مضادات مستقبلات شبيهات القنب

مضادات مستقبلات شبيهات القنب Cannabinoid receptor antagonist

أدى اكتشاف نظام القنب الداخلى إلى تطوير سي بي 1 مستقبلات مضادات.مستقبلات أول مضادات مستقبلات شبيهات القنب، ريمونابانت وصفت ، في عام 1994 (على الرغم من أنها هي من الناحية التقنية ناهض منعكس ، وليس مضاد).ريمونابانت يغلق إختياريا مستقبلات سي بي11 ولقد ثبت أنه يخفض كمية الغذاء المستهلكة وينظيم عمليةزيادة الوزن بالجسم ، . إن إنتشار السمنة في جميع أنحاء العالم في تزايد كبير و ذلك يؤثر كثيراعلى الصحة العامة. لذا فإن انعدام الكفاءة وكذلك الأدوية ذات الإحتمال الجيد لعلاج السمنة قد أدى إلى زيادة الاهتمام في البحث والتطوير لمضادات مستقبلات شبيهات القنب.[1][2]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ

لقرون الحشيش و الماريجوانا من القنب الهندي كانابيس ستيفا L. قد استخدمت لأغراض طبية وترفيهية.[3][4] في عام 1964 فإن المكون الرئيسي النشطC. ساتيفا L., أ9-تتراهيدروكانابينول (THC), تم فصله وتوليفه من قبل معامل ماكويلامز .[3][5] | وهناك نوعان من مستقبلات القنب ، سى بى1 و سى بى2, المسؤولة عن الآثار التي تم اكتشافها من التتراهيدروكانابينول و مستنسخ في وقت مبكر من 1990.[1][6] وفى الوقت الذى قد اكتشفت فيه مستقبلات القنب, أصبح من الأهمية بمكان تحديد ما إذا كانت مشابهات تحدث طبيعيا في الجسم. هذا البحث أدى إلى اكتشاف الذاتية الأولى من الحشيش (endocannabinoid), anandamide (arachidonoyl ethanolamide). endocannabinoids أخرى في وقت لاحق تم العثور على, فعلى سبيل المثال 2-AG (2-arachidonoyl glycerol).[3] هذه النتائج أثارت المزيد من الأسئلة حول دور الدوائية والفسيولوجية للنظام من الحشيش. أحيت هذه البحوث اللغط على مضادات مستقبلات الحشيش التي كان من المتوقع أن تساعد على إجابة هذه الأسئلة.[6] استخدام محفزات الحشيش ، التتراهيدروكانابينول ، في العديد من الأعمال التحضيرية من أجل تعزيز الشهية هو حقيقة معروفة. هذا الواقع أدى إلى امتداد منطقي وهو أن حظر أو غلق هذه المستقبلات للقنب قد تكون مفيدة في تقليل الشهية للطعام والاستهلاك الغذائي.[7] ثم اكتشف أن انسداد مستقبلات سي بي1 مستقبلات تمثل هدفا جديدا الدوائية1 . أول مستقبل محددCB1 مضادات مستقبلات كان ريمونابانت, وقد أكتشف في عام 1994.[6][7]

شبيهات القنب الداخلية تشير الى النظام

نظام شبيهات القنب الداخلية تتضمن مستقبلات القنب ، وبروابط داخلية (endocannabinoids) والانزيمات للتخليق والتدهور.[8]

هناك نوعان من المستقبلات الرئيسية المرتبطة endocannabinoid تشير الى النظام ؛ مستقبلات القنب 1 (سى بى1) و 2 (سى بى2). كل المستقبلات هي7-transmembrane G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) التي تحول دون تراكم الأدينوساين مونوفوسفات الدوري داخل الخلايا.[9][10] CB1مستقبلات موجودة في أعلى تركيز في الدماغ ولكن يمكن العثور عليها أيضا في المحيط الخارجي. سى بى2المستقبلات التي يقع معظمها في مأمن والأنظمة المنتجة للدم .[1][9]

