مكافحة الإرهاب

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| الإرهاب |

|---|

مكافحة الإرهاب Counter-terrorism (وتُكتَب أيضاً counterterrorism)، وتُعرف أيضاً باسم مناهضة الإرهاب، تتضمن الممارسات و التكتيكات العسكرية والتقنيات والاستراتيجيات التي تستخدمها الحكومة والجيش وإنفاذ القانون والأعمال و وكالات الاستخبارات لمحاربة الإرهاب أو منعه. استراتيجية مكافحة الإرهاب هي خطة حكومية لاستخدام أدوات القوة الوطنية لتحييد الإرهابيين ومنظماتهم وشبكاتهم من أجل جعلهم غير قادرين على استخدام العنف لبث الخوف وإكراه الحكومة أو مواطنيها على الرد وفقاً لأهداف الإرهابيين.[1]

إذا كانت الإرهاب جزءاً من عصيان أوسع، فقد تستخدم مكافحة الإرهاب إجراءات مكافحة التمرد. تستخدم القوات المسلحة الأمريكية مصطلح الدفاع الداخلي الأجنبي للبرامج التي تدعم البلدان الأخرى في محاولات لقمع التمرد أو الفوضى أو التخريب أو لتقليل الظروف التي قد تتطور في ظلها هذه التهديدات للأمن.[2][3][4]

التاريخ

رداً على تصاعد حملة الإرهاب في بريطانيا التي نفذها المسلحون الأيرلنديون الفينيون في ثمانينيات القرن التاسع عشر، أنشأ وزير الداخلية، السير وليام هاركورت، أول وحدة لمكافحة الإرهاب على الإطلاق. فقد تم تشكيل الفرع الأيرلندي الخاص في البداية كقسم من دائرة المباحث الجنائية من شرطة لندن الكبرى في عام 1883، لمكافحة الإرهاب الجمهوري الأيرلندي من خلال التسلل والتخريب. [5]

تصور هاركورت وحدة دائمة مكرسة لمنع العنف ذي الدوافع السياسية من خلال استخدام التقنيات الحديثة مثل التسلل السري. كان هذا الفرع الرائد أول من تم تدريبه على تقنيات مكافحة الإرهاب.[6]

تم تغيير اسمها إلى الفرع الخاص حيث تم توسيع صلاحياتها تدريجياً[7]لتشمل دوراً عاماً في مكافحة الإرهاب ومكافحة التخريب الأجنبي والتسلل إلى الجريمة المنظمة. وقد أنشأت وكالات إنفاذ القانون وحدات مماثلة في بريطانيا وأماكن أخرى.[8]

توسعت قوات مكافحة الإرهاب مع التهديد المتزايد للإرهاب في أواخر القرن العشرين. على وجه التحديد، بعد هأحداث 11 سبتمبر 2001، مما جعلت الحكومات الغربية من جهود مكافحة الإرهاب أولوية، بما في ذلك المزيد من التعاون الخارجي، وتغيير التكتيكات التي تشمل الفريق الأحمر،[9] والتدابير الوقائية.[10] على الرغم من أن الهجمات المثيرة في العالم المتقدم تحظى بقدر كبير من الاهتمام الإعلامي،[11]تحدث معظم العمليات الإرهابية في البلدان الأقل نمواً.[12] وتؤدي ردود فعل الحكومات على الإرهاب، في بعض الحالات، إلى عواقب وخيمة غير مقصودة.[13]

التخطيط

المخابرات والمراقبة والاستطلاع

تتضمن معظم استراتيجيات مكافحة الإرهاب زيادة في الشرطة الضابطة والاستخبارات المحلية. الأنشطة المركزية التقليدية: اعتراض الاتصالات وتعقب الأشخاص. ومع ذلك، فقد وسعت التكنولوجيا الجديدة في نطاق العمليات العسكرية و تنفيذ القانون.

غالباً ما يتم توجيه الاستخبار الداخلي إلى مجموعات معينة، يتم تحديدها على أساس الأصل أو الدين، وهو ما يمثل مصدراً للجدل السياسي. تثير المراقبة الجماعية لسكان بأكمله اعتراضات على الحريات المدنية. غالباً ما يكون من الصعب اكتشاف الإرهابيون المحليون، وخاصة المهاجمون المنفردون، بسبب جنسيتهم أو وضعهم القانوني وقدرتهم على البقاء تحت الرادار.[14]

لتحديد الإجراء الفعال عندما يبدو الإرهاب حدثاً منفرداً، تحتاج المنظمات الحكومية المناسبة إلى فهم مصدر الجماعات الإرهابية ودوافعها وطرق إعدادها وتكتيكاتها. يعتبر الاستخبار الجيد في صميم هذا الإعداد، فضلاً عن الفهم السياسي والاجتماعي لأي مظالم يمكن حلها. من الناحية المثالية، يحصل المرء على معلومات من داخل المجموعة، وهو تحد صعب للغاية لـ الاستخبارات البشرية لأن الخلايا الإرهابية العملياتية غالباً ما تكون صغيرة، وجميع الأعضاء معروفين لبعضهم البعض، وربما حتى مرتبطين.[15]

تمثل مكافحة التجسس تحدياً كبيراً لأمن الأنظمة القائمة على الخلايا، نظراً لأن الهدف المثالي، ولكن شبه المستحيل، هو الحصول على مصدر سري داخل الخلية. يمكن أن يلعب التتبع المالي دوراً، باعتباره اعتراض الاتصالات. ومع ذلك، يجب أن يكون كلا النهجين متوازنين مع التوقعات المشروعة للخصوصية.[16]

السياق القانوني

استجابة للتشريعات المتزايدة.

- لدى المملكة المتحدة تشريعات لمكافحة الإرهاب منذ أكثر من ثلاثين عاما. صدر قانون منع العنف لعام 1939 رداً على حملة الجيش الجمهوري الأيرلندي (إيرا) من العنف في إطار خطة إس. سُمح لهذا القانون بالانتهاء في عام 1953. وألغي في عام 1973 ليحل محله قوانين منع الإرهاب، رداً على الاضطرابات في أيرلندا الشمالية. من عام 1974 إلى عام 1989، تم تجديد الأحكام المؤقتة للقانون سنوياً.

- في عام 2000، تم استبدال القوانين بقانون دائم قانون الإرهاب لعام 2000، والذي احتوى على العديد من صلاحياتها، ثم قانون منع الإرهاب لعام 2005.

