شاحن عنفي

شاحن عنفي turbocharger، أو تربو turbo (في اللغة الدارجة)، من اليونانية "τύρβη" ("أثر المخر أي الخضربة")، [1] (وأيضاً من اللاتينية "turbo" ("رأس دوار")،[2]) هو جهاز حث مدفوع forced induction يديره مروحة عنفية turbine يرفع كفاءة وقدرة المحرك بدفع المزيد من الهواء إلى غرفة الاحتراق.[3][4] هذا التحسين على القدرة الناتجة عن محرك مهوى طبيعياً مردّه أن المروحة العنفية يمكنها دفع المزيد من الهواء، وبالتناسب المزيد من الوقود، إلى غرفة الاحتراق، أكثر الضغط الجوي بمفرده.

الشواحن العنفية كانت تُعرف في الأصل بإسم الشواحن الفائقة العنفية turbosuperchargers حين كانت كل أجهزة الحث المدفوع مصنفة كشواحن فائقة. ولكن في هذه الأيام، فإن المصطلح "شاحن فائق supercharger" عادة ما ينحصر استخدامه في الاشارة إلى أجهزة الحث المدفوع المدارة ميكانيكياً.[5] الفرق الرئيسي بين شاحن عنفي وشاحن فائق supercharger اعتيادي هو أن الأخير يدار ميكانيكياً بالمحرك، وكثيراً ما يكون ذلك من خلال سير مربوط بالعمود المرفقي crankshaft، بينما الشاحن العنفي تديره مروحة عنفية يحركها غاز العادم من المحرك. وبالمقارنة بالشاحن الفائق المدار ميكانيكياً، فإن الشواحن العنفية تنحى لأن تكون أكثر كفاءة، ولكن بإستجابة أقل. الشاحن التوأم Twincharger يشير إلى محرك مزود بكلٍ من شاحن فائق وشاحن عنفي.

الشواحن العنفية يشيع استخدامها في محركات الشاحنات والسيارات والقطارات والطائرات ومعدات الإنشاءات. وأكثر استخدامهم يكون مع محركات الاحتراق الداخلي ذات دورة أوتو ودورة ديزل. كما اُكتُشِفت فائدتهم في خلايا الوقود.[6]

التاريخ

الحث المدفوع Forced induction يعود إلى أواخر القرن 19، حين سجل گوتليب دايملر براءة اختراع تقنية استخدام مضخة تديرها تروس لدفع الهواء في محرك احتراق داخلي في 1885.[7]الشاحن العنفي اخترعه المهندس السويسري ألفرد بوشي (1879-1959)، مدير أبحاث محركات الديزل في شركة انتاج المحركات گبرودر سولتسر Gebrüder Sulzer في ڤنترتور،[8] الذي حصل على براءة اختراع في 1905 لاستخدام ضاغط تديره غازات العادم لدفع الهواء في محرك احتراق داخلي لزيادة القدرة الناتجة، إلا أنه مرت عشرون سنة أخرى على الفكرة حتى تثمر.[9][10] وأثناء الحرب العالمية الأولى، ركـّب المهندس الفرنسي أوگوست راتو Auguste Rateau شواحن عنفية في محركات رينو Renault التي كانت تدير مختلف الطائرات المقاتلة الفرنسية، ببعض النجاح.[11] وفي 1918، ألحق مهندس جنرال إلكتريك سانفورد ألكسندر موس Sanford Alexander Moss شاحناً عنفياً بمحرك الطائرات ذي الإثني عشر صماماً ليبرتي Liberty. وقد اُختُبِر المحرك في قمة پايكس Pikes Peak في كولورادو على ارتفاع 14,000 ft (4,300 m) لبيان أن بإمكانه إلغاء فقدان القدرة الذي المشاهـَد في محركات الاحتراق الداخلي نتيجة انخفاض الضغط الجوي والكثافة في الارتفاعات الشاهقة.[11] جنرال إلكتريك سمّت هذا النظام شحن فائق عنفي turbosupercharging.[12] وفي ذلك الوقت، فقد كانت كل أجهزة الحث المدفوع كانت تُعرف بإسم شواحن فائقة superchargers، إلا أنه لاحقاً إصطـُلِح على أن "الشاحن الفائق supercharger" يصِف فقط معدات الحث المدفوع المدارة ميكانيكياً فقط.[5]

