شرير

A devil is the personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions.[1] It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force.[2] Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conceptions of the devil can be summed up as 1) a principle of evil independent from God, 2) an aspect of God, 3) a created being turning evil (a fallen angel), and 4) a symbol of human evil.[3]

Each tradition, culture, and religion with a devil in its mythos offers a different lens on manifestations of evil.[4] The history of these perspectives intertwines with theology, mythology, psychiatry, art, and literature developing independently within each of the traditions.[5] It occurs historically in many contexts and cultures, and is given many different names—Satan, Lucifer, Beelzebub, Mephistopheles, Iblis—and attributes: it is portrayed as blue, black, or red; it is portrayed as having horns on its head, and without horns, and so on.[6][7] While depictions of the devil are usually taken seriously, there are times when it is treated less seriously; when, for example, devil figures are used in advertising and on candy wrappers.[4][8]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

أصل الاسم

The Modern English word devil derives from the Middle English devel, from the Old English dēofol, that in turn represents an early Germanic borrowing of the Latin diabolus. This in turn was borrowed from the Greek διάβολος diábolos, "slanderer",[9] from διαβάλλειν diabállein, "to slander" from διά diá, "across, through" and βάλλειν bállein, "to hurl", probably akin to the Sanskrit gurate, "he lifts up".[10]

تعريفات

In his book The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Jeffrey Burton Russell discusses various meanings and difficulties that are encountered when using the term devil. He does not claim to define the word in a general sense, but he describes the limited use that he intends for the word in his book—limited in order to "minimize this difficulty" and "for the sake of clarity". In this book Russell uses the word devil as "the personification of evil found in a variety of cultures", as opposed to the word Satan, which he reserves specifically for the figure in the Abrahamic religions.[11]

In the Introduction to his book Satan: A Biography, Henry Ansgar Kelly discusses various considerations and meanings that he has encountered in using terms such as devil and Satan, etc. While not offering a general definition, he describes that in his book "whenever diabolos is used as the proper name of Satan", he signals it by using "small caps".[12]

The Oxford English Dictionary has a variety of definitions for the meaning of "devil", supported by a range of citations: "Devil" may refer to Satan, the supreme spirit of evil, or one of Satan's emissaries or demons that populate Hell, or to one of the spirits that possess a demonic person; "devil" may refer to one of the "malignant deities" feared and worshiped by "heathen people", a demon, a malignant being of superhuman powers; figuratively "devil" may be applied to a wicked person, or playfully to a rogue or rascal, or in empathy often accompanied by the word "poor" to a person—"poor devil".[13]

البهائية

In the Baháʼí Faith, a malevolent, superhuman entity such as a devil or satan is not believed to exist.[14] These terms do, however, appear in the Baháʼí writings, where they are used as metaphors for the lower nature of man. Human beings are seen to have free will, and are thus able to turn towards God and develop spiritual qualities or turn away from God and become immersed in their self-centered desires. Individuals who follow the temptations of the self and do not develop spiritual virtues are often described in the Baháʼí writings with the word satanic.[14] The Baháʼí writings also state that the devil is a metaphor for the "insistent self" or "lower self" which is a self-serving inclination within each individual. Those who follow their lower nature are also described as followers of "the Evil One".[15][16]

المسيحية

In Christianity, evil is incarnate in the devil or Satan, a fallen angel who is the primary opponent of God.[17][18] Some Christians also considered the Roman and Greek deities as devils.[6][7]

Christianity describes Satan as a fallen angel who terrorizes the world through evil,[17] is the antithesis of truth,[19] and shall be condemned, together with the fallen angels who follow him, to eternal fire at the Last Judgment.[17]

In mainstream Christianity, the devil is usually referred to as Satan. This is because Christian beliefs in Satan are inspired directly by the dominant view of Second Temple Judaism (recorded in the Enochian books), as expressed/practiced by Jesus, and with some minor variations. Some modern Christians[من؟] consider the devil to be an angel who, along with one-third of the angelic host (the demons), rebelled against God and has consequently been condemned to the Lake of Fire. He is described [مطلوب إسناد] as hating all humanity (or more accurately creation), opposing God, spreading lies and wreaking havoc on their souls.

Satan is traditionally identified as the serpent who convinced Eve to eat the forbidden fruit; thus, Satan has often been depicted as a serpent.

