چغتاي (لغة)

| Chagatai | |

|---|---|

| چغتای Čaġatāy | |

Chagatai written in Nastaliq script (چغتای) | |

| المنطقة | Central Asia |

| منقرضة | Around 1921 |

Turkic

| |

الصيغ المبكرة | |

| Perso-Arabic script (Nastaliq) | |

| الوضع الرسمي | |

لغة رسمية في |

|

| أكواد اللغات | |

| ISO 639-2 | chg |

| ISO 639-2 | chg |

| ISO 639-3 | chg |

chg | |

| Glottolog | chag1247 |

Chagatai[أ] (چغتای, Čaġatāy), also known as Turki[ب][4] or Chagatay Turkic (Čaġatāy türkīsi),[3] is an extinct Turkic literary language that was once widely spoken in Central Asia and remained the shared literary language there until the early 20th century. It was used across a wide geographic area including parts of modern-day Uzbekistan, Xinjiang, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan.[5] Literary Chagatai is the predecessor of the modern Karluk branch of Turkic languages, which include Uzbek and Uyghur.[6] Turkmen, which is not within the Karluk branch but in the Oghuz branch of Turkic languages, was heavily influenced by Chagatai for centuries.[7]

Ali-Shir Nava'i was the greatest representative of Chagatai literature.[8]

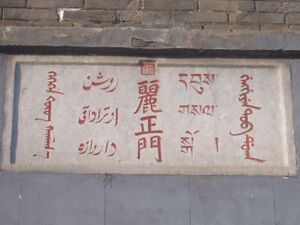

Lizheng gate in the Chengde Mountain Resort, the second column from left is Chagatai language written in Perso-Arabic Nastaʿlīq script. |

Chagatai literature is still studied in modern Uzbekistan, where the language is seen as the predecessor and the direct ancestor of modern Uzbek and the literature is regarded as part of the national heritage of Uzbekistan. In Turkey it is studied and regarded as part of the common, wider Turkic heritage.

أصل الاسم

The word Chagatai relates to the Chagatai Khanate (1225–1680s), a descendant empire of the Mongol Empire left to Genghis Khan's second son, Chagatai Khan.[9] Many of the Turkic peoples, who were the speakers of this language, claimed political descent from Chagatai Khanate.

As part of the preparation for the 1924 establishment of the Soviet Republic of Uzbekistan, Chagatai was officially renamed "Old Uzbek",[10][11][6][12][4] which Edward A. Allworth argued "badly distorted the literary history of the region" and was used to give authors such as Ali-Shir Nava'i an Uzbek identity.[13][14] It was also referred to as "Turki" or "Sart".[4] In China, it is sometimes called "ancient Uyghur".[15]

التاريخ

Chagatai is a Turkic language that was developed in the late 15th century.[6] It belongs to the Karluk branch of the Turkic language family. It is descended from Middle Turkic, which served as a lingua franca in Central Asia, with a strong infusion of Arabic and Persian words and turns of phrase.

Mehmet Fuat Köprülü divides Chagatay into the following periods:[16]

- Early Chagatay (13th–14th centuries)

- Pre-classical Chagatay (the first half of the 15th century)

- Classical Chagatay (the second half of the 15th century)

- Continuation of Classical Chagatay (16th century)

- Decline (17th–19th centuries)

The first period is a transitional phase characterized by the retention of archaic forms; the second phase starts with the publication of Ali-Shir Nava'i's first Divan and is the highpoint of Chagatai literature, followed by the third phase, which is characterized by two bifurcating developments. One is the preservation of the classical Chagatai language of Nava'i, the other trend is the increasing influence of the dialects of the local spoken languages.

Influence on later Turkic languages

Uzbek and Uyghur are the two modern languages that descended from and are the closest to Chagatai. Uzbeks regard Chagatai as the origin of their own language and consider the Chagatai literature as part of their heritage. In 1921 in Uzbekistan, then a part of the Soviet Union, Chagatai was initially planned to be instated as the national and governmental language of the Uzbek S.S.R., however when it became evident that the language was too archaic for that purpose, it was replaced by a new literary language based on series of Uzbek dialects.

The Berendei, a 12th-century nomadic Turkic people possibly related to the Cumans, seem also to have spoken Chagatai.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Ethnologue records the use of the word "Chagatai" in Afghanistan to describe the "Tekke" dialect of Turkmen.[17] Up to and including the eighteenth century, Chagatai was the main literary language in Turkmenistan as well as most of Central Asia.[18] While it had some influence on Turkmen, the two languages belong to different branches of the Turkic language family.