Endocannabinoids are eicosanoids acting as agonists for cannabinoid receptors and they occur naturally in the body.[5] Cannabinoid receptor-related processes are for example involved in cognition, memory, anxiety, control of appetite, القيىء, التصرف الحركى, sensory, اللاإرادي and neuroendocrine responses, immune responses and inflammatory effects.[8] There are two well-characterized endocannabinoids located in the brain and periphery. The first identified was anandamide (arachidonoyl ethanolamide) and the second was 2-AG (2-arachidonoyl glycerol). Additional endocannabinoids include virodhamine (O-arachidonoyl ethanolamine), noladin ether (2-arachidonoyl glyceryl ether) and NADA (N-arachidonoyl dopamine).[9]

Mechanism of action

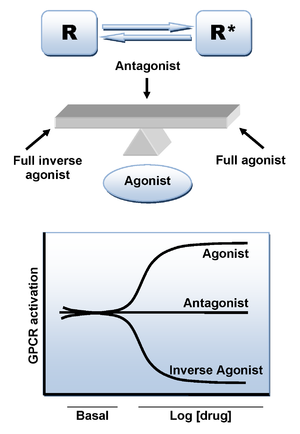

CB1 receptors are coupled through Gi/o proteins and inhibit adenylyl cyclase and activate mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase. In addition, CB1 receptors inhibit presynaptic N- and P/Q-type calcium channels and activate inwardly rectifying potassium channels. [3][7] CB1 antagonists produce inverse cannabimimetic effects that are opposite in direction from those produced by agonists for these receptors.[3][11]

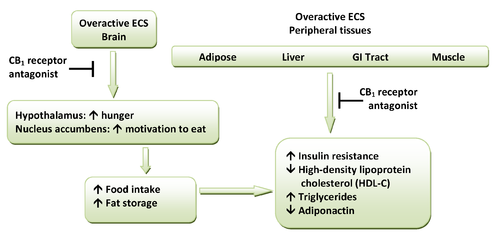

CB1 receptors are highly expressed in hypothalamic areas which are involved in central food intake control and feeding behavior. This strongly indicates that the cannabinoid system is directly involved in feeding regulation. These regions are also interconnected with the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, the so-called "reward" system. Therefore, CB1 antagonists might indirectly inhibit the dopamine-mediated rewarding properties of food.[9][11] Peripheral CB1 receptors are located in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, liver and in adipose tissue. In the GI, CB1 receptors are located on nerve terminals in the intestines. Endocannabinoids act at the CB1 receptors to increase hunger and promote feeding and it is speculated that they decrease intestinal peristalsis and gastric emptying. Thus, antagonism at these receptors can inverse these effects.[9] Also, in peripheral tissues, antagonism of CB1 receptors increases insulin sensitivity and oxidation of fatty acids in muscles and the liver.[1] A hypothetical scheme for the metabolic effects of CB1 receptor antagonists is shown in Figure 1.

Drug design

The first approach to develop cannabinoid antagonists in the late 1980s was to modify the structure of THC but the results were disappointing. In the early 1990s new family of cannabinoid agonists was discovered from the NSAID (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory) drug pravadoline which led to the discovery of aminoalkyl indole antagonists with some but limited success. As the search based on the structure of agonists was disappointing it was no surprise that the first potent and selective cannabinoid antagonist belonged to an entirely new chemical family. In 1994 the first selective cannabinoid antagonist, SR141716 (rimonabant), was introduced by Sanofi belonging to a family of 1,5-diarylpyrazoles.[6][12] ===Rimonabant===

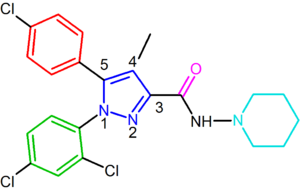

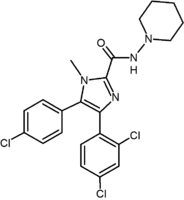

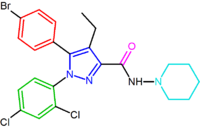

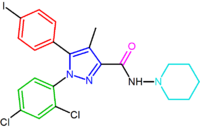

Rimonabant, also known by the systematic name [N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1 H-pyrazole-3-carboxamidehydrochloride)], is a 1,5-diarylpyrazole CB1 receptor antagonist (Figure 2).[12] Rimonabant is not only a potent and highly selective ligand of the CB1 receptor, but it is also orally active and antagonizes most of the effects of cannabinoid agonists, such as THC, both in vitro and in vivo. Rimonabant has shown clear clinical efficacy for the treatment of obesity.[13]