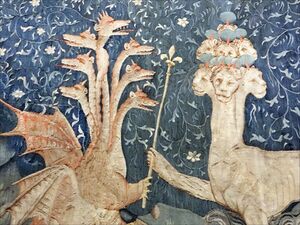

In the Bible, the devil is identified with "the dragon" and "the old serpent" seen in the Book of Revelation,[21] as has "the prince of this world" in the Gospel of John;[22] and "the spirit that now worketh in the children of disobedience" in the Epistle to the Ephesians;[23] and "the god of this world" in 2 Corinthians 4:4.[24] He is also identified as the dragon in the Book of Revelation[25] and the tempter of the Gospels.[26]

The devil is sometimes called Lucifer, particularly when describing him as an angel before his fall.[بحاجة لمصدر] The name "Lucifer" (Latin for "bringer of light", Hebrew hêlēl) is used in the KJV rendering for the "son of the dawn" (ben šāḥar) in Isaiah 14:12, but modern translations use other locutions; the reference is to a Babylonian king.[27]

Beelzebub is originally the name of a Philistine god (more specifically a certain type of Baal, from Ba‘al Zebûb, lit. "Lord of Flies") but is also used in the New Testament as a synonym for the devil. A corrupted version, "Belzeboub", appears in The Divine Comedy (Inferno XXXIV).

In other, non-mainstream, Christian beliefs (e.g. the beliefs of the Christadelphians) the word "satan" in the Bible is not regarded as referring to a supernatural, personal being but to any 'adversary' and figuratively refers to human sin and temptation.[28]

أپوكريفا/القانون الثاني

In the Book of Wisdom, the devil is represented as the one who brought death into the world.[29] The Second Book of Enoch contains references to a Watcher called Satanael,[30] describing him as the prince of the Grigori who was cast out of heaven[31] and an evil spirit who knew the difference between what was "righteous" and "sinful".[32]

In the Book of Jubilees, Satan rules over a host of angels.[33] Mastema, who induced God to test Abraham through the sacrifice of Isaac, is identical with Satan in both name and nature.[34] The Book of Enoch contains references to Sathariel, thought also[ممن؟] to be Sataniel and Satan'el. The similar spellings mirror that of his angelic brethren Michael, Raphael, Uriel, and Gabriel, previous to his expulsion from Heaven.[بحاجة لمصدر]

الديانات الغنوصية

Gnostic and Gnostic-influenced religions postulate the idea that the material world is inherently evil. The One true God is remote, beyond the material universe, therefore this universe must be governed by an inferior imposter deity. This deity was identified with the deity of the Old Testament by some sects, such as the Sethians and the Marcions. Tertullian accuses Marcion of Sinope, that he

[held that] the Old Testament was a scandal to the faithful … and … accounted for it by postulating [that Jehovah was] a secondary deity, a demiurgus, who was god, in a sense, but not the supreme God; he was just, rigidly just, he had his good qualities, but he was not the good god, who was Father of Our Lord Jesus Christ.[35]

John Arendzen (1909) in the Catholic Encyclopedia (1913) mentions that Eusebius accused Apelles, the 2nd-century AD Gnostic, of considering the Inspirer of Old Testament prophecies to be not a god, but an evil angel.[36] These writings commonly refer to the Creator of the material world as "a demiurgus"[35] to distinguish him from the One true God. Some texts, such as the Apocryphon of John and On the Origin of the World, not only demonized the Creator God but also called him by the name of the devil in some Jewish writings, Samael.[37]

كاثار

In the 12th century in Europe the Cathars, who were rooted in Gnosticism, dealt with the problem of evil, and developed ideas of dualism and demonology. The Cathars were seen as a serious potential challenge to the Catholic church of the time. The Cathars split into two camps. The first is absolute dualism, which held that evil was completely separate from the good God, and that God and the devil each had power. The second camp is mitigated dualism, which considers Lucifer to be a son of God, and a brother to Christ. To explain this they used the parable of the prodigal son, with Christ as the good son, and Lucifer as the son that strayed into evilness. The Catholic Church responded to dualism in AD 1215 in the Fourth Lateran Council, saying that God created everything from nothing, and the devil was good when he was created, but he made himself bad by his own free will.[38][39] In the Gospel of the Secret Supper, Lucifer, just as in prior Gnostic systems, appears as a demiurge, who created the material world.[40]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الإسلام

