ستكسنت

ستكسنت Stuxnet، هو دودة حاسوب اكتشفت في يونيو 2010 يعتقد بأن الولايات المتحدة وإسرائيل استخدمتها للهجوم على المرافق النووية الإيرانية. تنتشر ستكسنت في البداية عبر الويندوز، وتستهدف برمجيات ومعدات سيمنز الصناعية. بينما لم تكن تلك هي المرة الأولى التي يستخدف فيها الهاكرز الأنظمة الصناعية،[1] فتلك هي المرة الأولى التي يكتشف فيها برمجيات خبيثة تقوم بالتتجس وتخريب أنظمة صناعية،[2] والتي تحتوي لأول مرة على جهاز تحكم منطقي قابل للبرمجة(PLC) روتکیت.[3][4]

في البداية تنتشر الدودة بشكل عشوائي، في الوقت الذي تحمل فيه عدد كبير من البرمجيات الخبيثة المتخصصة المصممة التي تستهدف فقط أنظمة نظام التحكم الإشرافي وتحصيل البيانات من سيمنز المسئولة عن مراقبة ورصد عمليات صناعية محددة.[5][6] يصيب ستكسنت أجهزة الحاسوب عن طريق تعطيل تطبيقات ستپ-7 التي تستخدم لإعادة برمجة هذه الأجهزة.[7][8]

استهدفت أنواع مختلفة من ستكسنت خمس منمات إيرانية،[9] مع التركيز على الهجوم على مرافق تخصيب اليورانيوم في إيران؛[8][10][11] رصدت سيمانتك في أغسطس 2010 تعرض 60% من الحواسب الإيرانية للهجوم.[12] أعلنت سيمنز أن الدودة تسببت في أضرار لعملائها،[13] لكن البرنامج النووي الإيراني، والذي يستخدم معدات سيمنز المحظورة وتم شراؤها بطريقة سرية، تعرض لأضرار بعد تعرضه لهجمات ستكسنت.[14][15] أكد معمل كاسپرسكي أن هذا الهجوم المتطور لابد وأن يكون مرتبط "بتدعيم حكومي".[16] فيما بعد أكد هذا الاعتقاد ميكو هيپونن كبير باحثي إف-سكيور، معلقاً على الهجمات "على ما يبدو أن هذا صحيح".[17] وقد تردد عن تورط إسرائيل[18] ويحتمل أن تكون الولايات المتحدة أيضاً متورطة في الهجمات.[19][20]

في مايو 2010، استشهد برنامج پيبيإس بحاجة للمعرفة بتصريح گراي سامور، منسق البيت الأبيض لأسلحة الدمار الشامل، والذي قال فيه، "نحن سعداء لأن [الإيرانيين] لديهم مشكلة في معدات الطرد المركزية الخاصة بهم وأننا - الولاية المتحدة وحلفائها - نفعل كل ما نستطيع فعله لنتسبب في تعقيد مشكلاتهم"، كإعتراف ضمني على تورط الولايات المتحدة في هجمات ستكسنت.[21] حسب دايلي تليگراف، في تسجيل قصير في حفل المتقاعدين، لرئيس جيش الدفاع الإسرائيلي گابي أشكنازي، تضمن الإشارة إلى ستكسنت كأحد النجاحات التي حققها رئيس أركان جيش الدفاع.[18]

في 1 يونيو 2012، في مقالة نشرتها نيويورك تايمز أن ستكسنت جزء من عملية مخابراتية أمريكية إسرائلية تسمى "عملية الألعاب الأولمپية"، بدأت في عهد جورج دبليو بوش وامتدت حتى تولي باراك اوباما الحكم.[22]

في 24 يوليو 2012، في مقال لكريس ماتيزيزيك من سنت[23] والتي وضح فيها كيف أرسلت رسالة إلكترونية من منظمة الطاقة النووية الإيرانية إلى رئيس إف-سكيور ميكو هيپونن للإبلاغ عن نوع جديد من البرمجيات الخبيثة.

في 25 ديسمبر 2012، أعلنت وكالة أخبار شبه رسمية إيرانية عن وقوع هجمة إلكترونية بستكسنت، على مرافق صناعية في جنوب البلاد. استهدف الڤيروس محطة طاقة وبعض المرافق الصناعية الأخرى في محافظة هرمزگان خلال الأشهر الأخيرة.[24]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ

تم التعرف على الدودة لأول مرة من قبل شركة ڤيروسبلوكأدا في منتصف يونيو 2010.[7] على مدونة الصحفي بريان كربس في 15 يوليو 2010، نُشر لأول مرة تقرير انتشر بسرعة كبيرة عن الدودة.[25][26] اشتق اسمها من بعض الكلامات المفتاحية التي اكتشفت في البرنامج.[8][27] ويعزى السبب في اكتشاف في ذلك الوقت لانتشار الڤيروس عن طريق الخطأ، بعيداً عن الهدف المقصود (محطة نتانز) لخطأ في البرمجة ظهر عند التحديث؛ أدى هذا إلى انتشار الدودة في فيروس أحد المهندسين كان موصلاً بأجهزة الطرد المركزي، ثم انتشر عندما عاد المهندس لمنزله وقام بإيصال الحاسوب بالإنترنت.[22]

قدر خبراء معمل كاسپرسكي أن بداية انتشار ستكسنت لأول مرة كانت في مارس أو أبريل 2010،[28] وظهرت أول أنواع الدودة لأول مرة في يونيو 2009.[7] في 15 يوليو 2010، انتشرت أخبار وجود الدودة بشكل كبير، ووقع هجمات الحرمان من الخدمة على خوادم إثنتين من القوائم البريدية الرئيسية في أمن النظم الصناعية. جاء هذا الهجوم من مصدر غير معروف لكن يعتقد أنه مرتبط بستكسنت.

