موطن الآشوريين

Assyria | |

|---|---|

Star of Shamash

| |

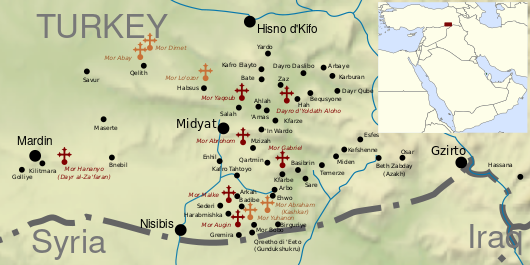

![The Assyrian Triangle had the greatest concentration of indigenous Assyrians in both their native land and the world prior to the 2014 invasion of Iraq by ISIS,[1] and was the proposed borders for an autonomous Assyrian state following World War I.[2]](/w/images/thumb/1/1c/Assyria_World_War_1_relief_English.png/350px-Assyria_World_War_1_relief_English.png) The Assyrian Triangle had the greatest concentration of indigenous Assyrians in both their native land and the world prior to the 2014 invasion of Iraq by ISIS,[1] and was the proposed borders for an autonomous Assyrian state following World War I.[2] | |

| أكبر مدينة | Qaraqosh, Iraq |

| اللغات الرسمية | |

| اللغات الوطنية المعترف بها | Neo-Aramaic |

| اللغات الإقليمية المعترف بها | Mesopotamian Arabic, Turkish, Kurdish and Persian. |

| الجماعات العرقية | Assyrian people (historical majority) |

| الدين | Syriac Christianity |

| صفة المواطن | Assyrian Syrian, Syriac (historically) |

| اليوم جزء من | |

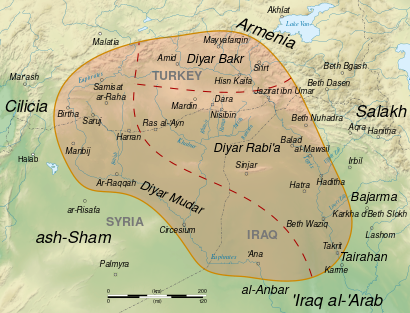

The Assyrian homeland, Assyria (سريانية الكلاسيكية: ܐܬܘܪ, romanized: Āṯōr or سريانية الكلاسيكية: ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, romanized: Bêṯ Nahrin), refers to the homeland of the Assyrian people within which Assyrian civilisation developed, located in their indigenous Upper Mesopotamia. The territory that forms the Assyrian homeland is, similarly to the rest of Mesopotamia, currently divided between present-day Iraq, Turkey, Iran and Syria.[3] In Iran, the Urmia Plain forms a thin margin of the ancestral Assyrian homeland in the north-west, and the only section of the Assyrian homeland beyond the Mesopotamian region. The majority of Assyrians in Iran currently reside in the capital city, Tehran.[4]

The Assyrians are indigenous Mesopotamians, descended from the Akkadians, Sumerians and Hurrians[5][6][7] who developed independent civilisation in the city of Assur on the eastern border of northern Mesopotamia. The territory that would encompass the Assyrian homeland was divided through the centre by the Tigris River, with their indigenous Mesopotamia on the west and western margins of the Urmia Plains, which they occupied in 2000 BCE prior to the arrival of the modern Iranians, to the east. In modern times, Assyrians largely only recognise Assyrian towns and cities immediately neighbouring the Tigris to the east as their indigenous territory, in addition to Mesopotamia,[8][9] with the homeland only expanding beyond the borders due to the major centres of Assyrian civilisation, such as the cities of Nineveh, Assur and Nimrud, being built on the banks of the Tigris itself.