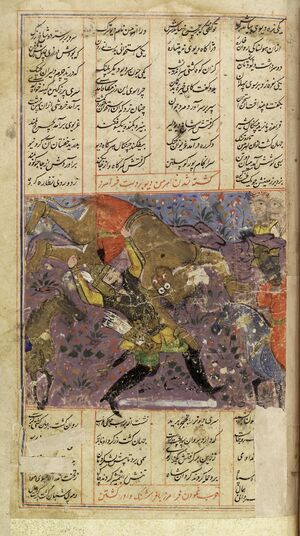

In Islam, the principle of evil is expressed by two terms referring to the same entity:[41][42][43] Shaitan (meaning astray, distant or devil) and Iblis. Iblis is the proper name of the devil representing the characteristics of evil.[44] Iblis is mentioned in the Quranic narrative about the creation of humanity. When God created Adam, he ordered the angels to prostrate themselves before him. All did, but Iblis refused and claimed to be superior to Adam out of pride.قالب:Cite-quran ayah Therefore, pride but also envy became a sign of "unbelief" in Islam.[44] Thereafter Iblis was condemned to Hell, but God granted him a request to lead humanity astray,[45] knowing the righteous would resist Iblis' attempts to misguide them. In Islam, both good and evil are ultimately created by God. But since God's will is good, the evil in the world must be part of God's plan.[46] Actually, God allowed the devil to seduce humanity. Evil and suffering are regarded as a test or a chance to proof confidence in God.[46] Some philosophers and mystics emphasized Iblis himself as a role model of confidence in God, because God ordered the angels to prostrate themselves, Iblis was forced to choose between God's command and God's will (not to praise someone else than God). He successfully passed the test, yet his disobedience caused his punishment and therefore suffering. However, he stays patient and is rewarded in the end.[47]

Muslims hold that the pre-Islamic jinn, tutelary deities, became subject under Islam to the judgment of God, and that those who did not submit to the law of God are devils.[48]

Although Iblis is often compared to the devil in Christian theology, Islam rejects the idea that Satan is an opponent of God and the implied struggle between God and the devil.[مطلوب توضيح] Iblis might either be regarded as the most monotheistic or the greatest sinner, but remains only a creature of God. Iblis did not become an unbeliever due to his disobedience, but because of attributing injustice to God; that is, by asserting that the command to prostrate himself before Adam was inappropriate.[49] There is no sign of angelic revolt in the Quran and no mention of Iblis trying to take God's throne[50][51] and Iblis's sin could be forgiven at anytime by God.[52] According to the Quran, Iblis's disobedience was due to his disdain for humanity, a narrative already occurring in early New Testament apocrypha.[53]

As in Christianity, Iblis was once a pious creature of God but later cast out of Heaven due to his pride. However, to maintain God's absolute sovereignty,[54] Islam matches the line taken by Irenaeus instead of the later Christian consensus that the devil did not rebel against God but against humanity.[55][42] Further, although Iblis is generally regarded as a real bodily entity,[56] he plays a less significant role as the personification of evil than in Christianity. Iblis is merely a tempter, notable for inciting humans into sin by whispering into humans minds (waswās), akin to the Jewish idea of the devil as yetzer hara.[57][58]

On the other hand, Shaitan refers unilaterally to forces of evil, including the devil Iblis, then he causes mischief.[59] Shaitan is also linked to humans psychological nature, appearing in dreams, causing anger or interrupting the mental preparation for prayer.[56] Furthermore, the term Shaitan also refers to beings, who follow the evil suggestions of Iblis. Furthermore, the principle of shaitan is in many ways a symbol of spiritual impurity, representing humans' own deficits, in contrast to a "true Muslim", who is free from anger, lust and other devilish desires.[60]

In Muslim culture, devils are believed to be hermaphrodite creatures created from hell-fire, with one male and one female thigh. By that, they procreate without another mate. It is generally believed that devils can harm the souls of humans through their whisperings. While whisperings tempt humans to sin, the devils might enter the hearth (qalb) of an individual. If the devils take over the soul of a person, this would render them aggressive or insane.[61] In extreme cases, the alterings of the soul are believed to have effect on the body, matching its spiritual qualities.[62]

في الصوفية والباطنية

In contrast to Occidental philosophy, the Sufi idea of seeing "Many as One", and considering the creation in its essence as the Absolute, leads to the idea of the dissolution of any dualism between the ego substance and the "external" substantial objects. The rebellion against God, mentioned in the Quran, takes place on the level of the psyche, that must be trained and disciplined for its union with the spirit that is pure. Since psyche drives the body, flesh is not the obstacle to humans but rather an unawareness that allows the impulsive forces to cause rebellion against God on the level of the psyche. Yet it is not a dualism between body, psyche and spirit, since the spirit embraces both psyche and corporeal aspects of humanity.[63] Since the world is held to be the mirror in which God's attributes are reflected, participation in worldly affairs is not necessarily seen as opposed to God.[57] The devil activates the selfish desires of the psyche, leading the human astray from the Divine.[64] Thus it is the I that is regarded as evil, and both Iblis and Pharao are present as symbols for uttering "I" in ones own behavior. Therefore it is recommended to use the term I as little as possible. It is only God who has the right to say "I", since it is only God who is self-subsistent. Uttering "I" is therefore a way to compare oneself to God, regarded as shirk.[65]

في السلفية

Salafi strands of Islam commonly emphasize a dualistic worldview contrasting believers and unbelievers,[66] and featuring the devil as the enemy of the faithful who tries to lead them astray from God's path. Even though the devil will eventually be defeated by God, he remains a serious and dangerous opponent of humans.[67] While in classical hadiths, the demons (Shayateen) and the jinn are responsible for impurity and capable of endangering human souls, in Salafi thought, it is the devil himself, who lies in wait for believers,[68] always striving to lure them away from God. The devil is regarded as an omnipresent entity, permanently inciting humans into sin, but can be pushed away by remembering the name God.[69] The devil is regarded as an external entity, threatening the everyday life of the believer, even in social aspects of life.[70] Thus for example, it is the devil who is responsible for Western emancipation.[71]

