علم النقوش

علم دراسة النقوش أو إپيگرافيا (Epigraphy ؛ من يونانية قديمة ἐπιγραφή (epigraphḗ)، وتعني "inscription"، من إپي-گرافه، حرفياً "عن-الكتابة"، "نقش"[1]) ؛ إنگليزية: Epigraphy) هو علم دراسة النقوش والكتابات القديمة، ككتابة. it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the writing and the writers. Specifically excluded from epigraphy are the historical significance of an epigraph as a document and the artistic value of a literary composition. A person using the methods of epigraphy is called an epigrapher or epigraphist. For example, the Behistun inscription is an official document of the Achaemenid Empire engraved on native rock at a location in Iran. Epigraphists are responsible for reconstructing, translating, and dating the trilingual inscription and finding any relevant circumstances. It is the work of historians, however, to determine and interpret the events recorded by the inscription as document. Often, epigraphy and history are competences practised by the same person. Epigraphy is a primary tool of archaeology when dealing with literate cultures.[2] The US Library of Congress classifies epigraphy as one of the auxiliary sciences of history.[3] Epigraphy also helps identify a forgery:[4] epigraphic evidence formed part of the discussion concerning the James Ossuary.[5][6]

An epigraph (not to be confused with epigram) is any sort of text, from a single grapheme (such as marks on a pot that abbreviate the name of the merchant who shipped commodities in the pot) to a lengthy document (such as a treatise, a work of literature, or a hagiographic inscription). Epigraphy overlaps other competences such as numismatics or palaeography. When compared to books, most inscriptions are short. The media and the forms of the graphemes are diverse: engravings in stone or metal, scratches on rock, impressions in wax, embossing on cast metal, cameo or intaglio on precious stones, painting on ceramic or in fresco. Typically the material is durable, but the durability might be an accident of circumstance, such as the baking of a clay tablet in a conflagration.

The character of the writing, the subject of epigraphy, is a matter quite separate from the nature of the text, which is studied in itself. Texts inscribed in stone are usually for public view and so they are essentially different from the written texts of each culture. Not all inscribed texts are public, however: in Mycenaean Greece the deciphered texts of "Linear B" were revealed to be largely used for economic and administrative record keeping. Informal inscribed texts are "graffiti" in its original sense.

The study of ideographic inscriptions, that is inscriptions representing an idea or concept, may also be called ideography. The German equivalent Sinnbildforschung was a scientific discipline in the Third Reich, but was later dismissed as being highly ideological.[7] Epigraphic research overlaps with the study of petroglyphs, which deals with specimens of pictographic, ideographic and logographic writing. The study of ancient handwriting, usually in ink, is a separate field, palaeography.[8] Epigraphy also differs from iconography, as it confines itself to meaningful symbols containing messages, rather than dealing with images.

التاريخ

علم دراسة النقوش يتطور قدماً منذ العصور الوسطى. فمبادئ الإپيگرافيا تختلف من حضارة إلى أخرى، فمؤرخو العربية ركزوا على نقوش الشرق الأدنى القديم المختلفة، المرؤخون الصينيون ركزوا على نقوش الصينية القديمة، بينما ركز المؤرخون الاوروبيون على النقوش اللاتينية في البداية. إسهامات جديرة بالإفراد قام بها علماء الخطاطة مثل ذو النون المصري (786-859)، أبو الحسن الهمداني (ت. 945), ابن وحشية (القرن 10)، شن كوو (1031-1095)، گيورگ فابريسيوس (1516–1571)، أوگوست ڤيلهلم تسومپت (1815–1877)، تيودور مومسن (1817–1903)، إميل هوبنر (1834–1901)، فرانز كومون (1868–1947) ولويس روبرت (1904–1985).