Modern Assyrians are predominantly Christian, mostly adhering to the East and West Syriac liturgical rites of Christianity.[10] They speak Neo-Aramaic languages, most common being Suret and Turoyo.[11]

History

Ancient period

The city of Aššur and Nineveh (modern-day Mosul), which was the oldest and largest city of the ancient Assyrian empire,[12] together with a number of other Assyrian cities, seem to have been established by 2600 BC. However it is likely that they were initially Sumerian-dominated administrative centres. In the late 26th century BC, Eannatum of Lagash, then the dominant Sumerian ruler in Mesopotamia, mentions "smiting Subartu" (Subartu being the Sumerian name for Assyria). Similarly, in c. the early 25th century BC, Lugal-Anne-Mundu the king of the Sumerian state of Adab lists Subartu as paying tribute to him.[13]

Assyrians are eastern Aramaic-speaking, descending from pre-Islamic inhabitants of Upper Mesopotamia. The Old Aramaic language was adopted by the population of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from around the 8th century BC, and these eastern dialects remained in wide use throughout Upper Mesopotamia during the Persian and Roman periods, and survived through to the present day. The Syriac language evolved in Achaemenid Assyria during the 5th century BC.[14][15]

During the Assyrian period Duhok was named Nohadra (and also Bit Nuhadra' or Naarda), where, during the Parthian-Sassanid rule in Assyria (c.160 BC to 250 AD) as Beth Nuhadra, gained semi-independence as one of a patchwork of Neo-Assyrian kingdoms in Assyria, which also included Adiabene, Osroene, Assur and Beth Garmai.[16][17]

Early Christian period

Syriac Christianity took hold amongst the Assyrians between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD with the founding in Assyria of the Church of the East together with Syriac literature.[18]

The first division between Syriac Christians occurred in the 5th century, when Upper Mesopotamian based Assyrian Christians of the Sassanid Persian Empire were separated from those in The Levant over the Nestorian Schism. This split owed just as much to the politics of the day as it did to theological orthodoxy. Ctesiphon, which was at the time the Sassanid capital, eventually became the capital of the Church of the East. During the Christian era Nuhadra became an eparchy within the Assyrian Church of the East metropolitanate of Ḥadyab (Erbil).[19]

After the Council of Chalcedon in 451, many Syriac Christians within the Roman Empire rebelled against its decisions. The Patriarchate of Antioch was then divided between a Chalcedonian and non-Chalcedonian communion. The Chalcedonians were often labelled 'Melkites' (Emperor's Party), while their opponents were labelled as Monophysites (those who believe in the one rather than two natures of Christ) and Jacobites (after Jacob Baradaeus). The Maronite Church found itself caught between the two, but claims to have always remained faithful to the Catholic Church and in communion with the bishop of Rome, the Pope.[20]

Middle Ages

Both Syriac Christianity and the Eastern Aramaic language came under pressure following the Arab Islamic conquest of Mesopotamia in the 7th century, and Assyrian Christians throughout the Middle Ages were subjected to Arabizing superstrate influence. The Assyrians suffered a significant persecution with the religiously motivated large scale massacres conducted by the Muslim Turco-Mongol ruler Tamurlane in the 14th century AD. It was from this time that the ancient city of Assur was abandoned by Assyrians, and Assyrians were reduced to a minority within their ancient homeland.[21][22]

Upper Mesopotamia had an established structure of dioceses by AD 500 following the introduction of Christianity from the 1st to 3rd centuries AD.[23] After the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire by 605 BC Assyria remained an entity for over 1200 years under Babylonian, Achamaenid Persian, Seleucid Greek, Parthian, Roman and Sassanid Persian rule. It was only after the Arab-Islamic conquest of the second half of the 7th century AD that Assyria as a named region was dissolved.

The mountainous region of the Assyrian homeland, Barwari, which was part of the diocese of Beth Nuhadra (current day Dohuk), saw a mass migration of Nestorians after the fall of Baghdad in 1258 and Timurlane's invasion from central Iraq.[24] Its Christian inhabitants were little affected by the Ottoman conquests, however starting from the 19th century Kurdish Emirs sought to expand their territories at their expense. In the 1830s Muhammad Rawanduzi, the Emir of Soran, tried to forcibly add the region to his dominion pillaging many Assyrian villages. Bedr Khan Beg of Bohtan renewed attacks on the region in the 1840s, killing tens of thousands of Assyrians in Barwari and Hakkari before being ultimately defeated by the Ottomans.[25]