- تم تقديم قانون الأمن ومكافحة الإرهاب والجريمة لعام 2001 رسمياً إلى البرلمان في 19 نوفمبر 2001، بعد شهرين من هأحداث 11 سبتمبر 2001 في الولايات المتحدة. وقد حصل على الموافقة الملكية ودخل حيز التنفيذ في 13 ديسمبر 2001. وفي 16 ديسمبر 2004، حكم مجلس اللوردات بأن الجزء الرابع يتعارض مع الاتفاقية الأوروبية لحقوق الإنسان. ومع ذلك، بموجب قانون حقوق الإنسان عام 1998، ظل ساري المفعول. تمت صياغة قانون منع الإرهاب لعام 2005 للرد على حكم لوردات القانون و قانون الإرهاب لعام 2006 ينشئ جرائم جديدة تتعلق بالإرهاب، ويعدل الجرائم القائمة. تمت صياغة القانون في أعقاب تفجيرات لندن 7 يوليو 2005، ومثل سابقاتها، أثبتت بعض شروطه أنها مثيرة للجدل إلى حد كبير.

منذ عام 1978، خضعت قوانين مكافحة الإرهاب في المملكة المتحدة لمراجعة منتظمة من قبل مراجع مستقل في تشريع الإرهاب، والذي غالباً ما يتم تقديم تقاريره المؤثرة إلى البرلمان ونشرها بالكامل.

- تشمل القضايا القانونية الأمريكية المحيطة بهذه المسألة الأحكام المتعلقة بالتوظيف المحلي القوة المميتة من قبل منظمات تنفيذ القانون.

- يخضع التفتيش والمصادرة لـ التعديل الرابع لدستور الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية.

- أصدرت الولايات المتحدة قانون پاتريوت الأمريكي بعد هجمات 11 سبتمبر، بالإضافة إلى مجموعة من التشريعات الأخرى و الأوامر التنفيذية المتعلقة بالأمن القومي.

- تم إنشاء وزارة الأمن الداخلي لتوحيد وكالات الأمن الداخلي لتنسيق مكافحة الإرهاب والاستجابة الوطنية للكوارث الطبيعية الكبرى والحوادث.

- يحد Posse Comitatus Act التوظيف المحلي لـ جيش الولايات المتحدة و القوات الجوية الأمريكية، مما يتطلب موافقة رئاسية قبل نشر الجيش أو القوات الجوية. تطبق سياسة الپنتاگون هذا القيد أيضاً على قوات مشاة البحرية الأمريكية و القوات البحرية الأمريكية، لأن قانون Posse Comitatus لا يغطي الخدمات البحرية، على الرغم من أنها عسكرية فيدرالية القوات. يمكن توظيف وزارة الدفاع محلياً بأمر رئاسي، كما حدث أثناء أعمال الشغب في لوس أنجلس عام 1992، إعصار كاترينا، و قناص بلتواي.

- يتطلب الاستخدام الخارجي أو الدولي للقوة المميتة قرار رئاسي.

- في فبراير 2017، زعمت المصادر أن إدارة ترامب تعتزم إعادة تسمية وتجديد برنامج الحكومة الأمريكية مكافحة التطرف العنيف (CVE) للتركيز فقط على التطرف الإسلامي.[17]

- أقرت أستراليا عدة أعمال لمكافحة الإرهاب. في عام 2004، تم تمرير مشروع قانون يتألف من ثلاثة قوانين قانون مكافحة الإرهاب ، 2004 ، (رقم 2) و (رقم 3). ثم قدم النائب العام فليپ رودك "مشروع قانون مكافحة الإرهاب لعام 2004" في 31 مارس. ووصفه بأنه مشروع قانون لتعزيز قوانين مكافحة الإرهاب الأسترالية في عدد من النواحي – مهمة أصبحت أكثر إلحاحاً في أعقاب المأساوية الأخيرة التفجيرات الإرهابية في إسبانيا. قال إن قوانين مكافحة الإرهاب الأسترالية "تتطلب مراجعة، وعند الضرورة، تحديث إذا أردنا إطار قانوني قادر على حماية جميع الأستراليين من ويلات الإرهاب". يكمل قانون مكافحة الإرهاب الأسترالي لعام 2005 سلطات الأفعال السابقة. يسمح التشريع الأسترالي للشرطة باحتجاز المشتبه بهم لمدة تصل إلى أسبوعين دون تهمة وتعقب المشتبه بهم إلكترونياً لمدة تصل إلى عام. تضمن قانون مكافحة الإرهاب الأسترالي لعام 2005 بند إطلاق النار بهدف القتل. في بلد ذات تقاليد راسخة في الديمقراطية الليبرالية، فإن هذه الإجراءات مثيرة للجدل وقد تعرضت لانتقادات من قبل الجماعات الليبرالية المدنية و الإسلام. [18]

- تراقب إسرائيل قائمة المنظمات الإرهابية المصنفة ولديها قوانين تمنع العضوية في مثل هذه المنظمات وتمويلها أو مساعدتها.

- في 14 ديسمبر 2006، قضت المحكمة الإسرائيلية العليا بأن الاغتيالات هي شكل مسموح به من أشكال الدفاع عن النفس.[19]

- في عام 2016، أصدر الكنيست الإسرائيلي قانوناً شاملاً ضد الإرهاب، يحظر أي نوع من الإرهاب ودعم الإرهاب، ويفرض عقوبات صارمة على الإرهابيين. كما ينظم القانون الجهود القانونية ضد الإرهاب.[20]

Human rights

One of the primary difficulties of implementing effective counter-terrorist measures is the waning of civil liberties and individual privacy that such measures often entail, both for citizens of, and for those detained by states attempting to combat terror.[21] At times, measures designed to tighten security have been seen as abuses of power or even violations of human rights.[22]

Examples of these problems can include prolonged, incommunicado detention without judicial review or long periods of 'preventive detention';[23] risk of subjecting to torture during the transfer, return and extradition of people between or within countries; and the adoption of security measures that restrain the rights or freedoms of citizens and breach principles of non-discrimination.[24] Examples include:

- In November 2003, Malaysia passed new counter-terrorism laws, widely criticized by local human rights groups for being vague and overbroad. Critics claim that the laws put the fundamental rights of free expression, association, and assembly at risk. Malaysia persisted in holding around 100 alleged militants without trial, including five Malaysian students detained for alleged terrorist activity while studying in Karachi, Pakistan.[24]

