم الهدرونات الكبير هذا الاحتمال. وقال دنيس دنيجريس عالم الفيزياء في سيرن "الثقوب السوداء التي قد تظهر خلال مصادماتنا ستبقى جزءا من الثانية ثم تتلاشى وهي لا تمثل خظرا على الجنس البشري."

واذا لم تحدث مشاكل كبيرة سيستمر ضخ حزم الجسيمات داخل مصادم الهدرونات الكبير يوميا حتى قرب نهاية عام 2011 وعندئذ سيتوقف المشروع الضخم عاما لاعداد المصادم لمصادمات أقوى.

وبدءا من عام 2013 سيجري احداث مصادمات الجسيمات بقوة اجمالية 14 تريليون الكترون فولت الامر الذي قد ينتج عنه ما يسميه سيرجيو برتولوتشي مدير الابحاث في سيرن "مجهولات مجهولة" أي جوانب خفية مفاجئة لتكوين الكون.

ويقول الباحثون في سيرن ان من المرجح في تلك المرحلة اكتشاف جسيم بوزون هيجز الافتراضي الذي ساعد على التحام المكونات الاولية للمادة في أعقاب الانفجار العظيم وأعطاها تماسكها وكتلتها. [70]

المشاهدات والاكتشافات

An initial focus of research was to investigate the possible existence of the Higgs boson, a key part of the Standard Model of physics which was predicted by theory, but had not yet been observed before due to its high mass and elusive nature. CERN scientists estimated that, if the Standard Model was correct, the LHC would produce several Higgs bosons every minute, allowing physicists to finally confirm or disprove the Higgs boson's existence. In addition, the LHC allowed the search for supersymmetric particles and other hypothetical particles as possible unknown areas of physics.[35] Some extensions of the Standard Model predict additional particles, such as the heavy W' and Z' gauge bosons, which are also estimated to be within reach of the LHC to discover.[71]

أول تشغيل (البيانات المأخوذة 2009–2013)

The first physics results from the LHC, involving 284 collisions which took place in the ALICE detector, were reported on 15 December 2009.[72] The results of the first proton–proton collisions at energies higher than Fermilab's Tevatron proton–antiproton collisions were published by the CMS collaboration in early February 2010, yielding greater-than-predicted charged-hadron production.[73]

After the first year of data collection, the LHC experimental collaborations started to release their preliminary results concerning searches for new physics beyond the Standard Model in proton–proton collisions.[74][75][76][77] No evidence of new particles was detected in the 2010 data. As a result, bounds were set on the allowed parameter space of various extensions of the Standard Model, such as models with large extra dimensions, constrained versions of the Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model, and others.[78][79][80]

On 24 May 2011, it was reported that quark–gluon plasma (the densest matter thought to exist besides black holes) had been created in the LHC.[51]

Between July and August 2011, results of searches for the Higgs boson and for exotic particles, based on the data collected during the first half of the 2011 run, were presented in conferences in Grenoble[81] and Mumbai.[82] In the latter conference, it was reported that, despite hints of a Higgs signal in earlier data, ATLAS and CMS exclude with 95% confidence level (using the CLs method) the existence of a Higgs boson with the properties predicted by the Standard Model over most of the mass region between 145 and 466 GeV.[83] The searches for new particles did not yield signals either, allowing to further constrain the parameter space of various extensions of the Standard Model, including its supersymmetric extensions.[84][85]

On 13 December 2011, CERN reported that the Standard Model Higgs boson, if it exists, is most likely to have a mass constrained to the range 115–130 GeV. Both the CMS and ATLAS detectors have also shown intensity peaks in the 124–125 GeV range, consistent with either background noise or the observation of the Higgs boson.[86]

On 22 December 2011, it was reported that a new composite particle had been observed, the χb (3P) bottomonium state.[54]