Binding

Diarylpyrazole derivatives

SR141716 (rimonabant) analogs have recently been described by several groups, leading to a good understanding of the structure-activity relationship (SAR) within this chemical group. While most compounds described are less potent than SR141716, two of them are worth mentioning, SR147778 and AM251.[2]

SR147778 (surinabant), a second generation antagonist, has a longer duration of action than rimonabant and enhanced oral activity. This enhanced duration of action is probably due to the presence of the more metabolically stable ethyl group at the 4-position of its pyrazole ring. Another change is the replacement of the 5-phenyl chlorine substituent by bromine.[2][14][15]

The diarylpyrazole derivative, AM251, has been described where chlorine substituent has been replaced by iodine in the para position of the 5-phenyl ring. This derivative appeared to be more potent and selective than rimonabant.[7][13]

21 analogs possessing either an alkyl amide or an alkyl hydrazide of variant lengths in position 3 were synthesized. It was observed that affinity increases with increased carbon chain length up to five carbons. Also the amide analogs exhibited higher affinity than hydrazide analogs. However, none of these analogs possessed significantly greater affinity than rimonabant but nevertheless, they were slightly more selective than rimonabant for the CB1 receptor over the CB2 receptor.[13]

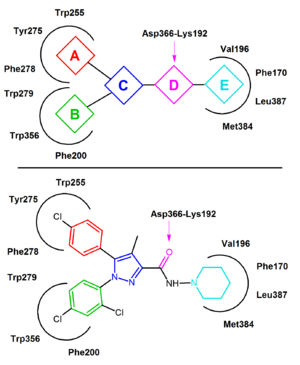

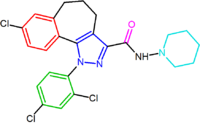

Several attempts have been made to increase the affinity of the diarylpyrazole derivatives by rigidifying the structure of rimonabant. In terms of the general pharmacophore model the units A, B and/or C are connected by additional bonds leading to rigid molecules. For example the condensed polycyclic pyrazole NESS-0327 showed 5000 times more affinity for the CB1 receptor than rimonabant. However, this compound possesses a poor central bioavailability.[14][13]

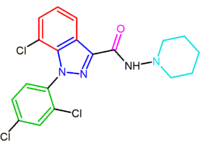

Another compound, the indazole derivative O-1248, can be regarded as an analog of rimonabant wherein its 5-aryl group is fused to the pyrazole moiety. However, this structural modification resulted in a 67-fold decrease in CB1 receptor affinity.[14]

These diarylpyrazole derivatives of rimonabant are summarized in Table 1.

|

|

| SR147778 | AM251 |

|

|

| NESS0327 | O-1248 |

Other derivatives

Structurally different from the 1,5-diarylpyrazoles are the chemical series of the 3,4-diarylpyrazolines. Within this series is SLV-319 (ibipinabant), a potent CB1 antagonist which is about 1000-fold more selective for CB1 compared with CB2 and displays in vivo activity similar to rimonabant.[2][14]

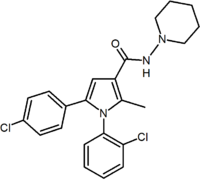

Another approach used to develop analogs of rimonabant was to replace central pyrazole ring by another heterocycle. An example of this approach are 4,5-diarylimidazoles and 1,5-diarylpyrrole-3-carboxamides.[2]

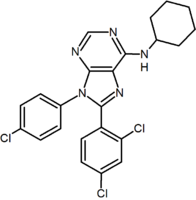

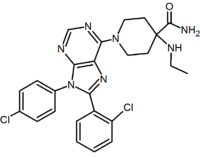

A large number of fused bicyclic derivatives of diaryl-pyrazole and imidazoles have been reported. An example of these is a purine derivative where a pyrimidine ring is fused to an imidazole ring.[2] Otenabant (CP-945,598) is an example of a fused bicyclic derivative developed by Pfizer.[16]