- In November 2003, a Canadian-Syrian national, Maher Arar, publicly alleged that he had been tortured in a Syrian prison after being handed over to the Syrian authorities by the U.S.[24]

- In December 2003, Colombia's congress approved legislation that would give the military the power to arrest, tap telephones, and carry out searches without warrants or any previous judicial order.[24]

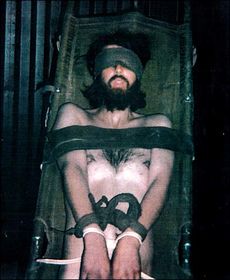

- Images of unpopular treatment of detainees in U.S. custody in Iraq and other locations have encouraged international scrutiny of U.S. operations in the war on terror.[25]

- Hundreds of foreign nationals remain in prolonged indefinite detention without charge or trial in Guantánamo Bay, despite international and U.S. constitutional standards some groups believe outlaw such practices.[25]

- Hundreds of people suspected of connections with the Taliban or al Qa'eda remain in long-term detention in Pakistan or in U.S.-controlled centers in Afghanistan.[25]

- China has used the "war on terror" to justify its policies in the predominantly Muslim Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region to stifle Uighur identity.[25]

- In Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Yemen, and other countries, scores of people have been arrested and arbitrarily detained in connection with suspected terrorist acts or links to opposition armed groups.[25]

- Until 2005 eleven men remained in high security detention in the UK under the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001.[25]

- The United Nations experts condemned the misuse of counter-terrorism powers by the Egyptian authorities following the arrest, detention, and designation of human rights defenders Ramy Shaath and Zyad El-Elaimy under terrorist entities’ list. The two defenders were arrested in June 2019 and the first-ever renewal of remand detention for Shaath came for the 21st time in 19 months on 24 January 2021. Experts claimed it alarming and demanded the urgent implementation of the Working Group’s opinion and removal of the two’s names from the “terrorism entities’ list.[26]

Many would argue that such violations could exacerbate rather than counter the terrorist threat.[24] Human rights advocates argue for the crucial role of human rights protection as an intrinsic part to fight against terrorism.[25][27] This suggests, as proponents of human security have long argued, that respecting human rights may indeed help us to incur security. Amnesty International included a section on confronting terrorism in the recommendations in the Madrid Agenda arising from the Madrid Summit on Democracy and Terrorism (Madrid March 8–11, 2005):

Democratic principles and values are essential tools in the fight against terrorism. Any successful strategy for dealing with terrorism requires terrorists to be isolated. Consequently, the preference must be to treat terrorism as criminal acts to be handled through existing systems of law enforcement and with full respect for human rights and the rule of law. We recommend: (1) taking effective measures to make impunity impossible either for acts of terrorism or for the abuse of human rights in counter-terrorism measures. (2) the incorporation of human rights laws in all anti-terrorism programs and policies of national governments as well as international bodies."[25]

While international efforts to combat terrorism have focused on the need to enhance cooperation between states, proponents of human rights (as well as human security) have suggested that more effort needs to be given to the effective inclusion of human rights protection as a crucial element in that cooperation. They argue that international human rights obligations do not stop at borders, and a failure to respect human rights in one state may undermine its effectiveness in the global effort to cooperate to combat terrorism.[24]

التحييد الوقائي

Some countries see preemptive attacks as a legitimate strategy. This includes capturing, killing, or disabling suspected terrorists before they can mount an attack. Israel, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Russia have taken this approach, while Western European states generally do not.

Another major method of preemptive neutralization is the interrogation of known or suspected terrorists to obtain information about specific plots, targets, the identity of other terrorists, whether or not the interrogation subjects himself is guilty of terrorist involvement. Sometimes more extreme methods are used to increase suggestibility, such as sleep deprivation or drugs. Such methods may lead captives to offer false information in an attempt to stop the treatment, or due to the confusion caused by it. These methods are not tolerated by European powers. In 1978 the European Court of Human Rights ruled in the Ireland v. United Kingdom case that such methods amounted to a practice of inhuman and degrading treatment, and that such practices were in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights Article 3 (art. 3).

غير عسكري

The human security paradigm outlines a non-military approach that aims to address the enduring underlying inequalities which fuel terrorist activity. Causal factors need to be delineated and measures implemented which allow equal access to resources and sustainability for all people. Such activities empower citizens, providing 'freedom from fear' and 'freedom from want'.

This can take many forms, including the provision of clean drinking water, education, vaccination programs, provision of food and shelter and protection from violence, military or otherwise. Successful human security campaigns have been characterized by the participation of a diverse group of actors, including governments, NGOs, and citizens.

Foreign internal defense programs provide outside expert assistance to a threatened government. FID can involve both non-military and military aspects of counter-terrorism.

A 2017 study found that "governance and civil society aid is effective in dampening domestic terrorism, but this effect is only present if the recipient country is not experiencing a civil conflict."[28]

عسكري

Terrorism has often been used to justify military intervention in countries like Pakistan, where terrorists are said to be based. That was the primary stated justification for the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. It was also a stated justification for the second Russian invasion of Chechnya.

Military intervention has not always been successful in stopping or preventing future terrorism, such as during the Malayan Emergency, the Mau Mau uprising, and most of the campaigns against the IRA during the Irish Civil War, the S-Plan, the Border Campaign (IRA) and the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Although military action can temporarily disrupt a terrorist group's operations temporarily, it sometimes does not end the threat completely.[29]

Thus repression by the military in itself (particularly if it is not accompanied by other measures) usually leads to short term victories, but tend to be unsuccessful in the long run (e.g., the French's doctrine described in Roger Trinquier's book Modern War[30] used in Indochina and Algeria). However, new methods (see the new Counterinsurgency Field Manual[31]) such as those taken in Iraq have yet to be seen as beneficial or ineffectual.

Preparation

Police, fire, and emergency medical response organizations have prominent roles. Local firefighters and emergency medical personnel (often called "first responders") have plans for mitigating the effects of terrorist attacks. However, the police may deal with threats of such attacks.

Target-hardening

Whatever the target of terrorists, there are multiple ways of hardening the targets to prevent the terrorists from hitting their mark, or reducing the damage of attacks. One method is to place Hostile vehicle mitigation to enforce protective standoff distance outside tall or politically sensitive buildings to prevent car and truck bombing. Another way to reduce the impact of attacks is to design buildings for rapid evacuation.[32]

Aircraft cockpits are kept locked during flights and have reinforced doors, which only the pilots in the cabin are capable of opening. UK railway stations removed their rubbish bins in response to the Provisional IRA threat, as convenient locations for depositing bombs.