On 4 July 2012, both the CMS and ATLAS teams announced the discovery of a boson in the mass region around 125–126 GeV, with a statistical significance at the level of 5 sigma each. This meets the formal level required to announce a new particle. The observed properties were consistent with the Higgs boson, but scientists were cautious as to whether it is formally identified as actually being the Higgs boson, pending further analysis.[87] On 14 March 2013, CERN announced confirmation that the observed particle was indeed the predicted Higgs boson.[88]

On 8 November 2012, the LHCb team reported on an experiment seen as a "golden" test of supersymmetry theories in physics,[57] by measuring the very rare decay of the meson into two muons (). The results, which match those predicted by the non-supersymmetrical Standard Model rather than the predictions of many branches of supersymmetry, show the decays are less common than some forms of supersymmetry predict, though could still match the predictions of other versions of supersymmetry theory. The results as initially drafted are stated to be short of proof but at a relatively high 3.5 sigma level of significance.[89] The result was later confirmed by the CMS collaboration.[90]

In August 2013, the LHCb team revealed an anomaly in the angular distribution of B meson decay products which could not be predicted by the Standard Model; this anomaly had a statistical certainty of 4.5 sigma, just short of the 5 sigma needed to be officially recognized as a discovery. It is unknown what the cause of this anomaly would be, although the Z' boson has been suggested as a possible candidate.[91]

On 19 November 2014, the LHCb experiment announced the discovery of two new heavy subatomic particles, Error no symbol defined and Error no symbol defined. Both of them are baryons that are composed of one bottom, one down, and one strange quark. They are excited states of the bottom Xi baryon.[92][93]

The LHCb collaboration has observed multiple exotic hadrons, possibly pentaquarks or tetraquarks, in the Run 1 data. On 4 April 2014, the collaboration confirmed the existence of the tetraquark candidate Z(4430) with a significance of over 13.9 sigma.[94][95] On 13 July 2015, results consistent with pentaquark states in the decay of bottom Lambda baryons (Λ0b) were reported.[96][97][98]

On 28 June 2016, the collaboration announced four tetraquark-like particles decaying into a J/ψ and a φ meson, only one of which was well established before (X(4274), X(4500) and X(4700) and X(4140)).[99][100]

In December 2016, ATLAS presented a measurement of the W boson mass, researching the precision of analyses done at the Tevatron.[101]

ثاني تشغيل (2015–2018)

At the conference EPS-HEP 2015 in July, the collaborations presented first cross-section measurements of several particles at the higher collision energy.

On 15 December 2015, the ATLAS and CMS experiments both reported a number of preliminary results for Higgs physics, supersymmetry (SUSY) searches and exotics searches using 13 TeV proton collision data. Both experiments saw a moderate excess around 750 GeV in the two-photon invariant mass spectrum,[102][103][104] but the experiments did not confirm the existence of the hypothetical particle in an August 2016 report.[105][106][107]

In July 2017, many analyses based on the large dataset collected in 2016 were shown. The properties of the Higgs boson were studied in more detail and the precision of many other results was improved.[108]

As of March 2021, the LHC experiments have discovered 59 new hadrons in the data collected during the first two runs.[109]

On 5 July 2022 LHCb reported the discovery of a new type of pentaquark made up of a charm quark and a charm antiquark and an up, a down and a strange quark, observed in an analysis of decays of charged B mesons.[110]

الخطط المستقبلية

"High-luminosity" upgrade

After some years of running, any particle physics experiment typically begins to suffer from diminishing returns: as the key results reachable by the device begin to be completed, later years of operation discover proportionately less than earlier years. A common response is to upgrade the devices involved, typically in collision energy, luminosity, or improved detectors. In addition to a possible increase to 14 TeV collision energy, a luminosity upgrade of the LHC, called the High Luminosity Large Hadron Collider, started in June 2018 that will boost the accelerator's potential for new discoveries in physics, starting in 2027.[111] The upgrade aims at increasing the luminosity of the machine by a factor of 10, up to 1035 cm−2s−1, providing a better chance to see rare processes and improving statistically marginal measurements.[112]