الأدب

القرنان 15 و 16

The most famous of the Chagatai poets is Ali-Shir Nava'i, who – among his other works – wrote Muhakamat al-Lughatayn, a detailed comparison of the Chagatai and Persian languages, in which he argued for the superiority of the former for literary purposes. His fame is attested by the fact that Chagatai is sometimes called "Nava'i's language". Among prose works, Timur's biography is written in Chagatai, as is the famous Baburnama (or Tuska Babure) of Babur, the Timurid founder of the Mughal Empire. A Divan attributed to Kamran Mirza is written in Persian and Chagatai, and one of Bairam Khan's Divans was written in the Chagatai language.

The following is a prime example of the 16th-century literary Chagatai Turkic, employed by Babur in one of his ruba'is.[19]

|

Islam ichin avara-i yazi bo'ldim, |

I am become a desert wanderer for Islam,

|

Uzbek ruler Muhammad Shaybani Khan wrote a prose essay called "Risale-yi maarif-i Shayibani" in the Central Asian Turkic - Chagatai language in 1507 shortly after his capture of Khorasan and is dedicated to his son, Muhammad Timur (the manuscript is kept in Istanbul) [20] The manuscript of his philosophical and religious work: "Bahr ul-Khudo", written in the Central Asian Turkic literary language in 1508 is located in London [21]

القرنان 17 و 18

Important writings in Chagatai from the period between the 17th and 18th centuries include those of Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur: Shajara-i Tarākima (Genealogy of the Turkmens) and Shajara-i Turk (Genealogy of the Turks). In the second half of the 18th century, Turkmen poet Magtymguly Pyragy also introduced the use of the classical Chagatai into Turkmen literature as a literary language, incorporating many Turkmen linguistic features.[22]

19th and 20th centuries

Prominent 19th century Khivan writers include Shermuhammad Munis and his nephew Muhammad Riza Agahi.[23] Muhammad Rahim Khan II of Khiva also wrote ghazals. Musa Sayrami's Tārīkh-i amniyya, completed 1903, and its revised version Tārīkh-i ḥamīdi, completed 1908, represent the best sources on the Dungan Revolt (1862–1877) in Xinjiang.[24][25]

القواميس والنحو

The following are books written on the Chagatai language by natives and westerners:[26]

- Vocabularium Linguae Giagataicae Sive Igureae (Lexico Ćiagataico)[27]

- Muḥammad Mahdī Khān, Sanglakh.

- Abel Pavet de Courteille, Dictionnaire turk-oriental (1870).

- Ármin Vámbéry 1832–1913, Ćagataische Sprachstudien, enthaltend grammatikalischen Umriss, Chrestomathie, und Wörterbuch der ćagataischen Sprache; (1867).

- Sheykh Süleymān Efendi, Čagataj-Osmanisches Wörterbuch: Verkürzte und mit deutscher Übersetzung versehene Ausgabe (1902).

- Sheykh Süleymān Efendi, Lughat-ï chaghatay ve turkī-yi 'othmānī (Dictionary of Chagatai and Ottoman Turkish).

- Mirza Muhammad Mehdi Khan Astarabadi, Mabaniul Lughat: Yani Sarf o Nahv e Lughat e Chughatai.[28]

- Abel Pavet de Courteille, Mirâdj-nâmeh : récit de l'ascension de Mahomet au ciel, composé a.h. 840 (1436/1437), texte turk-oriental, publié pour la première fois d'après le manuscript ouïgour de la Bibliothèque nationale et traduit en français, avec une préf. analytique et historique, des notes, et des extraits du Makhzeni Mir Haïder.[29]

الكتابة

Chagatai has been a literary language and is written with a variation of the Perso-Arabic alphabet. This variation is known as Kona Yëziq, (ترجمتها Old script). It saw usage for Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Uyghur, and Uzbek.

| Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial | Uzbek Letter name | Uzbek Latin | Kazakh | Kyrgyz | Uyghur |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ء | — | Hamza | ' | ∅/й | ∅/й | ئ | ||

| ا | ا | ا | alif | o, a | ә/а | а | ئا | |

| ب | ب | ب | ب | be | b | б | б | ب |

| پ | پ | پ | پ | pe | p | п | п | پ |

| ت | ت | ت | ت | te | t | т | т | ت |

| ث | ث | ث | ث | se | s | с | с | س |

| ج | ج | ج | ج | jim | j | ж | ж | ج |

| چ | چ | چ | چ | chim | ch | ш | ч | چ |

| ح | ح | ح | ح | hoy-i hutti | h | х, ∅ | х, ∅ | ھ |

| خ | خ | خ | خ | xe | x | қ | қ | х |

| د | د | د | dol | d | д | д | د | |

| ذ | ذ | ذ | zol | z | з | з | ز | |

| ر | ر | ر | re | r | р | р | ر | |

| ز | ز | ز | ze | z | з | з | ز | |

| ژ | ژ | ژ | je (zhe) | j | ж | ж | ژ | |

| س | س | س | س | sin | s | с | с | س |

| ش | ش | ش | ش | shin | sh | ш | ш | ش |

| ص | ص | ص | ص | sod | s | с | с | س |

| ض | ض | ض | ض | dod | z | з | з | ز |

| ط | ط | ط | ط | to (itqi) | t | т | т | ت |

| ظ | ظ | ظ | ظ | zo (izgʻi) | z | з | з | ز |

| ع | ع | ع | ع | ayn | ' | ∅ (ғ) | ∅ | ئ |

| غ | غ | غ | غ | gʻayn | gʻ | ғ | ғ | غ |

| ف | ف | ف | ف | fe | f | п (ф) | п/б (ф) | ف |

| ق | ق | ق | ق | qof | q | қ | қ | ق |

| ک | ک | ك | ك | kof | k | к | к | ك |

| گ | گ | گ | گ | gof | g | г | г | گ |

| نگ/ݣ | ـنگ/ـݣ | ـنگـ/ـݣـ | نگـ/ݣـ | nungof | ng | ң | ң | ڭ |

| ل | ل | ل | ل | lam | l | л | л | ل |

| م | م | م | م | mim | m | м | м | م |

| ن | ن | ن | ن | nun | n | н | н | ن |

| و | و | و | vav | v

oʻ, u |

у

ү/ұ, ө/о |

vбv

ү/у, ө/о |

ۋ

ئۈ/ئۇ، ئۆ/ئو | |

| ه | ه | ه | ه | hoy-i havvaz | h

a |

∅/й (h)

е/а |

∅/й

э/а |

ھ

ئە/ئا |

| ى | ى | ي | ي | yo | y

e, i |

й, и

і/ы, е |

й

и/ы, э |

ي

ئى، ئې |

Notes

The letters ف، ع، ظ، ط، ض، ص، ژ، ذ، خ، ح، ث، ء are only used in loanwords and don't represent any additional phonemes.

For Kazakh and Kyrgyz, letters in parentehsis () indicate a modern borrowed pronunciation from Tatar and Russian that is not consistent with historic Kazakh and Kyrgyz treatments of these letters.

Influence

Many orthographies, particularly that of Turkic languages, are based on Kona Yëziq. Examples include the alphabets of South Azerbaijani, Qashqai, Chaharmahali, Khorasani, Uyghur, Äynu, and Khalaj.

Virtually all other Turkic languages have a history of being written with an alphabet descended from Kona Yëziq, however, due to various writing reforms conducted by Turkey and the Soviet Union, many of these languages now are written in either the Latin script or the Cyrillic script.

The Qing dynasty commissioned dictionaries on the major languages of China which included Chagatai Turki, such as the Pentaglot Dictionary.

Punctuation

Below are some punctuation marks associated with Chagatai.[30]

| Symbol/

Graphemes |

Name | English name | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| ⁘ | Four-dot mark | The four-dot mark indicates a verse break. It is used at the beginning and end of a verse, especially to separate verse from prose. It may occur at the beginning or end of lines, or in the middle of a page. | |

| ❊ | Eight teardrop-spoked propeller asterisk | The eight teardrop-spoked propeller asterisk indicates a decoration for title. This mark occurs end of the title. This mark also occurs end of a poem. This mark occurs end of a prayer in Jarring texts. However this mark did not occur consistently. | |

| . | Period (full stop) | The period is a punctuation mark placed at the end of a sentence. However, this mark did not occur consistently in Chaghatay manuscripts until the later period (e.g. manuscripts on Russian paper). | |

| " " | Quotation mark | Dialogue was wrapped in quotation marks, rarely used for certain words with emphasis | |

| ___ | Underscore | Dash: mostly with red ink, occurs on the top of names, prayers, and highlighted questions, asnwers, and important outline numbers. | |

| Whitespace | Can indicate a stanza break in verse, and a new paragraph in brows. | ||

| - | Dash | Rare punctuation: used for number ranges (e.g. 2-5) | |

| -- | Double dash | Rare punctuation: sets off following information like a colon, it is used to list a table of contents | |

| ( ) | Parentheses | Marks a tangential or contextual remark, word or phrase. | |

| : | colon | Colons appear extremely rarely preceding a direct quote. Colons can also mark beginning of dialogue | |

| … | Ellipsis: | Ellipsis: a series of dots (typically 3) that indicate missing text. |

ملاحظات

المراجع

- ^ "CHAGHATAY LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE". Iranica.