البلدان المتأثرة

في دراسة عن انتشار ستكسنت قامت بها سيمنتك وضحت فيها البلدان الرئيسية المتأثرة في الأيام الأولى للهجمات التي تعرضت لها إيران، إندونسيا والهند:[29]

| البلد | الحواسب الموبوءة |

|---|---|

| 58.85% | |

| 18.22% | |

| 8.31% | |

| 2.57% | |

| 1.56% | |

| 1.28% | |

| أخرى | 9.2% |

أسلوب الهجوم

| “ | [O]ne of the great technical blockbusters in malware history. | ” |

—Vanity Fair, April 2011[26] | ||

تستهدف الدودة الأنظمة التالية:

- أنظمة تشغيل ويندوز

- تطبيقات البرمجيات الصناعية سيمنز پيسيإس 7، وينسيسي وإستيإيپي7 التي تعمل على نظام تشغيل ويندوز

- واحدة أو أكثر من أجهزة سيمنز إس7 پيإلسيإس

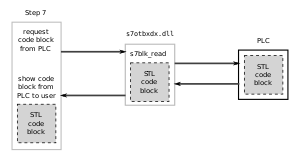

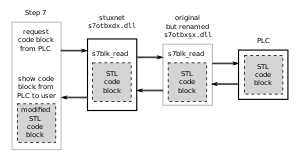

According to researcher Ralph Langner,[30][31] once installed on a Windows system Stuxnet infects project files belonging to Siemens' WinCC/PCS 7 SCADA control software[32] (Step 7), and subverts a key communication library of WinCC called s7otbxdx.dll. Doing so intercepts communications between the WinCC software running under Windows and the target Siemens PLC devices that the software is able to configure and program when the two are connected via a data cable. In this way, the malware is able to install itself on PLC devices unnoticed, and subsequently to mask its presence from WinCC if the control software attempts to read an infected block of memory from the PLC system.[33]

إزالتها

Siemens has released a detection and removal tool for Stuxnet. Siemens recommends contacting customer support if an infection is detected and advises installing Microsoft patches for security vulnerabilities and prohibiting the use of third-party USB flash drives.[34] Siemens also advises immediately upgrading password access codes.[35]

أمن نظام التحكم

Prevention of control system security incidents,[36] such as from viral infections like Stuxnet, is a topic that is being addressed in both the public and the private sector.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security National Cyber Security Division (NCSD) operates the Control System Security Program (CSSP).[37] The program operates a specialized computer emergency response team called the Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team (ICS-CERT), conducts a biannual conference (ICSJWG), provides training, publishes recommended practices, and provides a self-assessment tool. As part of a Department of Homeland Security plan to improve American computer security, in 2008 it and the Idaho National Laboratory (INL) worked with Siemens to identify security holes in the company's widely used Process Control System 7 (PCS 7) and its software Step 7. In July 2008, INL and Siemens publicly announced flaws in the control system at a Chicago conference; Stuxnet exploited these holes in 2009.[38]

Several industry organizations[39][40] and professional societies[41][42] have published standards and best practice guidelines providing direction and guidance for control system end-users on how to establish a control system security management program. The basic premise that all of these documents share is that prevention requires a multi-layered approach, often referred to as "defense-in-depth".[43] The layers include policies and procedures, awareness and training, network segmentation, access control measures, physical security measures, system hardening, e.g., patch management, and system monitoring, anti-virus and intrusion prevention system (IPS). The standards and best practices[من؟] also allقالب:Synthesis-inline recommend starting with a risk analysis and a control system security assessment.[44][45]

التكهنات حول الهدف والمنشأ

Experts believe that Stuxnet required the largest and costliest development effort in malware history.[26] Its many capabilities would have required a team of people to program, in-depth knowledge of industrial processes, and an interest in attacking industrial infrastructure.[2][7] Eric Byres, who has years of experience maintaining and troubleshooting Siemens systems, told Wired that writing the code would have taken many man-months, if not years.[46] Symantec estimates that the group developing Stuxnet would have consisted of anywhere from five to thirty people, and would have taken six months to prepare.[47][26] The Guardian, the BBC and The New York Times all claimed that (unnamed) experts studying Stuxnet believe the complexity of the code indicates that only a nation-state would have the capabilities to produce it.[10][47][48] The self-destruct and other safeguards within the code imply that a Western government was responsible, with lawyers evaluating the worm's ramifications.[26] Software security expert Bruce Schneier condemned the 2010 news coverage of Stuxnet as hype, however, stating that it was almost entirely based on speculation.[49] But after subsequent research, Schneier stated in 2012 that "we can now conclusively link Stuxnet to the centrifuge structure at the Natanz nuclear enrichment lab in Iran".[50]

