الإعادة للوطن من بلايبورگ

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| أعقاب الحرب العالمية الثانية في يوغسلاڤيا |

|---|

| الأحداث الرئيسية |

| المذابح |

| المعسكرات |

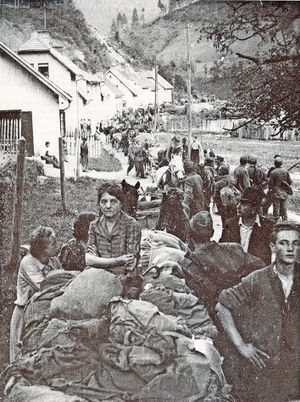

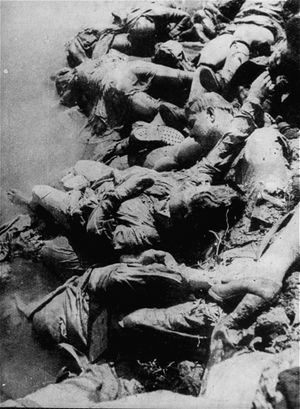

الإعادة للوطن من بلايبورگ (Bleiburg repatriations، انظر المسميات) حدثت في مايو 1945، في نهاية الحرب العالمية الثانية في أوروپا. عشرات الآلاف من الجنود والمدنيين المقترنين بقوى المحور فروا من يوغسلاڤيا إلى النمسا بمجرد سيطرة الاتحاد السوڤيتي (الجيش الأحمر) و الپارتيزان اليوغسلاڤ. الجيش البريطاني وضعهم في قطارات، قيل أنهم ظنوها متجهة غرباً في حين أنها اتجهت فعلاً إلى الشرق باتجاه يوغسلاڤيا ليقعوا في قبضة المارشال يوسيپ بروز تيتو، مما أجبرهم على الاستسلام لقوات الپارتيزان. أُجبِر الجنود وغيرهم على السير في مسيرات قسرية، مع أقوال استولى عليها الپارتيزان في يوغسلاڤيا. عشرات الآلاف من أولئك الرجال أُعدِموا؛ وآخرون أُخِذوا إلى معسكرات للأشغال الشاقة، حيث مات المزيد من الظروف القاسية. الأحداث سُمِّيت على اسم البلدة الحدودية الكارنثية بلايبورگ، حيث جرت أولى جهود الإعادة للوطن.

وفي 3 مايو 1945، قررت حكومة دولة كرواتيا المستقلة (NDH)، الدولة الفاشية الدُمية التي تأسست في أجزاء من يوغسلاڤيا المحتلة من قِبل الألمان أن تهرب إلى النمسا. وأمروا فلول القوات المسلحة الكرواتية (HOS) أن تتحرك إلى هناك بأقصى سرعة ممكنة لكي تستسلم للجيش البريطاني. أصدرت القيادة السلوڤينية المتحالفة مع المحور أمر تراجع للحرس المحلي السلوڤيني في نفس اليوم. تلك القوات، برفقة مدنيين، انضموا إلى German مجموعة الجيوش E الألمانية ووحدات المحور الأخرى في الانسحاب؛ وشملت الأخيرة الفيلق 15 SS فرسان القوزاق وفلول الچتنك المونتنگرية المنضوية في الجيش الوطني المونتنگري تحت قيادة القوات المسلحة الكرواتية (HOS). وكانوا قد رفضوا الاستسلام للجيش الأحمر أو للپارتيزان اليوغسلاڤ.

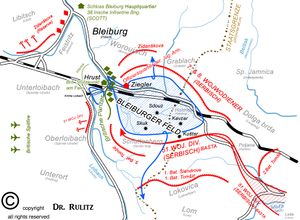

في الأسبوع التالي لوثيقة استسلام ألمانيا، التي أشرت بنهاية الحرب العالمية الثانية في أوروپا، واصلت قوات المحور في يوغسلاڤيا مقاتلة الپارتيزان لتفادي المحاصرة ولإبقاء طرق الهرب مفتوحة. The Slovene-led columns fought their way to the Austrian border near Klagenfurt on 14 May. Their surrender was accepted by the British and they were interned in the nearby Viktring camp. When one of the columns of fleeing HOS troops, who were intermingled with civilians, approached the town of Bleiburg on 15 May, the British refused to accept their surrender. They directed them to surrender to the Partisans, which the HOS leadership did after short negotiations. Other Axis prisoners in British captivity were repatriated to Yugoslavia in the following weeks. The repatriations were canceled by the British on 31 May, following reports of massacres in Yugoslavia.

