حمض نووي ريبوزي نقال

| tRNA | |

|---|---|

| المميزات | |

| الرمز | t |

| Rfam | RF00005 |

| بيانات أخرى | |

| RNA type | gene, tRNA |

| SO | {{{SO}}} |

| Available PDB structures | |

| 3icq, 1asy, 1asz, 1il2, 2tra, 3tra, 486d, 1fir, 1yfg, 3eph, 3epj, 3epk, 3epl, 1efw, 1c0a, 2ake, 2azx, 2dr2, 1f7u, 1f7v, 3foz, 2hgp, 2j00, 2j02, 2ow8, 2v46, 2v48, 2wdg, 2wdh, 2wdk, 2wdm, 2wh1 | |

الحمض النووي الريبوزي النقال إنگليزية: Transfer RNA or tRNA هو جزيء محول يتكون من الحمض النووي الريبوزي عادة طوله من 73 حتى 93 نوكليوتيد وهو بمثابة الرابط الفعلي بين تسلسل النوكليوتيدات الحمض النووي (الحمض النووي الريبوزي منقوص الأكسجين والحمض النووي الريبوزي) وتسلسل الأحماض الأمينية للبروتينات.

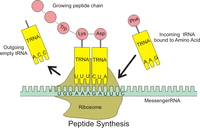

وظيفة الحمض النووي الريبوزي النقال tRNA هي قراءة كودون (ثلاث النيوكليوتيدات) الذي يحمل المرنا mRNA ، وإذا كان لديه الحمض الأميني المناسب للثلاثة (حسب الشفرة الجينيّة), فإنه يرتبط إلى الريبوسوم, حيث يتم إرفاقه بسلسلة البروتينات المبنية. بالتالي، الحمض النووي الريبوزي النقال tRNA يقف في مركز عملية الترجمة.

الحمض النووي الريبوزي النقال tRNA يشكل ما بين 10 ٪ و 15 ٪ من الحمض النووي الريبوزي RNA بخلايا البكتيريا. خلية بكتيريّة متوسطة تتضمن حوالي 400,000 من جزيئات الحمض النووي الريبوزي النقال tRNA.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

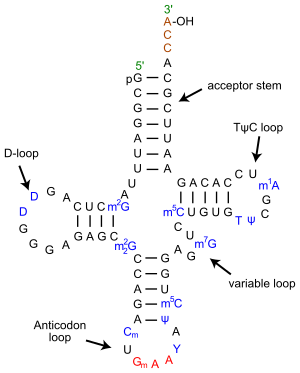

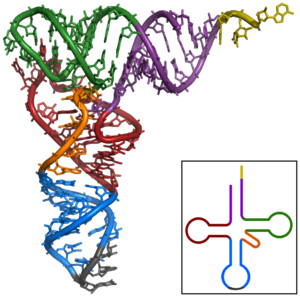

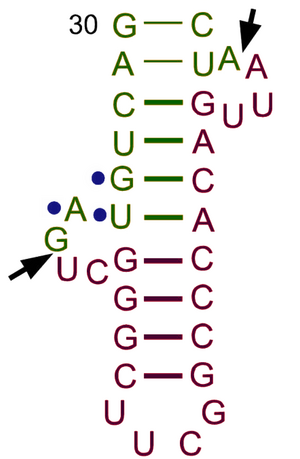

البنية

الارتباط بريبوسوم

التكون الحيوي للـ tRNA

In eukaryotic cells, tRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase III as pre-tRNAs in the nucleus.[3] RNA polymerase III recognizes two highly conserved downstream promoter sequences: the 5′ intragenic control region (5′-ICR, D-control region, or A box), and the 3′-ICR (T-control region or B box) inside tRNA genes.[4][5][6] The first promoter begins at +8 of mature tRNAs and the second promoter is located 30–60 nucleotides downstream of the first promoter. The transcription terminates after a stretch of four or more thymidines.[4][6]

