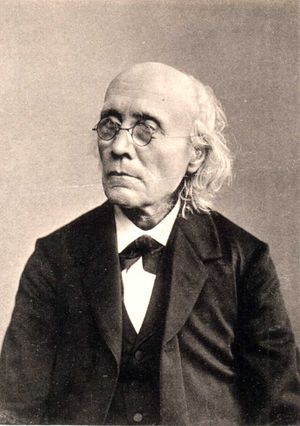

غوستاف فخنر

گوستاف فخنر Gustav Fechner | |

|---|---|

Gustav Fechner | |

| وُلِدَ | أبريل 19, 1801 |

| توفي | نوفمبر 18, 1887 (aged 86) |

| القومية | ألماني |

| التعليم | Medizinische Akademie Carl Gustav Carus Leipzig University (PhD, 1835) |

| عـُرِف بـ | Weber–Fechner law |

| السيرة العلمية | |

| المجالات | علم النفس التجريبي |

| الهيئات | Leipzig University |

| أطروحة | De variis intensitatem vis Galvanicae metiendi methodis [Various methods of measuring Galvanic force intensity] (1835) |

| أبرز الطلاب | Hermann Lotze |

گوستاف تيودور فخنر Gustav Theodor Fechner (عاش 19 أبريل 1801 – 28 نوفمبر 1887) فيلسوف وفيزيائي وعالم نفس ألماني. ولد في بلدة گروس سيرشن Gross-Sérchen بألمانيا، وتوفي في لايپتسيگ. درس الطب في جامعة لايبزيغ، وبعد تخرجه بدأ يهتم بدراسة الفيزياء، والرياضيات، وترجم إلى الألمانية كثيراً من المراجع الفرنسية ذات العلاقة، كما قام بتدريس مادة الفيزياء ثم الفلسفة في جامعة لايبزيج. وهو رائد في علم النفس التجريبي، ومؤسس الفيزياء النفسية (تقنيات لقياس العقل)، وعالم نفس تجريبي. he inspired many 20th-century scientists and philosophers. He is also credited with demonstrating the non-linear relationship between psychological sensation and the physical intensity of a stimulus via the formula: , which became known as the Weber–Fechner law.[1][2]

سيرته

عُرف فخنر أولاً بمذهب فلسفي امتد تأثيره إلى بعض المفكرين الأمريكيين ومنهم وليام جيمس. فقد ذهب في كتابه «زندأفستا أو في أمور السماء وما بعد الموت» Zendavesta oder über die Dinge des Himmels und des Jenseits إلى أن الميتافيزيقيا (علم ما وراء الطبيعة) علم حق يقوم على حاجة فينا للإيمان بمبدأ العدل والخير، وأن الدليل الأقوى على وجود هذا المبدأ هو كوننا نبحث عنه ولا يسعنا إلا أن نبحث عنه. ومنهج الميتافيزيقيا هو تصور العالم على مثال وجداننا فكما أن موضوع العلم الطبيعة المنظورة المعلومة بالملاحظة والاستقراء، فكذلك موضوع الميتافيزيقيا باطن الطبيعة يدرك بالحدس الباطن. هذا الحدس يظهر على أن الوجدان تقدم أفعال من الماضي إلى الحاضر فالمستقبل، وأنه كثرة أفعال في وحدة غير متجزئة، فالعالم من ثمة وحدة حاصلة على الخصائص نفسها، إلا أنه غير محدود. العالم وجدان واحد هو وجدان الله، وكل وجدان - مع تميزه من غيره في الظاهر، فهو مظهر من الوجدان الكلي. والكواكب ملائكة السماء والأرض متنفسة لأنها كل منظم بفصولها المطردة، وأجزاؤها نفوس الموجودات الأرضية من نبات وحيوان وإنسان، وهذه النفوس إضافة إلى الأرض كأفكارنا إضافة إلى أنفسنا.

أعماله

لكن شهرة فخنر تقوم على أنه مؤسس علم النفس الفيزيقي Psychophysik، وهو يعرّف هذا العلم بأنه: «مذهب مضبوط في العلاقات بين النفس والجسم، وعموماً بين العالم الفيزيقي والعالم النفسي» فهو إذن علم تجريبي بحت يتناول الظواهر وقوانينها من دون أن يعرض لجوهر النفس ولا لجوهر الجسم. ولما كانت الفرضية مشروعة في العلم الواقعي، افترض فخنر أن التقابل بين النفس والجسم يرجع إلى أن ما يبدو أنه النفس من الداخل يبدو أنه الجسم من الخارج، وهذا ما سمي «التوازي Parallelism النفسي الفيزيقي» من تأثير متبادل، وقد اتخذ فخنر من قياس الظواهر الخارجية وما تحدثه في الإنسان من ظواهر عصبية قياساً للظواهر النفسية التي لا تقاس مباشرة.