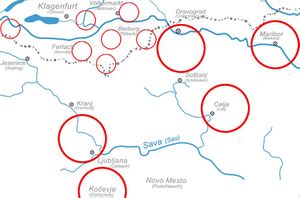

The Yugoslav authorities moved the prisoners on forced marches throughout the country to internment and labor camps. Mass executions were carried out, the largest of which were in Tezno, Kočevski Rog and Huda Jama. These massacres and other abuses after the repatriations was a taboo topic in Yugoslavia and information about the events was suppressed. Public and official commemoration of the victims did not begin until several decades later. Historians have been unable to accurately ascertain the number of casualties during and after the repatriations; exact numbers have been the subject of much debate.

المسميات

Commonly used terms such as Bleiburg massacre, Bleiburg tragedy, Bleiburg crime, Bleiburg case, and also simply Bleiburg, are used in Croatia to refer to the events in question.[1][2][3] The term Way of the Cross (كرواتية: Križni put) is a common subjective term, used mostly by Croatians, regarding the events after the repatriations.[1] The latter have been described as "death marches".[4][5]

Among Slovenes, the term Viktring tragedy (Slovene: Vetrinjska tragedija) is commonly used. Viktring was a British camp where the largest number of Slovene prisoners were interned before the repatriations took place.[6]

خلفية

When World War II broke out in 1939, the government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia declared its neutrality.[7] By the beginning of 1941, most of its neighbours joined the Tripartite Pact.[8] Yugoslavia came under strong pressure to join the Axis and the Yugoslav government signed the Pact on 25 March 1941, the year that Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. But demonstrations broke out in Belgrade against the decision, and on 27 March, the opposition overthrew the government in a coup d'état. The new Yugoslav government refused to ratify the signing of the Tripartite Pact, though it did not rule it out. Adolf Hitler reacted by launching the invasion of Yugoslavia on 6 April 1941, allied with forces of Italy and Hungary.[9]

On 10 April, German troops entered Zagreb and on the same day, the Independent State of Croatia (كرواتية: Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH) was declared, an Axis puppet state led by the Ustaše. Ante Pavelić was named the Poglavnik ("leader") of NDH.[10] Yugoslavia capitulated to the Axis powers on 17 April.[11]

The rump Serbian territory was placed under German military administration, with the help of a civil puppet government led by Milan Nedić.[12] Slovene lands were divided among Germany, Italy and Hungary.[13]

Following the occupation and division of Yugoslavia, the fascist governments introduced anti-semitic laws in accordance with the Nazi Final Solution plan.[14] The Ustaše also enacted racial laws and systematically persecuted Serbs, who were Orthodox Christian, as well as Jewish and Roma populations throughout the country. It established a concentration camp system, the largest of which was Jasenovac,[15] where 77,000–100,000 people were murdered.[16] Around 29–31,000 Jews, or 79% of their pre-war population in the NDH, was killed during the Holocaust, mostly by the Ustaše.[17] Almost the entire Roma population of around 25,000 was annihilated.[18]

The number of Serbs killed by the Ustaše is difficult to determine.[19] The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum estimates that the Ustaše killed between 320,000–340,000 Serbs in 1941 and 1942 alone.[20] Croatian demographer Vladimir Žerjavić calculated the population losses of Yugoslavia, and estimated the total number of Serb civilian and combatant deaths in the NDH at 322,000. Of the civilian casualties, he estimated that the Ustaše killed 78,000 Serb civilians, in direct terror and in concentration camps, and the rest died at the hands of the German and Italian forces, and of other causes.[4] A series of massacres led to armed revolts of Serbs against the DH. Wehrmacht General Edmund Glaise-Horstenau blamed the Ustaše crimes for the uprisings and criticised the government of NDH.[21]