Pre-tRNAs undergo extensive modifications inside the nucleus. Some pre-tRNAs contain introns that are spliced, or cut, to form the functional tRNA molecule;[7] in bacteria these self-splice, whereas in eukaryotes and archaea they are removed by tRNA-splicing endonucleases.[8] Eukaryotic pre-tRNA contains bulge-helix-bulge (BHB) structure motif that is important for recognition and precise splicing of tRNA intron by endonucleases.[9] This motif position and structure are evolutionarily conserved. However, some organisms, such as unicellular algae have a non-canonical position of BHB-motif as well as 5′- and 3′-ends of the spliced intron sequence.[9] The 5′ sequence is removed by RNase P,[10] whereas the 3′ end is removed by the tRNase Z enzyme.[11] A notable exception is in the archaeon Nanoarchaeum equitans, which does not possess an RNase P enzyme and has a promoter placed such that transcription starts at the 5′ end of the mature tRNA.[12] The non-templated 3′ CCA tail is added by a nucleotidyl transferase.[13] Before tRNAs are exported into the cytoplasm by Los1/Xpo-t,[14][15] tRNAs are aminoacylated.[16] The order of the processing events is not conserved. For example, in yeast, the splicing is not carried out in the nucleus but at the cytoplasmic side of mitochondrial membranes.[17]

Nonetheless, In March 2021, researchers reported evidence suggesting that a preliminary form of transfer RNA could have been a replicator molecule in the very early development of life, or abiogenesis.[18][19]

التاريخ

The existence of tRNA was first hypothesized by Francis Crick, based on the assumption that there must exist an adapter molecule capable of mediating the translation of the RNA alphabet into the protein alphabet. Paul C Zamecnik and Mahlon Hoagland discovered tRNA [20] Significant research on structure was conducted in the early 1960s by Alex Rich and Don Caspar, two researchers in Boston, the Jacques Fresco group in Princeton University and a United Kingdom group at King's College London.[21] In 1965, Robert W. Holley of Cornell University reported the primary structure and suggested three secondary structures.[22] tRNA was first crystallized in Madison, Wisconsin, by Robert M. Bock.[23] The cloverleaf structure was ascertained by several other studies in the following years[24] and was finally confirmed using X-ray crystallography studies in 1974. Two independent groups, Kim Sung-Hou working under Alexander Rich and a British group headed by Aaron Klug, published the same crystallography findings within a year.[25][26]

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ RNA %28tRNA%29 "Transfer RNA (tRNA)". Proteopedia.org. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Dunkle JA, Wang L, Feldman MB, Pulk A, Chen VB, Kapral GJ, Noeske J, Richardson JS, Blanchard SC, Cate JH (May 2011). "Structures of the bacterial ribosome in classical and hybrid states of tRNA binding". Science. 332 (6032): 981–984. Bibcode:2011Sci...332..981D. doi:10.1126/science.1202692. PMC 3176341. PMID 21596992.

- ^ White RJ (March 1997). "Regulation of RNA polymerases I and III by the retinoblastoma protein: a mechanism for growth control?". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 22 (3): 77–80. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(96)10067-0. PMID 9066256.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةsharp1985 - ^ Sharp S, Dingermann T, Söll D (September 1982). "The minimum intragenic sequences required for promotion of eukaryotic tRNA gene transcription". Nucleic Acids Research. 10 (18): 5393–5406. doi:10.1093/nar/10.18.5393. PMC 320884. PMID 6924209.

- ^ أ ب Dieci G, Fiorino G, Castelnuovo M, Teichmann M, Pagano A (December 2007). "The expanding RNA polymerase III transcriptome". Trends in Genetics. 23 (12): 614–622. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2007.09.001. hdl:11381/1706964. PMID 17977614.

- ^ Tocchini-Valentini GD, Fruscoloni P, Tocchini-Valentini GP (December 2009). "Processing of multiple-intron-containing pretRNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (48): 20246–20251. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10620246T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0911658106. PMC 2787110. PMID 19910528.

- ^ Abelson J, Trotta CR, Li H (May 1998). "tRNA splicing". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (21): 12685–12688. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.21.12685. PMID 9582290.

- ^ أ ب Soma A (2014). "Circularly permuted tRNA genes: their expression and implications for their physiological relevance and development". Frontiers in Genetics. 5: 63. doi:10.3389/fgene.2014.00063. PMC 3978253. PMID 24744771.