المصادم الدائري المستقبلي المقترح

CERN has several preliminary designs for a Future Circular Collider (FCC)—which would be the most powerful particle accelerator ever built—with different types of collider ranging in cost from around €9 billion (US$10.2 billion) to €21 billion. It would use the LHC ring as preaccelerator, similar to how the LHC uses the smaller Super Proton Synchrotron. It is CERN’s opening bid in a priority-setting process called the European Strategy for Particle Physics Update, and will affect the field’s future well into the second half of the century. As of 2023, no fixed plan exists and it is unknown if the construction will be funded.[113]

الثقافة الشعبية

The Large Hadron Collider gained a considerable amount of attention from outside the scientific community and its progress is followed by most popular science media. The LHC has also inspired works of fiction including novels, TV series, video games and films.

CERN employee Katherine McAlpine's "Large Hadron Rap"[114] surpassed 8 million YouTube views as of 2022.[115][116]

The band Les Horribles Cernettes was founded by women from CERN. The name was chosen so to have the same initials as the LHC.[117][118]

National Geographic Channel's World's Toughest Fixes, Season 2 (2010), Episode 6 "Atom Smasher" features the replacement of the last superconducting magnet section in the repair of the collider after the 2008 quench incident. The episode includes actual footage from the repair facility to the inside of the collider, and explanations of the function, engineering, and purpose of the LHC.[119]

The song "Munich" off of the 2012 studio album Scars & Stories by The Fray is inspired by the LHC. Lead singer Isaac Slade said in an interview with The Huffington Post, "There's this large particle collider out in Switzerland that is kind of helping scientists peel back the curtain on what creates gravity and mass. Some very big questions are being raised, even some things that Einstein proposed, that have just been accepted for decades are starting to be challenged. They're looking for the God Particle, basically, the particle that holds it all together. That song is really just about the mystery of why we're all here and what's holding it all together, you know?" [120]

The Large Hadron Collider was the focus of the 2012 student film Decay, with the movie being filmed on location in CERN's maintenance tunnels.[121]

الخيال

The novel Angels & Demons, by Dan Brown, involves antimatter created at the LHC to be used in a weapon against the Vatican. In response, CERN published a "Fact or Fiction?" page discussing the accuracy of the book's portrayal of the LHC, CERN, and particle physics in general.[122] The movie version of the book has footage filmed on-site at one of the experiments at the LHC; the director, Ron Howard, met with CERN experts in an effort to make the science in the story more accurate.[123]

The novel FlashForward, by Robert J. Sawyer, involves the search for the Higgs boson at the LHC. CERN published a "Science and Fiction" page interviewing Sawyer and physicists about the book and the TV series based on it.[124]

انظر أيضاً

- List of accelerators in particle physics

- Accelerator projects

- تجربة أطلس

- إشعاع هوكنگ

المصادر

- ^ "مصادم الهدرونات الكبير". ويكيبيديا. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- ^ Achenbach, Joel (2008-03-01). "The God Particle". National Geographic Magazine. National Geographic Society. ISSN 0027-9358. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ^ "LHC synchronization test successful". CERN bulletin.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (29 July 2008). "Let the Proton Smashing Begin. (The Rap Is Already Written.)". The New York Times.

- ^ CERN press release, 7 August 2008

- ^ "Large Hadron Collider to be launched Oct. 21 - Russian scientist". RIA Novosti.

- ^ "LHCb – Large Hadron Collider beauty experiment". lhcb-public.web.cern.ch.

- ^ Street, J.; Stevenson, E. (1937). "New Evidence for the Existence of a Particle of Mass Intermediate Between the Proton and Electron". Physical Review. 52 (9): 1003. Bibcode:1937PhRv...52.1003S. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.52.1003. S2CID 1378839.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةTheLHC - ^ "The Physics". ATLAS Experiment at CERN. 26 March 2015.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (15 May 2007). "CERN – Large Hadron Collider – Particle Physics – A Giant Takes On Physics' Biggest Questions". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ Giudice, G. F. (2010). A Zeptospace Odyssey: A Journey Into the Physics of the LHC. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958191-7. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ^ Brian Greene (11 September 2008). "The Origins of the Universe: A Crash Course". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ^ "... in the public presentations of the aspiration of particle physics we hear too often that the goal of the LHC or a linear collider is to check off the last missing particle of the Standard Model, this year's Holy Grail of particle physics, the Higgs boson. The truth is much less boring than that! What we're trying to accomplish is much more exciting, and asking what the world would have been like without the Higgs mechanism is a way of getting at that excitement." – Chris Quigg (2005). "Nature's Greatest Puzzles". Econf C. 040802 (1). arXiv:hep-ph/0502070. Bibcode:2005hep.ph....2070Q.