Scottish stations removed theirs after the 7 July 2005 London Bombings as a precautionary measure. The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority purchased bomb-resistant barriers after the September 11 terrorist attacks.

As Israel is suffering from constant shelling of its cities, towns, and settlements by artillery rockets from the Gaza Strip (mainly by Hamas, but also by other Palestinian factions) and Lebanon (mainly by Hezbollah), Israel developed several defensive measures against artillery, rockets, and missiles. These include building a bomb shelter in every building and school, but also deploying active protection systems like the Arrow ABM, Iron Dome and David's Sling batteries which intercept the incoming threat in the air. Iron Dome has successfully intercepted hundreds of Qassam rockets and Grad rockets fired by Palestinians from the Gaza Strip.

A more sophisticated target-hardening approach must consider industrial and other critical industrial infrastructure that could be attacked. Terrorists need not import chemical weapons if they can cause a major industrial accident such as the Bhopal disaster or the Halifax Explosion. Industrial chemicals in manufacturing, shipping, and storage need greater protection, and some efforts are in progress.[33] To put this risk into perspective, the first major lethal chemical attack in WWI used 160 tons of chlorine. Industrial shipments of chlorine, widely used in water purification and the chemical industry, travel in 90- or 55-ton tank cars.

To give one more example, the North American electrical grid has already demonstrated, in the Northeast Blackout of 2003, its vulnerability to natural disasters coupled with inadequate, possibly insecure, SCADA (supervisory control and data acquisition) networks. Part of the vulnerability is due to deregulation, leading to much more interconnection in a grid designed for only occasional power-selling between utilities. A small number of terrorists, attacking critical power facilities when one or more engineers have infiltrated the power control centers, could wreak havoc.

Equipping likely targets with containers (i.e., bags) of pig lard has been utilized to discourage attacks by suicide bombers. The technique was apparently used on a limited scale by British authorities in the 1940s.[34] The approach stems from the idea that Muslims perpetrating the attack would not want to be "soiled" by the lard in the moment before dying. The idea has been suggested more recently as a deterrent to suicide bombings in Israel.[35] However, the actual effectiveness of this tactic is probably limited. A sympathetic Islamic scholar could issue a fatwa proclaiming that a suicide bomber would not be polluted by the swine products.

Command and control

In North America and other continents, for a threatened or completed terrorist attack, the Incident Command System (ICS) is apt to be invoked to control the various services that may need to be involved in the response. ICS has varied levels of escalation, such as might be required for multiple incidents in a given area (e.g., the 2005 bombings in London or the 2004 Madrid train bombings, or all the way to a National Response Plan invocation if national-level resources are needed. For example, a national response might be required for a nuclear, biological, radiological, or significant chemical attack.

تفادي الضرر

Fire departments, perhaps supplemented by public works agencies, utility providers (e.g., gas, water, electricity), and heavy construction contractors, are most apt to deal with the physical consequences of an attack.

الأمن المحلي

Again under an incident command model, local police can isolate the incident area, reducing confusion, and specialized police units can conduct tactical operations against terrorists, often using specialized counter-terrorist tactical units. Bringing in such units will typically involve civil or military authority beyond the local level.

Medical services

Emergency medical services will triage, treat, and transport the more severely affected victims to hospitals, which will need mass casualty and triage plans in place.

Public health agencies, from local to the national level, maybe designated to deal with identification, and sometimes mitigation, of possible biological attacks, and sometimes chemical or radiologic contamination.

الوحدات التكتيكية

Today, many countries have special units designated to handle terrorist threats. Besides various security agencies, there are elite tactical units, also known as special mission units, whose role is to directly engage terrorists and prevent terrorist attacks. Such units perform both in preventive actions, hostage rescue, and responding to ongoing attacks. Countries of all sizes can have highly trained counter-terrorist teams. Tactics, techniques, and procedures for manhunting are under constant development.

Most of these measures deal with terrorist attacks that affect an area or threaten to do so. It is far harder to deal with assassination, or even reprisals on individuals, due to the short (if any) warning time and the quick exfiltration of the assassins.[36]

These units are specially trained in tactics and are very well equipped for CQB with emphasis on stealth and performing the mission with minimal casualties. The units include take-over force (assault teams), snipers, EOD experts, dog handlers, and intelligence officers. See counter-intelligence and counter-terrorism organizations for national command, intelligence, and incident mitigation.

The majority of counter-terrorism operations at the tactical level are conducted by state, federal, and national law enforcement agencies or intelligence agencies. In some countries, the military may be called in as a last resort. Obviously, for countries whose military is legally permitted to conduct police operations, this is a non-issue, and such counter-terrorism operations are conducted by their military.

See counterintelligence for command, intelligence and warning, and incident mitigation aspects of counter-terror.

أمثلة للأفعال

Some counter-terrorist actions of the 20th and 21st centuries are listed below. See list of hostage crises for a more extended list, including hostage-taking that did not end violently.

| Incident | Main locale | Hostage nationality | Kidnappers /hijackers |

Counter-terrorist force | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | Sabena Flight 571 | Tel Aviv-Lod International Airport, Israel | Mixed | Black September | Sayeret Matkal | 1 passenger dead, 2 hijackers killed. 2 passengers and 1 commando injured. 2 kidnappers captured. All other 96 passengers rescued. |

| 1972 | Munich massacre | Munich, West Germany | Israeli | Black September | German police | All hostages murdered, 5 kidnappers killed. 3 kidnappers captured and released. |

| 1975 | AIA building hostage crisis | AIA building, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | Mixed. American and Swedish | Japanese Red Army | Special Actions Unit | All hostages rescued, all kidnappers flown to Libya. |

| 1976 | Operation Entebbe | Entebbe Airport, Uganda | Israelis and Jews. Non-Jewish hostages were released shortly after capture. | PFLP | Sayeret Matkal, Sayeret Tzanhanim, Sayeret Golani | All 6 hijackers, 45 Ugandan troops, 3 hostages, and 1 Israeli soldier dead. 100 hostages rescued |

| 1977 | Lufthansa Flight 181 | Initially over the Mediterranean

Sea, south of the French coast; subsequently Mogadishu International Airport, Somalia |

