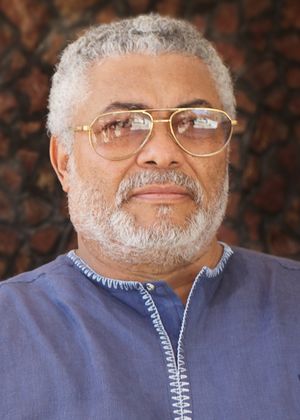

جري رولنگز

جري رولنگز Jerry John Rawlings | |

|---|---|

| |

| رئيس غانا | |

| في المنصب 7 يناير 1993 – 7 يناير 2001 | |

| نائب الرئيس | كو نكينسن أركاه جون أتا ميلز |

| سبقه | Himself (as head of state) |

| خلـَفه | جون كوفور |

| Head of State of Ghana Chairman of the Provisional National Defence Council | |

| في المنصب 31 ديسمبر 1981 – 7 يناير 1993 | |

| سبقه | Hilla Limann |

| رئيس دولة غانا رئيس المجلس الثوري للقوات المسلحة | |

| في المنصب 4 يونيو 1979 – 24 سبتمبر 1979 | |

| سبقه | الجنرال فريد أكوفو |

| خلـَفه | هيلا ليمان |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | Jerry Rawlings John 22 يونيو 1947 أكرا ، جولد كوست (الآن غانا) |

| توفي | 12 نوفمبر 2020 (aged 73) أكرا ، غانا |

| الحزب | المؤتمر الوطني الديمقراطي (بعد عام 1992) |

| الزوج | |

| الأنجال | 4 |

| المهنة | طيار مقاتل |

| الجوائز | جائزة UDS الفخرية |

| الخدمة العسكرية | |

| الولاء | |

| الفرع/الخدمة | القوات الجوية الغانية |

| سنوات الخدمة | 1968–92 |

| الرتبة | ملازم طيران |

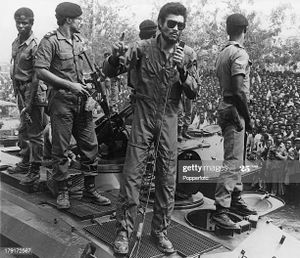

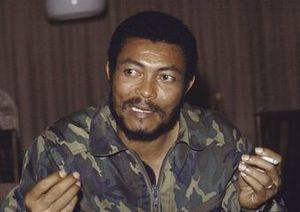

جري رولنگز (22 يونيو 1947 - 12 نوفمبر 2020)[1] كان ضابطًا عسكريًا وسياسيًا غانيًا قاد البلاد من 1981 إلى 2001 وأيضًا لفترة وجيزة في 1979. قاد المجلس العسكري حتى عام 1992 ، ثم خدم فترتين كرئيس منتخب ديمقراطيا لغانا.[2][3][4]

جاء إلى السلطة في البداية في غانا كملازم طيران في سلاح الجو الغاني بعد انقلاب عام 1979. وقبل ذلك ، قاد محاولة انقلاب فاشلة ضد الحكومة العسكرية الحاكمة في 15 مايو 1979 ، قبل خمسة أسابيع فقط من الموعد المقرر كان من المقرر إجراء انتخابات ديمقراطية. بعد تسليم السلطة في البداية إلى حكومة مدنية ، استعاد السيطرة على البلاد في 31 ديسمبر 1981 كرئيس لمجلس الدفاع الوطني المؤقت (PNDC). في عام 1992 ، استقال رولينگز من الجيش ، وأسس المؤتمر الوطني الديمقراطي (NDC) ، وأصبح أول رئيس للجمهورية الرابعة.[5] أعيد انتخابه في عام 1996 لمدة أربع سنوات أخرى. بعد فترتين في المنصب ، وهو الحد الأقصى وفقًا للدستور الغاني ، أيد رولنگز نائب الرئيس جون أتا ميلز كمرشح رئاسي في عام 2000. وعمل رولنگز مبعوثًا للاتحاد الأفريقي إلى الصومال.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الخلفية

ولد في 22 يونيو 1947 في أكرا ، غانا ، والده فيكتوريا أگبوتوي ، من دزيلوكوب وكيتا وجيمس رامسي جون ، وهو كيميائي من قلعة دوجلاس في كيركودبرايتشاير ، اسكتلندا. يعيش أحفاد جيمس رامزي جون الآن في نيوكاسل ولندن. التحق بمدرسة أشيموتا والأكاديمية العسكرية في تيشي.[4][6] كان متزوجًا من نانا كونادو أجيمان ، التي التقى بها أثناء وجوده في كلية أشيموتا. لديهم ثلاث بنات: زانيتور رولينگز ، يا أسانتيوا رولينگز ، أمينة رولينگز ؛ وابن واحد ، كيماثي رولينگز[7][8]