اليهودية

Yahweh, the god in pre-exilic Judaism, created both good and evil, as stated in Isaiah 45:7: "I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil: I the Lord do all these things." The devil does not exist in Jewish scriptures. However, the influence of Zoroastrianism during the Achaemenid Empire introduced evil as a separate principle into the Jewish belief system, which gradually externalized the opposition until the Hebrew term satan developed into a specific type of supernatural entity, changing the monistic view of Judaism into a dualistic one.[72] Later, Rabbinic Judaism rejected[when?] the Enochian books (written during the Second Temple period under Persian influence), which depicted the devil as an independent force of evil besides God.[73] After the apocalyptic period, references to Satan in the Tanakh are thought[ممن؟] to be allegorical.[74]

المندائية

In Mandaean mythology, Ruha fell apart from the World of Light and became the queen of the World of Darkness, also referred to as Sheol.[75][76][77] She is considered evil and a liar, sorcerer and seductress.[78]She gives birth to Ur, also referred to as Leviathan. He is portrayed as a large, ferocious dragon or snake and is considered the king of the World of Darkness.[76] Together they rule the underworld and create the seven planets and twelve zodiac constellations.[76] Also found in the underworld is Krun, the greatest of the five Mandaean Lords of the underworld. He dwells in the lowest depths of creation and his epithet is the 'mountain of flesh'.[79] Prominent infernal beings found in the World of Darkness include lilith, nalai (vampire), niuli (hobgoblin), latabi (devil), gadalta (ghost), satani (Satan) and various other demons and evil spirits.[76][75]

المانوية

In Manichaeism, God and the devil are two unrelated principles. God created good and inhabits the realm of light, while the devil (also called the prince of darkness[80][81]) created evil and inhabits the kingdom of darkness. The contemporary world came into existence, when the kingdom of darkness assaulted the kingdom of light and mingled with the spiritual world.[82] At the end, the devil and his followers will be sealed forever and the kingdom of light and the kingdom of darkness will continue to co-exist eternally, never to commingle again.[83]

Hegemonius (4th century CE) accuses that the Persian prophet Mani, founder of the Manichaean sect in the 3rd century CE, identified Jehovah as "the devil god which created the world"[84] and said that "he who spoke with Moses, the Jews, and the priests … is the [Prince] of Darkness, … not the god of truth."[80][81]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

تنگرية

Among the Tengristic myths of central Asia, Erlik refers to a devil-like figure as the ruler of Tamag (Hell), who was also the first human. According to one narrative, Erlik and God swam together over the primordial waters. When God was about to create the Earth, he sent Erlik to dive into the waters and collect some mud. Erlik hid some inside his mouth to later create his own world. But when God commanded the Earth to expand, Erlik got troubled by the mud in his mouth. God aided Erlik to spit it out. The mud carried by Erlik gave place to the unpleasant areas of the world. Because of his sin, he was assigned to evil. In another variant, the creator-god is identified with Ulgen. Again, Erlik appears to be the first human. He desired to create a human just as Ulgen did, thereupon Ulgen reacted by punishing Erlik, casting him into the Underworld where he becomes its ruler.[85][86]

According to Tengrism, there is no death, meaning that, when life comes to an end, it is merely a transition into the invisible world. As the ruler of Hell, Erlik enslaves the souls, who are damned to Hell. Further, he lurks on the souls of those humans living on Earth by causing death, disease and illnesses. At the time of birth, Erlik sends a Kormos to seize the soul of the newborn, following him for the rest of his life in an attempt to seize his soul by hampering, misguiding, and injuring him. When Erlik succeeds in destroying a human's body, the Kormos sent by Erlik will try take him down into the Underworld. However a good soul will be brought to Paradise by a Yayutshi sent by Ulgen.[87] Some shamans also made sacrifices to Erlik, for gaining a higher rank in the Underworld, if they should be damned to Hell.

اليزيدية

According to Yazidism there is no entity that represents evil in opposition to God; such dualism is rejected by Yazidis,[88] and evil is regarded as nonexistent.[89] Yazidis adhere to strict monism and are prohibited from uttering the word "devil" and from speaking of anything related to Hell.[90]

الزرادشتية

Zoroastrianism probably introduced the first idea of the devil; a principle of evil independently existing apart from God.[91] In Zoroastrianism, good and evil derive from two ultimately opposed forces.[92] The force of good is called Ahura Mazda and the "destructive spirit" in the Avestan language is called Angra Mainyu. The Middle Persian equivalent is Ahriman. They are in eternal struggle and neither is all-powerful, especially Angra Mainyu is limited to space and time: in the end of time, he will be finally defeated. While Ahura Mazda creates what is good, Angra Mainyu is responsible for every evil and suffering in the world, such as toads and scorpions.[91] Iranian Zoroastrians also considered the Daeva as devil creature, because of this in the Shahnameh, it is mentioned as both Ahriman Div (فارسية: اهریمن دیو) as a devil.