علم النقوش

هي كتابات قديمة تقدم لعلماء الآثار والتاريخ دليلاً موثقاً يمكّنهم من فهم المعتقدات والأفكار التي توصلت إليها أقوام عاشت قبل آلاف السنين، كما أنه بتوافر النقوش أصبح بالإمكان تحديد التاريخ الدقيق للزمن الذي ترك فيه القدماء كتاباتهم على الأبنية أو على الألواح والرقم والقطع التي تحمل نصوص الرسائل أو قوائم أسماء الملوك وسوى ذلك من موضوعات مدوًّنة. غير أن هذا الدليل لا يمكن أن يستعمل إلا في التعامل مع خمسة آلاف سنة الأخيرة من تاريخ البشرية، فقبل ذلك عاش الإنسان مئات الآلاف من السنين في عصور ما قبل التاريخ التي لم يتوصل فيها إلى التدوين، ومن ثم لا سبيل هناك إلى دراسة تاريخه فيها سوى من المخلفات المادية وما تدل عليه.

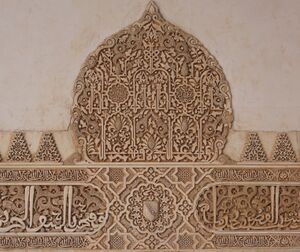

يتناول علم النقوش (أبيغرافيا) Epigraphy دراسة النقوش المدونة على الحجر أو المعدن وكذلك المحفورة على الفخار أو الآجر. ولذلك فإن هذا العلم لا يشمل الكتابات المطلية على الفخار أو الخشب أو على لفائف البردي. ويعود تاريخ النقوش إلى أول اختراع الكتابة، إذ إنها مثلت النصوص الأولى المحفورة على الرقم الطينية في بلاد الرافدين وعلى الحجر في بلاد وادي النيل في أواخر الألف الرابع قبل الميلاد. استمرت النقوش في التطور لتنتقل من النصوص المقطعية إلى الأبجدية. وقد دُوِّنت فيها اللغات القديمة التي استعملت الكتابة المقطعية مثل: السومرية والأكادية والعيلامية والمصرية القديمة والحثية والحورية والأورارطية، واللغات التي استعملت الكتابة الأبجدية مثل الكنعانية والآرامية والعربية الجنوبية والعربية الشمالية والإغريقية واللاتينية.

يمكن تقسيم أنواع النقوش بحسب المواد التي حُفرت عليها، وهذه المواد هي الطين والحجر والمعدن. وكان الطين ينقش ويترك ليجف أو يشوى بالنار ويتحول إلى فخار وقد يكون هذا الطين بشكل ألواح أو آجر أو أوعية وأوانٍ فخارية متنوعة. أما الحجر فإما أن يكون بشكل ألواح مستعملة في البناء أو مسلات أو تماثيل أو توابيت أو أحجار بتكويناتها الطبيعية. وكانت المعادن المستعملة في تدوين النقوش تشمل البرونز والحديد والذهب والفضة. أما الأشكال التي ظهرت بها تلك المعادن فقد شملت الأدوات والأسلحة والأثاث والتماثيل والألواح والحلي والنقود.[9]

إن أقدم النقوش المدونة هي المسمارية[ر] التي دُونِّت بها اللغتان السومرية والأكادية فضلاً عن لغات أخرى مثل: العيلامية والحثية والحورية والأبجدية الأغاريتية. وتنتشر هذه النقوش في بلاد الرافدين وبلاد الشام وبلاد فارس وآسيا الصغرى. وفي مصر وجدت النقوش الهيروغليفية التي استُعملت للنصوص التذكارية على الحجر والجدران. ومن أشهر النقوش الإغريقية قوائم ضرائب العصبة الأثينية، واللائحة القانونية في كريت، ومرسوم تحديد الأسعار القصوى للمواد الغذائية. أما النقوش اللاتينية فمن أهمها القوانين ونقوش فاكتي Facti، وهي قائمة بأسماء القضاة الرئيسيين.