- ^ "Why the LHC". CERN. 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- ^ "Accordingly, in common with many of my colleagues, I think it highly likely that both the Higgs boson and other new phenomena will be found with the LHC."..."This mass threshold means, among other things, that something new – either a Higgs boson or other novel phenomena – is to be found when the LHC turns the thought experiment into a real one."Chris Quigg (February 2008). "The coming revolutions in particle physics". Scientific American. 298 (2): 38–45. Bibcode:2008SciAm.298b..46Q. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0208-46. OSTI 987233. PMID 18376670.

- ^ Shaaban Khalil (2003). "Search for supersymmetry at LHC". Contemporary Physics. 44 (3): 193–201. Bibcode:2003ConPh..44..193K. doi:10.1080/0010751031000077378. S2CID 121063627.

- ^ Alexander Belyaev (2009). "Supersymmetry status and phenomenology at the Large Hadron Collider". Pramana. 72 (1): 143–160. Bibcode:2009Prama..72..143B. doi:10.1007/s12043-009-0012-0. S2CID 122457391.

- ^ Anil Ananthaswamy (11 November 2009). "In SUSY we trust: What the LHC is really looking for". New Scientist.

- ^ Lisa Randall (2002). "Extra Dimensions and Warped Geometries" (PDF). Science. 296 (5572): 1422–1427. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1422R. doi:10.1126/science.1072567. PMID 12029124. S2CID 13882282. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ^ Panagiota Kanti (2009). "Black Holes at the Large Hadron Collider". Physics of Black Holes. Lecture Notes in Physics. Vol. 769. pp. 387–423. arXiv:0802.2218. Bibcode:2009LNP...769..387K. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-88460-6_10. ISBN 978-3-540-88459-0. S2CID 17651318.

- ^ "Heavy ions and quark–gluon plasma". CERN. 18 July 2012.

- ^ "LHC experiments bring new insight into primordial universe". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 26 November 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ Aad, G.; et al. (ATLAS Collaboration) (2010). "Observation of a Centrality-Dependent Dijet Asymmetry in Lead–Lead Collisions at √sNN = 2.76 TeV with the ATLAS detector at the LHC". Physical Review Letters. 105 (25): 252303. arXiv:1011.6182. Bibcode:2010PhRvL.105y2303A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.252303. PMID 21231581.

- ^ Symmetry magazine, April 2005

- ^ "CERN - LEP: the Z factory".

- ^ "LHC Guide booklet" (PDF).

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةwwlhccg - ^ "First beam in the LHC – accelerating science". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 10 سبتمبر 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- ^ Paul Rincon (23 September 2008). "Collider halted until next year". BBC News. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- ^ "Large Hadron Collider – Purdue Particle Physics". Physics.purdue.edu. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ Hadron Collider.

- ^ "The LHC is back". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 20 November 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ أ ب "Two circulating beams bring first collisions in the LHC". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 23 November 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ أ ب "What is LHCb" (PDF). CERN FAQ. CERN Communication Group. January 2008. p. 44. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ Amina Khan (31 March 2010). "Large Hadron Collider rewards scientists watching at Caltech". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ M. Hogenboom (24 July 2013). "Ultra-rare decay confirmed in LHC". BBC. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةirfu1 - ^ "Challenges in accelerator physics". CERN. 14 January 1999. Archived from the original on 5 October 2006. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- ^ John Poole (2004). "Beam Parameters and Definitions" (PDF). LHC Design Report.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (2 September 2008). "Courts weigh doomsday claims". Cosmic Log. msnbc.com.