Ebn Mohannā (Jamāl-al-Dīn, fl. early 8th/14th century, probably in Khorasan), for instance, characterized it as the purest of all Turkish languages (Doerfer, 1976, p. 243), and the khans of the Golden Horde (Radloff, 1870; Kurat; Bodrogligeti, 1962) and of the Crimea (Kurat), as well as the Kazan Tatars (Akhmetgaleeva; Yusupov), wrote in Chaghatay much of the time.

- ^ Ayşe Gül Sertkaya (2002). "Şeyhzade Abdurrezak Bahşı". In György Hazai (ed.). Archivum Ottomanicum. Vol. 20. pp. 114–115.

As a result, we can claim that Şeyhzade Abdürrezak Bahşı was a scribe lived in the palaces of Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror and his son Bayezid-i Veli in the 15th century, wrote letters (bitig) and firmans (yarlığ) sent to Eastern Turks by Mehmed II and Bayezid II in both Uighur and Arabic scripts and in East Turkestan (Chagatai) language.

- ^ أ ب János Eckmann (1966). "Chagatay Manual". In Thomas A. Sebeok (ed.). Uralic and Altaic Series. Vol. 60. Indiana University Publications. p. 4.

- ^ أ ب ت Paul Bergne (29 June 2007). Birth of Tajikistan: National Identity and the Origins of the Republic. I.B.Tauris. pp. 24, 137. ISBN 978-0-85771-091-8.

- ^ "Chagatai literature". Encyclopedia Britannica (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-09-19.

- ^ أ ب ت L.A. Grenoble (11 April 2006). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-306-48083-6.

- ^ Vaidyanath, R (1967). The Formation of the Soviet Central Asian Republics, A Study in Soviet Nationalities Policy, 1917-1936. People's Publishing House. p. 24.

- ^ Robert McHenry, ed. (1993). "Navā'ī, (Mir) 'Alī Shīr". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (15th ed.). Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. p. 563.

- ^ Vladimir Babak; Demian Vaisman; Aryeh Wasserman (23 November 2004). Political Organization in Central Asia and Azerbaijan: Sources and Documents. Routledge. pp. 343–. ISBN 978-1-135-77681-7.

- ^ Schiffman, Harold (2011). Language Policy and Language Conflict in Afghanistan and Its Neighbors: The Changing Politics of Language Choice. Brill Academic. pp. 178–179. ISBN 978-9004201453.

- ^ Scott Newton (20 November 2014). Law and the Making of the Soviet World: The Red Demiurge. Routledge. pp. 232–. ISBN 978-1-317-92978-9.

- ^ Andrew Dalby (1998). Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. Columbia University Press. pp. 665–. ISBN 978-0-231-11568-1.

Chagatai Old Uzbek official.

- ^ Allworth, Edward A. (1990). The Modern Uzbeks: From the Fourteenth Century to the Present: A Cultural History. Hoover Institution Press. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-0817987329.

- ^ Aramco World Magazine. Arabian American Oil Company. 1985. p. 27.

- ^ Pengyuan Liu; Qi Su (12 December 2013). Chinese Lexical Semantics: 14th Workshop, CLSW 2013, Zhengzhou, China, May 10-12, 2013. Revised Selected Papers. Springer. pp. 448–. ISBN 978-3-642-45185-0.

- ^ János Eckmann (1966). "Chagatay Manual". In Thomas A. Sebeok (ed.). Uralic and Altaic Series. Vol. 60. Indiana University Publications. p. 7.

- ^ "Turkmen language". Ethnologue.

- ^ Clark, Larry, Michael Thurman, and David Tyson. "Turkmenistan." Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan: Country Studies. p. 318. Comp. Glenn E. Curtis. Washington, D.C.: Division, 1997

- ^ Balabanlilar, Lisa (2015). Imperial Identity in the Mughal Empire. Memory and Dynastic Politics in Early Modern South and Central Asia. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 42–43. ISBN 0-857-72081-3.

