سد هوڤر

| سـد هـوڤـر Hoover Dam | |

|---|---|

| |

| الحالة | In use |

| تكلفة الإنشاء | $49 مليون |

| المالك | حكومة الولايات المتحدة |

| السد والمفايض | |

| نوع المفيض | 2 x controlled drum-gate |

| سعة المفيض | 400،000 cu ft/s (11،000 m3/s) |

| محطة الطاقة | |

| المشغل | U.S. Bureau of Reclamation |

| الموقع الإلكتروني Bureau of Reclamation: Lower Colorado Region – سد هوڤر | |

Hoover Dam | |

| |

| أقرب مدينة | بولدر سيتي، نـِڤادا |

| الإحداثيات | 36°0′56″N 114°44′16″W / 36.01556°N 114.73778°W |

| بُنيَ | 1933 |

| المعماري | سيكس كمپانيز (الإنشائي)، Gordon Kaufmann (الواجهات) |

| الطراز المعماري | Art Deco |

| MPS | Vehicular Bridges in Arizona MPS (AD) |

| رقم NRHP المرجعي | خطأ لوا: invalid capture index %2 in replacement string. |

| تواريخ بارزة | |

| أضيف إلى NRHP | April 08, 1981[1] |

| Designated NHL | August 20, 1985[2] |

خطأ في التعبير: عامل < غير متوقع.

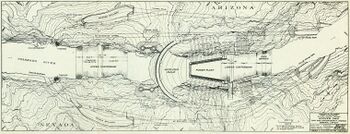

سد هوڤر واحد من أعلى السدود الإسمنتية في العالم. يقع هذا السد في الوادي الأسود لنهر كولورادو، بأريزونا، بالولايات المتحدة. وهو جزء من مشروع وادي الجلمود. يشمل المشروع إقامة سد، ووحدة هيدروكهربائية لتوليد الطاقة وإقامة خزان، ويقوم بضبط فيضانات نهر كولورادو، كما يزَوِّد مساحة كبيرة من جنوب غربي الأطلسي بالمياه المحلية ومياه الري والقدرة الكهربائية.

يبلغ ارتفاع سد هوفر 221م وطوله 379م. وتهبط المصاعد ما يعادل 44 طابقًا داخل السد دون أن تصل إلى قاعدته. ويبلغ سُمك السد 200م. ويحتوي على أكثر من 3,360,000م§ من الإسمنت.

وبحيرة ميد تشكل خزان السد، وهي واحدة من أكبر الأجسام المائية الاصطناعية في العالم. يبلغ طولها نحو 185 كم، وعمقها 180م، ويحجز الخزان نحو 36,702,300,000م§ من الماء.

خلفية

البحث عن مصادر

التخطيط والاتفاقيات

التصميم والتحضير والتعاقد

في بداية القرن العشرين كانت الحاجة ماسة لإقامة سد على نهر كولورادو؛ حيث كانت الفيضانات تسبب الكثير من الخسائر في وادي بالو فيردي والوادي الملكي.

تم بناء الحواجز بصورة مكثفة، ولكن المحاصيل كانت تموت عندما تنخفض المياه، ولا تغطي احتياجات المنطقة من مياه الري.

وفي عام 1928، أجاز الكونجرس مشروع وادي الجلمود.

الإنشاء

القوى العاملة

وقد بدأ إنشاء السد في 30 سبتمبر 1935 في بولدر سيتي، نـِڤادا. سد القوس الخرساني الذي سمي "سد هوڤر" عام 1947 كان جزءاً من أول محطة طاقة مائية في الولايات المتحدة بقدرة مليون كيلو واط. تلك الطاقة القصوى وصل إليها في يونيو 1943، بالرغم من أن أول مولداته الأربعة بدأ العمل في 26 أكتوبر 1936. الطاقة تخدم منطقة لوس أنجلس.

اكتمل بناء السد في عام 1936 وأطلق عليه اسم سد هوفر تكريمًا للرئيس هربرت هوڤر.

|valign="top"|

|}

التشغيل

توزيع الكهرباء

Electricity from the dam's powerhouse was originally sold pursuant to a fifty-year contract, authorized by Congress in 1934, which ran from 1937 to 1987. In 1984, Congress passed a new statute which set power allocations to southern California, Arizona, and Nevada from the dam from 1987 to 2017.[6][7] The powerhouse was run under the original authorization by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power and Southern California Edison; in 1987, the Bureau of Reclamation assumed control.[8] In 2011, Congress enacted legislation extending the current contracts until 2067, after setting aside 5% of Hoover Dam's power for sale to Native American tribes, electric cooperatives, and other entities. The new arrangement began on October 1, 2017.[6]