Mixed | PFLP | GSG 9, Special Air Service consultants | 1 hostage killed before the raid, 3 hijackers dead, 1 captured. 90 hostages rescued. |

| 1980 | Casa Circondariale di Trani Prison riot | Trani, Italy | Italian | Red Brigades | Gruppo di intervento speciale (GIS) | 18 police officers rescued, all terrorists captured. |

| 1980 | Iranian Embassy siege | London, UK | Mostly Iranian but some British | Democratic Revolutionary Movement for the Liberation of Arabistan | Special Air Service | 1 hostage, 5 kidnappers dead, 1 captured. 24 hostages rescued. 1 SAS operative received minor burns. |

| 1981 | Garuda Indonesia Flight 206 | Don Mueang Airport, Bangkok, Thailand | mostly Indonesian, some Europeans/Americans | Jihad Command | Kopassus assault group, RTAF securing perimeter | 5 hijackers killed,1 Kopassus operative killed in action, 1 pilot fatally injured by terrorist, all hostages rescued. |

| 1982 | Kidnapping of General James L. Dozier | Padua, Italy | American | Red Brigades | Nucleo Operativo Centrale di Sicurezza (NOCS) | Hostage saved, capture of the entire terrorist cell. |

| 1983 | Turkish embassy attack | Lisbon, Portugal | Turkish | Armenian Revolutionary Army | GOE | 5 hijackers, 1 hostage and 1 police officer dead, 1 hostage and 1 police officer wounded. |

| 1985 | Achille Lauro hijacking | MS Achille Lauro off the Egyptian coast | Mixed | Palestine Liberation Organization | U.S. military, Italian special forces, Gruppo di intervento speciale turned over to Italy | 1 dead in hijacking, 4 hijackers convicted in Italy |

| 1986 | Pudu Prison siege | Pudu Prison, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | Two doctors | Prisoners | Special Actions Unit | 6 kidnappers captured, 2 hostages rescued |

| 1993 | Indian Airlines Flight 427 | Hijacked between Delhi and Srinagar, India | 141 passengers | Islamic terrorist (Mohammed Yousuf Shah) | National Security Guard | 3 hijackers killed, all hostages rescued |

| 1994 | Air France Flight 8969 | Marseille, France | Mixed | Armed Islamic Group of Algeria | GIGN | 4 hijackers killed, 3 hostages killed before the raid, 229 hostages rescued |

| 1996 | Japanese embassy hostage crisis | Lima, Peru | Japanese and guests (800+) | Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement | Peruvian military & police mixed forces | 1 hostage, 2 rescuers, all 14 kidnappers dead. |

| 1996 | Mapenduma hostage crisis | Mapenduma, Indonesia | Mixed (19 Indonesians, 4 British, 2 Dutch, & 1 German) | Kelly Kwalik's Free Papua Movement (OPM) Group | Kopassus's SAT-81 Gultor CT Group, Kostrad's Infantry Battalion, & Penerbad (Army Aviation) Mixed Forces. | 8 kidnappers dead, 2 kidnappers captured, 2 Hostages killed by kidnappers, 24 Hostages rescued, 5 Army Operatives killed in a helicopter accident. |

| 2000 | Sauk Siege | Perak, Malaysia | Malaysian (2 police officers, 1 soldier and 1 civilian) | Al-Ma'unah | Grup Gerak Khas and 20 Pasukan Gerakan Khas, mixed forces | 2 hostages dead, 2 rescuers dead, 1 kidnapper dead and the other 28 kidnappers captured. |

| 2001-2005 | Pankisi Gorge crisis | Pankisi Gorge, Kakheti, Georgia | Georgians | Mixed, Al-Qaeda and Chechen rebels led by Ibn al-Khattab | 2400 troops and 1000 police officers | Repressing the threats of terrorism in the gorge. |

| 2002 | Moscow theater hostage crisis | Moscow, Russia | Mixed, mostly Russian (900+) | Special Purpose Islamic Regiment | Spetsnaz | 129–204 hostages dead, all 39 kidnappers dead. 600–700 hostages freed. |

| 2004 | Beslan school siege | Beslan, North Ossetia-Alania, Russia | Russian | Riyad-us Saliheen | Mixed Russian | 334 hostages dead and hundreds wounded. 10–21 rescuers dead. 31 kidnappers killed, 1 captured. |

| 2007 | Siege of Lal Masjid | Islamabad, Pakistan | Pakistani students | Students and Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan | Pakistan Army and Rangers, Special Service Group | 61 militants killed, 50 militants captured, 23 students killed, 11 SSG killed, 1 Ranger killed, 33 SSG wounded, 8 soldiers wounded, 3 Rangers wounded, 14 civilians killed |

| 2007 | Kirkuk Hostage Rescue | Kirkuk, Iraq | Turkman child | Islamic State of Iraq Al Qaeda | PUK's Kurdistan Regional Government's Counter Terrorism Group | 5 kidnappers arrested, 1 hostage rescued |

| 2008 | Operation Jaque | Colombia | Mixed | Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia | 15 hostages released. 2 kidnappers captured | |

| 2008 | Operations Dawn | Gulf of Aden, Somalia | Mixed | Somalian piracy and militants | PASKAL and mixed international forces | Negotiation finished. 80 hostages released. RMN, including PASKAL navy commandos with mixed international forces patrolling the Gulf of Aden during this festive period.[37][38][39] |

| 2008 | 2008 Mumbai attacks | Multiple locations in Mumbai city | Indian Nationals, Foreign tourists | Ajmal Qasab and other Pakistani nationals affiliated to Laskar-e-taiba | 300 NSG commandos, 36–100 Marine commandos and 400 army Para Commandos | 141 Indian civilians, 30 foreigners, 15 police officers and two NSG commandos were killed.