In 1552, a schism occurred within the Church of the East: the established "Eliya line" of patriarchs was opposed by a rival patriarch, Sulaqa, who initiated what is called the "Shimun line". He and his early successors entered into communion with the Catholic Church, but in the course of over a century their link with Rome grew weak and was openly renounced in 1672, when Shimun XIII Dinkha adopted a profession of faith that contradicted that of Rome, while he maintained his independence from the "Eliya line". Leadership of those who wished to be in communion with Rome passed to the Archbishop of Amid Joseph I, recognized first by the Turkish civil authorities (1677) and then by Rome itself (1681).[26][27][28][29]

A century and a half later, in 1830, headship of the Catholics was conferred on Yohannan Hormizd. Yohannan was a member of the "Eliya line" family, but he opposed the last of that line to be elected in the normal way as patriarch, Ishoʿyahb (1778–1804), most of whose followers he won over to communion with Rome, after he himself was irregularly elected in 1780, as Sulaqa was in 1552. The "Shimun line" that in 1553 entered communion with Rome and broke it off in 1672 is now that of the church that in 1976 officially adopted the name "Assyrian Church of the East",[30][31][32][33] while a member of the "Eliya line" family is one of the patriarchs of the Chaldean Catholic Church.

For many centuries, from at least the time of Jerome (c. 347 – 420),[34] the term "Chaldean" indicated the Aramaic language and was still the normal name in the nineteenth century.[35][36][37] Only in 1445 did it begin to be used to mean Aramaic speakers in communion with the Catholic Church, on the basis of a decree of the Council of Florence,[38] which accepted the profession of faith that Timothy, metropolitan of the Aramaic speakers in Cyprus, made in Aramaic, and which decreed that "nobody shall in future dare to call [...] Chaldeans, Nestorians".[39][40][41]

Previously, when there were as yet no Catholic Aramaic speakers of Mesopotamian origin, the term "Chaldean" was applied with explicit reference to their "Nestorian" religion. Thus Jacques de Vitry wrote of them in 1220/1 that "they denied that Mary was the Mother of God and claimed that Christ existed in two persons. They consecrated leavened bread and used the 'Chaldean' (Syriac) language".[42] Until the second half of the 19th century the term "Chaldean" continued in general use for East Syriac Christians, whether "Nestorian" or Catholic:[43][44][45][46] it was the West Syriacs who were reported as claiming descent from Asshur, the second son of Shem.[47]

Early modern period

Peutinger's map of the inhabited world known to the Roman geographers depicts Singara as located west of the Trogoditi. Persi. (لاتينية: Troglodytae Persiae, "Persian troglodytes") who inhabited the territory around Mount Sinjar. By the medieval Arabs, most of the plain was reckoned as part of the province of Diyār Rabīʿa, the "abode of the Rabīʿa" tribe. The plain was the site of the determination of the degree by al-Khwārizmī and other astronomers during the reign of the caliph al-Mamun.[48] Sinjar boasted a famous Assyrian cathedral in the 8th century.[49]

Syria and Upper Mesopotamia became part of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century, following the conquests of Suleiman the Magnificent.[50]

Modern period

During World War I the Assyrians suffered the Assyrian genocide which reduced their numbers by up to two thirds. Subsequent to this, they entered the war on the side of the British and Russians. After World War I, the Assyrian homeland was divided between the British Mandate of Mesopotamia, which would become the Kingdom of Iraq in 1932, and the French Mandate of Syria which would become the Syrian Arab Republic in 1944.[51][52][53][54]

Assyrians faced reprisals under the Hashemite monarchy for co-operating with the British during the years after World War I, and many fled to the West. The Patriarch Shimun XXI Eshai, though born into the line of Patriarchs at Qochanis, was educated in Britain. For a time he sought a homeland for the Assyrians in Iraq but was forced to take refuge in Cyprus in 1933, later moving to Chicago, Illinois, and finally settling near San Francisco, California.[55]