In the wake of the invasion, remnants of the Royal Yugoslav Army organized the Serbian monarchist Chetniks as the first resistance movement. The Chetniks were led by Draža Mihailović and were recognized by the Yugoslav government-in-exile.[22] The Communist Party of Yugoslavia refrained from open conflict with the Axis forces while the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union was in effect. Following the start of Operation Barbarossa in 1941, the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, Communist-led Yugoslav Partisans issued a call for an uprising.[23]

Josip Broz Tito was the supreme commander of the Partisan forces. The Chetniks and the Partisans, the two main guerrilla resistance units, initially cooperated against the Axis, but their cooperation soon fell apart, and they turned against each other. The Chetniks started to collaborate with the Axis, and Allied support shifted to the Partisan side.[24][25]

نهاية الحرب

انسحاب المحور

طريق الهروب إلى بلايبورگ

الاستسلام في بلايبورگ

إعادات أخرى للوطن من كارنثيا

موقف الحلفاء

At the Yalta Conference on 11 February 1945, an agreement was reached on the repatriation of citizens from the signatory states, the US, the UK, and the USSR, to their country of origin. As Yugoslavia was not a signatory, the repatriation of Yugoslav citizens was not mentioned in the agreement. At the time of the Axis retreat from occupied Yugoslavia, the British 5th Corps of the 8th Army was stationed in southern Austria, which was within the area of authority of Field Marshal Harold Alexander.[26] The Yugoslav Army reached southern Carinthia in early May and declared it a part of Yugoslavia. This caused strained relations with the British, who supported an independent Austria in prewar borders.[26][27] Due to Yugoslav refusal to withdraw from Austrian Carinthia, as well as from the Italian city of Trieste, the possibility of an armed conflict between the British forces and the Partisans emerged.[28]

The Western Allies did not expect the movement of a large number of people in the 5th Corps area.[29] The retreat of larger groups of "anti-Tito forces" was reported by Ralph Stevenson, the British ambasador in Belgrade, on 27 April.[30] There was no consensus among British authorities on how to deal with them. Stevenson recommended their internment in camps rather than repatriation.[28] British Prime Minister Winston Churchill agreed with Stevenson's suggestion as "the only possible solution".[31] The 8th Army issued an order on 3 May that Axis forces from Yugoslavia "will be regarded as surrendered personnel and will be treated accordingly. The ultimate disposal of these personnel will be decided on Government levels".[32] Until 14 May, the British accepted the surrender of thousands of retreating troops and civilians.[33]

A report to the 5th Corps from 13 May noted the movement of hundreds of thousands of people towards Austria. On the following day, the 5th Corps estimated that once the columns arrived, the food situation would become critical, and cited an insufficient number of guards to manage the people.[34] Harold Macmillan, the British Minister Resident in the Mediterranean, recommended the immediate transfer of Cossacks to the Soviet Union. Regarding the column that was approaching Bleiburg, the brigade stationed in the town was instructed to "keep it south of the Drava".[35] Brian Robertson, Alexander's Chief Administrative Officer, issued an order to the 8th British Army on 14 May to hand over all surrendered Axis personnel of Yugoslav nationality to the Yugoslav Army.[36] The order excluded Chetniks, who were to be transferred to Italy. The repatriations were opposed by Alexander Kirk, American political advisor to the Supreme Headquarters (SHAEF), who asked the US State Department for advice. Joseph Grew, the US Under Secretary of State, agreed with Kirk and instructed him to inform the Allied Force Headquarters (AFHQ) of "violation of the agreed Anglo-American policy".[37]

The AFHQ contacted the Yugoslav authorities on 15 May regarding the repatriation of "Yugoslavs".[28] In line with the orders received by 15 May, the 5th Corps rejected the surrender of the column at Bleiburg. At the same time, the 5th Corps entered negotiations with Yugoslav representatives regarding the repatriation of other POWs and the withdrawal of the Yugoslav Army from Carinthia. An agreement was reached for the Yugoslav withdrawal on 21 May.[38] The repatriations began earlier, on 18 May.[39]