في عام 1850 أعلن فخنر القانون المعروف بقانون فخنر وهو: «إن الزيادة في قوة المنبه Stimulus الضرورية لإحداث أقل زيادة مدركة في الإحساس، تتعلق طرداً بنمو المنبه». وهذا القانون صحيح على وجه التقريب في الإحساسات متوسطة القوة، ولكنه لا يعني أن القياس واقع على الإحساسات بما هي ظواهر وجدانية. فشرع فخنر يجري التجارب، وكان كتابه «عناصر علم النفس الفيزيائي» Elemente der Psychophysik عام 1860 أول كتاب منظَّم في علم النفس مبني على الرياضيات.

ووضع بناء على ذلك جدولين للزيادات: أحدهما للمنبهات والآخر للإحساسات، ولما كانت زيادة المؤثرات مقيسة تبعاً لنسبة مطردة، اعتقد أنه يكفي الافتراض أن كل زيادة مدركة في الإحساس تمثل (وحدة هي هي دائماً)، مما يؤدي إلى سلسلتين متزايدتين يمكن المقارنة بينهما مقارنة رياضية، ووضع هذا القانون: «حين تزداد كثافة المنبه بنسبة هندسية يزداد الإحساس بنسبة حسابية فقط» أو «إن حساب الإحساس ينمو طرداً مع لوغاريتم كثافة المنبه».

وضع فخنر ثلاثة أساليب سيكوفيزيقية مستقلة لقياس العتبات الحسية وهي:

- طريقة التغيرات الصغرى (الحدود)، وفيها قدم عدداً من المنبهات (المثيرات) في سلسلة تتغير صعوداً وهبوطاً.

- طريقة الخطأ المتوسط، وفيها يعدل المفحوص من المنبهات المقدمة إليه وفقاً للتعليمات.

- طريقة حالات الخطأ والصواب، وفيها تقدم إلى المفحوص سلسلة من المنبهات من دون ترتيب.

أثارت أبحاث فخنر اهتماماً بالغاً ومناقشات حادة وحركة واسعة في ميدان علم النفس التجريبي وعلم النفس الفيزيقي والتحليل النفسي. وفي المرحلة الأخيرة من حياته تحول إلى دراسة علم الجمال، وأصدر عديداً من الكتب في هذا المجال ومن أهمها: «المدخل إلى علم الجمال» Vorschule der Ästhetik عام 1876.

إضافة إلى ذلك نـشر فخنر كثيراً من الكتابات الأدبية الساخرة، ولكن دائماً بالاسـم المستعار الدكتور ميزِس Dr.Mises. ومن مؤلفاته المهمة الأخرى: «في مـسألـة الروح» Über die Seelenfrage عـام (1861)، و«الدوافع أو الأسباب الثلاثة للإيمان» Die drei Motive oder Gründe des Glaubens عام (1863)، و«في علم الجمال التجريبي» Zur Experimentalen Ästhetik عام (1873)، و«قضايا علم النفس الفيزيقي»In Sachen der Psychophsik عام (1877).

أثر فخنر اللوني

In 1838, he also studied the still-mysterious perceptual illusion of what is still called the Fechner color effect, whereby colors are seen in a moving pattern of black and white. The English journalist and amateur scientist Charles Benham, in 1894, enabled English-speakers to learn of the effect through the invention of the spinning top that bears his name, Benham's top. Whether Fechner and Benham ever actually met face to face is not known.

الوسط

In his Vorschule der Aesthetik(1876) he used the method of extreme ranks for subjective judgements. Two years later he published a paper which developed the notion of the median and is generally credited with introducing the median into the formal analysis of data.[3] He later explored experimental aesthetics and attempted to determine the shapes and dimensions of aesthetically pleasing objects, using as a database the sizes of paintings.[4]

Synesthesia

In 1871, Fechner reported the first empirical survey of coloured letter photisms among 73 synesthetes.[5][6] His work was followed in the 1880s by that of Francis Galton.[7][8][9]

Corpus callosum split

One of Fechner's speculations about consciousness dealt with brain. During his time, it was known that the brain is bilaterally symmetrical and that there is a deep division between the two halves that are linked by a connecting band of fibers called the corpus callosum. Fechner speculated that if the corpus callosum were split, two separate streams of consciousness would result - the mind would become two. Yet, Fechner believed that his theory would never be tested; he was incorrect. During the mid-twentieth century, Roger Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga worked on epileptic patients with sectioned corpus callosum and observed that Fechner's idea was correct.[10]

فرضية المقطع الذهبي

Fechner constructed ten rectangles with different ratios of width to length and asked numerous observers to choose the "best" and "worst" rectangle shape. He was concerned with the visual appeal of rectangles with different proportions. Participants were explicitly instructed to disregard any associations that they have with the rectangles, e.g. with objects of similar ratios. The rectangles chosen as "best" by the largest number of participants and as "worst" by the fewest participants had a ratio of 0.62 (21:34).[11] This ratio is known as the "golden section" (or golden ratio) and referred to the ratio of a rectangle's width to length that is most appealing to the eye. Carl Stumpf was a participant in this study.