التعليم والسيرة العسكرية

أنهى رولينگز تعليمه الثانوي في كلية أشيموتا في عام 1967.[9] انضم إلى القوات الجوية الغانية بعد ذلك بوقت قصير ؛ بناء على طلبه ، قام الجيش بتغيير لقبه جون واسمه الأوسط رولينگز. في مارس 1968 ، تم إرساله إلى تاكورادي ، في المنطقة الغربية بغانا ، لمواصلة دراسته.[10] تخرج في يناير 1969 ، وتم تكليفه كضابط طيار ، وفاز بجائزة "Speed Bird Trophy" كأفضل طالب في طيران Su-7 طائرة نفاثة الأسرع من الصوت للهجوم الأرضي حيث كان ماهرًا في الأكروبات. حصل على رتبة ملازم طيار وفي أبريل 1978. أثناء خدمته في سلاح الجو الغاني ، لاحظ رولنگز تدهورًا في الانضباط والروح المعنوية بسبب الفساد في المجلس العسكري الأعلى (SMC). عندما جعله الترويج على اتصال مع الطبقات المتميزة وقيمها الاجتماعية ، تشددت نظرته للظلم في المجتمع. وبالتالي ، كان ينظر إليه ببعض القلق من قبل مجمع السليمانية الطبي. بعد انقلاب عام 1979 ، شارك في المجتمع الطلابي في جامعة غانا ، حيث طور أيديولوجية أكثر يسارية من خلال قراءة ومناقشة الأفكار الاجتماعية والسياسية. [11]

انقلاب 1979 وتطهيراته

ازداد استياء رولنگز من حكومة إگناتيوس كوتو أتشيامپونگ ، التي وصلت إلى السلطة من خلال انقلاب في يناير 1972. [6] اتهم أتشيامپونگ ليس فقط بالفساد ، ولكن أيضًا بالحفاظ على اعتماد غانا على قوى ما قبل الاستعمار التي أدت إلى التدهور الاقتصادي والفقر. [6]

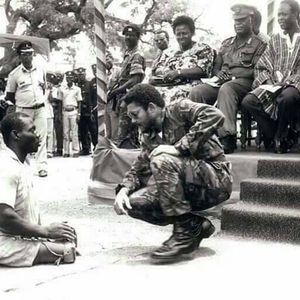

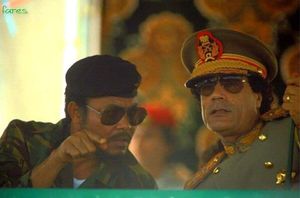

كان رولنگز جزءًا من حركة إفريقيا الحرة ، وهي حركة سرية لضباط الجيش الذين أرادوا توحيد إفريقيا من خلال سلسلة من الانقلابات. في 15 مايو 1979 ، قبل خمسة أسابيع من الانتخابات المدنية ، قام رولنگز وستة جنود آخرين بانقلاب ضد حكومة الجنرال فريد أكوفو ، لكنهم فشلوا واعتقلهم الجيش الغاني.[12] حُكم على رولنگز بالإعدام علنًا في محكمة عسكرية عامة وسجن ، على الرغم من أن تصريحاته حول المظالم الاجتماعية التي حفزت أفعاله أكسبته تعاطفًا مدنيًا.[12] أثناء انتظار الإعدام ، خرج رولنگز من الحجز في 4 يونيو 1979 من قبل مجموعة من الجنود. بزعم أن الحكومة كانت فاسدة بشكل لا يمكن استرداده وأن القيادة الجديدة كانت مطلوبة لتنمية غانا ، فقد قاد المجموعة في انقلاب للإطاحة بحكومة أكوفو والمجلس العسكري الأعلى.[13] بعد ذلك بوقت قصير ، أسس رولنگز وأصبح رئيسًا للمجلس الثوري للقوات المسلحة المكون من 15 عضوًا ، ويتألف بشكل أساسي من صغار الضباط.[14][9] حكم هو والمجلس الثوري للقوات المسلحة لمدة 112 يومًا ورتبوا الإعدام رمياً بالرصاص من خلال فرقة مكونة من ثمانية ضباط عسكريين ، بما في ذلك الجنرالات كوتاي وجوي أميدوم وروجر فيلي وأوتوكا ، فضلاً عن الرؤساء الثلاثة السابقين للدول: أفريفا وأتشيامپونگ وأكوفو.[6][4]