A November 1945 report from the British Foreign Office noted that it had not yet been decided on a high level whether the prisoners should be transferred to Yugoslavia.[40] Local British commanders were given imprecise and contradictory orders. On 17 May, Brigadier Toby Low, Chief of Staff of the 5th Corps, ordered that "all Yugoslav nationals at present in Corps area will be handed over to Tito forces as soon as possible. These forces will be disarmed immediately but will NOT be told of their destination".[41] Several hours later, an order arrived from Alexander to evacuate all Yugoslav prisoners to northern Italy.[41] On the same day, Alexander sent a telegram to the Combined Chiefs of Staff, in which he wrote that to return the prisoners to their country of origin "might be fatal to their health".[42]

Instructions and provisions made by the Allies in the following days frequently conflicted.[43] Two conflicting instructions from the AFHQ arrived on 23 May: the first was to return the Yugoslav citizens from the 8th Army area to Yugoslavia unless it involved the use of force. The second instruction was that Yugoslav citizens should not be returned to Yugoslavia against their will, and that they should be "moved to suitable concentration area and screened".[44] The confusion in the line of command led to a series of meetings between the AFHQ representatives and the 8th Army. The conclusion of the meetings on 27 May was an implicit support to the policy of not telling the prisoners their destination, the non-use of force, and that "it was unwise to make any further interpretation".[45][46] The repatriations continued until 31 May, when they were canceled following the appeal of the head of the Viktring camp and the local British Red Cross.[47]

مسيرة العودة

التغطية الإعلامية والأعقاب

The events in the aftermath of the war were censored in Yugoslavia. Mass graves were concealed or destroyed, in accordance with an order by the Federal Ministry of Interior Affairs from 18 May 1945.[48] Relatives of the victims faced persecution and were treated as second class groups.[49] Until the 1950s, there were strict border controls in Yugoslavia, but tens of thousands of people emigrated illegally.[50]

التحقيقات في المقابر الجماعية

الذكرى

التخليد

مواقع تذكارية

نصب تذكاري في زغرب في مقبرة ميروگوي، كرواتيا

لوح تذكاري في Bistrica ob Sotli، سلوڤينيا

منتزه تهارييه التذكاري، سلوڤينيا

See also

- Allied war crimes during World War II

- List of massacres in Slovenia

- Mass killings under communist regimes

- Operation Keelhaul

- Persecution of Danube Swabians

Notes

- ^ أ ب Dizdar, 2005

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةYatBT-1999 - ^ Grahek Ravančić, 2008

- ^ أ ب Vladimir Žerjavić, Yugoslavia, Manipulations with the Number of Second World War Victims, hic.hr; accessed 18 September 2015.

- ^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 765.

- ^ Rulitz 2015, p. 1.

- ^ Pavlowitch 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 130.

- ^ Tomasevich 2001, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 142.

- ^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 53.

- ^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 63.

- ^ Hančič & Podberšič 2008, p. 44.

- ^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 583.

- ^ Rulitz 2015, p. 12.

- ^ "Jasenovac". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Cvetković 2011, p. 182.

- ^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 610.

- ^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 718.

- ^ "Axis Invasion of Yugoslavia". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 157.

- ^ Rulitz 2015, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Rulitz 2015, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 226.

- ^ Rulitz 2015, p. 17.

- ^ أ ب Rulitz 2015, pp. 54-55.

- ^ Corsellis & Ferrar 2015, pp. 41-42.

- ^ أ ب ت Corsellis & Ferrar 2015, p. 48.

- ^ Vuletić 2007, p. 142.

- ^ Grahek Ravančić 2009, p. 120.

- ^ Booker 1997, p. 147.

- ^ Grahek Ravančić 2009, pp. 124-125.

- ^ Ferenc 2008, p. 155.

- ^ Grahek Ravančić 2009, pp. 134-135.

- ^ Grahek Ravančić 2009, p. 138.

- ^ Rulitz 2015, p. 56.

- ^ Grahek Ravančić 2009, pp. 133, 135.

- ^ Rulitz 2015, pp. 56-57.

- ^ Corsellis & Ferrar 2015, p. 50.

- ^ Booker 1997, p. 298.