9 attackers killed, 1 attacker captured and 293 injured |

| 2009 | 2009 Lahore Attacks | Multiple locations in Lahore city | Pakistan | Lashkar-e-Taiba | Police Commandos, Army Rangers Battalion | March 3, The Sri Lankan cricket team attack – 6 members of the Sri Lankan cricket team were injured, 6 Pakistani police officers and 2 civilians killed.[بحاجة لمصدر]

March 30, the Manawan Police Academy in Lahore attack – 8 gunmen, 8 police personnel and 2 civilians killed, 95 people injured, 4 gunmen captured.[بحاجة لمصدر]. |

| 2011 | Operation Dawn of Gulf of Aden | Gulf of Aden, Somalia | Koreans, Myanmar, Indonesian | Somalian piracy and militants | Republic of Korea Navy Special Warfare Flotilla (UDT/SEAL) | 4+ killed or missing, 8 killed, 5 captured, All hostages rescued. |

| 2012 | Lopota Gorge hostage crisis | Lopota Gorge, Georgia | Georgians | ethnic Chechen, Russian and Georgian militants | Special Operations Center, SOD, KUD and army special forces | 2 KUD members and one special forces corpsman killed, 5 police officers wounded, 11 kidnappers killed, 5 wounded and 1 captured. All hostages rescued. |

| 2013 | 2013 Lahad Datu standoff | Lahad Datu, Sabah, Malaysia | Malaysians | Royal Security Forces of the Sultanate of Sulu and North Borneo (Jamalul Kiram III's faction) | Malaysian Armed Forces, Royal Malaysia Police, Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency and joint counter-terrorism forces as well as Philippine Armed Forces. | 8 police officers including 2 PGK commandos and one soldier killed, 12 others wounded, 56 militants killed, 3 wounded and 149 captured. All hostages rescued. 6 civilians killed and one wounded. |

| 2017 | 2017 Isani flat siege | Isani district, Tbilisi, Georgia | Georgians | Chechen militants | SUS Counter Terror Unit, Police special forces | 3 militants killed, including Akhmed Chatayev. One special forces officer killed during skirmishes. |

Designing anti-terrorism systems

هذا section نبرته أو أسلوبه قد لا تعكس النبرة الموسوعية المستخدمة في موسوعة المعرفة. (June 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The scope for anti-terrorism systems is very large in physical terms (long borders, vast areas, high traffic volumes in busy cities, etc.) as well as in other dimensions, such as type and degree of terrorism threat, political and diplomatic ramifications, and legal issues. In this environment, the development of a persistent anti-terrorism protection system is a daunting task. Such a system should bring together diverse state-of-the-art technologies to enable persistent intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance missions, and enable potential actions. Designing such a system-of-systems comprises a major technological project.

A particular design problem for this system is that it will face many uncertainties in the future. The threat of terrorism may increase, decrease or remain the same, the type of terrorism and location are difficult to predict, and there are technological uncertainties. Yet we want to design a terrorism system conceived and designed today in order to prevent acts of terrorism for a decade or more. A potential solution is to incorporate engineering flexibility into system design for the reason that the flexibility embedded can be exercised in future as uncertainty unfolds and updated information arrives. And the design and valuation of a protection system should not be based on a single scenario, but an array of scenarios. Flexibility can be incorporated in the design of the terrorism system in the form of options that can be exercised in the future when new information is available. Using these 'real options' will create a flexible anti-terrorism system that is able to cope with new requirements that may arise.[40]

Law enforcement/Police

While some countries with longstanding terrorism problems, such as Israel, have law enforcement agencies primarily designed to prevent and respond to terror attacks,[41] in other nations, counter-terrorism is a relatively more recent objective of civilian police and law enforcement agencies.[42][43]

While some civil-libertarians and criminal justice scholars have called-out efforts of law enforcement agencies to combat terrorism as futile and expensive[44] or as threats to civil liberties,[44] other scholars have begun describing and analyzing the most important dimensions of the policing of terrorism as an important dimension of counter-terrorism, especially in the post-9/11 era, and have argued how police institutions view terrorism as a matter of crime control.[42] Such analyses bring out the civilian police role in counter-terrorism next to the military model of a 'war on terror'.[45]

إنفاذ القانون الأمريكي

Pursuant to passage of the Homeland Security Act of 2002, federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies began to systemically reorganize.[46][47] Two primary federal agencies (the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)) house most of the federal agencies that are prepared to combat domestic and international terrorist attacks. These include the Border Patrol, the Secret Service, the Coast Guard and the FBI.

Following suit from federal changes pursuant to 9/11, however, most state and local law enforcement agencies began to include a commitment to "fighting terrorism" in their mission statements.[48][49] Local agencies began to establish more patterned lines of communication with federal agencies. Some scholars have doubted the ability of local police to help in the war on terror and suggest their limited manpower is still best utilized by engaging community and targeting street crimes.[44]

While counter-terror measures (most notably heightened airport security, immigrant profiling[50] and border patrol) have been adapted during the last decade, to enhance counter-terror in law enforcement, there have been remarkable limitations to assessing the actual utility/effectiveness of law enforcement practices that are ostensibly preventative.[51] Thus, while sweeping changes in counter-terrorism rhetoric redefined most American post 9/11 law enforcement agencies in theory, it is hard to assess how well such hyperbole has translated into practice.

In intelligence-led policing(ILP) efforts, the most quantitatively amenable starting point for measuring the effectiveness of any policing strategy (i.e.: Neighborhood Watch, Gun Abatement, Foot Patrols, etc.) is usually to assess total financial costs against clearance rates or arrest rates. Since terrorism is such a rare event phenomena,[52] measuring arrests or clearance rates would be a non-generalizable and ineffective way to test enforcement policy effectiveness. Another methodological problem in assessing counter-terrorism efforts in law enforcement hinges on finding operational measures for key concepts in the study of homeland security. Both terrorism and homeland security are relatively new concepts for criminologists, and academicians have yet to agree on the matter of how to properly define these ideas in a way that is accessible.

وكالات مكافحة الإرهاب

العسكرية

Within military operational approaches Counter-terrorism falls into the category of Irregular Warfare.[53] Given the nature of operational counter-terrorism tasks national military organizations do not generally have dedicated units whose sole responsibility is the prosecution of these tasks. Instead the counter-terrorism function is an element of the role, allowing flexibility in their employment, with operations being undertaken in the domestic or international context.

In some cases the legal framework within which they operate prohibits military units conducting operations in the domestic arena; United States Department of Defense policy, based on the Posse Comitatus Act, forbids domestic counter-terrorism operations by the U.S. military. Units allocated some operational counter-terrorism task are frequently Special Forces or similar assets.

In cases where military organisations do operate in the domestic context some form of formal handover from the law enforcement community is regularly required, to ensure adherence to the legislative framework and limitations. such as the Iranian Embassy Siege, the British police formally turned responsibility over to the Special Air Service when the situation went beyond police capabilities.