However, there has been some ongoing dispute on the experiment itself, as the fact that Fechner deliberately discarded results of the study ill-fitting to his needs became known, with many mathematicians, including Mario Livio, refuting the result of the experiment.[12]

The two-piece normal distribution

In his posthumously published Kollektivmasslehre (1897), Fechner introduced the Zweiseitige Gauss'sche Gesetz or two-piece normal distribution, to accommodate the asymmetries he had observed in empirical frequency distributions in many fields. The distribution has been independently rediscovered by several authors working in different fields.[13]

مفارقة فخنر

In 1861, Fechner reported that if he looked at a light with a darkened piece of glass over one eye then closed that eye, the light appeared to become brighter, even though less light was coming into his eyes.[14] This phenomenon has come to be called Fechner's paradox.[15] It has been the subject of numerous research papers, including in the 2000s.[16] It occurs because the perceived brightness of the light with both eyes open is similar to the average brightness of each light viewed with one eye.[14]

تأثيره

Fechner, along with Wilhelm Wundt and Hermann von Helmholtz, is recognized as one of the founders of modern experimental psychology. His clearest contribution was the demonstration that because the mind was susceptible to measurement and mathematical treatment, psychology had the potential to become a quantified science. Theorists such as Immanuel Kant had long stated that this was impossible, and that therefore, a science of psychology was also impossible.

Though he had a vast influence on psychophysics, the actual disciples of his general philosophy were few. Ernst Mach was inspired by his work on psychophysics.[17] William James also admired his work: in 1904, he wrote an admiring introduction to the English translation of Fechner's Büchlein vom Leben nach dem Tode (Little Book of Life After Death).

Furthermore, he influenced Sigmund Freud, who refers to Fechner when introducing the concept of psychic locality in his The Interpretation of Dreams that he illustrates with the microscope-metaphor.[18][19][20]

Fechner's world concept was highly animistic. He felt the thrill of life everywhere, in plants, earth, stars, the total universe. Fechner was a panpsychist; he viewed the entire universe as being inwardly alive and consciously animated, instead of being dead “stuff” as accepted by most of his contemporary colleagues, who had become devotees to what was becoming known as material science. Yet he based his panpsychism on a well thought out description of consciousness as waves. He believed that human beings stand midway between the souls of plants and the souls of stars, who are angels.[21] God, the soul of the universe, must be conceived as having an existence analogous to human beings. Natural laws are just the modes of the unfolding of God's perfection. In his last work Fechner, aged but full of hope, contrasts this joyous "daylight view" of the world with the dead, dreary "night view" of materialism. Fechner's work in aesthetics is also important. He conducted experiments to show that certain abstract forms and proportions are naturally pleasing to our senses, and gave some new illustrations of the working of aesthetic association.[22] Charles Hartshorne saw him as a predecessor on his and Alfred North Whitehead's philosophy and regretted that Fechner's philosophical work had been neglected for so long.[23]

Fechner's position in reference to predecessors and contemporaries is not very sharply defined. He was remotely a disciple of Schelling,[22] learned much from Baruch Spinoza, G. W. Leibniz, Johann Friedrich Herbart, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Christian Hermann Weisse, and decidedly rejected G. W. F. Hegel and the monadism of Rudolf Hermann Lotze.

Fechner's work continues to have an influence on modern science, inspiring continued exploration of human perceptual abilities by researchers such as Jan Koenderink, Farley Norman, David Heeger, and others.

التكريم

فوهة فخنر

In 1970, the International Astronomical Union named the Fechner crater on the far side of the Moon after Fechner.[24]

يوم فخنر

In 1985 the International Society for Psychophysics called its annual conference Fechner Day. The conference is now scheduled to include 22 October to allow psychophysicists to celebrate the anniversary of Fechner's waking up on that day in 1850 with a new approach into how to study the mind.[25] Fechner Day runs annually with the 2021 Fechner Day being the 37th.[26] It is organized annually, by a different academic host each year.[27][28][29] During the pandemic resulting from COVID-19, Fechner Day was held online in 2020 and 2021.