Turbochargers were first used in production aircraft engines such as the Napier Lioness[13] in the 1920s, although they were less common than engine-driven centrifugal superchargers. Ships and locomotives equipped with turbocharged Diesel engines began appearing in the 1920s. Turbochargers were also used in aviation, most widely used by the United States. During World War II, notable examples of U.S. aircraft with turbochargers include the B-17 Flying Fortress, B-24 Liberator, P-38 Lightning, and P-47 Thunderbolt. The technology was also used in experimental fittings by a number of other manufacturers, notably a variety of Focke-Wulf Fw 190 models, but the need for advanced high-temperature metals in the turbine kept them out of widespread use.

مبدأ التشغيل

In normally aspirated piston engines, intake gases are "pushed" into the engine by atmospheric pressure filling the volumetric void caused by the downward stroke of the piston[14][15] (which creates a low-pressure area), similar to drawing liquid using a syringe. The amount of air actually inspirated, compared to the theoretical amount if the engine could maintain atmospheric pressure, is called volumetric efficiency.[16] The objective of a turbocharger is to improve an engine's volumetric efficiency by increasing density of the intake gas (usually air).

The turbocharger's compressor draws in ambient air and compresses it before it enters into the intake manifold at increased pressure.[17] This results in a greater mass of air entering the cylinders on each intake stroke. The power needed to spin the centrifugal compressor is derived from the kinetic energy of the engine's exhaust gases.[18]

A turbocharger may also be used to increase fuel efficiency without increasing power.[19] This is achieved by recovering waste energy in the exhaust and feeding it back into the engine intake. By using this otherwise wasted energy to increase the mass of air, it becomes easier to ensure that all fuel is burned before being vented at the start of the exhaust stage. The increased temperature from the higher pressure gives a higher Carnot efficiency.

The control of turbochargers is very complexقالب:Elucidate and has changed dramatically over the 100-plus years of its use. Modern turbochargers can use wastegates, blow-off valves and variable geometry, as discussed in later sections.

The reduced density of intake air is often compounded by the loss of atmospheric density seen with elevated altitudes. Thus, a natural use of the turbocharger is with aircraft engines. As an aircraft climbs to higher altitudes, the pressure of the surrounding air quickly falls off. At 5,486 metres (17,999 ft), the air is at half the pressure of sea level, which means that the engine produces less than half-power at this altitude.[20]

زيادة الضغط (أو الرفع)

In automotive applications, boost refers to the amount by which intake manifold pressure exceeds atmospheric pressure. This is representative of the extra air pressure that is achieved over what would be achieved without the forced induction. The level of boost may be shown on a pressure gauge, usually in bar, psi or possibly kPa.[20]

In aircraft engines, turbocharging is commonly used to maintain manifold pressure as altitude increases (i.e. to compensate for lower-density air at higher altitudes). Since atmospheric pressure reduces as the aircraft climbs, power drops as a function of altitude in normally aspirated engines. Systems that use a turbocharger to maintain an engine's sea-level power output are called turbo-normalized systems. Generally, a turbo-normalized system attempts to maintain a manifold pressure of 29.5 inches of mercury (100 kPa).[20]

In all turbocharger applications, boost pressure is limited to keep the entire engine system, including the turbocharger, inside its thermal and mechanical design operating range. Over boosting an engine frequently causes damage to the engine in a variety of ways including pre-ignition, overheating, and over-stressing the engine's internal hardware.

For example, to avoid engine knocking (a.k.a. detonation) and the related physical damage to the engine, the intake manifold pressure must not get too high, thus the pressure at the intake manifold of the engine must be controlled by some means. Opening the wastegate allows the excess energy destined for the turbine to bypass it and pass directly to the exhaust pipe, thus reducing boost pressure. The wastegate can be either controlled manually (frequently seen in aircraft) or by an actuator (in automotive applications, it is often controlled by the engine control unit).

