يوكيو ميشيما

- الصيغة الأصلية لهذا الاسم الشخصي هي Mishima Yukio. هذه المقالة تستخدم الترتيب الغربي للأسماء.

Yukio Mishima | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

三島由紀夫 | |||||

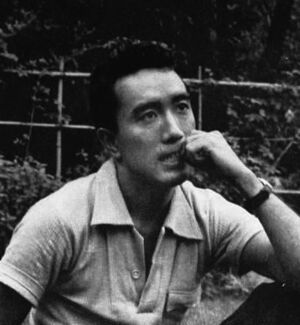

Mishima in 1956 | |||||

| وُلِدَ | Kimitake Hiraoka 14 يناير 1925 | ||||

| توفي | 25 نوفمبر 1970 (aged 45)

| ||||

| سبب الوفاة | الانتحار بطريقة Seppuku | ||||

| المثوى | Tama Cemetery, Tokyo | ||||

| المدرسة الأم | جامعة طوكيو | ||||

| المهنة |

| ||||

العمل البارز | اعترافات قناع، معبد المقصورة الذهبية، بحر الخصوبة | ||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 三島 由紀夫 | ||||

| Hiragana | みしま ゆきお | ||||

| Katakana | ミシマ ユキオ | ||||

| |||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 平岡 公威 | ||||

| Hiragana | ひらおか きみたけ | ||||

| Katakana | ヒラオカ キミタケ | ||||

| |||||

| التوقيع | |||||

| |||||

يوكيو ميشيما (三島 由紀夫, Mishima Yukio) كان الاسم المسستعار للكاتب كيميتاكى هيراؤكا (平岡 公威, Hiraoka Kimitake, 14 يناير 1925–25 نوفمبر 1970)، مؤلف وشاعر وكاتب مسرحيات ياباني، يـُذكر أيضاً لانتحاره الطقسي بواسطة سـِپـّوكو seppuku.

كانت أعماله تمجد تقاليد محاربي الساموراي القدامى. ولأنه كان ينتقد القيم الديمقراطية الحديثة، فقد أقدم على الانتحار مع رفيق له متبعًا طقوس الساموراي المعروفة باسم سپوكو.

سمي يوكيو ميشيما عند ولادته باسم هيراوكا كيميتاكي، وامتهن المحاماة في طوكيو. ونُشرت أول قصة له عام 1944م. والتحق بالخدمة المدنية في وقت لاحق. وفي عام 1949 نشر رواية بعنوان اعترافات قناع. ومن ضمن رواياته الأخرى: صوت الأمواج (1954م)؛ معبد المقصورة الذهبية (1956). وقد عالج هذان الكتابان موضوعي الموت العنيف والجمال.

أسس ميشيما عام 1968م جمعية الدرع التي كرسها لروح الساموراي. وصار خبيرًا في الفنون القتالية للكراتيه والكيندو. وبعد إنهائه لرواية بحر الخصوبة التي استغرقت كتابتها الفترة ما بين عامي 1965 و1970، دخل ميشيما إلى مقر القيادة العسكرية في طوكيو، وانتحر.

محاولة الانقلاب والانتحار الطقسي

In August 1966, Mishima visited Ōmiwa Shrine in Nara Prefecture, thought to be one of the oldest Shintō shrines in Japan, as well as the hometown of his mentor Zenmei Hasuda and the areas associated with the Shinpūren Rebellion (神風連の乱, Shinpūren no ran), an uprising against the Meiji government by samurai in 1876. This trip would become the inspiration for portions of Runaway Horses (奔馬, Honba), the second novel in the Sea of Fertility tetralogy. While in Kumamoto, Mishima purchased a Japanese sword for 100,000 yen. Mishima envisioned the reincarnation of Kiyoaki, the protagonist of the first novel Spring Snow, as a man named Isao who put his life on the line to bring about a restoration of direct rule by the Emperor against the backdrop of the League of Blood Incident (血盟団事件, Ketsumeidan jiken) in 1932.