- ^ http://www.aps.org/units/dpf/governance/reports/upload/lhc_saftey_statement.pdf

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7626944.stm Hadron Collider halted for months

- ^ تعليق عمل المعجل التصادمي لمدة شهرين في سويسرا

- ^ "«مصادم هادرون الكبير» يعود الى الحياة «الخطرة»". جريدة الحياة. 2009-11-24. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- ^ http://press.web.cern.ch/press/PressReleases/Releases2009/PR16.09E.html

- ^ {

CERN (30 November 2009). "LHC sets new world record". Press release. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://press.web.cern.ch/press/PressReleases/Releases2009/PR18.09E.html. Retrieved on 2010-03-02. - ^ "Large Hadron Collider to come back online after break". BBC News. 19 December 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- ^ "LHC sees first stable-beam 3.5 TeV collisions of 2011". symmetry breaking. 13 March 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- ^ "LHC sets world record beam intensity". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 22 April 2011. Retrieved 2016-11-13.

- ^ أ ب "Densest Matter Created in Big-Bang Machine". nationalgeographic.com. 2011-05-26.

- ^ "LHC achieves 2011 data milestone". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 17 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

- ^ Anna Phan. "One Recorded Inverse Femtobarn!!!". Quantum Diaries.

- ^ أ ب Jonathan Amos (22 December 2011). "LHC reports discovery of its first new particle". BBC News.

- ^ "LHC physics data taking gets underway at new record collision energy of 8TeV". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 5 April 2012. Retrieved 2016-11-13.

- ^ "New results indicate that new particle is a Higgs boson". CERN. 14 March 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ أ ب Ghosh, Pallab (12 Nov 2012). "Popular physics theory running out of hiding places". BBC News. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "The first LHC protons run ends with new milestone". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 17 December 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBBC - ^ "First successful beam at record energy of 6.5 TeV". CERN. 10 April 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ O'Luanaigh, Cian (21 May 2015). "First images of collisions at 13 TeV". CERN.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:0 - ^ "A new energy frontier for heavy ions". Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةdesignlumireached - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة2016lumi - ^ أ ب "Record luminosity: well done LHC". 15 Nov 2017. Retrieved 2 Dec 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت "LHC Report: Another run is over and LS2 has just begun…". CERN.

- ^ "Large Hadron Collider restarts". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 22 April 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ نيويورك تايمز

- ^ رويترز

- ^ P. Rincon (17 May 2010). "LHC particle search 'nearing', says physicist". BBC News.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةfirst science 2009 - ^ V. Khachatryan et al. (CMS collaboration) (2010). "Transverse momentum and pseudorapidity distributions of charged hadrons in pp collisions at [[:قالب:Radical]] = 0.9 and 2.36 TeV". Journal of High Energy Physics. 2010 (2): 1–35. arXiv:1002.0621. Bibcode:2010JHEP...02..041K. doi:10.1007/JHEP02(2010)041.

{{cite journal}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ V. Khachatryan et al. (CMS collaboration) (2011). "Search for Microscopic Black Hole Signatures at the Large Hadron Collider". Physics Letters B. 697 (5): 434–453. arXiv:1012.3375. Bibcode:2011PhLB..697..434C. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2011.02.032.

- ^ V. Khachatryan et al. (CMS collaboration) (2011). "Search for Supersymmetry in pp Collisions at 7 TeV in Events with Jets and Missing Transverse Energy". Physics Letters B. 698 (3): 196–218. arXiv:1101.1628. Bibcode:2011PhLB..698..196C. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2011.03.021.

- ^ G. Aad et al. (ATLAS collaboration) (2011). "Search for supersymmetry using final states with one lepton, jets, and missing transverse momentum with the ATLAS detector in [[:قالب:Radical]] = 7 TeV pp". Physical Review Letters. 106 (13): 131802. arXiv:1102.2357. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.106m1802A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.131802. PMID 21517374.