كانت عمليات الإعدام أحداثاً مأساوية في تاريخ غانا ، التي عانت من حالات قليلة من العنف السياسي. نفذ رولنگز في وقت لاحق "تمرين تنظيف المنزل" على نطاق أوسع يتضمن قتل واختطاف أكثر من 300 غاني. أجريت الانتخابات في موعدها بعد فترة وجيزة من الانقلاب. في 24 سبتمبر 1979 ، سلم رولنگز السلطة بسلام إلى الرئيسة هيلا ليمان ، الذي حظي حزبها الوطني الشعبي (PNP) بدعم أتباع نكروما.[14] بعد ذلك بعامين ، أطاح رولنگز بالرئيسة هيلا ليمان في انقلاب في 31 ديسمبر 1981 ، مدعيا أن الحكم المدني كان ضعيفا وأن اقتصاد البلاد آخذ في التدهور. كما وقعت عمليات قتل قضاة المحكمة العليا (سيسيليا كورانتنگ-أدو ، وفريدريك ساركودي ، وكوادجو أجي أجييبونگ) وضباط الجيش الرائد سام أكوا والرائد داسانا نانتوگماه خلال الحكم العسكري الثاني لرولنگز. ومع ذلك ، على عكس عمليات الإعدام عام 1979 ، تم اختطاف هؤلاء الأشخاص وقتلهم سراً ومن غير الواضح من كان وراء جرائم القتل ، على الرغم من أن يواكيم أمارتي كويي وأربعة آخرين أدينوا بأربع من جرائم القتل هذه ، والتي شملت جميع القضاة الثلاثة وأكوا أُعدم عام 1982. [15]

انقلاب 1981 واصلاحاته

معتقدًا أن نظام ليمان غير قادر على حل التبعية الاقتصادية الاستعمارية لغانا ، قاد رولنگز انقلابًا ثانيًا ضد ليمان واتهم الطبقة السياسية بأكملها في 31 ديسمبر 1981. [16] بدلاً من الحزب الوطني الشعبي ، أنشأ رولنگز المجلس العسكري المؤقت لمجلس الدفاع الوطني (PNDC) باعتباره الحكومة الرسمية. [16]

على الرغم من ادعاء المجلس الوطني الفلسطيني للدفاع عن حقوق الإنسان أنه ممثل للشعب ، إلا أنه يفتقر إلى الخبرة في إنشاء وتنفيذ سياسات اقتصادية واضحة.[6] عزا رولنگز ، مثل العديد من أسلافه ، المشاكل الاقتصادية والاجتماعية الحالية إلى "الممارسات التجارية السيئة وغيرها من الأنشطة المعادية للمجتمع" لعدد قليل من رجال الأعمال.[17] في ديسمبر 1982 ، أعلن المجلس الوطني الفلسطيني لمكافحة الفساد عن برنامجه الاقتصادي الذي يمتد لأربع سنوات لإنشاء احتكار الدولة لتجارة الصادرات والواردات بهدف القضاء على الفساد المحيط بتراخيص الاستيراد وتحويل التجارة بعيدًا عن التبعية للأسواق الغربية.[17] تم فرض ضوابط غير واقعية على الأسعار في السوق وفرضت من خلال أعمال قسرية ، وخاصة ضد رجال الأعمال.[6] يتضح هذا التصميم على استخدام سيطرة الدولة على الاقتصاد من خلال تدمير سوق ماكولا رقم 1.[17] أنشأ المجلس الوطني الفلسطيني للدفاع عن العمال لجان الدفاع العمالية (WDCs) ولجان الدفاع الشعبية (PDC) لتعبئة السكان لدعم تغييرات جذرية في الاقتصاد.[17] أدت سياسات رولنگز الاقتصادية إلى أزمة اقتصادية في عام 1983 ، مما أجبره على إجراء تعديل هيكلي والخضوع للانتخابات للاحتفاظ بالسلطة.[18] أجريت الانتخابات في يناير 1992 ، مما أدى إلى عودة غانا إلى الديمقراطية التعددية.[16]

انتخابات 1992

أنشأ رولنگز اللجنة الوطنية للديمقراطية (NCD) بعد وقت قصير من انقلاب عام 1982 ، واستخدمها لاستطلاع آراء المدنيين وتقديم توصيات من شأنها تسهيل عملية التحول الديمقراطي. في مارس 1991 ، أصدرت NCD تقريرًا يوصي بانتخاب رئيس تنفيذي ، وإنشاء جمعية وطنية ، وإنشاء منصب رئيس الوزراء. استخدم المجلس الوطني الفلسطيني لمكافحة الإرهاب توصيات NCD لإنشاء لجنة لصياغة دستور جديد على أساس الدساتير الغانية السابقة ، والتي رفعت الحظر المفروض على الأحزاب السياسية في مايو 1992 بعد الموافقة عليه عن طريق الاستفتاء.[16]