From 12 April to 27 May 1967, Mishima underwent basic training with the Ground Self-Defense Force (GSDF).[2] Mishima had originally lobbied to train with the GSDF for six months, but was met with resistance from the Defense Agency.[2] Mishima's training period was finalized to 46 days, which required using some of his connections.[2] His participation in GSDF training was kept secret, both because the Defense Agency did not want to give the impression that anyone was receiving special treatment, and because Mishima wanted to experience "real" military life.[2][3] As such, Mishima trained under his birth name, Kimitake Hiraoka, and most of his fellow soldiers did not recognize him.[2]

From June 1967, Mishima became a leading figure in a plan to create a 10,000-man "Japan National Guard" (祖国防衛隊, Sokoku Bōeitai) as a civilian complement to Japan's Self Defense Forces. He began leading groups of right-wing college students to undergo basic training with the GDSF in the hope of training 100 officers to lead the National Guard.[4][5][3]

Like many other right-wingers, Mishima was especially alarmed by the riots and revolutionary actions undertaken by radical "New Left" university students, who took over dozens of college campuses in Japan in 1968 and 1969. On 26 February 1968, the 32nd anniversary of the February 26 Incident, he and several other right-wingers met at the editorial offices of the recently founded right-wing magazine Controversy Journal (論争ジャーナル, Ronsō jaanaru), where they pricked their little fingers and signed a blood oath promising to die if necessary to prevent a left-wing revolution from occurring in Japan.[6][7] Mishima showed his sincerity by signing his birth name, Kimitake Hiraoka, in his own blood.[6][7]

When Mishima found that his plan for a large-scale Japan National Guard with broad public and private support failed to catch on,[8] he formed the Tatenokai (楯の会, "Shield Society") on 5 October 1968, a private militia composed primarily of right-wing college students who swore to protect the Emperor of Japan. The activities of the Tatenokai primarily focused on martial training and physical fitness, including traditional kendo sword-fighting and long-distance running.[9][10] Mishima personally oversaw this training himself. Initial membership was around 50, and was drawn primarily from students from Waseda University and individuals affiliated with Controversy Journal. The number of Tatenokai members later increased to 100.[11][4] Some of the members had graduated from university and were employed, while some were already working adults when they enlisted.[12]

On 25 November 1970, Mishima and four members of the Tatenokai—Masakatsu Morita (森田必勝), Masahiro Ogawa (小川正洋), Masayoshi Koga (小賀正義), and Hiroyasu Koga (古賀浩靖)—used a pretext to visit the commandant Kanetoshi Mashita (益田兼利) of Camp Ichigaya, a military base in central Tokyo and the headquarters of the Eastern Command of the Japan Self-Defense Forces.[13] Inside, they barricaded the office and tied the commandant to his chair. Mishima wore a white hachimaki headband with a red hinomaru circle in the center bearing the kanji for "To be reborn seven times to serve the country" (七生報國, Shichishō hōkoku), which was a reference to the last words of Kusunoki Masasue, the younger brother of the 14th century imperial loyalist samurai Kusunoki Masashige (楠木正成), as the two brothers died fighting to defend the Emperor.[14] With a prepared manifesto and a banner listing their demands, Mishima stepped out onto the balcony to address the soldiers gathered below. His speech was intended to inspire a coup d'état to restore the power of the emperor. He succeeded only in irritating the soldiers, and was heckled, with jeers and the noise of helicopters drowning out some parts of his speech. In his speech Mishima rebuked the JSDF for their passive acceptance of a constitution that "denies (their) own existence" and shouted to rouse them, "Where has the spirit of the samurai gone?" In his final written appeal that Morita and Ogawa scattered copies of from the balcony, Mishima expressed his dissatisfaction with the half-baked nature of the JSDF:

It is self-evident that the United States would not be pleased with a true Japanese volunteer army protecting the land of Japan.[15][16]

After he finished reading his prepared speech in a few minutes' time, Mishima cried out "Long live the Emperor!" (天皇陛下万歳, Tenno-heika banzai) three times. He then retreated into the commandant's office and apologized to the commandant, saying,

"We did it to return the JSDF to the Emperor. I had no choice but to do this."[17][18][19]

Mishima then committed seppuku, a form of ritual suicide by disembowelment associated with the samurai. Morita had been assigned to serve as Mishima's second (kaishakunin), cutting off his head with a sword at the end of the ritual to spare him unnecessary pain. However, Morita proved unable to complete his task, and after three failed attempts to sever Mishima's head, Koga had to step in and complete the task.[17][18][19]