The Chaldean Christian community was less numerous[بحاجة لمصدر] and vociferous at the time of the British Mandate of Mesopotamia, and did not play a major role in the British rule of the country. However, with the exodus of Assyrian Church of the East members, the Chaldean Catholic Church became the largest non-Muslim religious denomination in Iraq, and some Assyrian Catholics later rose to power in the Ba'ath Party government, the most prominent being Deputy Prime Minister Tariq Aziz. The Assyrians of Dohuk boast one of the largest churches in the region named the Mar Marsi Cathedral, and is the center of an Eparchy. Tens of thousands of Yazidi and Assyrian Christian refugees live in the city as well due to the ISIS invasion of Iraq in 2014 and the subsequent Fall of Mosul[56]

In addition to the Assyrian population, an Aramaic speaking Jewish population existed in the region for thousands of years, living mainly in Barwari, Zakho and Alqosh. However, all of the Barwari Jews either left or were exiled to Israel shortly after its independence in 1947. The region was heavily affected by the Kurdish uprisings during the 1950s and 60s and was largely depopulated during the Al-Anfal campaign in the 1980s, although some of its population later returned and their homes were subsequently rebuilt.[57] Assur, which is in the Saladin Governorate, was put on UNESCO's List of World Heritage in danger in 2003, at which time the site was threatened by a looming large-scale dam project that would have submerged the ancient archaeological site.[58]

Attacks on Christians

Following the concerted attacks on Assyrian Christians in Iraq, especially highlighted by the Sunday, August 1, 2004, simultaneous bombing of six Churches (Baghdad and Mosul) and subsequent bombing of nearly thirty other churches throughout the country, Assyrian leadership, internally and externally, began to regard the Nineveh Plain as the location where security for Christians may be possible. Schools especially received much attention in this area and in Kurdish areas where Assyrian concentrated population lives. In addition, agriculture and medical clinics received financial help from the Assyrian diaspora.[59]

As attacks on Christians increased in Basra, Baghdad, Ramadi and smaller towns more families turned northward to the extended family holdings in the Nineveh Plain. This place of refuge remains underfunded and gravely lacking in infrastructure to aid the ever-increasing internally displaced people population. From 2012, it also began receiving influxes of Assyrians from Syria owing to the civil war there.[60][61]

In August 2014 nearly all of the non-Sunni inhabitants of the southern regions of the Plains, which include Tel Keppe, Bakhdida, Bartella and Karamlesh were driven out by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant during the 2014 Northern Iraq offensive.[62][63] Upon entering the town, ISIS looted the homes, and removed the crosses and other religious objects from the churches. The Christian cemetery in the town was also later destroyed.[64] Assyrian Bronze Age and Iron Age monuments and archaeological sites, as well as numerous Assyrian churches and monasteries have been systematically vandalized and destroyed by ISIL. These include the ruins of Nineveh, Kalhu (Nimrud, Assur, Dur-Sharrukin and Hatra).[65][66] ISIL destroyed a 3,000 year-old Ziggurat. ISIL destroyed Virgin Mary Church, in 2015 St. Markourkas Church was destroyed and the cemetery was bulldozed.[67]

Soon after the beginning of the Battle of Mosul Iraqi troops advanced on Tel Keppe, but the fighting continued into 2017.[68][69] Iraqi forces recaptured the town from ISIS on 19 January 2017.[59]

Geography

Climate

Owing to its latitude and altitude, the Assyrian homeland is cooler and much wetter than most of Iraq. Most areas in the region fall within the Mediterranean climate zone (Csa), with areas to the southwest being semi-arid (BSh).[70]

| Climate data for Tel Keppe | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 12 (54) |