{{cite journal}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ G. Aad et al. (ATLAS collaboration) (2011). "Search for squarks and gluinos using final states with jets and missing transverse momentum with the ATLAS detector in [[:قالب:Radical]] = 7 TeV proton–proton collisions". Physics Letters B. 701 (2): 186–203. arXiv:1102.5290. Bibcode:2011PhLB..701..186A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2011.05.061.

{{cite journal}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Chalmers, M. Reality check at the LHC, physicsworld.com, 18 January 2011

- ^ McAlpine, K. Will the LHC find supersymmetry? Archived 25 فبراير 2011 at the Wayback Machine, physicsworld.com, 22 February 2011

- ^ Geoff Brumfiel (2011). "Beautiful theory collides with smashing particle data". Nature. 471 (7336): 13–14. Bibcode:2011Natur.471...13B. doi:10.1038/471013a. PMID 21368793.

- ^ "LHC experiments present their latest results at Europhysics Conference on High Energy Physics". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 21 July 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ "LHC experiments present latest results at Mumbai conference". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 22 August 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Pallab Ghosh (22 August 2011). "Higgs boson range narrows at European collider". BBC News.

- ^ Pallab Ghosh (27 August 2011). "LHC results put supersymmetry theory 'on the spot'". BBC News.

- ^ "LHCb experiment sees Standard Model physics". Symmetry Magazine. SLAC/Fermilab. 29 August 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "ATLAS and CMS experiments present Higgs search status". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 13 December 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ "CERN experiments observe particle consistent with long-sought Higgs boson". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 4 يوليو 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ "Now confident: CERN physicists say new particle is Higgs boson (Update 3)". Phys Org. 14 March 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ LHCb Collaboration (7 January 2013). "First Evidence for the Decay ". Physical Review Letters. 110 (2): 021801. arXiv:1211.2674. Bibcode:2013PhRvL.110b1801A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.021801. PMID 23383888. S2CID 13103388.

- ^ CMS collaboration (5 September 2013). "Measurement of the Branching Fraction and Search for with the CMS Experiment". Physical Review Letters. 111 (10): 101804. arXiv:1307.5025. Bibcode:2013PhRvL.111j1804C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.101804. PMID 25166654.

- ^ "Hints of New Physics Detected in the LHC?". 10 May 2017.

- ^ New subatomic particles predicted by Canadians found at CERN, 19 November 2014

- ^ "LHCb experiment observes two new baryon particles never seen before". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 19 November 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- ^ O'Luanaigh, Cian (9 April 2014). "LHCb confirms existence of exotic hadrons". CERN. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Aaij, R.; et al. (LHCb collaboration) (4 June 2014). "Observation of the resonant character of the Z(4430)− state". Physical Review Letters. 112 (21): 222002. arXiv:1404.1903. Bibcode:2014PhRvL.112v2002A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.222002. PMID 24949760.

- ^ Aaij, R.; et al. (LHCb collaboration) (12 August 2015). "Observation of J/ψp resonances consistent with pentaquark states in Λ0b→J/ψK−p decays". Physical Review Letters. 115 (7): 072001. arXiv:1507.03414. Bibcode:2015PhRvL.115g2001A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.072001. PMID 26317714.

- ^ "CERN's LHCb experiment reports observation of exotic pentaquark particles". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (1 July 2015). "Large Hadron Collider discovers new pentaquark particle". BBC News. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^ Aaij, R.; et al. (LHCb collaboration) (2017). "Observation of J/ψφ structures consistent with exotic states from amplitude analysis of B+→J/ψφK+ decays". Physical Review Letters. 118 (2): 022003. arXiv:1606.07895. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.118b2003A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.022003. PMID 28128595. S2CID 206284149.

- ^ Aaij, R.; et al. (LHCb collaboration) (2017). "Amplitude analysis of B+→J/ψφK+ decays". Physical Review D. 95 (1): 012002. arXiv:1606.07898. Bibcode:2017PhRvD..95a2002A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.95.012002. S2CID 73689011.