According to the testimony of the surviving coup members, originally all four Tatenokai members had planned to commit seppuku along with Mishima. However Mishima attempted to dissuade them and three of the members acquiesced to his wishes. Only Morita persisted, saying, "I can't let Mr. Mishima die alone." But Mishima knew that Morita had a girlfriend and still hoped he might live. Just before his seppuku, Mishima tried one more time to dissuade him, saying "Morita, you must live, not die."[20][21][أ] Nevertheless, after Mishima's seppuku, Morita knelt and stabbed himself in the abdomen and Koga acted as kaishakunin again.[22]

This coup attempt is called The Mishima Incident (三島事件, Mishima jiken) in Japan.[ب]

Another traditional element of the suicide ritual was the composition of so-called death poems by the Tatenokai members before their entry into the headquarters.[24] Having been enlisted in the Ground Self-Defense Force for about four years, Mishima and other Tatenokai members, alongside several officials, were secretly researching coup plans for a constitutional amendment. They thought there was a chance when security dispatch (治安出動, Chian Shutsudo) was dispatched to subjugate the Zenkyoto revolt. However, Zenkyoto was suppressed easily by the Riot Police Unit in October 1969. These officials gave up the coup of constitutional amendment, and Mishima was disappointed in them and the actual circumstances in Japan after World War II.[25] Officer Kiyokatsu Yamamoto (山本舜勝), Mishima's training teacher, explained further:

The officers had a trusty connection with the U.S.A.F. (includes U.S.F.J), and with the approval of the U.S. army side, they were supposed to carry out a security dispatch toward the Armed Forces of the Japan Self-Defense Forces. However, due to the policy change (reversal) of U.S. by Henry Kissinger who prepared for visiting China in secret (changing relations between U.S. and China), it became a situation where the Japanese military was not allowed legally.[25]

Mishima planned his suicide meticulously for at least a year and no one outside the group of hand-picked Tatenokai members knew what he was planning.[26][27] His biographer, translator John Nathan, suggests that the coup attempt was only a pretext for the ritual suicide of which Mishima had long dreamed.[28] His friend Scott-Stokes, another biographer, says that "Mishima is the most important person in postwar Japan", and described the shackles of the constitution of Japan:

Mishima cautioned against the lack of reality in the basic political controversy in Japan and the particularity of Japan's democratic principles.[29]

Scott-Stokes noted a meeting with Mishima in his diary entry for 3 September 1970, at which Mishima, with a dark expression on his face, said:

Japan lost its spiritual tradition, and materialism infested instead. Japan is under the curse of a Green Snake now. The Green Snake bites on Japanese chest. There is no way to escape this curse.[30]

Scott-Stokes told Takao Tokuoka in 1990 that he took the Green Snake to mean the U.S. dollar.[31] Between 1968 and 1970, Mishima also said words about Japan's future. Mishima's senior friend and father heard from Mishima:

Japan will be hit hard. One day, the United States suddenly contacts China over Japan's head, Japan will only be able to look up from the bottom of the valley and eavesdrop on the conversation slightly. Our friend Taiwan will say that "it will no longer be able to count on Japan", and Taiwan will go somewhere. Japan may become an orphan in the Orient, and may eventually fall into the product of slave dealers.[32]

Mishima's corpse was returned home the day after his death. His father Azusa had been afraid to see his son whose appearance had completely changed. However, when he looked into the casket fearfully, Mishima's head and body had been sutured neatly, and his dead face, to which makeup had been beautifully applied, looked as if he were alive due to the police officers. They said: "We applied funeral makeup carefully with special feelings, because it is the body of Dr. Mishima, whom we have always respected secretly."[33] Mishima's body was dressed in the Tatenokai uniform, and the guntō was firmly clasped at the chest according to the will that Mishima entrusted to his friend Kinemaro Izawa (伊沢甲子麿).[33][34] Azusa put the manuscript papers and fountain pen that his son cherished in the casket together.[33][ت] Mishima had made sure his affairs were in order and left money for the legal defence of the three surviving Tatenokai members—Masahiro Ogawa (小川正洋), Masayoshi Koga (小賀正義), and Hiroyasu Koga.[27][ث] After the incident, there were exaggerated media commentaries that "it was a fear of the revival of militarism".[31][38] The commandant who was made a hostage said in the trial,