Turbocharger lag

Turbocharger lag (turbo lag) is the time required to change power output in response to a throttle change, noticed as a hesitation or slowed throttle response when accelerating as compared to a naturally aspirated engine. This is due to the time needed for the exhaust system and turbocharger to generate the required boost. Inertia, friction, and compressor load are the primary contributors to turbocharger lag. Superchargers do not suffer this problem, because the turbine is eliminated due to the compressor being directly powered by the engine.

Turbocharger applications can be categorized into those that require changes in output power (such as automotive) and those that do not (such as marine, aircraft, commercial automotive, industrial, engine-generators, and locomotives). While important to varying degrees, turbocharger lag is most problematic in applications that require rapid changes in power output. Engine designs reduce lag in a number of ways:

- Lowering the rotational inertia of the turbocharger by using lower radius parts and ceramic and other lighter materials

- Changing the turbine's aspect ratio

- Increasing upper-deck air pressure (compressor discharge) and improving wastegate response

- Reducing bearing frictional losses, e.g., using a foil bearing rather than a conventional oil bearing

- Using variable-nozzle or twin-scroll turbochargers

- Decreasing the volume of the upper-deck piping

- Using multiple turbochargers sequentially or in parallel

- Using an antilag system

- Using a turbocharger spool valve to increase exhaust gas flow speed to the (twin-scroll) turbine

عتبة الرفع

The boost threshold of a turbocharger system is the lower bound of the region within which the compressor operates. Below a certain rate of flow, a compressor produces insignificant boost. This limits boost at a particular RPM, regardless of exhaust gas pressure. Newer turbocharger and engine developments have steadily reduced boost thresholds.

Electrical boosting ("E-boosting") is a new technology under development. It uses an electric motor to bring the turbocharger up to operating speed quicker than possible using available exhaust gases.[21] An alternative to e-boosting is to completely separate the turbine and compressor into a turbine-generator and electric-compressor as in the hybrid turbocharger. This makes compressor speed independent of turbine speed. In 1981, a similar system that used a hydraulic drive system and overspeed clutch arrangement accelerated the turbocharger of the MV Canadian Pioneer (Doxford 76J4CR engine).[بحاجة لمصدر]

Turbochargers start producing boost only when a certain amount of kinetic energy is present in the exhaust gasses. Without adequate exhaust gas flow to spin the turbine blades, the turbocharger cannot produce the necessary force needed to compress the air going into the engine. The boost threshold is determined by the engine displacement, engine rpm, throttle opening, and the size of the turbocharger. The operating speed (rpm) at which there is enough exhaust gas momentum to compress the air going into the engine is called the "boost threshold rpm". Reducing the "boost threshold rpm" can improve throttle response.

المكونات الرئيسية

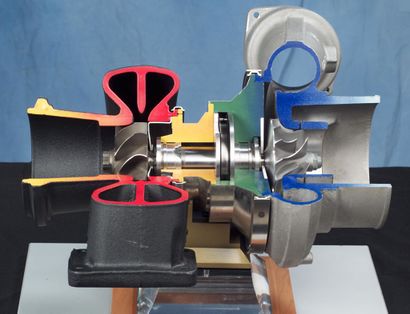

يتكون الشاحن العنفي من ثلاث مكونات رئيسية:

- التوربين، الذي يكاد يكون دوماً توربين للإدخال القطري (ولكنه يكاد يكون دوماً توربين إدخال محوري أحادي المرحلة في محركات الديزل الكبيرة)

- The compressor, which is almost always a centrifugal compressor

- The center housing/hub rotating assembly

توربين Turbine

العنفات التوأم Twin-turbo

Twin-scroll

Twin-scroll or divided turbochargers have two exhaust gas inlets and two nozzles, a smaller sharper angled one for quick response and a larger less angled one for peak performance.

الشكل المتغير

Garrett variable-geometry turbocharger on DV6TED4 engine |

الضاغط

The compressor increases the mass of intake air entering the combustion chamber. The compressor is made up of an impeller, a diffuser and a volute housing.