إيران كهدف

Ralph Langner, the researcher who identified that Stuxnet infected PLCs,[8] first speculated publicly in September 2010 that the malware was of Israeli origin, and that it targeted Iranian nuclear facilities.[51] However Langner more recently, in a TED Talk recorded in February 2011, stated that, "My opinion is that the Mossad is involved, but that the leading force is not Israel. The leading force behind Stuxnet is the cyber superpower – there is only one; and that's the United States."[52] Kevin Hogan, Senior Director of Security Response at Symantec, reported that the majority of infected systems were in Iran (about 60%),[53] which has led to speculation that it may have been deliberately targeting "high-value infrastructure" in Iran[10] including either the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant or the Natanz nuclear facility.[46][54][55] Langner called the malware "a one-shot weapon" and said that the intended target was probably hit,[56] although he admitted this was speculation.[46] Another German researcher, Frank Rieger, was the first to speculate that Natanz was the target.[26]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

مرافق نتانز النووية

According to the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, in September 2010 experts on Iran and computer security specialists were increasingly convinced that Stuxnet was meant "to sabotage the uranium enrichment facility at Natanz – where the centrifuge operational capacity has dropped over the past year by 30 percent."[57] On 23 November 2010 it was announced that uranium enrichment at Natanz had ceased several times because of a series of major technical problems.[58][59] A "serious nuclear accident" (supposedly the shutdown of some of its centrifuges[60]) occurred at the site in the first half of 2009, which is speculated to have forced the head of Iran's Atomic Energy Organization Gholam Reza Aghazadeh to resign.[61] Statistics published by the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) show that the number of enrichment centrifuges operational in Iran mysteriously declined from about 4,700 to about 3,900 beginning around the time the nuclear incident WikiLeaks mentioned would have occurred.[62] (ISIS) suggests, in a report published in December 2010, that Stuxnet is "a reasonable explanation for the apparent damage"[63] at Natanz, and may have destroyed up to 1000 centrifuges (10 percent) sometime between November 2009 and late January 2010. The authors conclude:

The attacks seem designed to force a change in the centrifuge’s rotor speed, first raising the speed and then lowering it, likely with the intention of inducing excessive vibrations or distortions that would destroy the centrifuge. If its goal was to quickly destroy all the centrifuges in the FEP [Fuel Enrichment Plant], Stuxnet failed. But if the goal was to destroy a more limited number of centrifuges and set back Iran’s progress in operating the FEP, while making detection difficult, it may have succeeded, at least temporarily.[63]

The (ISIS) report further notes that Iranian authorities have attempted to conceal the breakdown by installing new centrifuges on a large scale.[63][64]

The worm worked by first causing an infected Iranian IR-1 centrifuge to increase from its normal operating speed of 1,064 hertz to 1,410 hertz for 15 minutes before returning to its normal frequency. Twenty-seven days later, the worm went back into action, slowing the infected centrifuges down to a few hundred hertz for a full 50 minutes. The stresses from the excessive, then slower, speeds caused the aluminum centrifugal tubes to expand, often forcing parts of the centrifuges into sufficient contact with each other to destroy the machine.[65]

According to The Washington Post, (IAEA) cameras installed in the Natanz facility recorded the sudden dismantling and removal of approximately 900–1000 centrifuges during the time the Stuxnet worm was reportedly active at the plant. Iranian technicians, however, were able to quickly replace the centrifuges and the report concluded that uranium enrichment was likely only briefly disrupted.[66]

On 15 February 2011, (ISIS) released a report concluding that:

Assuming Iran exercises caution, Stuxnet is unlikely to destroy more centrifuges at the Natanz plant. Iran likely cleaned the malware from its control systems. To prevent re-infection, Iran will have to exercise special caution since so many computers in Iran contain Stuxnet. Although Stuxnet appears to be designed to destroy centrifuges at the Natanz facility, destruction was by no means total. Moreover, Stuxnet did not lower the production of LEU during 2010. LEU quantities could have certainly been greater, and Stuxnet could be an important part of the reason why they did not increase significantly. Nonetheless, there remain important questions about why Stuxnet destroyed only 1,000 centrifuges. One observation is that it may be harder to destroy centrifuges by use of cyber attacks than often believed.[63]

رد الفعل الإيراني

The Associated Press reported that the semi-official Iranian Students News Agency released a statement on 24 September 2010 stating that experts from the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran met in the previous week to discuss how Stuxnet could be removed from their systems.[6] According to analysts, such as David Albright, Western intelligence agencies have been attempting to sabotage the Iranian nuclear program for some time.[67][68]

The head of the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant told Reuters that only the personal computers of staff at the plant had been infected by Stuxnet and the state-run newspaper Iran Daily quoted Reza Taghipour, Iran's telecommunications minister, as saying that it had not caused "serious damage to government systems".[48] The Director of Information Technology Council at the Iranian Ministry of Industries and Mines, Mahmud Liaii, has said that: "An electronic war has been launched against Iran... This computer worm is designed to transfer data about production lines from our industrial plants to locations outside Iran."[69]

In response to the infection, Iran has assembled a team to combat it. With more than 30,000 IP addresses affected in Iran, an official has said that the infection is fast spreading in Iran and the problem has been compounded by the ability of Stuxnet to mutate. Iran has set up its own systems to clean up infections and has advised against using the Siemens SCADA antivirus since it is suspected that the antivirus is actually embedded with codes which update Stuxnet instead of eradicating it.[70][71][72][73]