الشرير في الفلسفة الأخلاقية

سپينوزا

A non-published manuscript of Spinoza's Ethics contained a chapter (Chapter XXI) on the devil, where Spinoza examined whether the devil may exist or not. He defines the devil as an entity which is contrary to God.[93][94] However, if the devil is the opposite of God, the devil would consist of Nothingness, which does not exist.[93]

In a paper called On Devils, he writes that we can a priori find out that such a thing cannot exist. Because the duration of a thing results in its degree of perfection, and the more essence a thing possess the more lasting it is, and since the devil has no perfection at all, it is impossible for the devil to be an existing thing.[95] Evil or immoral behaviour in humans, such as anger, hate, envy, and all things for which the devil is blamed for could be explained without the proposal of a devil.[93] Thus, the devil does not have any explanatory power and should be dismissed (Occam's razor).

Regarding evil through free-choice, Spinoza asks how it can be that Adam would have chosen sin over his own well-being. Theology traditionally responds to this by asserting it is the devil who tempts humans into sin, but who would have tempted the devil? According to Spinoza, a rational being, such as the devil must have been, could not choose his own damnation.[96] The devil must have known his sin would lead to doom, thus the devil was not knowing, or the devil did not know his sin will lead to doom, thus the devil would not have been a rational being. Spinoza deducts a strict determinism in which moral agency as a free choice, cannot exist.[93]

كانت

In Religion Within the Limits of Reason Alone, Immanuel Kant uses the devil as the personification of maximum moral reprehensibility. Deviating from the common Christian idea, Kant does not locate the morally reprehensible in sensual urges. Since evil has to be intelligible, only when the sensual is consciously placed above the moral obligation can something be regarded as morally evil. Thus, to be evil, the devil must be able to comprehend morality but consciously reject it, and, as a spiritual being (Geistwesen), having no relation to any form of sensual pleasure. It is necessarily required for the devil to be a spiritual being, because if the devil were also a sensual[مطلوب توضيح], it would be possible that the devil does evil to satisfy lower sensual desires, and does not act from the mind alone. The devil acts against morals, not to satisfy a sensual lust, but solely for the sake of evil. As such, the devil is unselfish, for he does not benefit from his evil deeds.

However, Kant denies that a human being could ever be completely devilish. Kant admits that there are devilish vices (ingratitude, envy, and malicious joy), i.e., vices that do not bring any personal advantage, but a person can never be completely a devil. In his Lecture on Moral Philosophy (1774/75) Kant gives an example of a tulip seller who was in possession of a rare tulip, but when he learned that another seller had the same tulip, he bought it from him and then destroyed it instead to keeping it for himself. If he had acted according to his sensual[مطلوب توضيح] in according to his urges, the seller would have kept the tulip for himself to make profit, but not have destroyed it. Nevertheless, the destruction of the tulip cannot be completely absolved from sensual impulses, since a sensual joy or relief still accompanies the destruction of the tulip and therefore cannot be thought of solely as a violation of morality.[97]

Kant further argues that a (spiritual) devil would be a contradiction. If the devil would be defined by doing evil, the devil had no free-choice in the first place. But if the devil had no free-choice, the devil could not have been held accountable for his actions, since he had no free-will but was only following his nature.[98]

الألقاب

Honorifics or styles of address used to indicate devil-figures.

- Ash-Shaytan "Satan", the attributive Arabic term referring to the devil

- Angra Mainyu, Ahriman: "malign spirit", "unholy spirit"

- Dark lord

- Der Leibhaftige [Teufel] (German): "[the devil] in the flesh, corporeal"[99]

- Diabolus, Diabolos (Greek: Διάβολος)

- The Evil One

- The Father of Lies (John 8:44), in contrast to Jesus ("I am the truth").

- Iblis, name of the devil in Islam

- The Lord of the Underworld / Lord of Hell / Lord of this world

- Lucifer / the Morning Star (Greek and Roman): the bringer of light, illuminator; the planet Venus, often portrayed as Satan's name in Christianity

- Kölski (Iceland)[100]

- Mephistopheles

- Old Scratch, the Stranger, Old Nick: a colloquialism for the devil, as indicated by the name of the character in the short story "The Devil and Tom Walker"

- Prince of darkness, the devil in Manichaeism

- Ruprecht (German form of Robert), a common name for the Devil in Germany (see Knecht Ruprecht (Knight Robert))

- Satan / the Adversary, Accuser, Prosecutor; in Christianity, the devil

- (The ancient/old/crooked/coiling) Serpent

- Voland (fictional character in The Master and Margarita)

انظر أيضاً

- Deal with the Devil

- Devil in popular culture

- Hades, Underworld

- Krampus,[101][102] in the Tyrolean area also Tuifl[103][104]

- Non-physical entity

- Theistic Satanism

المراجع

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, pp. 11 and 34

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, p. 34

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1990). Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9718-6.