The Bureau of Reclamation reports that the energy generated under the contracts ending in 2017 was allocated as follows:[4]

|

|

المفايض

The dam is protected against over-topping by two spillways. The spillway entrances are located behind each dam abutment, running roughly parallel to the canyon walls. The spillway entrance arrangement forms a classic side-flow weir with each spillway containing four 100-قدم-long (30 m) and 16-قدم-wide (4.9 m) steel-drum gates. Each gate weighs 5،000،000 رطل (2،300 metric ton) and can be operated manually or automatically. Gates are raised and lowered depending on water levels in the reservoir and flood conditions. The gates cannot entirely prevent water from entering the spillways but can maintain an extra 16 ft (4.9 m) of lake level.[9]

Water flowing over the spillways falls dramatically into 600-قدم-long (180 m), 50-قدم-wide (15 m) spillway tunnels before connecting to the outer diversion tunnels, and reentering the main river channel below the dam. This complex spillway entrance arrangement combined with the approximate 700-قدم (210 m) elevation drop from the top of the reservoir to the river below was a difficult engineering problem and posed numerous design challenges. Each spillway's capacity of 200،000 cu ft/s (5،700 m3/s) was empirically verified in post-construction tests in 1941.[9]

The large spillway tunnels have only been used twice, for testing in 1941 and because of flooding in 1983. Both times, when inspecting the tunnels after the spillways were used, engineers found major damage to the concrete linings and underlying rock.[10] The 1941 damage was attributed to a slight misalignment of the tunnel invert (or base), which caused cavitation, a phenomenon in fast-flowing liquids in which vapor bubbles collapse with explosive force. In response to this finding, the tunnels were patched with special heavy-duty concrete and the surface of the concrete was polished mirror-smooth.[11] The spillways were modified in 1947 by adding flip buckets, which both slow the water and decrease the spillway's effective capacity, in an attempt to eliminate conditions thought to have contributed to the 1941 damage. The 1983 damage, also due to cavitation, led to the installation of aerators in the spillways.[10] Tests at Grand Coulee Dam showed that the technique worked, in principle.[11]

الطريق والسياحة

There are two lanes for automobile traffic across the top of the dam, which formerly served as the Colorado River crossing for U.S. Route 93.[12] In the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks, authorities expressed security concerns and the Hoover Dam Bypass project was expedited. Pending the completion of the bypass, restricted traffic was permitted over Hoover Dam. Some types of vehicles were inspected prior to crossing the dam while semi-trailer trucks, buses carrying luggage, and enclosed-box trucks over 40 ft (12 m) long were not allowed on the dam at all, and were diverted to U.S. Route 95 or Nevada State Routes 163/68.[13] The four-lane Hoover Dam Bypass opened on October 19, 2010.[14] It includes a composite steel and concrete arch bridge, the Mike O'Callaghan–Pat Tillman Memorial Bridge, 1،500 ft (460 m) downstream from the dam. With the opening of the bypass, through traffic is no longer allowed across Hoover Dam; dam visitors are allowed to use the existing roadway to approach from the Nevada side and cross to parking lots and other facilities on the Arizona side.[15]

Hoover Dam opened for tours in 1937 after its completion, but following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, it was closed to the public when the United States entered World War II, during which only authorized traffic, in convoys, was permitted. After the war, it reopened September 2, 1945, and by 1953, annual attendance had risen to 448,081. The dam closed on November 25, 1963, and March 31, 1969, days of mourning in remembrance of Presidents Kennedy and Eisenhower. In 1995, a new visitors' center was built, and the following year, visits exceeded one million for the first time. The dam closed again to the public on September 11, 2001; modified tours were resumed in December and a new "Discovery Tour" was added the following year.[8] Today, nearly a million people per year take the tours of the dam offered by the Bureau of Reclamation.[16] Increased security concerns by the government have led to most of the interior structure's being inaccessible to tourists. As a result, few of True's decorations can now be seen by visitors.[17] Visitors can only purchase tickets on-site and have the options of a guided tour of the whole facility or only the power plant area. The only self-guided tour option is for the visitor center itself, where visitors can view various exhibits and enjoy a 360-degree view of the dam.[18]

الوقع البيئي

The changes in water flow and use caused by Hoover Dam's construction and operation have had a large impact on the Colorado River Delta.[19] The construction of the dam has been implicated in causing the decline of this estuarine ecosystem.[19] For six years after the construction of the dam, while Lake Mead filled, virtually no water reached the mouth of the river.[20] The delta's estuary, which once had a freshwater-saltwater mixing zone stretching 40 ميل (64 km) south of the river's mouth, was turned into an inverse estuary where the level of salinity was higher close to the river's mouth.[21]