According to Hamid Alipour, deputy head of Iran's government Information Technology Company, "The attack is still ongoing and new versions of this virus are spreading." He reports that his company had begun the cleanup process at Iran's "sensitive centres and organizations."[71] "We had anticipated that we could root out the virus within one to two months, but the virus is not stable, and since we started the cleanup process three new versions of it have been spreading," he told the Islamic Republic News Agency on 27 September 2010.[73]

On 29 November 2010, Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad stated for the first time that a computer virus had caused problems with the controller handling the centrifuges at its Natanz facilities. According to Reuters he told reporters at a news conference in Tehran, "They succeeded in creating problems for a limited number of our centrifuges with the software they had installed in electronic parts."[74][75]

On the same day two Iranian nuclear scientists were targeted in separate, but nearly simultaneous car bomb attacks near Shahid Beheshti University in Tehran. Majid Shahriari, a quantum physicist was killed. Fereydoon Abbasi, a high-ranking official at the Ministry of Defense was seriously wounded. Wired speculated that the assassinations could indicate that whoever was behind Stuxnet felt that it was not sufficient to stop the nuclear program.[76] In January 2010, another Iranian nuclear scientist, a physics professor at Tehran University, had been killed in a similar bomb explosion.[76] On 11 January 2012, a Director of the Natanz nuclear enrichment facility, Mostafa Ahmadi Roshan, was killed in an attack quite similar to the one that killed Shahriari.[77]

An analysis by the FAS demonstrates that Iran’s enrichment capacity grew during 2010. The study indicates that Iran’s centrifuges appear to be performing 60% better than in the previous year, which would significantly reduce Tehran’s time to produce bomb-grade uranium. The FAS report was reviewed by an official with the IAEA who affirmed the study.[78][79][80]

European and U.S. officials, along with private experts, have told Reuters that Iranian engineers were successful in neutralizing and purging Stuxnet from their country's nuclear machinery.[81]

Given the growth in Iranian enrichment capability in 2010, the country may have intentionally put out misinformation to cause Stuxnet's creators to believe that the worm was more successful in disabling the Iranian nuclear program than it actually was.[26]

إسرائيل

Israel, through Unit 8200,[82][83] has been speculated to be the country behind Stuxnet in many media reports[47][60][84] and by experts such as Richard A. Falkenrath, former Senior Director for Policy and Plans within the U.S. Office of Homeland Security.[85][48] Yossi Melman, who covers intelligence for the Israeli daily newspaper Haaretz and is writing a book about Israeli intelligence, also suspected that Israel was involved, noting that Meir Dagan, the former (2011) head of the national intelligence agency Mossad, had his term extended in 2009 because he was said to be involved in important projects. Additionally, Israel now expects that Iran will have a nuclear weapon in 2014 or 2015 – at least three years later than earlier estimates – without the need for an Israeli military attack on Iranian nuclear facilities; "They seem to know something, that they have more time than originally thought”, he added.[15][38] Israel has not publicly commented on the Stuxnet attack but confirmed that cyberwarfare is now among the pillars of its defense doctrine, with a military intelligence unit set up to pursue both defensive and offensive options.[86][87][88] When questioned whether Israel was behind the virus in the fall of 2010, some Israeli officials[من؟] broke into "wide smiles", fueling speculation that the government of Israel was involved with its genesis.[89] American presidential advisor Gary Samore also smiled when Stuxnet was mentioned,[38] although American officials have indicated that the virus originated abroad.[89] According to The Telegraph, Israeli newspaper Haaretz reported that a video celebrating operational successes of Gabi Ashkenazi, retiring IDF Chief of Staff, was shown at his retirement party and included references to Stuxnet, thus strengthening claims that Israel's security forces were responsible.[90]

In 2009, a year before Stuxnet was discovered, Scott Borg of the United States Cyber-Consequences Unit (US-CCU)[91] suggested that Israel might prefer to mount a cyber-attack rather than a military strike on Iran's nuclear facilities.[68] And, in late 2010 Borg stated, "Israel certainly has the ability to create Stuxnet and there is little downside to such an attack, because it would be virtually impossible to prove who did it. So a tool like Stuxnet is Israel's obvious weapon of choice."[27] Iran uses P-1 centrifuges at Natanz, the design for which A. Q. Khan stole in 1976 and took to Pakistan. His black market nuclear-proliferation network sold P-1s to, among other customers, Iran. Experts believe that Israel also somehow acquired P-1s and tested Stuxnet on the centrifuges, installed at the Dimona facility that is part of its own nuclear program.[38] The equipment may be from the United States, which received P-1s from Libya's former nuclear program.[92][38]

Some have also referred to several clues in the code such as a concealed reference to the word "MYRTUS", believed to refer to the Myrtle tree, or Hadassah in Hebrew. Hadassah was the birth name of the former Jewish queen of Persia, Queen Esther.[93][94] However, it may be that the "MYRTUS" reference is simply a misinterpreted reference to SCADA components known as RTUs (Remote Terminal Units) and that this reference is actually "My RTUs"–a management feature of SCADA.[95] Also, the number 19790509 appears once in the code and might refer to the date "1979 May 09", the day Habib Elghanian, a Persian Jew, was executed in Tehran.[33][96][97] Another date that appears in the code is "24 September 2007", the day that Iran's president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad spoke at Columbia University and made comments questioning the validity of the Holocaust.[26] Such data is not conclusive, since, as written by Symantec, "Attackers would have the natural desire to implicate another party" with a false flag.[26][33]