On 3 November 1992, election results compiled by the INEC from 200 constituencies showed that Rawlings' NDC had won 60% of the votes, and had obtained the majority needed to prevent a second round of voting.[16] More specifically, the NDC won 62% in the Brong-Ahafo region, 93% in the Volta region, and majority votes in Upper West, Upper East, Western, Northern, Central, and Greater Accra regions.[16] His opponents Professor Adu Boahen won 31% of the votes, former President Hilla Limann won 6.8%, Kwabena Darko won 2.9%, and Emmanuel Erskine won 1.7%.[16] Voter turnout was 50%.[19]

The ability of opposition parties to compete was limited by the vast advantages Rawlings possessed. Rawlings' victory was aided by the various party structures that were integrated into society during his rule, called the "organs of the revolution".[16] These structures included the Committees for the Defence of the Revolution (CDRs), Commando Units, the 31st December Women's Organization, the 4 June movement, Peoples Militias, and Mobisquads, and operated on a system of popular control through intimidation.[16] He had a monopoly over national media, and was able to censor print and electronic media through a PNDC newspaper licensing decree, PNDC Law 221.[16] Moreover, Rawlings imposed a 20,000 cedis (about $400) cap on campaign contributions, which made national publicity of opposition parties virtually impossible. Rawlings himself began campaigning before the official unbanning of political parties and had access to state resources and was able to effectively meet all monetary demands required of a successful campaign.[19][16] Rawlings travelled across the country, initiating public-works projects and giving public employees a 60% pay rise prior to election day.[19]

Opposition parties objected to the election results, citing incidences of vote stuffing in regions Rawlings where was likely to lose and rural areas with scant populations, as well as a bloated voters' register and a partisan electoral commission.[16][19] However, the Commonwealth Observer Group, led by Sir Ellis Clarke, approved of the election as "free and fair", as there very few issues at polling stations and no major incidences of voter coercion.[16] In contrast, the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) issued a report supporting claims that erroneous entries in voter registration could have affected election results.[16] The Carter Center did acknowledge minor electoral issues but did not see these problems as indicative of systematic electoral fraud.[19]

Opposition parties boycotted subsequent Ghana Parliamentary and Presidential elections, and the unicameral National Assembly, of which NDC officials won 189 of 200 seats and essentially established a one-party parliament that lacked legitimacy and only had limited legislative powers.[19] After the disputed election, the PNDC was transformed into the National Democratic Congress (NDC).[20]

Rawlings took office on 7 January 1993, the same day that the new constitution came into effect, and the government became known as the Fourth Republic of Ghana.[21]

السياسات والإصلاحات

Rawlings established the Economic Recovery Program (ERP) suggested by the World Bank and the IMF in 1982 due to the poor state of the economy after 18 months of attempting to govern it through administrative controls and mass mobilization.[19] The policies implemented caused a dramatic currency devaluation, the removal of price controls and social-service subsidies that favored farmers over urban workers, and privatization of some state-owned enterprises, and restraints on government spending.[19] Funding was provided by bilateral donors, reaching $800 million in 1987 and 1988, and $US900 million in 1989.[19]

Between 1992 and 1996, Rawlings eased control over the judiciary and civil society, allowing a more independent Supreme Court and the publication of independent newspapers. Opposition parties operated outside of parliament and held rallies and press conferences.[19]

انتخابات 1996

Given the various issues with the 1992 elections, the 1996 elections were a great improvement in terms of electoral oversight. Voter registration was re-compiled, with close to 9.2 million voters registering at nearly 19,000 polling stations, which the opposition had largely approved after party agents had reviewed the lists.[19] The emphasis on transparency led Ghanaian non-governmental organizations to create the Network of Domestic Election Observers (NEDEO), which trained nearly 4,100 local poll-watchers.[19] This organization was popular across political parties and civic groups. On the day of the election, more than 60,000 candidate agents monitored close to all polling sites, and were responsible for directly reporting results to their respective party leader.[19] The parallel vote-tabulation system allowed polling sites to compare their results to the official ones released by the Electoral commission.[19] The Inter-Party Advisory Committee (IPAC) was established to discuss election preparations with all parties and the Electoral Commission, as well as establish procedures to investigate and resolve complaints.[19][22] Presidential and parliamentary elections were held on the same day and see-through boxes were used in order to further ensure the legitimacy of the elections.[19] Despite some fears of electoral violence, the election was peaceful and had a 78% turnout rate, and was successful with only minor problems such as an inadequate supply of ink and parliamentary ballots.[19]