The operating range of a compressor is described by the "compressor map".

Ported shroud

Center housing/hub rotating assembly

Ball bearings designed to support high speeds and temperatures are sometimes used instead of fluid bearings to support the turbine shaft. This helps the turbocharger accelerate more quickly and reduces turbo lag.[22] Some variable nozzle turbochargers use a rotary electric actuator, which uses a direct stepper motor to open and close the vanes, rather than pneumatic controllers that operate based on air pressure.[23]

تقنيات اضافية يشيع استخدامها في تركيبات الشاحن العنفي

التبريد الداخلي Intercooling

حقن الماء

An alternative to intercooling is injecting water into the intake air to reduce the temperature. This method has been used in automotive and aircraft applications.

نسبة خلط الوقود-الهواء

Wastegate

صمامات Anti-surge/dump/blow off

تعويم حر

الاستخدامات

السيارات التي تدور بالبنزين

The first turbocharged passenger car was the Oldsmobile Jetfire option on the 1962-1963 F85/Cutlass, which used a turbocharger mounted to a 215 cu in (3.52 L) all aluminum V8. Also in 1962, Chevrolet introduced a special run of turbocharged Corvairs, initially called the Monza Spyder (1962-1964) and later renamed the Corsa (1965-1966), which mounted a turbocharger to its air cooled flat six cylinder engine. This model popularized the turbocharger in North America—and set the stage for later turbocharged models from Porsche on the 1975-up 911/930, Saab on the 1978-1984 Saab 99 Turbo, and the very popular 1978-1987 Buick Regal/T Type/Grand National. Today, turbocharging is common on both Diesel and gasoline-powered cars. Turbocharging can increase power output for a given capacity[24] or increase fuel efficiency by allowing a smaller displacement engine. The 'Engine of the year 2011' is an engine used in a Fiat 500 equipped with an MHI turbocharger. This engine lost 10% weight, saving up to 30% in fuel consumption while delivering the same HP (105) as an 1.4 litre engine. The 2013 Chevrolet Cruze is available with either a 1.8 litre non-turbocharged engine or a 1.4 litre turbocharged engine—both produce the same 138 horsepower. Low pressure turbocharging is the optimum when driving in the city, whereas high pressure turbocharging is more for racing and driving on highways/motorways/freeways.

السيارات التي تدور بالديزل

The first production turbocharger Diesel passenger car was the Garrett-turbocharged[25] Mercedes 300SD introduced in 1978.[26][27] Today, many automotive Diesels are turbocharged, since the use of turbocharging improved efficiency, driveability and performance of Diesel engines,[26][27] greatly increasing their popularity. The Audi R10 with a Diesel engine even won the 24 hours race of Le Mans in 2006, 2007 and 2008.

الدراجات النارية

The first example of a turbocharged bike is the 1978 Kawasaki Z1R TC.[28] Several Japanese companies produced turbocharged high performance motorcycles in the early 1980s, such as the CX500 Turbo from Honda- a transversely mounted, liquid cooled V-Twin also available in naturally aspirated form. Since then, few turbocharged motorcycles have been produced. This is partially due to an abundance of larger displacement, naturally aspirated engines being available that offer the torque and power benefits of a smaller displacement engine with turbocharger, but do return more linear power characteristics. The Dutch manufacturer EVA motorcycles builds a small series of turbocharged Diesel motorcycle with an 800cc smart CDI engine.

الشاحنات

The first turbocharged Diesel truck was produced by Schweizer Maschinenfabrik Saurer (Swiss Machine Works Saurer) in 1938.[29]

الطائرات

A natural use of the turbocharger — and its earliest known use for any internal combustion engine, starting with experimental installations in the 1920s — is with aircraft engines. As an aircraft climbs to higher altitudes the pressure of the surrounding air quickly falls off. At 5,486 m (18,000 ft), the air is at half the pressure of sea level and the airframe experiences only half the aerodynamic drag. However, since the charge in the cylinders is pushed in by this air pressure, the engine normally produces only half-power at full throttle at this altitude. Pilots would like to take advantage of the low drag at high altitudes to go faster, but a naturally aspirated engine does not produce enough power at the same altitude to do so.