الولايات المتحدة

There has also been speculation on the involvement of the United States,[98] with one report stating that "there is vanishingly little doubt that [it] played a role in creating the worm."[26] It has been reported that the United States, under one of its most secret programs, initiated by the Bush administration and accelerated by the Obama administration, has sought to destroy Iran's nuclear program by novel methods such as undermining Iranian computer systems. A diplomatic cable obtained by WikiLeaks showed how the United States was advised to target Iran's nuclear capabilities through 'covert sabotage'.[99] A Wired article claimed that Stuxnet "is believed to have been created by the United States".[100] The fact that John Bumgarner, a former intelligence officer and member of the United States Cyber-Consequences Unit ([US-CCU), published an article prior to Stuxnet being discovered or deciphered, that outlined a strategic cyberstrike on centrifuges[101] and suggests that cyber attacks are permissible against nation states which are operating uranium enrichment programs that violate international treaties gives some credibility to these claims. Bumgarner pointed out that the centrifuges used to process fuel for nuclear weapons are a key target for cybertage operations and that they can be made to destroy themselves by manipulating their rotational speeds.[102]

In a March 2012 interview with CBS News' "60 Minutes," retired USAF general Michael Hayden – who served as director of both the Central Intelligence Agency and National Security Agency – while denying knowledge of who created Stuxnet said that he believed it had been "a good idea" but that it carried a downside in that it had legitimized the use of sophisticated cyberweapons designed to cause physical damage. Hayden said, "There are those out there who can take a look at this… and maybe even attempt to turn it to their own purposes." In the same report, Sean McGurk, a former cybersecurity official at the Department of Homeland Security noted that the Stuxnet source code could now be downloaded online and modified to be directed at new target systems. Speaking of the Stuxnet creators, he said, "They opened the box. They demonstrated the capability… It's not something that can be put back."[103]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الجهود المشتركة والدول الأخرى والأهداف

In April 2011 Iranian government official Gholam Reza Jalali stated that an investigation had concluded that the United States and Israel were behind the Stuxnet attack.[104] According to Vanity Fair, Rieger stated that three European countries' intelligence agencies agreed that Stuxnet was a joint United States-Israel effort. The code for the Windows injector and the PLC payload differ in style, likely implying collaboration. Other experts believe that a US-Israel cooperation is unlikely because "the level of trust between the two countries’ intelligence and military establishments is not high."[26]

China,[105] Jordan, and فرنسا are other possibilities, and Siemens may have also participated.[26][98] Langner speculated that the infection may have spread from USB drives belonging to Russian contractors since the Iranian targets were not accessible via the internet.[8][106]

Sandro Gaycken from the Free University Berlin argued that the attack on Iran was a ruse to distract from Stuxnet's real purpose. According to him, its broad dissemination in more than 100,000 industrial plants worldwide suggests a field test of a cyber weapon in different security cultures, testing their preparedness, resilience, and reactions, all highly valuable information for a cyberwar unit.[107]

The المملكة المتحدة has denied involvement in the virus's creation.[108]

Stratfor Documents released by Wikileaks suggest that the International Security Firm 'Stratfor' believe that Israel is behind Stuxnet - "But we can't assume that because they did stuxnet that they are capable of doing this blast as well."[109]

دوكو

On 1 September 2011, a new worm was found, thought to be related to Stuxnet. The Laboratory of Cryptography and System Security (CrySyS) of the Budapest University of Technology and Economics analyzed the malware, naming the threat Duqu.[110][111] Symantec, based on this report, continued the analysis of the threat, calling it "nearly identical to Stuxnet, but with a completely different purpose", and published a detailed technical paper.[112] The main component used in Duqu is designed to capture information[20] such as keystrokes and system information. The exfiltrated data may be used to enable a future Stuxnet-like attack. On 28 December 2011, Kaspersky Lab's director of global research and analysis spoke to Reuters about recent research results showing that the platform Stuxnet and Duqu both were built on originated in 2007, and is being referred to as Tilded due to the ~d at the beginning of the file names. Also uncovered in this research was the possibility for three more variants based on the Tilded platform.[113]

فلام

In May 2012, the new malware "Flame" was found, thought to be related to Stuxnet.[114] Researchers named the program "Flame" after the name of one of its modules.[114] After analysing the code of Flame, Kaspersky said that there is a strong relationship between Flame and Stuxnet. An early version of Stuxnet contained code to propagate infections via USB drives that is nearly identical to a Flame module that exploits the same vulnerability.[115]

انظر أيضاً

- حرب الإنترنت

- قياسيات أمن الإنترنت

- إرهاب إلكتروني

- حرب الإنترنت في الولايات المتحدة

- فلام

- كيلر پوك

- قائمة هجمات الإنترنت

- مهدي

- العملية مرلين

- دفاع الإنترنت الإستباقي

- الڤيروس ستارز

- قيادة الإنترنت الأمريكية

المصادر

- ^ "Building a Cyber Secure Plant". Siemens. 30 September 2010. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ^ أ ب Robert McMillan (16 September 2010). "Siemens: Stuxnet worm hit industrial systems". Computerworld. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ "Last-minute paper: An indepth look into Stuxnet". Virus Bulletin.