14 (57) |

20 (68) |

26 (79) |

34 (93) |

38 (100) |

43 (109) |

40 (104) |

38 (100) |

30 (86) |

20 (68) |

14 (57) |

27 (81) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

4 (39) |

8 (46) |

11 (52) |

16 (61) |

21 (70) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

20 (68) |

14 (57) |

6 (43) |

4 (39) |

13 (55) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 39 (1.5) |

69 (2.7) |

51 (2.0) |

9 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

6 (0.2) |

36 (1.4) |

60 (2.4) |

270 (10.6) |

| Average precipitation days | 10 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 12 | 65 |

| Source: World Weather Online (2000-2012)[71] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Zakho | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

12.2 (54.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

29.1 (84.4) |

36.2 (97.2) |

40.4 (104.7) |

40.0 (104.0) |

35.7 (96.3) |

27.9 (82.2) |

19.4 (66.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

25.1 (77.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) |

3.1 (37.6) |

6.1 (43.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.2 (73.8) |

19.2 (66.6) |

13.7 (56.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

3.9 (39.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 144 (5.7) |

136 (5.4) |

129 (5.1) |

109 (4.3) |

43 (1.7) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.0) |

27 (1.1) |

83 (3.3) |

127 (5.0) |

799 (31.6) |

| Source: [72] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Assyrian populations are distributed between the Assyrian homeland and the Assyrian diaspora. There are no official statistics, and estimates vary greatly, between less than one million in the Assyrian homeland,[3] and 3.3 million with the diaspora included,[73] mostly due to the uncertainty of the number of Assyrians in Iraq and Syria. Since the 2003 Iraq War, Iraqi Assyrians have been displaced into Syria in significant but unknown numbers. Since the Syrian Civil War began in 2011, Syrian Assyrians have been displaced into Turkey in significant but unknown numbers. The indigenous Assyrian homeland areas are "part of today's northern Iraq, southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran and northeastern Syria".[74]

The Assyrian communities that are still left in the Assyrian homeland are in Syria (400,000),[75] Iraq (300,000),[76] Iran (20,000),[77][78] and Turkey (15,000–25,100).[77][79] Most of the Assyrians living in Syria today, in the Al Hasakah Governorate in villages along the Khabur river, descend from refugees that arrived there after the Assyrian genocide and Simele massacre of the 1910s and 30s. Christian communities of Oriental Orthodox Syriacs lived in Tur Abdin, an area in Southeastern Turkey, Nestorian Assyrians lived in the Hakkari Mountains, which straddles the border of northern Iraq and Southern Turkey, as well as the Urmia Plain, an area located on the western bank of Lake Urmia, and Chaldean and Syriac Catholics lived in the Nineveh Plains, an area located in Northern Iraq.[80]

More than half of Iraqi Christians have fled to neighboring countries since the start of the Iraq War, and many have not returned, although a number are migrating back to the traditional Assyrian homeland in the Kurdish Autonomous region.[81] Most Assyrians nowadays live in northern Iraq, with the community in Northern (Turkish) Hakkari being completely decimated, and the ones in Tur Abdin and Urmia Plain are largely depopulated.[1]

Creation of an Assyrian autonomous province

The Assyrian-inhabited towns and villages on the Nineveh Plain form a concentration of those belonging to Syriac Christian traditions, and since this area is the ancient home of the Assyrian empire through which the Assyrian people trace their cultural heritage, the Nineveh Plain is the area on which an effort to form an autonomous Assyrian entity has become concentrated. There have been calls by some politicians inside and outside Iraq to create an autonomous region for Assyrian Christians in this area.[82][83]

In the Transitional Administrative Law adopted in March 2004 in Baghdad, not only were provisions made for the preservation of Assyrian culture through education and media, but a provision for an administrative unit also was accepted. Article 125 in Iraq's Constitution states that: "This Constitution shall guarantee the administrative, political, cultural, and educational rights of the various nationalities, such as Turkomen, Chaldeans, Assyrians, and all other constituents, and this shall be regulated by law."[84][85]

On January 21, 2014, the Iraqi government had declared that Nineveh Plains would become a new province, which would serve as a safe haven for Assyrians.[86] After the liberation of the Nineveh Plain from ISIL between 2016/17, all Assyrian political parties called on the European Union and UN Security Council for the creation of an Assyrian self-administered province in the Nineveh Plain.[87]