- ^ أ ب Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, pp. 41–75

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, pp. 44 and 51

- ^ أ ب Arp, Robert. The Devil and Philosophy: The Nature of His Game. Open Court, 2014. ISBN 978-0-8126-9880-0. pp. 30–50

- ^ أ ب Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press. 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3. p. 66.

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey Burton, The Prince of Darkness: Radical Evil and the Power of Good in History, Cornell University Press (1992) ISBN 978-0-8014-8056-0, p. 2

- ^ διάβολος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ "Definition of DEVIL". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell (1987). The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity. Cornell University Press. pp. 11, 34. ISBN 0-8014-9409-5.

- ^ Kelly, Henry Ansgar (2006). Satan: A Biography. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-521-60402-4.

- ^ Craige, W. A.; Onions, C. T. A. "Devil". A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles: Introduction, Supplement, and Bibliography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. (1933) pp. 283–284

- ^ أ ب Smith, Peter (2000). "satan". A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 304. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ^ Bahá'u'lláh; Baháʼuʼlláh (1994) [1873–92]. "Tablet of the World". Tablets of Bahá'u'lláh Revealed After the Kitáb-i-Aqdas. Wilmette, Illinois, US: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 87. ISBN 0-87743-174-4.

- ^ Shoghi Effendi quoted in Hornby, Helen (1983). Hornby, Helen (ed.). Lights of Guidance: A Baháʼí Reference File. Baháʼí Publishing Trust, New Delhi, India. p. 513. ISBN 81-85091-46-3.

- ^ أ ب ت Leeming, David (2005). The Oxford Companion to World Mythology (in الإنجليزية). Oxford University Press (US). ISBN 978-0-19-515669-0.

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, p. 174

- ^ "Definition of DEVIL". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ Fritscher, Jack (2004). Popular Witchcraft: Straight from the Witch's Mouth. Popular Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-299-20304-2.

The pig, goat, ram—all of these creatures are consistently associated with the Devil.

- ^ 12:9, 20:2

- ^ 12:31, 14:30

- ^ 2:2

- ^ 2 Corinthians 2:2

- ^ e.g. Rev. 12:9

- ^ e.g. Matthew 4:1

- ^ See, for example, the entries in Nave's Topical Bible, the Holman Bible Dictionary and the Adam Clarke Commentary.

- ^ "Do you Believe in a Devil? Bible Teaching on Temptation". Archived from the original on 2022-05-29. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- ^ "But by the envy of the devil, death came into the world" – Book of Wisdom II. 24

- ^ 2 Enoch 18:3

- ^ "And I threw him out from the height with his angels, and he was flying in the air continuously above the bottomless" – 2 Enoch 29:4

- ^ "The devil is the evil spirit of the lower places, as a fugitive he made Sotona from the heavens as his name was Satanail, thus he became different from the angels, but his nature did not change his intelligence as far as his understanding of righteous and sinful things" – 2 Enoch 31:4

- ^ Martyrdom of Isaiah, 2:2; Vita Adæ et Evæ, 16)

- ^ Book of Jubilees, xvii. 18

- ^ أ ب

[[wikisource:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/Marcionites "|Marcionites]"]. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

[[wikisource:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/Marcionites "|Marcionites]"]. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^

[[wikisource:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/Gnosticism "|Gnosticism]"]. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

[[wikisource:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/Gnosticism "|Gnosticism]"]. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Birger A. Pearson Gnosticism Judaism Egyptian Fortress Press ISBN 978-1-4514-0434-0 p. 100

- ^ Rouner, Leroy (1983). The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-664-22748-7.

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages, Cornell University Press 1986 ISBN 978-0-801-49429-1, pp. 187–188

- ^ Willis Barnstone, Marvin Meyer The Gnostic Bible: Revised and Expanded Edition Shambhala Publications 2009 ISBN 978-0-834-82414-0 p. 764

- ^ Jane Dammen McAuliffe Encyclopaedia of the Qurʼān Brill 2001 ISBN 978-90-04-14764-5 p. 526

- ^ أ ب Jeffrey Burton Russell, Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages, Cornell University Press 1986 ISBN 978-0-801-49429-1, p. 57

- ^ Benjamin W. McCraw, Robert Arp Philosophical Approaches to the Devil Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-317-39221-7

- ^ أ ب Jerald D. Gort, Henry Jansen, Hendrik M. Vroom Probing the Depths of Evil and Good: Multireligious Views and Case Studies Rodopi 2007 ISBN 978-90-420-2231-7 p. 250