- ^ "Stuxnet worm hits Iran nuclear plant staff computers". BBC News. 26 September 2010.

- ^ Nicolas Falliere (6 August 2010). "Stuxnet Introduces the First Known Rootkit for Industrial Control Systems". Symantec.

- ^ أ ب "Iran's Nuclear Agency Trying to Stop Computer Worm". Tehran. Associated Press. 25 September 2010. Archived from the original on 25 September 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Gregg Keizer (16 September 2010). "Is Stuxnet the 'best' malware ever?". Infoworld. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Steven Cherry, with Ralph Langner (13 October 2010). "How Stuxnet Is Rewriting the Cyberterrorism Playbook". IEEE Spectrum.

- ^ "Stuxnet Virus Targets and Spread Revealed". BBC News. 15 February 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت Fildes, Jonathan (23 September 2010). "Stuxnet worm 'targeted high-value Iranian assets'". BBC News. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ Beaumont, Claudine (23 September 2010). "Stuxnet virus: worm 'could be aimed at high-profile Iranian targets'". London: The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ MacLean, William (24 September 2010). "UPDATE 2-Cyber attack appears to target Iran-tech firms". Reuters.

- ^ ComputerWorld (14 September 2010). "Siemens: Stuxnet worm hit industrial systems". Computerworld. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ "Iran Confirms Stuxnet Worm Halted Centrifuges". CBS News. 29 November 2010.

- ^ أ ب Ethan Bronner & William J. Broad (خطأ: لا توجد وحدة بهذا الاسم "month translator".). "In a Computer Worm, a Possible Biblical Clue". NYTimes (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved خطأ: لا توجد وحدة بهذا الاسم "month translator"..

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help); Check date values in:|access-date=,|date=, and|archive-date=(help)"Software smart bomb fired at Iranian nuclear plant: Experts". Economictimes.indiatimes.com. 24 September 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2010. - ^ "Kaspersky Lab provides its insights on Stuxnet worm". Kaspersky. Russia. 24 September 2010.

- ^ "Stuxnet Questions and Answers - F-Secure Weblog". F-Secure. Finland. 1 October 2010.

- ^ أ ب Williams, Christopher (15 February 2011). "Israel video shows Stuxnet as one of its successes". London: Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ Markoff, John (11 February 2011). "Malware Aimed at Iran Hit Five Sites, Report Says". New York Times. p. 15.

- ^ أ ب Steven Cherry, with Larry Constantine (14 December 2011). "Sons of Stuxnet". IEEE Spectrum.

- ^ Gary Samore speaking at the 10 December 2010 Washington Forum of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies in Washington DC, reported by C-Span and contained in the PBS program Need to Know ("Cracking the code: Defending against the superweapons of the 21st century cyberwar", 4 minutes into piece)

- ^ أ ب Sanger, David E. (1 June 2012). "Obama Order Sped Up Wave of Cyberattacks Against Iran". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ http://news.cnet.com/8301-17852_3-57478515-71/thunderstruck-a-tale-of-malware-ac-dc-and-irans-nukes/.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Iranian news agency reports another cyberattack by Stuxnet worm targeting industries in south". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ Krebs, Brian (17 July 2010). "Experts Warn of New Windows Shortcut Flaw". Krebs on Security. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س Gross, Michael Joseph (2011). "A Declaration of Cyber-War". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ أ ب "A worm in the centrifuge: An unusually sophisticated cyber-weapon is mysterious but important". The Economist. 30 September 2010.

- ^ Alexander Gostev (26 September 2010). "Myrtus and Guava: the epidemic, the trends, the numbers". Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ "W32.Stuxnet". Symantec. 17 September 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Michael Joseph Gross (2011). "A Declaration of Cyber-War". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ralph Langner (14 September 2010). "Ralph's Step-By-Step Guide to Get a Crack at Stuxnet Traffic and Behaviour". Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ Nicolas Falliere (26 September 2010). "Stuxnet Infection of Step 7 Projects". Symantec.

- ^ أ ب ت "W32.Stuxnet Dossier" (PDF). Symantec Corporation.

- ^ "SIMATIC WinCC / SIMATIC PCS 7: Information concerning Malware / Virus / Trojan". Siemens. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^ Tom Espiner (20 July 2010). "Siemens warns Stuxnet targets of password risk". cnet. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Repository of Industrial Security Incidents". Security Incidents Organization. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ "DHS National Cyber Security Division's CSSP". DHS. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Broad, William J.; Markoff, John; Sanger, David E. (15 January 2011). "Israel Tests on Worm Called Crucial in Iran Nuclear Delay". New York Times. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ "ISA99, Industrial Automation and Control System Security". International Society of Automation. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ "Industrial communication networks – Network and system security – Part 2-1: Establishing an industrial automation and control system security program". International Electrotechnical Commission. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ "Chemical Sector Cyber Security Program". ACC ChemITC. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ "Pipeline SCADA Security Standard" (PDF). API. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Marty Edwards (Idaho National Laboratory) & Todd Stauffer (Siemens). "2008 Automation Summit: A User's Conference"., United States Department of Homeland Security.