العائلة والحياة اللاحقة

Little is known of Fechner's later years, nor of the circumstances, cause, and manner of his death.

Fechner was the brother of painter Eduard Clemens Fechner and of Clementine Wieck Fechner, who was the stepmother of Clara Wieck when Clementine became her father Friedrich Wieck's second wife.[بحاجة لمصدر]

أعماله

مراجع

- ج. ل. فلوجل، علم النفس في مئة عام، ترجمة لطفي فطيم (دار الطليعة، بيروت 1979).

- عبد المنعم الحنفي، موسوعة علم النفس والتحليل النفسي (مكتبة مدبولي، القاهرة 1994).

- يوسف كرم، تاريخ الفلسفة الحديثة (دار المعارف، القاهرة 1966).

Works

- Praemissae ad theoriam organismi generalem (1823).

- (Dr. Mises) Stapelia mixta (1824). Google (Harvard)

- Resultate der bis jetzt unternommenen Pflanzenanalysen (1829). Google (Stanford)

- Maassbestimmungen über die galvanische Kette (1831).

- (Dr. Mises) Schutzmittel für die Cholera (1832). Google (Harvard) — Google (UWisc)

- Repertorium der Experimentalphysik (1832). 3 volumes.

- Volume 1. Google (NYPL) — Google (Oxford)

- Volume 2. Google (NYPL) — Google (Oxford)

- Volume 3. Google (NYPL) — Google (Oxford)

- (ed.) Das Hauslexicon. Vollständiges Handbuch praktischer Lebenskenntnisse für alle Stände (1834-38). 8 volumes.

- Das Büchlein vom Leben nach dem Tode (1836). 6th ed., 1906. Google (Harvard) — Google (NYPL)

- (إنگليزية) On Life After Death (1882). Google (Oxford) — IA (UToronto) 2nd ed., 1906. Google (UMich) 3rd ed., 1914. IA (UIllinois)

- (إنگليزية) The Little Book of Life After Death (1904). IA (UToronto) 1905, Google (UCal) — IA (Ucal) — IA (UToronto)

- (Dr. Mises) Gedichte (1841). Google (Oxford)

- Ueber das höchste Gut (1846). Google (Stanford)

- (Dr. Mises) Nanna oder über das Seelenleben der Pflanzen (1848). 2nd ed., 1899. 3rd ed., 1903. Google (UMich) 4th ed., 1908. Google (Harvard)

- Zend-Avesta oder über die Dinge des Himmels und des Jenseits (1851). 3 volumes. 3rd ed., 1906. Google (Harvard)

- Ueber die physikalische und philosophische Atomenlehre (1855). 2nd ed., 1864. Google (Stanford)

- Professor Schleiden und der Mond (1856). Google (UMich)

- Elemente der Psychophysik (1860). 2 volumes. Volume 1. Google (ULausanne) Volume 2. Google (NYPL)

- Ueber die Seelenfrage (1861). Google (NYPL) — Google (UCal) — Google (UMich) 2nd ed., 1907. Google (Harvard)

- Die drei Motive und Gründe des Glaubens (1863). Google (Harvard) — Google (NYPL)

- Einige Ideen zur Schöpfungs- und Entwickelungsgeschichte der Organismen (1873). Google (UMich)

- (Dr. Mises) Kleine Schriften (1875). Google (UMich)

- Erinnerungen an die letzen Tage der Odlehre und ihres Urhebers (1876). Google (Harvard)

- Vorschule der Aesthetik (1876). 2 Volumes. Google (Harvard)

- In Sachen der Psychophysik (1877). Google (Stanford)

- Die Tagesansicht gegenüber der Nachtansicht (1879). Google (Oxford) 2nd ed., 1904. Google (Stanford)

- Revision der Hauptpuncte der Psychophysik (1882). Google (Harvard)

- Kollektivmasslehre (1897). Google (NYPL)

المصادر

- ^ Fancher, R. E. (1996). Pioneers of Psychology (3rd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-96994-0.

- ^ Sheynin, Oscar (2004), "Fechner as a statistician.", British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology 57 (Pt 1): 53–72, May 2004, doi:, PMID 15171801

- ^ Keynes, John Maynard; A Treatise on Probability (1921), Pt II Ch XVII §5 (p 201).

- ^ Michael Heidelberger. "Gustav Theodor Fechner". /statprob.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ Fechner, G. (1876) Vorschule der Aesthetik. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Hartel. Website: chuoft.pdf

- ^ Campen, Cretien van (1996). De verwarring der zintuigen. Artistieke en psychologische experimenten met synesthesie. Psychologie & Maatschappij, vol. 20, nr. 1, pp. 10–26.