انظر أيضاً

- Civilian casualty ratio

- Counterinsurgency

- Counter-IED efforts

- Counterjihad

- Deradicalization

- Explosive detection

- Extrajudicial execution

- Extraordinary rendition

- Fatwa on Terrorism

- Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism

- Informant

- International counter-terrorism operations of Russia

- Irregular warfare

- Manhunt (law enforcement)

- Manhunt (military)

- Preventive State

- Security increase

- Sociology of terrorism

- Special Activities Division, Central Intelligence Agency

- Targeted killing

- Terrorism Research Center

- War amongst the people

الهامش

- ^ Stigall, Miller, and Donnatucci (October 7, 2019). "The 2018 National Strategy for Counterterrorism: A Synoptic Overview". American University National Security Law Brief. SSRN 3466967.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ https://www.doctrine.af.mil/Portals/61/documents/AFDP_3-22/3-22-D01-FID-Introduction.pdf

- ^ "Introduction to Foreign Internal Defense" (PDF). Curtis e. Lemay Center for Doctrine Development and Education. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 24, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ https://sofrep.com/specialoperations/differences-fid-coin-relate-sof/

- ^ https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09592318.2019.1638547

- ^ Aniceto Masferrer, Clive Walker (2013). Counter-Terrorism, Human Rights and the Rule of Law: Crossing Legal Boundaries in Defence of the State. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 294. ISBN 9781781954478.

- ^ Wisnicki, Adrian (2013). Conspiracy, Revolution, and Terrorism from Victorian Fiction to the Modern Novel. Literary Criticism and Cultural Theory. Routledge. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-135-91526-1.

With the collapse of Parnell's political career in 1891 and the general, if temporary, demoralization of the Irish cause, the Special Branch's interests shifted to other revolutionary and anarchist groups, and the word Irish dropped out of the name.

- ^ Tim Newburn, Peter Neyroud (2013). Dictionary of Policing. Routledge. p. 262. ISBN 9781134011551.

- ^ Shaffer, Ryan (2015). "Counter-Terrorism Intelligence, Policy and Theory Since 9/11". Terrorism and Political Violence. 27 (2): 368–375. doi:10.1080/09546553.2015.1006097. S2CID 145270348. Volume 27, Issue 2, 2015.

- ^ "Preventive Counter-Terrorism Measures and Non-Discrimination in the European Union: The Need for Systematic Evaluation". The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism - The Hague (ICCT). 2 July 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ "Which Countries' Terrorist Attacks Are Ignored By The U.S. Media?". FiveThirtyEight. 2016.

- ^ "Trade and Terror: The Impact of Terrorism on Developing Countries". Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 2017.

- ^ Sexton, Renard; Wellhausen, Rachel L.; Findley, Michael G. (2019). "How Government Reactions to Violence Worsen Social Welfare: Evidence from Peru". American Journal of Political Science (in الإنجليزية). 63 (2): 353–367. doi:10.1111/ajps.12415. ISSN 1540-5907.

- ^ https://www.lawfareblog.com/challenges-effective-counterterrorism-intelligence-2020s

- ^ Feiler, Gil (September 2007). "The Globalization of Terror Funding" (PDF). Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, Bar-Ilan University: 29. Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 74. Retrieved November 14, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ https://www.unodc.org/e4j/en/terrorism/module-12/key-issues/surveillance-and-interception.html

- ^ Exclusive: Trump to focus counter-extremism program solely on Islam - sources, Reuters 2017-02-02

- ^ https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/Publications_Archive/archive/TerrorismLaws

- ^ Summary of Israeli Supreme Court Ruling on Targeted Killings Archived فبراير 23, 2013 at the Wayback Machine December 14, 2006

- ^ "Terror bill passes into law". The Jerusalem Post. June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ "Accountability and Transparency in the United States' Counter-Terrorism Strategy". The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism - The Hague (ICCT). 22 January 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Lydia Canaan, The Huffington Post, March 21, 2016

- ^ de Londras, Detention in the War on Terrorism: Can Human Rights Fight Back? (2011)

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Human Rights News (2004): "Human Rights and Counter-Terrorism", in the Briefing to the 60th Session of the UN Commission on Human Rights. online

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Amnesty International (2005): "Counter-terrorism and criminal law in the EU. online

- ^ "UN experts call for removal of rights defenders Ramy Shaath and Zyad El-Elaimy from 'terrorism entities' list". OHCHR. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Preventive Counter-Terrorism Measures and Non-Discrimination in the European Union: The Need for Systematic Evaluation". The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism-The Hague (ICCT). 2 July 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Savun, Burcu; Tirone, Daniel C. (2018). "Foreign Aid as a Counterterrorism Tool - Burcu Savun, Daniel C. Tirone". Journal of Conflict Resolution (in الإنجليزية). 62 (8): 1607–1635. doi:10.1177/0022002717704952. S2CID 158017999.

- ^ Pape, Robert A. (2005). Dying to Win: The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism. Random House. pp. 237–250.

- ^ Trinquier, Roger (1961). "Modern Warfare: A French View of Counterinsurgency". Archived from the original on يناير 12, 2008.

1964 English translation by Daniel Lee with an Introduction by Bernard B. Fall

- ^ Nagl, John A.; Petraeus, David H.; Amos, James F.; Sewall, Sarah (December 2006). "Field Manual 3–24 Counterinsurgency" (PDF). US Department of the Army. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

While military manuals rarely show individual authors, David Petraeus is widely described as establishing many of this volume's concepts.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Ronchi, E. (2015). "Disaster management: Design buildings for rapid evacuation". Nature. 528 (7582): 333. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..333R. doi:10.1038/528333b. PMID 26672544.

- ^ Weiss, Eric M. (January 11, 2005). "D.C. Wants Rail Hazmats Banned: S.C. Wreck Renews Fears for Capital". The Washington Post: B01.

- ^ "Suicide bombing 'pig fat threat". BBC News. February 13, 2004. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Swine: Secret Weapon Against Islamic Terror?". ArutzSheva. December 9, 2007.

- ^ Stathis N. Kalyvas (2004). "The Paradox of Terrorism in Civil Wars" (PDF). Journal of Ethics. 8 (1): 97–138. doi:10.1023/B:JOET.0000012254.69088.41. S2CID 144121872. Archived from the original (PDF) on أكتوبر 11, 2006. Retrieved أكتوبر 1, 2006.

- ^ Crewmen tell of scary ordeal Archived أكتوبر 8, 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Star Sunday October 5, 2008.

- ^ No choice but to pay ransom Archived ديسمبر 5, 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Star Monday September 29, 2008

- ^ "Ops Fajar mission accomplished". The Star. أكتوبر 10, 2008. Archived from the original on October 24, 2008. Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- ^ Buurman, J.; Zhang, S.; Babovic, V. (2009). "Reducing Risk Through Real Options in Systems Design: The Case of Architecting a Maritime Domain Protection System". Risk Analysis. 29 (3): 366–379. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01160.x. PMID 19076327. S2CID 36370133.