Between the 28th-30 June 2017, a conference was held in Brussels dubbed, The Future for Christians in Iraq.[88] The conference was organised by the European People's Party and had participants extending from Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac organizations, including representatives from the Iraqi government and the KRG. The conference was boycotted by the Assyrian Democratic Movement, Sons of Mesopotamia, Assyrian Patriotic Party, Chaldean Catholic Church and Assyrian Church of the East. A position paper was signed by the remaining political organizations involved.[89]

See also

- Assur

- Nineveh Plains

- Beth Nahrain

- Hakkari

- List of Assyrian settlements

- Persian Assyria

- Tur Abdin

- Asōristān

- Kurdistan

References

- ^ أ ب The Origins of War: From the Stone Age to Alexander the Great By Arther Ferrill – p. 70

- ^ Odisho, Devi (February 12, 2016). "Canada and the Future of Assyria". Foreign Policy Journal. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ أ ب Carl Skutsch (2013). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-135-19388-1.

- ^ Macuch, R. (1987). “ASSYRIANS IN IRAN i. The Assyrian community (Āšūrīān) in Iran.” Encyclopædia Iranica, II/8. pp. 817-822

- ^ 2000, p. 58

- ^ p. 32

- ^ p.

- ^ "Assyrians: "3,000 Years of History, Yet the Internet is Our Only Home"". www.culturalsurvival.org (in الإنجليزية). 30 March 2022. Retrieved 2022-11-06.

- ^ "The Issue of An Assyrian Homeland". Seyfocenter (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2020-03-06. Retrieved 2022-11-06.

- ^ For Assyrians as a Christian people, see

- Joel J. Elias, The Genetics of Modern Assyrians and their Relationship to Other People of the Middle East

- Steven L. Danver, Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues, p. 517

- ^ Y Odisho, George (1998). The sound system of modern Assyrian (Neo-Aramaic). Harrowitz. p. 8. ISBN 3-447-02744-4.

- ^ "Nineveh". Max Mallowan. 9 July 2023.

- ^ Bertman, Stephen (2003). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-019-518364-1. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ J. A. Brinkman (2001). "Assyria". In Bruce Manning Metzger, Michael David Coogan (ed.). The Oxford companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. p. 63.

- ^ Biblical Archaeology Review May/June 2001: Where Was Abraham's Ur? by Allan R. Millard

- ^ Société des études arméniennes, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Association de la revue des études arméniennes (1989). Revue des études arméniennes, Volume 21. pp. 303, 309.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ NAARDA, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854)

- ^ Brock, Sebastian P. (2005). "The Syriac Orient: A Third 'Lung' for the Church?". Orientalia Christiana Periodica. 71: 5–20.

- ^ Parpola, Simo. "ASSYRIAN IDENTITY IN ANCIENT TIMES AND TODAY" (PDF).

- ^ Fuller, 1864, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Hill, Henry, ed (1988). Light from the East: A Symposium on the Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian Churches. Toronto, Canada. pp. 108–109

- ^ "History of Ashur". Assur.de. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Massacres, Resistance, Protectors: Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern Anatolia during World War I By David Gaunt – p. 9, map p. 10.

- ^ Islamic desk reference, E. J. van Donzel

- ^ A modern history of the Kurds, David McDowall

- ^ Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (8 December 2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-134-43019-2.

- ^ Eckart Frahm (24 March 2017). A Companion to Assyria. Wiley. p. 1132. ISBN 978-1-118-32523-0.

- ^ Joseph, John (July 3, 2000). The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East: A History of Their Encounter with Western Christian Missions, Archaeologists, and Colonial Powers. BRILL. ISBN 9004116419 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Fred Aprim, "Assyria and Assyrians Since the 2003 US Occupation of Iraq"" (PDF). Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (8 December 2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-134-43019-2.

- ^ Eckart Frahm (24 March 2017). A Companion to Assyria. Wiley. p. 1132. ISBN 978-1-118-32523-0.