- ^ "ATLAS releases first measurement of the W mass using LHC data". 13 December 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (15 December 2015). "Physicists in Europe Find Tantalizing Hints of a Mysterious New Particle". New York Times. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ CMS Collaboration (15 December 2015). "Search for new physics in high mass diphoton events in proton–proton collisions at 13 TeV". Compact Muon Solenoid. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ ATLAS Collaboration (15 December 2015). "Search for resonances decaying to photon pairs in 3.2 fb−1 of pp collisions at √s = 13 TeV with the ATLAS detector" (PDF). Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ CMS Collaboration. "CMS Physics Analysis Summary" (PDF). CERN. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (5 August 2016). "The Particle That Wasn't". New York Times. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ^ "Chicago sees floods of LHC data and new results at the ICHEP 2016 conference". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 5 August 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "LHC experiments delve deeper into precision". Media and Press Relations (Press release). CERN. 11 July 2017. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ "59 new hadrons and counting". CERN. 3 March 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Large Hadron Collider project discovers three new exotic particles | E&T Magazine". Eandt.theiet.org. 2022-07-05. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- ^ "A new schedule for the LHC and its successor". 13 December 2019.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةautogenerated1 - ^ "Future Circular Collider: The Race To Build the World's Most Powerful Particle Collider". 7 April 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ Katherine McAlpine (28 July 2008). "Large Hadron Rap". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-10-30. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ Roger Highfield (6 September 2008). "Rap about world's largest science experiment becomes YouTube hit". Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- ^ Jennifer Bogo (1 August 2008). "Large Hadron Collider rap teaches particle physics in 4 minutes". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- ^ Malcolm W Brown (29 December 1998). "Physicists Discover Another Unifying Force: Doo-Wop" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ Heather McCabe (10 February 1999). "Grrl Geeks Rock Out" (PDF). Wired News. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ "Atom Smashers". World's Toughest Fixes. National Geographic Channel. No. 6, season 2.

- ^ Ragogna, Mike (20 January 2012). "The Wayman Tisdale Story and Scars & Stories: Conversations with Director Brian Schodorf and The Fray's Isaac Slade". Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Boyle, Rebecca (31 October 2012). "Large Hadron Collider Unleashes Rampaging Zombies". Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Taylor, Allen (2011). "Angels and Demons". New Scientist. CERN. 214 (2871): 31. Bibcode:2012NewSc.214R..31T. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(12)61690-X. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ Ceri Perkins (2 June 2008). "ATLAS gets the Hollywood treatment". ATLAS e-News. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ "FlashForward". CERN. September 2009. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

وصلات خارجية

- الموقع الرسمي للمصادم

- صفحة المصادم على موقع CERN

- الجدول الزمني للمصادم

- جولة افتراضية في المصادم

- حول المصادم، بالعربية

- تابع الإختبارات مباشرة من غرفة المراقبة في المصادم

| حلقات التخزين المتقاطعة | سرن، 1971-1984 |

|---|---|

| سنكروترون الپروتونات الفائق | سرن، 1981-1984 |

| إيزابل | BNL، ألغي في 1983 |

| تڤاترون | فرميلاب، 1987-الحاضر |

| مصادم الأيونات الثقيلة النسبوي | BNL، 2000–الحاضر |

| المصادم الهائل فائق التوصيل | ألغي في 1993 |

| مصادم الهدرونات الكبير | سرن، 2009- |

| مصادم الهدرونات الكبير الهائل | مقترح، سرن، 2019– |

| مصادم الهدرونات الكبير جداً | نظري |

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 errors: URL–wikilink conflict

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- مصادم الهدرونات الكبير

- مباني ومنشآت في آين

- مباني ومنشآت في كانتون جنيڤ

- CERN accelerators

- E-Science

- International science experiments

- Laboratories in France

- Laboratories in Switzerland

- منشآت فيزياء الجسيمات

- Physics beyond the Standard Model

- Underground laboratories

- CERN facilities

- Buildings and structures completed in 2008