- ^ Quran 17:62

- ^ أ ب Jerald D. Gort, Henry Jansen, Hendrik M. Vroom Probing the Depths of Evil and Good: Multireligious Views and Case Studies Rodopi 2007 ISBN 978-90-420-2231-7 p. 249

- ^ Jerald D. Gort, Henry Jansen, Hendrik M. Vroom Probing the Depths of Evil and Good: Multireligious Views and Case Studies Rodopi 2007 ISBN 978-90-420-2231-7 pp. 254–255

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, p. 58

- ^ Sharpe, Elizabeth Marie Into the realm of smokeless fire: (Qur'an 55:14): A critical translation of al-Damiri's article on the jinn from "Hayat al-Hayawan al-Kubra 1953 The University of Arizona download date: 15/03/2020

- ^ El-Zein, Amira (2009). Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn. Syracuse University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0815650706.

- ^ Vicchio, Stephen J. (2008). Biblical Figures in the Islamic Faith. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock. pp. 175–185. ISBN 978-1556353048.

- ^ Ahmadi, Nader; Ahmadi, Fereshtah (1998). Iranian Islam: The Concept of the Individual. Berlin, Germany: Axel Springer. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-230-37349-5.

- ^ Houtman, Alberdina; Kadari, Tamar; Poorthuis, Marcel; Tohar, Vered (2016). Religious Stories in Transformation: Conflict, Revision and Reception. Leiden, Germany: Brill Publishers. p. 66. ISBN 978-9-004-33481-6.

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 978-0-8156-5070-6 p. 45

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, p. 56

- ^ أ ب Cenap Çakmak Islam: A Worldwide Encyclopedia [4 volumes] ABC-CLIO 2017 ISBN 978-1-610-69217-5 p. 1399

- ^ أ ب Fereshteh Ahmadi, Nader Ahmadi Iranian Islam: The Concept of the Individual Springer 1998 ISBN 978-0-230-37349-5 p. 79

- ^ Nils G. Holm The Human Symbolic Construction of Reality: A Psycho-Phenomenological Study LIT Verlag Münster 2014 ISBN 978-3-643-90526-0 p. 54

- ^ "Shaitan, Islamic Mythology." Encyclopaedia Britannica (Britannica.com). Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Richard Gauvain Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-0-7103-1356-0 p. 74

- ^ Bullard, A. (2022). Spiritual and Mental Health Crisis in Globalizing Senegal: A History of Transcultural Psychiatry. US: Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Woodward, Mark. Java, Indonesia and Islam. Deutschland, Springer Netherlands, 2010. p. 88

- ^ Fereshteh Ahmadi, Nader Ahmadi Iranian Islam: The Concept of the Individual Springer 1998 ISBN 978-0-230-37349-5 p. 81-82

- ^ John O'Kane, Bernd Radtke The Concept of Sainthood in Early Islamic Mysticism: Two Works by Al-Hakim Al-Tirmidhi – An Annotated Translation with Introduction Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-1-136-79309-7 p. 48

- ^ Peter J. Awn Satan's Tragedy and Redemption: Iblis in Sufi Psychology BRILL 1983 ISBN 978-90-04-06906-0 p. 93

- ^ Thorsten Gerald Schneiders Salafismus in Deutschland: Ursprünge und Gefahren einer islamisch-fundamentalistischen Bewegung transcript Verlag 2014 ISBN 978-3-8394-2711-8 p. 392 (German)

- ^ Richard Gauvain Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-0-7103-1356-0 p. 67

- ^ Richard Gauvain Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-0-7103-1356-0 p. 68

- ^ Richard Gauvain Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-0-7103-1356-0 p. 69

- ^ Michael Kiefer, Jörg Hüttermann, Bacem Dziri, Rauf Ceylan, Viktoria Roth, Fabian Srowig, Andreas Zick „Lasset uns in shaʼa Allah ein Plan machen“: Fallgestützte Analyse der Radikalisierung einer WhatsApp-Gruppe Springer-Verlag 2017 ISBN 978-3-658-17950-2 p. 111

- ^ Janusz Biene, Christopher Daase, Julian Junk, Harald Müller Salafismus und Dschihadismus in Deutschland: Ursachen, Dynamiken, Handlungsempfehlungen Campus Verlag 2016 9783593506371 p. 177 (German)

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, p. 58

- ^ Jackson, David R. (2004). Enochic Judaism. London: T&T Clark International. pp. 2–4. ISBN 0-8264-7089-0

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, p. 29

- ^ أ ب Al-Saadi, Qais Mughashghash; Al-Saadi, Hamed Mughashghash (2019). "Glossary". Ginza Rabba: The Great Treasure. An equivalent translation of the Mandaean Holy Book (2 ed.). Drabsha.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Aldihisi, Sabah (2008). The story of creation in the Mandaean holy book in the Ginza Rba (PhD). University College London.