- ^ Joseph, John (July 3, 2000). The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East: A History of Their Encounter with Western Christian Missions, Archaeologists, and Colonial Powers. BRILL. ISBN 9004116419 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Fred Aprim, "Assyria and Assyrians Since the 2003 US Occupation of Iraq"" (PDF). Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Gallagher, Edmon Louis (23 March 2012). Hebrew Scripture in Patristic Biblical Theory: Canon, Language, Text. BRILL. pp. 123, 124, 126, 127, 139. ISBN 978-90-04-22802-3.

- ^ Julius Fürst (1867). A Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament: With an Introduction Giving a Short History of Hebrew Lexicography. Tauchnitz.

- ^ Wilhelm Gesenius; Samuel Prideaux Tregelles (1859). Gesenius's Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament Scriptures. Bagster.

- ^ Benjamin Davies (1876). A Compendious and Complete Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament, Chiefly Founded on the Works of Gesenius and Fürst ... A. Cohn.

- ^ Coakley, J. F. (2011). Brock, Sebastian P.; Butts, Aaron M.; Kiraz, George A.; van Rompay, Lucas (eds.). Chaldeans. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-59333-714-8.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Council of Basel-Ferrara-Florence, 1431-49 A.D.

- ^ Braun-Winkler, p. 112

- ^ Michael Angold; Frances Margaret Young; K. Scott Bowie (17 August 2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 5, Eastern Christianity. Cambridge University Press. p. 527. ISBN 978-0-521-81113-2.

- ^ Wilhelm Braun, Dietmar W. Winkler, The Church of the East: A Concise History (RoutledgeCurzon 2003), p. 83

- ^ Ainsworth, William (1841). "An Account of a Visit to the Chaldeans, Inhabiting Central Kurdistán; and of an Ascent of the Peak of Rowándiz (Ṭúr Sheïkhíwá) in Summer in 1840". The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 11. e.g. p. 36. doi:10.2307/1797632. JSTOR 1797632.

- ^ William F. Ainsworth, Travels and Researches in Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Chaldea and Armenia (London 1842), vol. II, p. 272, cited in John Joseph, The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East (BRILL 2000), pp. 2 and 4

- ^ Layard, Austen Henry (July 3, 1850). Nineveh and its remains: an enquiry into the manners and arts of the ancient assyrians. Murray. p. 260 – via Internet Archive.

Chaldaeans Nestorians.

- ^ Simon (oratorien), Richard (July 3, 1684). "Histoire critique de la creance et des coûtumes des nations du Levant". Chez Frederic Arnaud – via Google Books.

- ^ Southgate, Horatio (July 3, 1844). Narrative of a Visit to the Syrian [Jacobite] Church of Mesopotamia. D. Appleton. p. 141 – via Internet Archive.

southgate papal chaldean.

- ^ Abul Fazl-i-Ạllámí (1894), "Description of the Earth", The Áin I Akbarí, III, Translated by H.S. Jarrett, Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press for the Asiatic Society of Bengal, pp. 25–27, https://books.google.com/books?id=81AmAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA26.

- ^ Wright, William (1894). A short history of Syriac literature. Adam and Charles Black. ISBN 9780837076799. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ "Ottoman Empire | Facts, History, & Map | Britannica". www.britannica.com (in الإنجليزية). 2023-07-03. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- ^ David Gaunt, "The Assyrian Genocide of 1915", Assyrian Genocide Research Center, 2009

- ^ Akçam, Taner (2012). The Young Turks' Crime against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. pp. xx–xxi. ISBN 978-1-4008-4184-4. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ Genocide Scholars Association Officially Recognizes Assyrian Greek Genocides. 16 December 2007. Retrieved 2010-02-02

- ^ Khosoreva, Anahit. "The Assyrian Genocide in the Ottoman Empire and Adjacent Territories" in The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. Ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2007, pp. 267–274. ISBN 1-4128-0619-4.

- ^ Travis, Hannibal. "Native Christians Massacred: The Ottoman Genocide of the Assyrians During World War I." Genocide Studies and Prevention, Vol. 1, No. 3, December 2006.