- ^ Frank DN, Pace NR (1998). "Ribonuclease P: unity and diversity in a tRNA processing ribozyme". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 67 (1): 153–180. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.153. PMID 9759486.

- ^ Ceballos M, Vioque A (2007). "tRNase Z". Protein and Peptide Letters. 14 (2): 137–145. doi:10.2174/092986607779816050. PMID 17305600.

- ^ Randau L, Schröder I, Söll D (May 2008). "Life without RNase P". Nature. 453 (7191): 120–123. Bibcode:2008Natur.453..120R. doi:10.1038/nature06833. PMID 18451863. S2CID 3103527.

- ^ Weiner AM (October 2004). "tRNA maturation: RNA polymerization without a nucleic acid template". Current Biology. 14 (20): R883-5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.069. PMID 15498478.

- ^ Kutay U, Lipowsky G, Izaurralde E, Bischoff FR, Schwarzmaier P, Hartmann E, Görlich D (February 1998). "Identification of a tRNA-specific nuclear export receptor". Molecular Cell. 1 (3): 359–369. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80036-2. PMID 9660920.

- ^ Arts GJ, Fornerod M, Mattaj IW (March 1998). "Identification of a nuclear export receptor for tRNA". Current Biology. 8 (6): 305–314. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70130-7. PMID 9512417. S2CID 17803674.

- ^ Arts GJ, Kuersten S, Romby P, Ehresmann B, Mattaj IW (December 1998). "The role of exportin-t in selective nuclear export of mature tRNAs". The EMBO Journal. 17 (24): 7430–7441. doi:10.1093/emboj/17.24.7430. PMC 1171087. PMID 9857198.

- ^ Yoshihisa T, Yunoki-Esaki K, Ohshima C, Tanaka N, Endo T (August 2003). "Possibility of cytoplasmic pre-tRNA splicing: the yeast tRNA splicing endonuclease mainly localizes on the mitochondria". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 14 (8): 3266–3279. doi:10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0757. PMC 181566. PMID 12925762.

- ^ Kühnlein, Alexandra; Lanzmich, Simon A.; Brun, Dieter (2 March 2021). "tRNA sequences can assemble into a replicator". eLife. 10. doi:10.7554/eLife.63431. PMC 7924937. PMID 33648631.

- ^ Maximilian, Ludwig (3 April 2021). "Solving the Chicken-and-the-Egg Problem – "A Step Closer to the Reconstruction of the Origin of Life"". SciTechDaily. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Kresge, Nicole; Simoni, Robert D.; Hill, Robert L. (October 7, 2005). "The Discovery of tRNA by Paul C. Zamecnik". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (40): e37–e39. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(20)79029-0 – via www.jbc.org.

- ^ Clark BF (October 2006). "The crystal structure of tRNA" (PDF). Journal of Biosciences. 31 (4): 453–457. doi:10.1007/BF02705184. PMID 17206065. S2CID 19558731.

- ^ Holley RW, Apgar J, Everett GA, Madison JT, Marquisee M, Merrill SH, Penswick JR, Zamir A (March 1965). "Structure of a Ribonucleic Acid". Science. 147 (3664): 1462–1465. Bibcode:1965Sci...147.1462H. doi:10.1126/science.147.3664.1462. PMID 14263761. S2CID 40989800.

- ^ "Obituary". The New York Times. July 4, 1991.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1968". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2007-07-28.

- ^ Ladner JE, Jack A, Robertus JD, Brown RS, Rhodes D, Clark BF, Klug A (November 1975). "Structure of yeast phenylalanine transfer RNA at 2.5 A resolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 72 (11): 4414–4418. Bibcode:1975PNAS...72.4414L. doi:10.1073/pnas.72.11.4414. PMC 388732. PMID 1105583.

- ^ Kim SH, Quigley GJ, Suddath FL, McPherson A, Sneden D, Kim JJ, Weinzierl J, Rich A (January 1973). "Three-dimensional structure of yeast phenylalanine transfer RNA: folding of the polynucleotide chain". Science. 179 (4070): 285–288. Bibcode:1973Sci...179..285K. doi:10.1126/science.179.4070.285. PMID 4566654. S2CID 28916938.