انتشرت النصوص المدونة باللغة العربية الجنوبية - وجميعها نقوش على المعدن أو الحجر- من مواقع مختلفة من اليمن وشبه الجزيرة العربية، وكانت أغلب النقوش المكتشفة في مراحلها المبكرة تدون من اليمين إلى اليسار وبالعكس، ويرجح أن يعود تاريخها إلى القرن التاسع أو الثامن قبل الميلاد، أما موضوعاتها فهي: نذرية، تذكارية، تاريخية،جنائزية، وأوامر لضبط النظام. وتكشف الأبجدية العربية الجنوبية التي دونت بها تلك النقوش تأثيرات الأبجدية السينائية. وقد امتد تأثير الأبجدية العربية الجنوبية إلى شمالي الجزيرة العربية حيث دَوِّنت النقوش العربية الشمالية التي تعود إليها أصول اللغة العربية الفصحى.

تشمل النقوش العربية الشمالية نقوش منطقة الصفا البركانية في حوران التي يعود تاريخها إلى 100م تقريباً، وكذلك النقوش الديدانية واللحيانية المكتشفة في العُلى شمالي الحجاز، ويعود تاريخها إلى ما بين القرنين السابع والثالث قبل الميلاد. أما النقوش الثمودية - وخصوصاً المكتشفة في الحجر وتيماء - فتعود إلى ما بين القرنين الخامس قبل الميلاد والرابع الميلادي.

لم تكن جميع النقوش القديمة أحادية اللغة وإنما وجدت نقوش ثنائية وثلاثية اللغة. ومن النقوش ثنائية اللغة تلك السومرية - الأكادية التي اكتُشف العديد منها في مواقع المشرق العربي، والآشورية - الآرامية مثل النقش المدون على تمثال «هدد- يسعي» الذي اكتُشف في تل الفخيرية في شمال - شرقي سورية. أما من النقوش الإغريقية والرومانية الثنائية اللغة فقد اشتهر نقش السيرة الذاتية لأغسطس Augustus. وقد كان لبعض النقوش الثلاثية اللغة أو الخط دور مهم في حل رموز الكتابات القديمة مثل نقش رشيد الذي نقش بالخطوط الهيروغليفية والديموطيقية والإغريقية القديمة، ونقش بهستون Behistun المدون باللغات الأكادية والعيلامية والفارسية القديمة، ومثله نقوش العاصمة الأخمينية برسيبولس Persepolis.

وعلى الرغم من أن معظم النقوش القديمة قد حُلَّت رموزها وأصبحت ذات فائدة كبيرة في دراسة الحضارات القديمة ومعرفة أحوالها السياسية والاجتماعية والدينية والاقتصادية، فإنه لم تزل هناك نقوش غير قابلة للقراءة ولم تُحلّ رموزها حتى اليوم، ومنها تلك المدونة بالخط أ (Linear A) في جزيرة كريت، ويعود تاريخها إلى النصف الأول من الألف الثاني قبل الميلاد. وكذلك لم يزل الغموض يكتنف النقوش الأتروسكانية المكتشفة في وسط إيطاليا بالرغم من اكتشاف نحو عشرة آلاف نقش منها، ويقدر تاريخها نحو منتصف الألف الأول قبل الميلاد. ومن نقوش الحضارات القديمة التي لم تحل رموزها حتى اليوم نقوش حضارة وادي السند القديمة التي يعود تاريخها إلى 2000 ق.م تقريباً. وفي أمريكا الوسطى توجد نقوش من حضارة المايا تصعب قراءتها حتى الوقت الحاضر.

Latin inscriptions

Latin inscriptions may be classified on much the same lines as Greek; but certain broad distinctions may be drawn at the outset. They are generally more standardised as to form and as to content, not only in Rome and Italy, but also throughout the provinces of the Roman Empire. One of the chief difficulties in deciphering Latin Inscriptions lies in the very extensive use of initials and abbreviations. These are of great number and variety, and while some of them can be easily interpreted as belonging to well-known formulae, others offer considerable difficulty, especially to the inexperienced student.[10] Often the same initial may have many different meanings according to the context. Some common formulae such as V.S.L.M. (votum solvit libens merito), or H.M.H.N.S. (hoc monumentum heredem non sequetur) offer little difficulty, but there are many which are not so obvious and leave room for conjecture. Often the only way to determine the meaning is to search through a list of initials, such as those given by modern Latin epigraphists, until a formula is found which fits the context.