I didn't feel hate towards the defendants at that time. Thinking about the country of Japan, thinking about the JSDF, the pure hearts of thinking about our country that did that kind of thing, I want to buy it as an individual.[17]

The day of the Mishima Incident (25 November) was the date when Hirohito (Emperor Shōwa) became regent and the Emperor Shōwa made the Humanity Declaration at the age of 45. Researchers believe that Mishima chose that day to revive the "God" by dying as a scapegoat, at the same age as when the Emperor became a human.[39][40] There are also views that the day corresponds to the date of execution (after the adoption of the Gregorian calendar) of Yoshida Shōin (吉田松陰), whom Mishima respected,[33] or that Mishima had set his period of bardo (中有, Chuu) for reincarnation because the 49th day after his death was his birthday, 14 January.[41] On his birthday, Mishima's remains were buried in the grave of the Hiraoka Family at Tama Cemetery.[33] In addition, 25 November is the day he began writing Confessions of a Mask (仮面の告白, Kamen no kokuhaku), and this work was announced as "Techniques of Life Recovery", "Suicide inside out". Mishima also wrote down in notes for this work,

This book is a will for leave in the Realm of Death where I used to live. If you take a movie of a suicide jumped, and rotate the film in reverse, the suicide person jumps up from the valley bottom to the top of the cliff at a furious speed and he revives.[42][43]

Writer Takashi Inoue believes he wrote Confessions of a Mask to live in postwar Japan, and to get away from his "Realm of Death"; by dying on the same date that he began to write Confessions of a Mask, Mishima intended to dismantle all of his postwar creative activities and return to the "Realm of Death" where he used to live.[43]

الشريط المسجل قبل انتحاره بتسعة أشهر

تم الكشف يوم الخميس 12 يناير 2017 على تسجيل صوتي مؤخرا في محطة تلفزيون TBS للمؤلف الياباني ميشيما يوكيو يتحدث فيه عن إحساسه بقرب نهايته قبل تسعة أشهر من انتحاره. الشريط الذي تبلغ مدته 80 دقيقة يحتوي على حوار بين ميشيما ومترجم بريطاني يدعى جون بيستر في 19 فبراير 1970 تقريبا. قال ميشيما في الشريط ”أشعر بأن الموت يتسرب إلى جسدي“. وله تصريح يتنبأ فيه بمحاولة الانقلاب الفاشلة قائلا ”أشعر بالاحباط تجاه ما أصبحت عليه اليابان حاليا ولا أجد لديّ طريقا لتصحيح الأوضاع سوى بالكتابة“. وقال منتقدا كتاباته ”الخلل في أعمالي يكمن في أن الهياكل درامتيكية بشكل كبير. فأنا أصيغ أعمالي مثل اللوحات الزيتية. أنا أكره الصور على الطريقة اليابانية، التي تترك مساحة فارغة“. كان لديه تحفظ على الدستور الياباني. كان عنوان الشريط ”خواطر قبل انتحاره“ وصنف على أنه ”غير مخصص للبث“. ولم يكن يعلم معظم العاملين بالمحطة بوجود هذا التسجيل. قال ياماناكا تاكيشي، وهو زميل باحث في متحف ميشيما يوكيو الأدبي ”يظهر التسجيل أنه كان يخطط بوضوح للأحداث التي قادته للانتحار. لم أكن أعرف أنه قارن الخلل في كتبه باللوحات الزيتية“.[44]