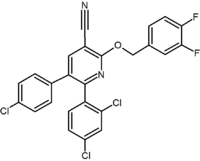

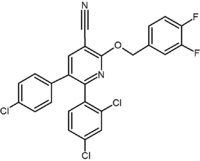

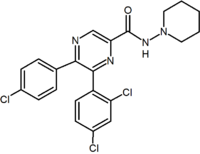

Several research groups have studied six-membered ring pyrazole bioisosteres. For example one 2,3-diarylpyridine derivative was shown to be potent and selective CB1 inverse agonist. The structure of this compound demonstrates the possibility that the amide moiety of rimonabant could be split into a lipophilic (benzyloxy) and a polar (nitrile) functionality. Other six-membered ring analogs are for example pyrimidines and pyrazines.[2]

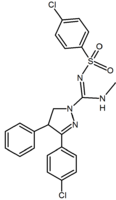

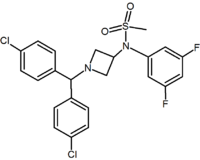

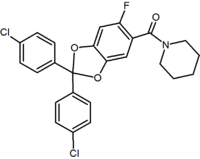

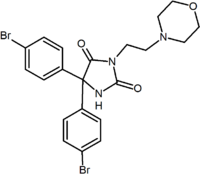

In addition to the five and six-membered ring analogs there are other cyclic derivatives such as the azetidines. One example is the methylsulfonamide azetidine derivative which has a 1,1-diaryl group that mimics the 1,5-diaryl moiety of the diarylpyrazoles. The sulfonyl group serves as a hydrogen bond acceptor. The 1,1-diaryl group is also present in derivatives such as the benzodioxoles and hydantoins.[2][14]

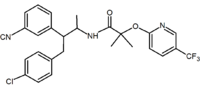

Acyclic analogs have also been reported. These analogs contain a 1,2-diaryl motif which corresponds to the 1,5-diaryl substituents of rimonabant.[2] An example of an acyclic analog is taranabant (MK-0364) developed by Merck.[16]

Representatives of these analogs are summarized in Table 2.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Current status

Rimonabant (Acomplia) has been approved in the European Union (EU) since June 2006 for the treatment of obesity. On 23rd of October 2008 the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) has recommended the suspension of the marketing authorization across the EU for Acomplia from Sanofi-Aventis based on the risk of serious psychiatric disorders.[17] On 5th of November 2008 Sanofi-Aventis announced discontinuation of rimonabant clinical development program.[18]

Sanofi-Aventis has also discontinued development of surinabant (SR147778), a CB1 receptor antagonist for smoking cessation (31st of October 2008).[19]

Merck has stated in its press release on 2nd of October 2008 that they will not seek regulatory approval for taranabant (MK-0364) to treat obesity and will discontinue its Phase III clinical development program. Data from Phase III clinical trial showed that greater efficacy and more adverse effects were associated with the higher doses of taranabant and it was determined that the overall profile of taranabant does not support further development for obesity.[20]

Another pharmaceutical company, Pfizer, terminated the Phase III development program for its obesity compound otenabant (CP-945,598), a selective antagonist of the CB1 receptor. According to Pfizer their decision was based on changing regulatory perspectives on the risk/benefit profile of the CB1 class and likely new regulatory requirements for approval.[21]

انظر أيضاً

References

- ^ أ ب ت ث Patel, P.N.; Pathak, R. (2007), "Rimonabant: A novel selective cannabinoid – 1 receptor antagonist for treatment of obesity", American Journal of Health – System Pharmacy 64: 481 – 489, doi:, PMID 17322160

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Barth, F. (2005), "CB1 Cannabinoid Receptor Antagonists", Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry 40: 103–118, doi:, http://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/bookdescription.cws_home/706482/description#description

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Pertwee, R.G. (2006), "Cannabinoid pharmacology: the first 66 years", British Journal of Pharmacology 147: S163–S171, doi:

- ^ Reggio, P.H. (2003), "Pharmacophores for Ligand Recognition and Activation/Inactivation of the Cannabinoid Receptors", Current Pharmaceutical Design 9: 1607 – 1633, doi:, http://science.kennesaw.edu/projects/cab/CurPharmDes-Reggio-2003.pdf