Most of what has been said about Greek inscriptions applies to Roman also. The commonest materials in this case also are stone, marble and bronze; but a more extensive use is made of stamped bricks and tiles, which are often of historical value as identifying and dating a building or other construction. The same applies to leaden water pipes which frequently bear dates and names of officials. Terracotta lamps also frequently have their makers' names and other information stamped upon them. Arms, and especially shields, sometimes bear the name and corps of their owners. Leaden discs were also used to serve the same purpose as modern identification discs. Inscriptions are also found on sling bullets – Roman as well as Greek; there are also numerous classes of tesserae or tickets of admission to theatres or other shows.

As regards the contents of inscriptions, there must evidently be a considerable difference between records of a number of independent city states and an empire including almost all the civilised world; but municipalities maintained much of their independent traditions in Roman times, and consequently their inscriptions often follow the old formulas.

The classification of Roman inscriptions may, therefore, follow the same lines as the Greek, except that certain categories are absent, and that some others, not found in Greek, are of considerable importance.

Religious

Dedications and foundations of temples, etc.

These are very numerous; and the custom of placing the name of the dedicator in a conspicuous place on the building was prevalent, especially in the case of dedications by emperors or officials, or by public bodies. Restoration or repair was often recorded in the same manner. In the case of small objects the dedication is usually simple in form; it usually contains the name of the god or other recipient and of the donor, and a common formula is D.D. (dedit, donavit) often with additions such as L.M. (libens merito). Such dedications are often the result of a vow, and V.S. (votum solvit) is therefore often added. Bequests made under the wills of rich citizens are frequently recorded by inscriptions; these might either be for religious or for social purposes.

Priests and officials

A priesthood was frequently a political office and consequently is mentioned along with political honours in the list of a man's distinctions. The priesthoods that a man had held are usually mentioned first in inscriptions before his civil offices and distinctions. Religious offices, as well as civil, were restricted to certain classes, the highest to those of senatorial rank, the next to those of equestrian status; many minor offices, both in Rome and in the provinces, are enumerated in their due order.

Regulations as to religion and cult

Among the most interesting of these is the ancient song and accompanying dance performed by the priests known as the Arval Brothers. This is, however, not in the form of a ritual prescription, but a detailed record of the due performance of the rite. An important class of documents is the series of calendars that have been found in Rome and in the various Italian towns. These give notice of religious festivals and anniversaries, and also of the days available for various purposes.

Colleges

The various colleges for religious purposes were very numerous. Many of them, both in Rome and Italy, and in provincial municipalities, were of the nature of priesthoods. Some were regarded as offices of high distinction and were open only to men of senatorial rank; among these were the Augurs, the Fetiales, the Salii; also the Sodales Divorum Augustorum in imperial times. The records of these colleges sometimes give no information beyond the names of members, but these are often of considerable interest. Haruspices and Luperci were of equestrian rank.

Political and social

Codes of law and regulations

Our information as to these is not mainly drawn from inscriptions and, therefore, they need not here be considered. On the other hand, the word lex (law) is usually applied to all decrees of the senate or other bodies, whether of legislative or of administrative character. It is therefore, best to consider all together under the heading of public decrees.