The table below is used to demonstrate the wide range of conditions experienced. As seen in the table below, there is significant scope for forced induction to compensate for lower density environments.

Daytona Beach Denver Death Valley Colorado State Highway 5 La Rinconada, Peru, elevation 0 m / 0 ft 1,609 m / 5,280 ft -86 m / -282 ft 4,347 m / 14,264 ft 5,100 m / 16,732 ft atm 1.000 0.823 1.010 0.581 0.526 bar 1.013 0.834 1.024 0.589 0.533 psia 14.696 12.100 14.846 8.543 7.731 kPa 101.3 83.40 102.4 58.90 53.30

Marine and land-based Diesel turbochargers

Turbocharging, which is common on Diesel engines in automobiles, trucks, tractors, and boats is also common in heavy machinery such as locomotives, ships, and auxiliary power generation.

السلامة

Turbocharger failures and resultant high exhaust temperatures are among the recognized causes of car fires.[30]

انظر أيضاً

- Boost gauge

- Twincharger

- Exhaust pulse pressure charging

- Hybrid turbocharger

- Twin-turbo

- Variable geometry turbocharger

الهامش

- ^ "τύρβη - Λεξιλόγιο - Γεώργιος Μπαμπινιώτης". Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ "Turbo - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ Nice, Karim (4 December 2000). "How Turbochargers Work". Auto.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ أ ب "supercharger - Wiktionary". En.wiktionary.org. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Baines, Nicholas C. (2005). Fundamentals of Turbocharging. Concepts ETI. ISBN 0-933283-14-8.

- ^ "History of the Supercharger". Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ Porsche Turbo: The Full History. Peter Vann. MotorBooks International, 11 July 2004

- ^ Compressor Performance: Aerodynamics for the User. M. Theodore Gresh. Newnes, 29 March 2001

- ^ Diesel and gas turbine progress, Volume 26. Diesel Engines, 1960

- ^ أ ب "Hill Climb". Air & Space Magazine. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ^ "The Turbosupercharger and the Airplane Powerplant".

- ^ "Gallery". Picturegallery.imeche.org. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ "Four Stroke Engine Basics". Compgoparts.com. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Brain, Marshall (5 April 2000). "HowStuffWorks "Internal Combustion"". Howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ "Volumetric Efficiency (and the REAL factor: mass airflow)". Epi-eng.com. 18 November 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ "Variable-Geometry Turbochargers". Large.stanford.edu. 24 October 2010. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ "How Turbo Chargers Work". Conceptengine.tripod.com. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ "Effects of Variable Geometry Turbochargers in Increasing Efficiency and Reducing Lag - Thermal Systems". Me1065.wikidot.com. 6 December 2007. doi:10.1243/0954407991526766. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ أ ب ت Knuteson, Randy (July 1999). "Boosting Your Knowledge of Turbocharging" (PDF). Aircraft Maintenance Technology. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ Parkhurst, Terry. "Turbochargers: an interview with Garrett's Martin Verschoor". Allpar. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- ^ Nice, Karim. "How Turbochargers Work". Auto.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ^ Hartman, Jeff (15 November 2007). "Turbocharging Performance Handbook". MotorBooks International. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ Richard Whitehead (25 May 2010). "Road Test: 2011 Mercedes-Benz CL63 AMG". Thenational.ae. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ "Turbocharging Turns 100". Honeywell. 2005. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ أ ب "The history of turbocharging". En.turbolader.net. 27 October 1959. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ أ ب http://www.theturboforums.com/turbotech/main.htm

- ^ Smith, Robert (January–February 2013). "1978 Kawasaki Z1R-TC: Turbo Power". Motorcycle Classics. 8 (3). Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ "BorgWarner turbo history". Turbodriven.com. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ^ Why Trucks Catch Fire. Australian Road Transport Suppliers Association. November 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

وصلات خارجية

- Don Sherman (February 2006). "Happy 100th Birthday to the Turbocharger". Automobile Magazine.

- NASA Oil Free Turbocharger

- Video showing how a turbocharger works