The Colorado River had experienced natural flooding before the construction of the Hoover Dam. The dam eliminated the natural flooding, threatening many species adapted to the flooding, including both plants and animals.[22] The construction of the dam devastated the populations of native fish in the river downstream from the dam.[23] Four species of fish native to the Colorado River, the Bonytail chub, Colorado pikeminnow, Humpback chub, and Razorback sucker, are listed as endangered.[24][25]

التكريم

Hoover Dam was recognized as a National Civil Engineering Landmark in 1984.[26] It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1981, and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1985, cited for its engineering innovations.[2]

انظر أيضاً

- Ralph Luther Criswell, lobbyist on behalf of the dam

- Glen Canyon Dam

- شرطة سد هوڤر

- List of dams in the Colorado River system

- List of largest hydroelectric power stations

- List of largest hydroelectric power stations in the United States

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Arizona

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Nevada

- St. Thomas, Nevada, ghost town with site now under Lake Mead.

- Water in California

المصادر

- ^ "Inventory-Nomination form: Hoover Dam" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ^ أ ب "Hoover Dam". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions: Lake Mead". Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةpowerfaq - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةhovart - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةLien-Mager 2011 - ^ "House, after stiff debate, backs cheap power for 3 Western states". The New York Times. May 4, 1984. Archived from the original on April 2, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ أ ب Bureau of Reclamation 2006, pp. 50–52.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةrecspi - ^ أ ب Fiedler 2010.

- ^ أ ب Hiltzik 2010, pp. 391–392.

- ^ Sean Holstege (October 17, 2010). "Hoover Dam Bypass an American Triumph". azcentral.com.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةUSBR, Crossing Hoover - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHansen 2010-10-20 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةhdbfaq - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةUSBR, Hoover Tour - ^ Hiltzik 2010, p. 379.

- ^ Karyn Wofford (3 December 2018). "The Hoover Dam – Everything You Need to Know About Visiting". Trips to Discover. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ أ ب Glenn Lee et al. 1996.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBurns 2001 - ^ Rodriguez Flessa et al. 2001.

- ^ Schmidt Webb et al. 1998.

- ^ Cohn 2001.

- ^ Minckley Marsh et al. 2003.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةFWS, Colorado River Recovery - ^ Rogers, Wiltshire & Gilbert 2011.

فهرس

- Duchemin, Michael (2009). "Water, Power, and Tourism: Hoover Dam and the Making of the New West". California History. 86 (4): 60–78. ISSN 0162-2897.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dunar, Andrew J.; McBride, Dennis (2001) [1993]. Building Hoover Dam: An Oral History of the Great Depression. Reno, Nev.: University of Nevada Press. ISBN 0-87417-489-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hiltzik, Michael A. (2010). Colossus: Hoover Dam and the Making of the American Century. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-1-4165-3216-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stevens, Joseph E. (1988). Hoover Dam: An American Adventure. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2283-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - True, Jere; Kirby, Victoria Tupper (2009). Allen Tupper True: An American Artist. San Francisco: Canyon Leap. ISBN 978-0-9817238-1-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bureau of Reclamation (2006). Reclamation: Managing Water in the West: Hoover Dam. US Department of the Interior.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

وصلات خارجية

- Hoover Dam's official website

- Official State of Nevada Tourism Site

- The story of Hoover Dam video - Bureau of Reclamation

- Historic Construction Company Project – Hoover Dam

- Hoover Dam in the Structurae database

- BBC – Hoover Dam, industrial and social history

- Frank Crowe – Builder of Hoover Dam

- "Boulder Dam" – Part I and Parts III and IV, documentary films from the Prelinger Archives at the Internet Archive.

- PBS American experience – Hoover Dam

- Boulder City / Hoover Dam Museum official site

[[تصنيف:نهر كولورادو]

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using infobox NRHP with unknown parameters

- Pages using infobox dam with unknown parameters

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages with empty portal template

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Art Deco architecture in Arizona

- مباني ومنشآت في نـِڤادا

- سدود أريزونا

- سدود نـِڤادا

- Dams on the National Register of Historic Places

- Arch-gravity dams

- Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks

- Hydroelectric power plants in Arizona

- Hydroelectric power plants in Nevada

- Buildings and structures in Mohave County, Arizona

- National Historic Landmarks in Arizona

- National Historic Landmarks in Nevada

- Buildings and structures completed in 1936

- Buildings and monuments honoring American Presidents

- مشاريع هندسية

- Visitor attractions in Mohave County, Arizona

- U.S. Route 93