Laws and plebiscites, senatus consulta, decrees of magistrates or later of emperors

A certain number of these dating from republican times are of considerable interest. One of the earliest relates to the prohibition of bacchanalian orgies in Italy; it takes the form of a message from the magistrates, stating the authority on which they acted. Laws all follow a fixed formula, according to the body which has passed them. First there is a statement that the legislative body was consulted by the appropriate magistrate in due form; then follows the text of the law; and finally the sanction, the statement that the law was passed. In decrees of the senate the formula differs somewhat. They begin with a preamble giving the names of the consulting magistrates, the place and conditions of the meeting; then comes the subject submitted for decision, ending with the formula QDERFP (quid de ea re fieri placeret); then comes the decision of the senate, opening with DERIC (de ea re ita censuerunt). C. is added at the end, to indicate that the decree was passed. In imperial times, the emperor sometimes addressed a speech to the senate, advising them to pass certain resolutions, or else, especially in later times, gave orders or instructions directly, either on his own initiative or in response to questions or references. The number and variety of such orders is such that no classification of them can be given here. One of the most famous is the edict of Diocletian, fixing the prices of all commodities. Copies of this in Greek as well as in Latin have been found in various parts of the Roman Empire.[12]

Records of buildings, etc.

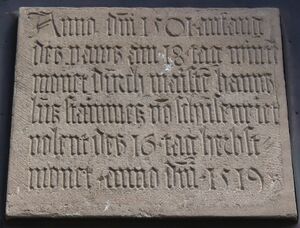

A very large number of inscriptions record the construction or repair of public buildings by private individuals, by magistrates, Roman or provincial, and by emperors. In addition to the dedication of temples, we find inscriptions recording the construction of aqueducts, roads, especially on milestones, baths, basilicas, porticos and many other works of public utility. In inscriptions of early period often nothing is given but the name of the person who built or restored the edifice and a statement that he had done so. But later it was usual to give more detail as to the motive of the building, the name of the emperor or a magistrate giving the date, the authority for the building and the names and distinctions of the builders; then follows a description of the building, the source of the expenditure (e.g., S.P., sua pecunia) and finally the appropriate verb for the work done, whether building, restoring, enlarging or otherwise improving. Other details are sometimes added, such as the name of the man under whose direction the work was done.

Military documents

These vary greatly in content, and are among the most important documents concerning the administration of the Roman Empire. "They are numerous and of all sorts – tombstones of every degree, lists of soldiers' burial clubs, certificates of discharge from service, schedules of time-expired men, dedications of altars, records of building or of engineering works accomplished. The facts directly commemorated are rarely important."[13] But when the information from hundreds of such inscriptions is collected together, "you can trace the whole policy of the Imperial Government in the matter of recruiting, to what extent and till what date legionaries were raised in Italy; what contingents for various branches of the service were drawn from the provinces, and which provinces provided most; how far provincials garrisoned their own countries, and which of them, like the British recruits, were sent as a measure of precaution to serve elsewhere; or, finally, at what epoch the empire grew weak enough to require the enlistment of barbarians from beyond its frontiers."[13]

Treaties and agreements

There were many treaties between Rome and other states in republican times; but we do not, as a rule, owe our knowledge of these to inscriptions, which are very rare in this earlier period. In imperial times, to which most Latin inscriptions belong, international relations were subject to the universal domination of Rome, and consequently the documents relating to them are concerned with reference to the central authority, and often take the form of orders from the emperor.

Proxeny

This custom belonged to Greece. What most nearly corresponded to it in Roman times was the adoption of some distinguished Roman as its patron, by a city or state. The relation was then recorded, usually on a bronze tablet placed in some conspicuous position in the town concerned. The patron probably also kept a copy in his house, or had a portable tablet which would ensure his recognition and reception.

Honorary

Honorary inscriptions are extremely common in all parts of the Roman world. Sometimes they are placed on the bases of statues, sometimes in documents set up to record some particular benefaction or the construction of some public work. The offices held by the person commemorated, and the distinctions conferred upon him are enumerated in a regularly established order (cursus honorum), either beginning with the lower and proceeding step by step to the higher, or in reverse order with the highest first. Religious and priestly offices are usually mentioned before civil and political ones. These might be exercised either in Rome itself, or in the various municipalities of the empire. There was also a distinction drawn between offices that might be held only by persons of senatorial rank, those that were assigned to persons of equestrian rank, and those of a less distinguished kind. It follows that when only a portion of an inscription has been found, it is often possible to restore the whole in accordance with the accepted order.