- ^ Juergensmeyer, Mark (2000). Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- ^ أ ب Deflem, Mathieu. 2010. The Policing of Terrorism: Organizational and Global Perspectives. New York: Routledge.

- ^ Deflem, Mathieu and Samantha Hauptman. 2013. "Policing International Terrorism." Pp. 64–72 in Globalisation and the Challenge to Criminology, edited by Francis Pakes. London: Routledge. [1]

- ^ أ ب ت Helms, Ronald; Costanza, S E; Johnson, Nicholas (2012-02-01). "Crouching tiger or phantom dragon? Examining the discourse on global cyber-terror". Security Journal (in الإنجليزية). 25 (1): 57–75. doi:10.1057/sj.2011.6. ISSN 1743-4645. S2CID 154538050.

- ^ Michael Bayer. 2010. The Blue Planet: Informal International Police Networks and National Intelligence. Washington, DC: National Intelligence Defense College. [2]

- ^ Costanza, S.E.; Kilburn Jr, John C. (2005). "Symbolic Security, Moral Panic and Public Sentiment: Toward a sociology of Counterterrorism". Journal of Social and Ecological Boundaries. 1 (2): 106–124.

- ^ Deflem, M (2004). "Social Control and the Policing of Terrorism Foundations for a sociology of Counterterrorism". American Sociologist. 35 (2): 75–92. doi:10.1007/bf02692398. S2CID 143868466.

- ^ DeLone, Gregory J. 2007. "Law Enforcement Mission Statements Post September 11." Police Quarterly 10(2)

- ^ Mathieu Deflem. 2010. The Policing of Terrorism: Organizational and Global Perspectives. New York: Routledge.

- ^ Ramirez, D., J. Hoopes, and T.L. Quinlan. 2003 "Defining racial profiling in a post-September 11 world." American Criminal Law Review. 40(3): 1195–1233.

- ^ Kilburn, John C; Jr; Costanza, S.E.; Metchik, Eric; Borgeson, Kevin (2011). "Policing Terror Threats and False Positives: Employing a Signal Detection Model to Examine Changes in National and Local Policing Strategy between 2001–2007". Security Journal. 24: 19–36. doi:10.1057/sj.2009.7. S2CID 153825273.

- ^ Kilburn Jr., John C. and Costanza, S.E. 2009 "Immigration and Homeland Security" published in Battleground: Immigration (Ed: Judith Ann Warner); Greenwood Publishing, Ca.

- ^ Kitzen M. (2020) Operations in Irregular Warfare. In: Sookermany A. (eds) Handbook of Military Sciences. p. 1-21. Springer, Cham DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-02866-4_81-1

للاستزادة

- Ariel Merari, "Terrorism as a Strategy in Insurgency," Terrorism and Political Violence, Vol. 5, No. 4 (Winter 1993), pp. 213–251.

- Edwin Bakker, Tinka Veldhuis, A Fear Management Approach to Counter-Terrorism (International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague, 2012)

- J.M. Berger, Making CVE Work: A Focused Approach Based on Process Disruption, (International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague, May 2016

- Janos Besenyo: Low-cost attacks, unnoticeable plots? Overview on the economical character of current terrorism, Strategic Impact (ROMANIA) (ISSN: 1841–5784) (eISSN: 1824–9904) 62/2017: (Issue No. 1) pp. 83–100.

- Deflem, Mathieu. 2020. "Responses to Terror: Policing and Countering Terrorism in the Modern Age." In The Handbook of Collective Violence: Current Developments and Understanding, eds. C.A. Ireland, et al. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Deflem, Mathieu, and Stephen Chicoine. 2019. "Policing Terrorism." In The Handbook of Social Control, edited by Mathieu Deflem. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Deflem, Mathieu and Shannon McDonough. 2015. "The Fear of Counterterrorism: Surveillance and Civil Liberties Since 9/11." Society 52(1):70-79.

- Gagliano Giuseppe, Agitazione sovversiva, guerra psicologica e terrorismo (2010) ISBN 978-88-6178-600-4, Uniservice Books.

- Ishmael Jones, The Human Factor: Inside the CIA's Dysfunctional Intelligence Culture (2008, revised 2010) ISBN 978-1-59403-382-7, Encounter Books.

- Ivan Arreguín-Toft, "Tunnel at the End of the Light: A Critique of U.S. Counter-terrorist Grand Strategy," Cambridge Review of International Affairs, Vol. 15, No. 3 (2002), pp. 549–563.

- Ivan Arreguín-Toft, "How to Lose a War on Terror: A Comparative Analysis of a Counterinsurgency Success and Failure," in Jan Ångström and Isabelle Duyvesteyn, Eds., Understanding Victory and Defeat in Contemporary War (London: Frank Cass, 2007).

- James Mitchell, "Identifying Potential Terrorist Targets" a study in the use of convergence. G2 Whitepaper on terrorism, copyright 2006, G2. Counterterrorism Conference, June 2006, Washington D.C.

- James F. Pastor, "Terrorism and Public Safety Policing:Implications for the Obama Presidency" (2009, ISBN 978-1-4398-1580-9, Taylor & Francis).

- Jessica Dorsey, Christophe Paulussen, Boundaries of the Battlefield: A Critical Look at the Legal Paradigms and Rules in Countering Terrorism (International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague, 2013)

- Judy Kuriansky (Editor), "Terror in the Holy Land: Inside the Anguish of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict" (2006, ISBN 0-275-99041-9, Praeger Publishers).

- Lynn Zusman (Editor), "The Law of Counterterrorism" (2012, ISBN 978-1-61438-037-5, American Bar Association).* Marc Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), ISBN 0-8122-3808-7.

- Newton Lee, Counterterrorism and Cybersecurity: Total Information Awareness (Second Edition) (Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2015), ISBN 978-3-319-17243-9.

- Teemu Sinkkonen, Political Responses to Terrorism (Acta Universitatis Tamperensis, 2009), ISBN 978-9514478710.

- Vandana Asthana, "Cross-Border Terrorism in India: Counterterrorism Strategies and Challenges," ACDIS Occasional Paper (June 2010), Program in Arms Control, Disarmament, and International Security (ACDIS), University of Illinois

وصلات خارجية

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2013

- Wikipedia articles with style issues from June 2021

- All articles with style issues

- Counter-terrorism

- Law enforcement

- إرهاب

- أمن

- National security

- Public safety