- ^ Galton F (1880). "Visualized Numerals". Nature. 21 (543): 494–5. Bibcode:1880Natur..21..494G. doi:10.1038/021494e0.

- ^ Galton F (1880). "Visualized Numerals". Nature. 21 (533): 252–6. Bibcode:1880Natur..21..252G. doi:10.1038/021252a0.

- ^ Galton F. (1883). Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development. Macmillan. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ^ [Gazzinga, M.S (1970). The bisected brain. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts]

- ^ Fechner, Gustav (1876). Vorschule der Ästhetik. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. pp. 190–202.

- ^ Livio, Mario (2002). The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World's Most Astonishing Number (1st ed.). New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0815-5. OCLC 49226115.

- ^ Wallis, K.F. (2014). "The two-piece normal, binormal, or double Gaussian distribution: its origin and rediscoveries". Statistical Science, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp.106-112. DOI: 10.1214/13-STS417 قالب:ArXiv

- ^ أ ب Levelt, W. J. M. (1965). Binocular brightness averaging and contour information. British Journal of Psychology, 56, 1-13. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1965.tb00939.x

- ^ Robinson, T. R. (1896). Light intensity and depth perception. American Journal of Psychology, 7, 518-532. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1411847

- ^ Ding, J., & Levi, D. M. (2017). Binocular combination of luminance profiles. Journal of Vision, 17(13, 4), 1-32. https://dx.doi.org/10.1167/17.13.4

- ^ Pojman, Paul, "Ernst Mach", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ^ Nicholls, Angus; Liebshcher, Martin (24 June 2010). Thinking the Unconscious: Nineteenth-Century German Thought. Cambridge University Press. p. 272. ISBN 9780521897532.

- ^ Freud, Sigmund (18 March 2015). The Interpretation of Dreams. Translated by A. A. Brill. Mineola New York: Courier Dover Publications. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-486-78942-2.

- ^ Sulloway, Frank J. (1979). Freud: Biologist of the Mind.(pp. 66-67). Basic Books.

- ^ Marshall, M E (1969), "Gustav Fechner, Dr. Mises, and the comparative anatomy of angels.", Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 5 (1): 39–58, Jan 1969, doi:, PMID 11610088

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةEB1911 - ^ For Hartshorne's appreciation of Fechner see his Aquinas to Whitehead – Seven Centuries of Metafysics of Religion. Hartshorne also comments that William James failed to do justice to the theological aspects of Fechner's work. Hartshorne saw also resemblances with the work of Fechner's contemporary Jules Lequier. See also: Hartshorne – Reese (ed.) Philosophers speak of God.

- ^ Fechner, Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature, International Astronomical Union (IAU) Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN)

- ^ Kreuger, L. E. (1993) Personal Communication. ref History of Psychology 4th edition David Hothersal 2004 ISBN 9780072849653

- ^ "Fechner Day 2018 – The International Society for Psychophysics". www.ispsychophysics.org. 21 November 2017.

- ^ "FECHNER DAY 2018". fechnerdays Webseite!. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ "Fechner Day 2017 — Welcome (index)". fechnerday.com. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ "Fechner Day 2023". Fechner Day 2023 - Patrizio Paoletti Foundation. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

قراءات أخرى

- Heidelberger, M. (2001) Gustav Theodor Fechner, Statisticians of the Centuries (ed. C. C. Heyde and E. Seneta) pp. 142-147. New York: Springer.

- Michael Heidelberger. Nature From Within: Gustav Theodor Fechner and his Psychophysical Worldview Trans. Cynthia Klohr. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2004.

- Stephen M Stigler. The History of Statistics: The Measurement of Uncertainty before 1900, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1986. pp. 242-254.

وصلات خارجية

- Works of Gustav Theodor Fechner at Projekt Gutenberg-DE. (German)

- Excerpt from Elements of Psychophysics from the Classics in the History of Psychology website.

- Robert H. Wozniak’s Introduction to Elemente der Psychophysik.

- Biography, bibliography and digitized sources in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using infobox scientist with unknown parameters

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2015

- مواليد 1801

- وفيات 1887

- People from Żary County

- إحصائيون

- علماء نفس

- علماء نفس ألمان

- أشخاص من مقاطعة سيليزيا

- خريجو جامعة لايپتسيگ

- طاقم تدريس جامعة لايپتسيگ

- Academic staff of Leipzig University

- People educated at the Kreuzschule

- 19th-century German mathematicians

- Panpsychism

- Plant cognition

- Quantitative psychologists