- ^ أ ب Howlett, A.C.; Breivogel, C.S.; Childers, S.R.; Deadwyler, S.A.; Hampson, R.E.; Porrino, L.J. (2004), "Cannabinoid physiology and pharmacology: 30 years of progress", Neuropharmacology 47: 345 – 358, doi:

- ^ أ ب ت ث Barth, F.; Rinaldi-Carmona, M. (1999), "The Development of Cannabinoid Antagonists", Current Medicinal Chemistry 6: 745–755, http://www.bentham.org/cmc/contabs/vol6-8.html

- ^ أ ب ت ث Mackie, K. (2006), "CANNABINOID RECEPTORS AS THERAPEUTIC TARGETS", Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 46: 101 – 122, doi:, http://www.safeaccessnow.org/downloads/Mackie%20CB%20Receptors%20Annur%20Rev%20Pharm%20Tox%202006.pdf

- ^ أ ب Svíženská, I.; Dubový, P.; Šulcová, A. (2008), "Cannabinoid receptor 1 و 2 ( سى بى1 و سى بى2), their distribution, ligands and functional involvement in nervous system structures – A short review", Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior 90: 501 – 511, doi:

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Xie, S.; Furjanic, M.A.; Ferrara, J.J.; McAndrew, N.R.; Ardino, E.L.; Ngondara, A.; Bernstein, Y.; Thomas, K.J.; et al. (2007), "The endocannabinoid system and rimonabant: a new drug with a novel mechanism of action involving cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonism – or inverse agonism – as potential obesity treatment and other therapeutic use", Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 32: 209 – 231, doi:

- ^ Ashton, J.S.; Wrigth, J.L.; McPartland, J.M.; Tyndall, J.D.A. (2008), "Cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 Receptor Ligand Specificity and the Development of CB2-Selective Agonists", Current Medicinal Chemistry 15: 1428 – 1443, doi:, PMID 18537620

- ^ أ ب Di Marzo, V. (2008), "CB1 receptor antagonism: biological basis for metabolic effects", Drug Discovery Today: 1–16, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=MImg&_imagekey=B6T64-4TP6GKJ-1-F&_cdi=5020&_user=713789&_orig=search&_coverDate=10%2F15%2F2008&_sk=999999999&view=c&wchp=dGLzVzz-zSkzV&md5=6613e4ad928d4bcc2faf43cedabeea60&ie=/sdarticle.pdf

- ^ أ ب Rinaldi – Carmona, M.; Barth, F.; Héaulme, M.; Shire, D.; Calandra, B.; Congy, C.; Martinez, S.; Maruani, J.; et al. (1994), "SR141716A, a potent and selective antagonist of the brain cannabinoid receptor", FEBS Letters 350: 240 – 244, doi:

- ^ أ ب ت ث Muccioli, G.G.; Lambert, D.M. (2005), "Current Knowledge on the Antagonists and Inverse Agonists of Cannabinoid Receptors", Current Medicinal Chemistry 12 (12): 1361–1394, doi:, http://www.farm.ucl.ac.be/Full-texts-FARM/Muccioli-2005-2.pdf

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةLange_2005 - ^ Vemuri, V.K.; Janero, D.R.; Makriyannis, A. (2008), "Pharmacotherapeutic targeting of the endocannabinoid signaling system: Drugs for obesity and the metabolic syndrome", Physiology & Behavior 93: 671 – 686, doi:, PMID 18155257

- ^ أ ب Kim, M.; Yun, H.; Kwak, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, J. (2008), "Design, chemical synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel triazolyl analogues of taranabant (MK-0364), a cannabinoid-1 receptor inverse agonist", Tetrahedron 64: 10802 – 10809, doi:, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=MImg&_imagekey=B6THR-4TJ1HGJ-9-2&_cdi=5289&_user=713789&_orig=search&_coverDate=11%2F24%2F2008&_sk=999359951&view=c&wchp=dGLbVzb-zSkWA&md5=2e8fe6fab24adb1087bd17bbcd3544a7&ie=/sdarticle.pdf

- ^ http://www.emea.europa.eu

- ^ http://en.sanofi-aventis.com

- ^ http://www.sanofi-aventis.ca

- ^ http://www.merck.com

- ^ http://www.pfizer.com