أهم أعماله

| Japanese Title | English Title | Year | English translation, year | ISBN |

| 假面の告白 Kamen no Kokuhaku |

Confessions of a Mask | 1948 | Meredith Weatherby, 1958 | ISBN 0-8112-0118-X |

| 愛の渇き Ai no Kawaki |

Thirst for Love | 1950 | Alfred H. Marks, 1969 | ISBN 4-10-105003-1 |

| 禁色 Kinjiki |

Forbidden Colors | 1953 | Alfred H. Marks, 1968–1974 | ISBN 0-375-70516-3 |

| 潮騷 Shiosai |

The Sound of Waves | 1954 | Meredith Weatherby, 1956 | ISBN 0-679-75268-4 |

| 金閣寺 Kinkaku-ji* |

The Temple of the Golden Pavilion | 1956 | Ivan Morris, 1959 | ISBN 0-679-75270-6 |

| 鏡子の家 Kyōko no Ie |

Kyoko's House | 1959 | ISBN | |

| 宴のあと Utage no Ato |

After the Banquet | 1960 | Donald Keene, 1963 | ISBN 0-399-50486-9 |

| 午後の曳航 Gogo no Eikō |

The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea | 1963 | John Nathan, 1965 | ISBN 0-679-75015-0 |

| 絹と明察 Kinu to Meisatsu |

Silk and Insight | 1964 | Hiroaki Sato, 1998 | ISBN 0-7656-0299-7 |

| 三熊野詣 Mikumano Mōde (short story) |

Acts of Worship | 1965 | John Bester, 1995 | ISBN 0-87011-824-2 |

| サド侯爵夫人 Sado Kōshaku Fujin (play) |

Madame de Sade | 1965 | Donald Keene, 1967 | ISBN 0-394-17304-X |

| 憂國 Yūkoku (short story) |

Patriotism | 1966 | Geoffrey W. Sargent, 1966 | ISBN 0-8112-1312-9 |

| 真夏の死 Manatsu no Shi |

Death in Midsummer and other stories | 1966 | Edward G. Seidensticker, Ivan Morris, Donald Keene, Geoffrey W. Sargent, 1966 |

ISBN 0-8112-0117-1 |

| 葉隠入門 Hagakure Nyūmon |

Way of the Samurai | 1967 | Kathryn Sparling, 1977 | ISBN 0-465-09089-3 |

| わが友ヒットラー Waga Tomo Hittorā (play) |

My Friend Hitler and Other Plays | 1968 | Hiroaki Sato, 2002 | ISBN 0-231-12633-6 |

| 太陽と鐡 Taiyō to Tetsu |

Sun and Steel | 1970 | John Bester | ISBN 4-7700-2903-9 |

| 豐饒の海 Hōjō no Umi |

The Sea of Fertility tetralogy: | 1964- 1970 |

ISBN 0-677-14960-3 | |

| I. 春の雪 Haru no Yuki |

1. Spring Snow | 1968 | Michael Gallagher, 1972 | ISBN 0-394-44239-3 |

| II. 奔馬 Honba |

2. Runaway Horses | 1969 | Michael Gallagher, 1973 | ISBN 0-394-46618-7 |

| III. 曉の寺 Akatsuki no Tera |

3. The Temple of Dawn | 1970 | E. Dale Saunders and Cecilia S. Seigle, 1973 | ISBN 0-394-46614-4 |

| IV. 天人五衰 Tennin Gosui |

4. The Decay of the Angel | 1970 | Edward Seidensticker, 1974 | ISBN 0-394-46613-6 |

*For the temple called Kinkaku-ji, see Kinkaku-ji.

الأفلام

| Year | Title | USA Release Title(s) | Character | Director |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 純白の夜 Jumpaku no Yoru |

Unreleased in the U.S. | Hideo Ōba | |

| 1959 | 不道徳教育講座 Fudōtoku Kyōikukōza |

Unreleased in the U.S. | himself | Katsumi Nishikawa |

| 1960 | からっ風野郎 Karakkaze Yarō |

Afraid to Die | Takeo Asahina | Yasuzo Masumura |

| 1966 | 憂国 Yūkoku |

The Rite of Love and Death Patriotism |

Shinji Takeyama | Domoto Masaki, Yukio Mishima |

| 1968 | 黒蜥蝪 Kurotokage |

Black Lizard | Human Statue | Kinji Fukasaku |

| 1969 | 人斬り Hitokiri |

Tenchu! | Shimbei Tanaka | Hideo Gosha |

| 1985 | Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters |

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters | Paul Schrader Music by Philip Glass | |

| The Strange Case of Yukio Mishima (BBC documentary) |

The Strange Case of Yukio Mishima | Michael Macintyre |

انظر أيضاً

- Hachinoki kai – a chat circle to which Mishima belonged.