- ^ أ ب Corsellis & Ferrar 2015, pp. 49-50.

- ^ Corsellis & Ferrar 2015, p. 65.

- ^ Grahek Ravančić 2009, p. 171.

- ^ Booker 1997, p. 237.

- ^ Grahek Ravančić 2009, p. 174.

- ^ Booker 1997, p. 228.

- ^ Corsellis & Ferrar 2015, pp. 61-62.

- ^ Ferenc 2008, p. 157.

- ^ Dežman 2008, p. 201.

- ^ Hančič & Podberšič 2008, p. 55.

Bibliography

- Booker, Christopher (1997). A Looking-Glass Tragedy: The Controversy Over The Repatriations From Austria In 1945. London, UK: Gerald Duckworth & Co Ltd. ISBN 9780715627389.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Corsellis, John; Ferrar, Marcus (2015). Slovenia 1945: memories of death and survival after World War II. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781848855342.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dizdar, Zdravko (December 2005). "Prilog istraživanju problema Bleiburga i križnih putova (u povodu 60. obljetnice)" [An addition to the research of the problem of Bleiburg and the Way of the Cross (dedicated to their 60th anniversary)]. The Review of Senj (in Croatian). Senj, Croatia: City Museum Senj - Senj Museum Society. 32 (1): 117–193. ISSN 0582-673X.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Ferenc, Mitja (2008). "Secret World War Two mass graves in Slovenia" (PDF). In Jambrek, Peter (ed.). Crimes Committed by Totalitarian Regimes. Ljubljana: Slovenian Presidency of the Council of the European Union. ISBN 978-961-238-977-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ferenc, Mitja (2012). "Tezno – najveće prikriveno grobište u Sloveniji. O istraživanju grobišta u protutenkovskom rovu u Teznom (Maribor)" [Tezno – The Biggest Hidden Mass Burial Site in Slovenia. On the Research of the Hidden Burial Site in the Antitank Ditch in Tezno (Maribor)]. Journal of Contemporary History (in Croatian). Ljubljana: Oddelek za zgodovino Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani. 44: 539–569.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Geiger, Vladimir (2012). "Human losses of Croats in World War II and the immediate post-war period caused by the Chetniks (Yugoslav Army in the Fatherland) and the Partisans (People's Liberation Army and the partisan detachment of Yugoslavia/Yugoslav Army) and the Yugoslav Communist authoritities. Numerical indicators". Review of Croatian History. Croatian institute of history. 8 (1): 77–121.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Glenny, Misha (1999). The Balkans: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers, 1804–1999. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-85338-0.

- Grahek Ravančić, Martina (2009). Bleiburg i križni put 1945: historiografija, publicistika i memoarska literatura [Bleiburg and the Death Marches 1945. Historiography, journalism and memoirs] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Hrvatski institut za povijest. ISBN 9789536324798.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Grahek Ravančić, Martina (January 2008). "Izručenja zarobljenika s bleiburškog polja i okolice u svibnju 1945" [The handing over of prisoners from Bleiburg field and its surroundings in May 1945]. Journal of Contemporary History (in Croatian). Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History. 39 (3): 531–550. ISSN 0590-9597. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Hančič, Damjan; Podberšič, Renato (2008). "Totalitarian regimes in Slovenia in the 20th century" (PDF). In Jambrek, Peter (ed.). Crimes Committed by Totalitarian Regimes. Ljubljana: Slovenian Presidency of the Council of the European Union. ISBN 978-961-238-977-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jancar-Webster, B. (1989). Women & revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945. Denver: Arden Press.

- Kranjc, Gregor Joseph (2013). To Walk with the Devil : Slovene Collaboration and Axis Occupation, 1941-1945. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1442613300.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Klemenčič, Matjaž; Žagar, Mitja (2004). The Former Yugoslavia's Diverse Peoples: A Reference Sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-294-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lowe, Keith (2012). Savage Continent - Europe in the Aftermath of World War II. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 9781250015044.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - MacDonald, David Bruce (2003). Balkan holocausts?: Serbian and Croatian victim-centered propaganda and the war in Yugoslavia. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6467-8.