- ^ Bodrogligeti A.J.E. Muḥammad Shaybānī Khan’s Apology to the Muslim Clergy // Archivum Ottomanicum. 1994a. Vol. 13. (1993/1994), р.98

- ^ A.J.E.Bodrogligeti, «Muhammad Shaybanî’s Bahru’l-huda : An Early Sixteenth Century Didactic Qasida in Chagatay», Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher, vol.54 (1982), p. 1 and n.4

- ^ Clark, Larry, Michael Thurman, and David Tyson. "Turkmenistan." Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan: Country Studies. p. 318. Comp. Glenn E. Curtis. Washington, D.C.: Division, 1997

- ^ [1]; Qahhar, Tahir, and William Dirks. “Uzbek Literature.” World Literature Today, vol. 70, no. 3, 1996, pp. 611–618. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40042097.

- ^ МОЛЛА МУСА САЙРАМИ: ТА'РИХ-И АМНИЙА (Mulla Musa Sayrami's Tarikh-i amniyya: Preface)], in: "Материалы по истории казахских ханств XV–XVIII веков (Извлечения из персидских и тюркских сочинений)" (Materials for the history of the Kazakh Khanates of the 15–18th cc. (Extracts from Persian and Turkic literary works)), Alma Ata, Nauka Publishers, 1969. (in روسية)

- ^ Kim, Ho-dong (2004). Holy war in China: the Muslim rebellion and state in Chinese Central Asia, 1864–1877. Stanford University Press. p. xvi. ISBN 0-8047-4884-5.

- ^ Bosworth 2001, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Onur 2020, pp. 136-157.

- ^ "Mabaniul Lughat: Yani Sarf o Nahv e Lughat e Chughatai - Mirza Muhammad Mehdi Khan Astarabadi (Farsi)" – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Haïder, Mir; Pavet de Courteille, Abel (1 January 1975). "Mirâdj-nâmeh : récit de l'ascension de Mahomet au ciel, composé a.h. 840 (1436/1437), texte turk-oriental, publié pour la première fois d'après le manuscript ouïgour de la Bibliothèque nationale et traduit en français, avec une préf. analytique et historique, des notes, et des extraits du Makhzeni Mir Haïder". Amsterdam : Philo Press – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Chaghatay manuscripts transcription handbook". uyghur.ittc.ku.edu. Retrieved 2021-11-13.

ببليوگرافيا

- Eckmann, János, Chagatay Manual. (Indiana University publications: Uralic and Altaic series ; 60). Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University, 1966. Reprinted edition, Richmond: Curzon Press, 1997, ISBN 0-7007-0860-X, or ISBN 978-0-7007-0860-4.

- Bodrogligeti, András J. E., A Grammar of Chagatay. (Languages of the World: Materials ; 155). München: LINCOM Europa, 2001. (Repr. 2007), ISBN 3-89586-563-X.

- Pavet de Courteille, Abel, Dictionnaire Turk-Oriental: Destinée principalement à faciliter la lecture des ouvrages de Bâber, d'Aboul-Gâzi, de Mir Ali-Chir Nevâï, et d'autres ouvrages en langues touraniennes (Eastern Turkish Dictionary: Intended Primarily to Facilitate the Reading of the Works of Babur, Abu'l Ghazi, Mir ʿAli Shir Navaʾi, and Other Works in Turanian Languages). Paris, 1870. Reprinted edition, Amsterdam: Philo Press, 1972, ISBN 90-6022-113-3. Also available online (Google Books)

- Erkinov, Aftandil. “Persian-Chaghatay Bilingualism in the Intellectual Circles of Central Asia during the 15th-18th Centuries (the case of poetical anthologies, bayāz)”. International Journal of Central Asian Studies. C.H.Woo (ed.). vol.12, 2008, pp. 57–82 [2].

- Cakan, Varis (2011) "Chagatai Turkish and Its Effects on Central Asian Culture", 大阪大学世界言語研究センター論集. 6 P.143-P.158, Osaka University Knowledge Archive.

وصلات خارجية

- Russian imperial policies in Central Asia

- Chagatai language at Encyclopædia Iranica

- An introduction to Chaghatay by Eric Schluessel, Maize Books; University of Michigan Publishing 2018 (A self study, open access textbook with graded lessons)

- Articles containing Chagatay-language text

- Articles with روسية-language sources (ru)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Languages with ISO 639-2 code

- Language articles with unreferenced extinction date

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- لغات إلصاقية

- Vowel-harmony languages

- Karluk languages

- جماعات بدوية في أوراسيا

- Timurid dynasty

- Chagatai Khanate

- لغات منقرضة في آسيا

- Languages attested from the 15th century

- Languages extinct in the 20th century

- Turkic languages