Signatures of artists

When these are attached to statues, it is sometimes doubtful whether the name is that of the man who actually made the statue, or of the master whose work it reproduces. Thus there are two well-known copies of a statue of Hercules by Lysippus, of which one is said to be the work of Lysippus, and the other states that it was made by Glycon (see images). Another kind of artist's or artificer's signature that is commoner in Roman times is to be found in the signatures of potters upon lamps and various kinds of vessels; they are usually impressed on the mould and stand out in relief on the terracotta or other material. These are of interest as giving much information as to the commercial spread of various kinds of handicrafts, and also as to the conditions under which they were manufactured.

Historical records

Many of these inscriptions might well be assigned to one of the categories already considered. But there are some which were expressly made to commemorate an important event, or to preserve a record. Among the most interesting is the inscription of the Columna Rostrata in Rome, which records the great naval victory of Gaius Duilius over the Carthaginians; this, however, is not the original, but a later and somewhat modified version. A document of high importance is a summary of the life and achievements of Augustus, already mentioned, and known as the Monumentum Ancyranum. The various sets of Fasti constituted a record of the names of consuls, and other magistrates or high officials, and also of the triumphs accorded to conquering generals.

Inscriptions on tombs

These are probably the most numerous of all classes of inscriptions; and though many of them are of no great individual interest, they convey, when taken collectively, much valuable information as to the distribution and transference of population, as to trades and professions, as to health and longevity, and as to many other conditions of ancient life. The most interesting early series is that on the tombs of the Scipios at Rome, recording, mostly in Saturnian Metre, the exploits and distinctions of the various members of that family.[14]

About the end of the republic and the beginning of the empire, it became customary to head a tombstone with the letters D.M. or D.M.S. (Dis Manibus sacrum), thus consecrating the tomb to the deceased as having become members of the body of ghosts or spirits of the dead. These are followed by the name of the deceased, usually with his father's name and his tribe, by his honours and distinctions, sometimes by a record of his age. The inscription often concludes with H.I. (Hic iacet), or some similar formula, and also, frequently, with a statement of boundaries and a prohibition of violation or further use – for instance, H.M.H.N.S. (hoc monumentum heredem non sequetur, this monument is not to pass to the heir). The person who has erected the monument and his relation to the deceased are often stated; or if a man has prepared the tomb in his lifetime, this also may be stated, V.S.F. (vivus sibi fecit). But there is an immense variety in the information that either a man himself or his friend may wish to record.[14]

Milestones and boundaries

Milliarium (milestones) have already been referred to, and may be regarded as records of the building of roads. Boundary stones (termini) are frequently found, both of public and private property. A well-known instance is offered by those set up by the commissioners called III. viri A.I.A. (agris iudicandis adsignandis) in the time of the Gracchi.[15]

Sanskrit inscriptions

انظر أيضاً

حقول بحث ذات صلة

أنواع النقوش

نقوش هامة

الهامش

- ^ "Epigraph". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Bozia, Eleni; Barmpoutis, Angelos; Wagman, Robert S. (2014). "OPEN-ACCESS EPIGRAPHY. Electronic Dissemination of 3D-digitized. Archaeological Material" (PDF). Hypotheses.org: 12. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ Drake, Miriam A. (2003). Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science. Dekker Encyclopedias Series. Vol. 3. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8247-2079-2.

- ^ Orlandi, Silvia; Caldelli, Maria Letizia; Gregori, Gian Luca (November 2014). Bruun, Christer; Edmondson, Jonathan (eds.). "Forgeries and Fakes". The Oxford Handbook of Roman Epigraphy. Oxford Handbooks. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195336467.013.003. ISBN 9780195336467.