- Mikola, Milko (2008). "Concentration and labour camps in Slovenia" (PDF). In Jambrek, Peter (ed.). Crimes Committed by Totalitarian Regimes. Ljubljana: Slovenian Presidency of the Council of the European Union. ISBN 978-961-238-977-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Miladinović, Veljko (1991). Prva proleterska. Knj. 4 [1st Proletarian Brigade. Book 4]. Beograd: Vojnoizdavački zavod JNA "Vojno delo". OCLC 441105996.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Musgrove, D., ed. (2009). BBC History Magazine, Falsified Yugoslav Handover to Tito. Bristol: BBC Worldwide Publications. ISBN 978-0-9562036-2-5.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2008). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-1-85065-895-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pavlaković, Vjeran (2010). "Deifying the Defeated. Commemorating Bleiburg since 1990". L'Europe en Formation. Centre international de formation européenne. 3 (357): 125–147. doi:10.3917/eufor.357.0125.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Portmann, Michael (2004). "Communist Retaliation and Persecution on Yugoslav Territory During and After World War II (1943-1950)". Tokovi Istorije. Institut za noviju istoriju Srbije (1–2): 45–74.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Prcela, John Ivan; Živić, Dražen (2001). Hrvatski holokaust [Croatian Holocaust] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Hrvatsko društvo političkih zatvorenika. ISBN 9789539776020.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Radelić, Zdenko (2016). "1945 in Croatia". Review of Croatian History. Hrvatski institut za povijest. XII (1): 9–66.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Democratic transition in Croatia: value transformation, education & media. Texas A&M University Press. 2007. ISBN 978-1-58544-587-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34656-8.

- Rees, Laurence (2007). Their Darkest Hour: People Tested to the Extreme in WWII. London: Ebury Press. ISBN 978-0-09-191757-9.

- Ridley, Jasper S. (1994). Tito. Constable. ISBN 0-09-471260-3.

- Rulitz, Florian Thomas (2015). The Tragedy of Bleiburg and Viktring, 1945. Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 9781609091774.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tanner, Marcus (2001). Croatia: A Nation Forged in War. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09125-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Axis Forces in Yugoslavia 1941–45. London: Osprey. 1995. ISBN 1-85532-473-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - Tolstoy, Nikolai (1986). The Minister and the Massacres. Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09-164010-1.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: The Chetniks. Vol. 1. San Francisco: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Vol. 2. San Francisco: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3615-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vucinich, Wayne S.; Tomasevich, Jozo (1969). Contemporary Yugoslavia: twenty years of Socialist experiment. University of California Press.

- Vuletić, Dominik (December 2007). "Kaznenopravni i povijesni aspekti bleiburškog zločina". Lawyer (in Croatian). Zagreb, Croatia: Pravnik. 41 (85): 125–150. ISSN 0352-342X.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Žerjavić, Vladimir (1995). "Demografski i ratni gubici Hrvatske u Drugom svjetskom ratu i poraću" [Demographic and War Losses of Croatia in the World War Two and in the Postwar Period]. Journal of Contemporary History (in Croatian). Zagreb, Croatia. 27 (3): 543–559.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

للاستزادة

- Cohen, P.J., Riesman, D., Serbia's Secret War: Propaganda and the Deceit of History, Texas A&M University Press, 1996; ISBN 0-89096-760-1

- Epstein, Julius (1973). Operation Keelhaul: the story of forced repatriation from 1944 to the present. Devin-Adair Co. ISBN 978-0-8159-6407-0.

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Articles containing كرواتية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing Slovene-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- CS1 errors: deprecated parameters

- Austria articles missing geocoordinate data

- All articles needing coordinates

- 1945 في يوغسلاڤيا

- نزاعات 1945

- التاريخ المعاصر لسلوڤينيا

- دولة كرواتيا المستقلة

- Massacres in Yugoslavia

- Yugoslav war crimes

- Mass murder in 1945

- World War II prisoners of war massacres

- Politicides

- تطهير سياسي وثقافي

- القمع السياسي في يوغسلاڤيا الشيوعية

- Post–World War II forced migrations

- أعقاب الحرب العالمية الثانية في يوغسلاڤيا