- Japan Business Federation attack – an incident in 1977 involving four persons (including one former Tatenokai member) connected by the Mishima incident.

- Kosaburo Eto – Mishima states that he was impressed with the seriousness of Eto's self-immolation, "the most intense criticism of politics as a dream or art."[45]

- Kumo no kai – a literary movement group presided over by Kunio Kishida in 1950–1954, to which Mishima belonged.

- Mishima Yukio Prize – a literary award established in September 1987.

- Phaedo – the book Mishima had been reading in his later years.

- Suegen – a traditional authentic Japanese style restaurant in Shinbashi that is known as the last dining place for Mishima and four Tatenokai members (Masakatsu Morita, Hiroyasu Koga, Masahiro Ogawa, Masayoshi Koga).

ملاحظات

- ^ This is the survived member Masayoshi Koga (小賀正義)'s testimony.[21]

- ^ Immediately after the incident, Yasunari Kawabata rushed to the Ichigaya camp, but was unable to enter the commandant's room during on-the-spot investigation.[23](He said that the report of "Kawabata was admitted to the bloody death scene" was a fake news.[23])

- ^ Masakatsu Morita's corpse, like Mishima, his head and body had been sutured neatly. Then Morita's body was dressed in the shroud, the casket was taken over by his brother. After the cremation in Yoyogi, Shibuya, Morita's ashes returned to his hometown of Mie Prefecture.[35][36]

- ^ Mishima as a father arranged for the department store for his two children till they became adults to receive Christmas gifts every year after his death,[37] and asked the publisher to pay the long-term subscription fee for children's magazines in advance and deliver them every month.[32]

المراجع

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةbio-m1 - ^ أ ب ت ث ج Inose-e 2012, pp. 486

- ^ أ ب Muramatsu 1990, pp. 421–442

- ^ أ ب Suzuki 2005, pp. 9–29

- ^ Mishima, Yukio (1967). 祖国防衛隊 綱領草案 [Draft for platform of the Japan National Guard] (in اليابانية).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) collected in complete36 2003, p. 665 - ^ أ ب Inose-e 2012, pp. 540

- ^ أ ب Azusa 1996, pp. 165–205

- ^ Flanagan, Damian (2014). Yukio Mishima. Reaktion Books. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-78023-419-9.

- ^ Jannarone, Kimberly (2015). Vanguard Performance Beyond Left and Right. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-472-11967-7.

- ^ Murata 2015, pp. 71–95

- ^ Flanagan, Damian (2014). Yukio Mishima. Reaktion Books. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-78023-419-9.

- ^ Murata 2015, pp. 215–216

- ^ Kakutani, Michiko (15 September 1985). "Mishima: Film Examines an Affair with Death". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Inose-e 2012, p. 719

- ^ Mishima's An appeal (檄, Geki)(last Manifesto) on 25 November 1970 was collected in complete36 2003, pp. 402–406

- ^ Sugiyama 2007, pp. 185–219

- ^ أ ب ت Date 1972, pp. 109–116

- ^ أ ب Date 1972, pp. 117–122

- ^ أ ب Nakamura 2015, pp. 200–229

- ^ Ando 1998, pp. 319–331

- ^ أ ب Mochi 2010, pp. 171–172

- ^ "Japanese Stunned by Samurai-Style Suicide of Novelist Mishima". Chicago Tribune. 26 November 1970. p. 88. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ أ ب Kawabata, Yasunari (1971). 三島由紀夫 [Yukio Mishima]. Shincho Extra Edition Yukio Mishima Reader (in اليابانية). collected in Gunzo18 1990, pp. 229–231

- ^ Keene, Donald (1988). The Pleasures of Japanese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 62. ISBN 0-231-06736-4. OCLC 18068964.

- ^ أ ب Yamamoto 2001, pp. 119–149, 192–237

- ^ Nakamura 2015, pp. 137–198

- ^ أ ب Jurō 2005, pp. 157–184

- ^ Nathan, John. Mishima: A biography, Little Brown and Company: Boston/Toronto, 1974.