- ^ "The Can of Worms Is Open-Now What?". controlglobal.com. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ Byres, Eric and Cusimano, John (16 February 2012). "The 7 Steps to ICS Security". Tofino Security and exida Consulting LLC. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةwired - ^ أ ب ت Halliday, Josh (24 September 2010). "Stuxnet worm is the 'work of a national government agency'". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت Markoff, John (26 September 2010). "A Silent Attack, but Not a Subtle One". New York Times. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ Schneier, Bruce (6 October 2010). "The Story Behind The Stuxnet Virus". Forbes.

- ^ Schneier, Bruce (23 February 2012). "Another Piece of the Stuxnet Puzzle". Schneier on Security. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ^ Bright, Arthur (1 October 2010). "Clues Emerge About Genesis of Stuxnet Worm". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ Langner, Ralph (February 2011). "Ralph Langner: Cracking Stuxnet, a 21st-century cyber weapon".

- ^ Robert McMillan (23 July 2010). "Iran was prime target of SCADA worm". Computerworld. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ Paul Woodward (22 September 2010). "Iran confirms Stuxnet found at Bushehr nuclear power plant". Warincontext.org. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ "6 mysteries about Stuxnet". Blog.foreignpolicy.com. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ Clayton, Mark (21 September 2010). "Stuxnet malware is 'weapon' out to destroy ... Iran's Bushehr nuclear plant?". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ Yossi Melman (28 September 2010). "'Computer virus in Iran actually targeted larger nuclear facility'". Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ "Iranian Nuclear Program Plagued by Technical Difficulties". Globalsecuritynewswire.org. 23 November 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ "Iran pauses uranium enrichment at Natanz nuclear plant". Haaretz.com. 24 November 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ أ ب "The Stuxnet worm: A cyber-missile aimed at Iran?". The Economist. 24 September 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ "Serious nuclear accident may lay behind Iranian nuke chief%27s mystery resignation". wikileaks. 16 July 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ "IAEA Report on Iran" (PDF). Institute for Science and International Security. 16 November 2010. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Did Stuxnet Take Out 1,000 Centrifuges at the Natanz Enrichment Plant?" (PDF). Institute for Science and International Security. 22 December 2010. Retrieved 27 December 2010. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "ISIS" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ "Stuxnet-Virus könnte tausend Uran-Zentrifugen zerstört haben". Der Spiegel. 26 December 2010. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ^ Stark, Holger (8 August 2011). "Mossad's Miracle Weapon: Stuxnet Virus Opens New Era of Cyber War". Der Spiegel.

- ^ Warrick, Joby, "Iran's Natanz nuclear facility recovered quickly from Stuxnet cyberattack", Washington Post, 16 February 2011, retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ "Signs of sabotage in Tehran's nuclear programme". Gulf News. 14 July 2010.

- ^ أ ب Dan Williams (7 July 2009). "Wary of naked force, Israel eyes cyberwar on Iran". Reuters.

- ^ Aneja, Atul (26 September 2010). "Under cyber-attack, says Iran". Chennai, India: The Hindu.

- ^ "شبکه خبر :: راه های مقابله با ویروس"استاکس نت"" (in Iranian). Irinn.ir. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ أ ب "Stuxnet worm rampaging through Iran: IT official". AFP. Archived from the original on 28 September 2010.

- ^ "IRAN: Speculation on Israeli involvement in malware computer attack". Los Angeles Times. 27 September 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ أ ب Erdbrink, Thomas; Nakashima, Ellen (27 September 2010). "Iran struggling to contain 'foreign-made' 'Stuxnet' computer virus". Washington Post. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ "Ahmadinedschad räumt Virus-Attacke ein". Der Spiegel. 29 November 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ "Stuxnet: Ahmadinejad admits cyberweapon hit Iran nuclear program". The Christian Science Monitor. 30 November 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ أ ب Zetter, Kim (29 November 2010). "Iran: Computer Malware Sabotaged Uranium Centrifuges | Threat Level". Wired.com. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ "US Denies Role In Iranian Scientist's Death". Fox News. 7 April 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ Monica Amarelo (21 January 2011). "New FAS Report Demonstrates Iran Improved Enrichment in 2010". Federation of American Scientists.

- ^ "Report: Iran's nuclear capacity unharmed, contrary to U.S. assessment". Haaretz. 22 January 2011.

- ^ Jeffrey Goldberg (22 January 2011). "Report: Report: Iran's Nuclear Program Going Full Speed Ahead". The Atlantic.

- ^ "Experts say Iran has "neutralized" Stuxnet virus". Reuters. 14 February 2012.

- ^ Beaumont, Peter (30 September 2010). "Stuxnet worm heralds new era of global cyberwar". London: Guardian.co.uk.

- ^ Sanger, David E. (1 June 2012). "Obama Order Sped Up Wave of Cyberattacks Against Iran". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Hounshell, Blake (27 September 2010). "6 mysteries about Stuxnet". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ "Falkenrath Says Stuxnet Virus May Have Origin in Israel: Video. Bloomberg Television". 24 September 2010.

- ^ Williams, Dan. "Spymaster sees Israel as world cyberwar leader". Reuters. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ Dan Williams. "Cyber takes centre stage in Israel's war strategy". Reuters, 28 September 2010.

- ^ Antonin Gregoire. "Stuxnet, the real face of cyber warfare". Iloubnan.info, 25 November 2010.

- ^ أ ب Broad, William J.; Sanger, David E. (18 November 2010). "Worm in Iran Can Wreck Nuclear Centrifuges". The New York Times.