- ^ "Mar Narsi church – Dhouk". www.ishtartv.com.

- ^ Khan, Geoffrey (16 June 2018). The Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Barwar. BRILL. ISBN 9789004167650 – via Google Books.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Ashur (Qal'at Sherqat)". whc.unesco.org.

- ^ أ ب Griffis, Margaret (19 January 2017). "Militants Execute Civilians in Mosul; 101 Killed Across Iraq". Antiwar.com. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ "Relief Projects - Assyrian Aid Society - Iraq". www.assyrianaidiraq.org.

- ^ "Assyrian Aid Society of America". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- ^ Chulov, Martin; Hawramy, Fazel (9 August 2014). "'Isis has shattered the ancient ties that bound Iraq's minorities'". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Barnes, Julian E.; Sparshott, Jeffrey; Malas, Nour (8 August 2014). "Barack Obama Approves Airstrikes on Iraq, Airdrops Aid". Wall Street Journal – via online.wsj.com.

- ^ "Aiding the Assyrians Fight Against ISIS". The Huffington Post. 2015-04-15. Retrieved 2016-05-02.

- ^ "ISIL video shows destruction of Mosul artefacts", Al Jazeera, 27 Feb 2015

- ^ Buchanan, Rose Troup and Saul, Heather (25 February 2015) Isis burns thousands of books and rare manuscripts from Mosul's libraries The Independent

- ^ "Assyrian Militia in Iraq Battles Against ISIS for Homeland". www.aina.org. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- ^ Alkhshali, Hamdi; Smith-Spark, Laura; Lister, Tim (22 October 2016). "ISIS kills hundreds in Mosul area, source says". CNN. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "Iraqi residents flee Islamic State-held town of Tel Keyf". YouTube. Reuters. 10 January 2017. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Shaqlawa". Ishtar Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "Tel Kaif, Ninawa Monthly Climate Average, Iraq". World Weather Online. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ "Climate: zakho". Climate-Data. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ "UNPO: Assyria". www.unpo.org. 2 November 2009.

- ^ Donabed, Sargon (2015). Reforging a Forgotten History: Iraq and the Assyrians in the Twentieth Century. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-8605-6.

- ^ "Syria's Assyrians threatened by extremists – Al-Monitor: the Pulse of the Middle East". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "مسؤول مسيحي : عدد المسيحيين في العراق تراجع الى ثلاثمائة الف". Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ أ ب "Ishtar: Documenting The Crisis In The Assyrian Iranian Community". aina.org.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2010-10-13). "Iran: Last of the Assyrians". Refworld. Retrieved 2013-09-18.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld – World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Turkey : Assyrians". Refworld.

- ^ Rev. W.A. Wigram (1929). The Assyrians and Their Neighbours. London.

- ^ Assyria. UNPO (2008-03-25). Retrieved on 2013-12-08.

- ^ Iraqi Christians hold critical meeting Archived 2011-07-04 at the Wayback Machine, The Kurdish Globe

- ^ Dutch MP calls for autonomous Assyrian Christian region in north Iraq, AKI

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-14. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Iraq Sustainable Democracy Project". Iraqdemocracyproject.org. 2008-02-19. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ BetBasoo, Peter; Nuri Kino (22 January 2014). "Will a Province for Assyrians Stop Their Exodus From Iraq?". Assyrian International News Agency. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ "Iraqi Christians ask EU to support the creation of a Nineveh Plain Province". Archived from the original on 2020-11-17. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- ^ "christians-in-iraq". christians-in-iraq. Archived from the original on 2018-08-29. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- ^ "The Future of the Nineveh Plain - Government - Politics". Scribd.

External links

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing سريانية الكلاسيكية-language text

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the symbol caption or type parameters

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Regions of Iraq

- Geography of the Middle East

- Cultural regions

- Mesopotamia

- Geography of Iraq

- Geography of Turkey

- Geography of Syria

- Geography of Iran

- Historical regions

- Levant

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Assyrian irredentism