- ^ Scott-Stokes, Henry (1971). ミシマは偉大だったか [Was Mishima great]. Shokun(Bungeishunjū) (in اليابانية). collected in memorial 1999

- ^ Scott-Stokes 1985, pp. 25–27

- ^ أ ب Tokuoka 1999, pp. 238–269

- ^ أ ب Azusa 1996, pp. 103–164

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Azusa 1996, pp. 7–30

- ^ Date 1972, pp. 157–196

- ^ complete42 2005, pp. 330–334

- ^ Nakamura 2015, pp. 231–253

- ^ Kodama, Takaya (1970). 知られざる家庭人・三島由紀夫 [Unknown side of family man]. Josei Jishin (in اليابانية).

- ^ Date 1972, pp. 271–304

- ^ Ando 1998, pp. 233–331

- ^ Shibata 2012, pp. 231–267

- ^ Komuro 1985, pp. 199–230

- ^ Notes of Confessions of a Mask is collected in complete27 2003, pp. 190–191

- ^ أ ب Inoue 2010, pp. 245–250

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ Mishima, Yukio (1969). 若きサムラヒのために―政治について [Lectures for Young Samurai: about politics]. Pocket Punch Oh! (in اليابانية). collected in complete35 2003, pp. 58–60

وصلات خارجية

- The Mishima Yukio Cyber Museum In Japanese only

- Web page devoted to Yukio Mishima Page with some information about Mishima, but with pop-up windows and advertisements

- Yukio Mishima: A 20th Century Samurai

- Books and Writers bio

- Short bio with photo

- Mishima chronology, with links

- YUKIO MISHIMA: The Harmony of Pen and Sword Ceremony commemorating his 70th Birthday Anniversary

- Blood and Flowers: Purity of Action in The Sea of Fertility

- Film review of Yukoku (Patriotism)

- Mishima is interviewed in English on a range of subjects From a 1980s BBC documentary (9:02)

- Mishima is interviewed in English on the subject of Japanese Nationalism From Canadian Television (3:59)

- Headlessgod.com: An Online Tribute to Yukio Mishima (Mishima-related news, quotes, links)

- CS1 errors: requires URL

- CS1 uses اليابانية-language script (ja)

- CS1 اليابانية-language sources (ja)

- CS1 errors: empty citation

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Biography with signature

- يوكيو ميشيما

- مواليد 1925

- وفيات 1970

- Kabuki playwrights

- Noh playwrights

- كتاب دراما ومسرحيات يابانيون

- ناشطون يابانيون

- Japanese kendoka

- روائيون يابانيون

- كتاب قصة قصيرة يابانيون

- شعراء يابانيون

- Japanese government officials

- Seppuku from Meiji period to present

- Activists who committed suicide

- شعراء انتحروا

- كتاب انتحروا

- خريجو جامعة طوكيو

- أشخاص من طوكيو

- 1970s coups d'état and coup attempts

- 20th-century essayists

- 20th-century Japanese dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century Japanese male actors

- 20th-century Japanese novelists

- 20th-century Japanese short story writers

- 20th-century poets

- 20th-century pseudonymous writers

- Attempted coups in Japan

- Bisexual male actors

- Bisexual writers

- Conservatism in Japan

- Controversies in Japan

- Cultural critics

- وفيات بقطع الرأس

- Far-right politics in Japan

- Film controversies in Japan

- Imperial Japanese Army personnel of World War II

- Imperial Japanese Army soldiers

- Japanese activists

- Japanese anti-communists

- Japanese bodybuilders

- Japanese essayists

- Japanese film directors

- Japanese male karateka

- Japanese male models

- Japanese male short story writers

- Japanese nationalists

- Japanese poets

- Japanese psychological fiction writers

- Japanese social commentators

- LGBT people from Japan

- LGBT film directors

- LGBT models

- LGBT writers from Japan

- LGBT-related suicides

- Male actors from Tokyo

- Pantheists

- People from Shinjuku

- People of Shōwa-period Japan

- People of the Empire of Japan

- Social critics

- University of Tokyo alumni

- Yomiuri Prize winners

- Writers from Tokyo