- ^ Williams, Christoper (16 February 2011). "Israeli security chief celebrates Stuxnet cyber attack". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ usccu.us

- ^ David Sanger (25 September 2010). "Iran Fights Malware Attacking Computers". New York Times. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ Iran/Critical National Infrastructure: Cyber Security Experts See The Hand Of Israel's Signals Intelligence Service In The "Stuxnet" Virus Which Has Infected Iranian Nuclear Facilities, 1 September 2010. [1].

- ^ Riddle, Warren (1 October 2010). "Mysterious 'Myrtus' Biblical Reference Spotted in Stuxnet Code". SWITCHED. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ "SCADA Systems Whitepaper" (PDF). Motorola.

- ^ "Symantec Puts 'Stuxnet' Malware Under the Knife". PC Magazine.

- ^ Zetter, Kim (1 October 2010). "New Clues Point to Israel as Author of Blockbuster Worm, Or Not". Wired.

- ^ أ ب Reals, Tucker (24 September 2010). "Stuxnet Worm a U.S. Cyber-Attack on Iran Nukes?". CBS News.

- ^ Halliday, Josh (18 January 2011). "WikiLeaks: US advised to sabotage Iran nuclear sites by German thinktank". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ Kim Zetter (17 February 2011). "Cyberwar Issues Likely to Be Addressed Only After a Catastrophe". Wired. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ Chris Carroll (18 October 2011). "Cone of silence surrounds U.S. cyberwarfare". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ John Bumgarner (27 April 2010). "Computers as Weapons of War" (PDF). IO Journal. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ Kroft, Steve (4 March 2012). "Stuxnet: Computer worm opens new era of warfare". 60 Minutes (CBS News). Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Iran blames U.S., Israel for Stuxnet malware" (SHTML). CBS News. 16 April 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Carr, Jeffrey (14 December 2010). "Stuxnet's Finnish-Chinese Connection". Forbes. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ Clayton, Mark (24 September 2010). "Stuxnet worm mystery: What's the cyber weapon after?". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ^ Gaycken, Sandro (26 November 2010). "Stuxnet: Wer war's? Und wozu?". Die ZEIT. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ Hopkins, Nick (31 May 2011). "UK developing cyber-weapons programme to counter cyber war threat". The Guardian (in الإنگليزية). المملكة المتحدة. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "The Global Intelligence Files - Re: [alpha] S3/G3* ISRAEL/IRAN - Barak hails munitions blast in Iran". Wikileaks. 14 November 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ^ "Duqu: A Stuxnet-like malware found in the wild, technical report" (PDF). Laboratory of Cryptography of Systems Security (CrySyS). 14 October 2011.

- ^ "Statement on Duqu's initial analysis". Laboratory of Cryptography of Systems Security (CrySyS). 21 October 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ "W32.Duqu – The precursor to the next Stuxnet (Version 1.2)" (PDF). Symantec. 20 October 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ Jim Finkle (28 December 2011). "Stuxnet weapon has at least 4 cousins: researchers". Reuters.

- ^ أ ب Zetter, Kim (28 May 2012). "Meet 'Flame,' The Massive Spy Malware Infiltrating Iranian Computers". Wired. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Resource 207: Kaspersky Lab Research Proves that Stuxnet and Flame Developers are Connected". Kaspersky Lab. 11 June 2012.

قراءات إضافية

- Langner, Ralph (2011). "Ralph Langner: Cracking Stuxnet, a 21st-century cyber weapon". TED. TED Conferences, LLC. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "The short path from cyber missiles to dirty digital bombs". Blog. Langner Communications GmbH. 26 December 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- Ralph Langner’s Stuxnet Deep Dive

- Falliere, Nicolas (21 September 2010). "Exploring Stuxnet's PLC Infection Process". Blogs: Security Response. Symantec. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- "Stuxnet Questions and Answers". News from the Lab. F-Secure. 1 October 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- Mills, Elinor (5 October 2010). "Stuxnet: Fact vs. theory". CNET News. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- Dang, Bruce; Ferrie, Peter (28 December 2010). "27C3: Adventures in analyzing Stuxnet". CCC-TV. Chaos Computer Club e.V. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- Russinovich, Mark (30 March 2011). "Analyzing a Stuxnet Infection with the Sysinternals Tools, Part 1". Mark's Blog. Microsoft Corporation. MSDN Blogs. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- Zetter, Kim (11 July 2011). "How Digital Detectives Deciphered Stuxnet, the Most Menacing Malware in History". Threat Level Blog. Condé Nast. Wired. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Kroft, Steve (4 March 2012). "Stuxnet: Computer worm opens new era of warfare". 60 Minutes (CBS News). Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Sanger, David E. (1 June 2012). "Obama Order Sped Up Wave of Cyberattacks Against Iran". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- CS1 errors: archive-url

- CS1 errors: missing title

- CS1 errors: bare URL

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة from December 2010

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة from July 2012

- برمجيات خبيثة

- روتکیت

- أمن الحاسوب

- Computer access control

- Privilege escalation exploits

- هجمات تعمية

- Exploit-based worms

- حوسبة صناعية

- البرنامج النووي الإيراني

- قتال الإنترنت

- 2010 في علوم الحاسوب

- نظريات المؤامرة

- 2010 في إيران

- العلاقات الأمريكية الإيرانية

- العلاقات الإسرائيلية الإيرانية