- ^ Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2002). The Mandaeans: ancient texts and modern people. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515385-5. OCLC 65198443.

- ^ Deutsch, Nathniel (2003). Mandaean Literature. In Barnstone, Willis; Meyer, Marvin (2003). The Gnostic Bible. Boston & London: Shambhala.

- ^ Drower, E.S. (1937). The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ أ ب Acta Archelai of Hegemonius, Chapter XII, c. AD 350, quoted in Translated Texts of Manicheism, compiled by Prods Oktor Skjærvø, p. 68.

- ^ أ ب History of the Acta Archelai explained in the Introduction, p. 11

- ^ Willis Barnstone, Marvin Meyer The Gnostic Bible: Revised and Expanded Edition Shambhala Publications 2009 ISBN 978-0-834-82414-0 p. 596

- ^ Willis Barnstone, Marvin Meyer The Gnostic Bible: Revised and Expanded Edition Shambhala Publications 2009 ISBN 978-0-834-82414-0 p. 598

- ^ Manichaeism by Alan G. Hefner in The Mystica, undated

- ^ Mircea Eliade History of Religious Ideas, Volume 3: From Muhammad to the Age of Reforms University of Chicago Press, 31 December 2013 ISBN 978-0-226-14772-7 p. 9

- ^ David Adams Leeming A Dictionary of Creation Myths Oxford University Press 2014 ISBN 978-0-19-510275-8 p. 7

- ^ Plantagenet Publishing The Cambridge Medieval History Series volumes 1–5

- ^ Birgül Açikyildiz The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion I.B. Tauris 2014 ISBN 978-0-857-72061-0 p. 74

- ^ Wadie Jwaideh The Kurdish National Movement: Its Origins and Development Syracuse University Press 2006 ISBN 978-0-815-63093-7 p. 20

- ^ Florin Curta, Andrew Holt Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History [3 volumes] ABC-CLIO 2016 ISBN 978-1-610-69566-4 p. 513

- ^ أ ب Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, p. 99

- ^ John R. Hinnells The Zoroastrian Diaspora: Religion and Migration OUP Oxford 2005 ISBN 978-0-191-51350-3 p. 108

- ^ أ ب ت ث , B. d., Spinoza, B. (1985). The Collected Works of Spinoza, Volume I. Vereinigtes Königreich: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Jarrett, C. (2007). Spinoza: A Guide for the Perplexed. Vereinigtes Königreich: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- ^ Guthrie, S. L. (2018). Gods of this World: A Philosophical Discussion and Defense of Christian Demonology. US: Pickwick Publications.

- ^ Polka, B. (2007). Between Philosophy and Religion, Vol. II: Spinoza, the Bible, and Modernity. Ukraine: Lexington Books.

- ^ Hendrik Klinge: Die moralische Stufenleiter: Kant über Teufel, Menschen, Engel und Gott. Walter de Gruyter, 2018, ISBN 978-3-11-057620-7

- ^ Formosa, Paul. "Kant on the limits of human evil." Journal of Philosophical Research 34 (2009): 189-214.

- ^ Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch s.v. "leibhaftig": "gern in bezug auf den teufel: dasz er kein mensch möchte sein, sondern ein leibhaftiger teufel. volksbuch von dr. Faust […] der auch blosz der leibhaftige heiszt, so in Tirol. Fromm. 6, 445; wenn ich dén sehe, wäre es mir immer, der leibhaftige wäre da und wolle mich nehmen. J. Gotthelf Uli d. pächter (1870) 345

- ^ "Vísindavefurinn: How many words are there in Icelandic for the devil?". Visindavefur.hi.is. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ Krampus: Gezähmter Teufel mit grotesker Männlichkeit, in Der Standard from 5 December 2017

- ^ Wo heut der Teufel los ist, in Kleine Zeitung from 25 November 2017

- ^ Krampusläufe: Tradition trifft Tourismus, in ORF from 4 December 2016

- ^ Ein schiacher Krampen hat immer Saison, in Der Standard from 5 December 2017

وصلات خارجية

The Wiktionary definition of Devil

The Wiktionary definition of Devil Media related to Devils at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Devils at Wikimedia Commons

- Entry from the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Can you sell your soul to the Devil? A Jewish view on the Devil

- CS1 errors: URL

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة from April 2016

- كل مقالات المعرفة التي تحتاج إسناد كلمات أو مقاطع أو مأثورات

- كل مقالات المعرفة التي تحتاج إسناد كلمات أو مقاطع أو مأثورات from April 2016

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from April 2016

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2016

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from June 2021

- Vague or ambiguous time from October 2018

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from October 2018

- Articles containing فارسية-language text

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from January 2023

- Devils

- سفر اليوبيلات

- Fallen angels

- Religious philosophical concepts