- ^ Silberman, Neil Asher; Goren, Yuval (September–October 2003). "Faking Biblical History: How wishful thinking and technology fooled some scholars – and made fools out of others". Archaeology. Vol. 56, no. 5. Archaeological Institute of America. pp. 20–29. JSTOR 41658744. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ^ Shanks, Hershel. "Related Coverage on the James Ossuary and Forgery Trial". Biblical Archaeology Review. Archived from the original on 2011-09-07. Retrieved 2012-02-27.

- ^ Mees, Bernard Thomas, The Science of the Swastika, Budapest / New York 2008.

- ^ Brown, Julian. "What is Palaeography?" (PDF). UMassAmherst. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ نائل حنون. "النقوش (علم ـ)". الموسوعة العربية.

- ^ A mere list of such initials and abbreviations occupies 68 pages in René Cagnat's Cours d'épigraphie Latine (repr. 1923). A selection is included in Wikipedia's "List of classical abbreviations".

- ^ It reads: Victo(riae) Fl(avius) P/rimus cur(ator) / tur(mae) Maxi/mini.

- ^ Cf. E.R. Graser (1940). T. Frank (ed.). An Economic Survey of Ancient Rome Volume V: Rome and Italy of the Empire. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press – esp. "A text and translation of the Edict of Diocletian".

- ^ أ ب Francis Haverfield, "Roman Authority" in S. R. Driver, D. G. Hogarth, F. L. Griffith, et al. Authority and Archaeology, Sacred and Profane: Essays on the Relation of Monuments to Biblical and Classical Literature, Ulan Press (repr. 2012), p. 314.

- ^ أ ب Cf. Edward Courtney (1995). MUSA Lapidaria: A Selection of Latin Verse Inscriptions. Atlanta: Scholars Press.

- ^ Cf. Arthur E. Gordon, Latin Epigraphy, University of California Press, 1983, Introd., pp. 3–6.

- ^ أ ب ت Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: ca. 150 BCE – 100 CE. BRILL Academic. p. 260. ISBN 978-90-04-15537-4. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ Court, Christopher (1996). "The Spread of Brahmi Script into Southeast Asia". In Daniels, Peter T. (ed.). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ Masica, Colin P. (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

وصلات خارجية

- Bodel, John (1997–2009). "U.S. Epigraphy Project" (html). Brown University. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Centre d'études épigraphiques et numismatiques de la faculté de Philosophie de l'Université de Beograd. "Inscriptions de la Mésie Supérieure" (in French). Retrieved 22 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - "Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents". Oxford: Oxford University. 1995–2009. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Clauss, Manfred. "Epigraphik-Datenbank Clauss-Slaby". Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- "EAGLE: Electronic Archive of Greek and Latin Epigraphy" (in Italian). Federazione Internazionale di Banche dati Epigrafiche presso il Centro Linceo Interdisciplinare "Beniamino Segre" - Roma. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)- "Epigraphische Datenbank Heidelberg". 1986–2007. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - International Federation of Epigraphic Databases. "EDR Epigraphic Database Roma" (in Italian). Association Internationale d'Épigraphie Grecque et Latine - AIEGL. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - International Federation of Epigraphic Databases. "Epigraphic Database Bari: Documenti epigrafici romani di committenza cristiana - Secoli III - VIII" (in Italian). Association Internationale d'Épigraphie Grecque et Latine - AIEGL. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

- "Epigraphische Datenbank Heidelberg". 1986–2007. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- Greek Epigraphy Project, Cornell University (2009). "Searchable Greek Inscriptions". Packard Humanities Institute. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - The Institute for Ancient History (1993–2009). "Epigraphic database for ancient Asia Minor". Universität Hamburg. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Reynolds, Joyce; Roueché, Charlotte; Bodard, Gabriel (2007). "Inscriptions of Aphrodisias (IAph2007)". London: King's College. ISBN 978-1-897747-19-3.

- "The American Society for Greek and Latin Epigraphy (ASGLE)". Case Western Reserve University. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- "Ubi Erat Lupa" (in German). Universität Salzburg. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with broken excerpts

- CS1 maint: date format

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- تأريخ

- فروع علم الآثار

- Inscriptions

- علم الآثار