The two major contenders of the 1996 election were Rawlings' NDC, and John Kufuor's Great Alliance, an amalgamation of the New Patriotic Party (NPP) and the People's Convention Party (PCP).[19] The Great Alliance based their platform on ousting Rawlings, and attacked the incumbent government for its poor fiscal policies. However, they were unable to articulate a clear positive message of their own, or plans to change the current economic policy. As Ghana was heavily dependent on international aid, local leaders had minimal impact on the economy. The Electoral Commission reported that Rawlings had won by 57%, with Kufuor obtaining 40% of the vote. Results by district were similar to those in 1992, with the opposition winning the Ashanti Region and some constituencies in Eastern and Greater Accra, and Rawlings winning in his ethnic home, the Volta, and faring well in every other region.[19] The NDC took 134 seats in the Assembly compared to the opposition's 66, and the NPP took 60 seats in the parliament.[23][24]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

بعد الحياة العسكرية

وفقًا لولايته الدستورية ، انتهت فترة رولينگز في المنصب في عام 2001. تقاعد في عام 2001 وخلفه جون أجيكوم كوفور ،[25]منافسه الرئيسي وخصمه عام 1996.

نجح كوفور في هزيمة نائب رئيس رولينگز جون أتا ميلز في 2000. في عام 2004 ، تنازل ميلز لكوفور لمدة أربع سنوات أخرى.[26]

بعد الرئاسة

In November 2000, Rawlings was named the first International Year of Volunteers 2001 Eminent Person by UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, attending various events and conferences to promote volunteerism. He established the constitution of 1988[27]

In October 2010, Rawlings was named African Union envoy to Somalia.[28]

He gave lectures at universities, including Oxford University.[29] Rawlings continued his heavy support for NDC.[30] In July 2019, he went on a three-day working trip to Burkina Faso in the capacity of Chairman of the Thomas Sankara Memorial Committee.[31]

In September 2019, he paid a tribute on behalf of the president and people of Ghana, when he led a delegation to the funeral of Robert Mugabe, the late former president of Zimbabwe.[32][33]

الوفاة

توفي رولينگز في 12 نوفمبر 2020 في مستشفى كورلي بو التعليمي في أكرا ، بعد أسبوع من قبوله بسبب مرض لم يتم الكشف عنه.[34][35]وجاءت وفاته بعد شهرين من وفاة والدته فيكتوريا أگبوتوي في 24 سبتمبر 2020.[36]

الجوائز والتكريمات

- October 2013: Honorary degree (Doctorate of Letters) from the University for Development Studies in northern Ghana.

This award recognised Rawlings's contribution to the establishment of the University. In 1993, he used his US$50,000 Hunger Project cash prize as seed money to sponsor the establishment of the state-owned university (founded in May 1992), the first of its kind in the three northern regions.[37] - October 2013: Global Champion for People's Freedom award by the Mkiva Humanitarian Foundation.[38]

الهامش

- ^ "FLT LT JERRY JOHN RAWLINGS Former President of The Republic of Ghana". Archived from the original on 27 ديسمبر 2012. Retrieved 3 يناير 2013.

- ^ "Ghana : History | The Commonwealth". thecommonwealth.org. Archived from the original on 7 مايو 2019. Retrieved 22 مايو 2019.

- ^ "Rawlings hails frontline health workers". MyJoyOnline.com (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 4 يونيو 2020. Archived from the original on 5 يونيو 2020. Retrieved 5 يونيو 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت "Jerry J. Rawlings | head of state, Ghana". Encyclopedia Britannica (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 3 أغسطس 2020.

- ^ "Flt.-Lt. (Rtd) Jerry John Rawlings Profile". Archived from the original on 14 فبراير 2013. Retrieved 3 يناير 2013.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Nugent, Paul (2009). "Nkrumah and Rawlings: Political Lives in Parallel?". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana (12): 35–56. JSTOR 41406753.

- ^ Gracia, Zindzy (1 فبراير 2018). "Jj Rawlings' Family". Yen.com.gh - Ghana news. (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 2 أغسطس 2019. Retrieved 2 أغسطس 2019.

- ^ MyNewsGH (28 نوفمبر 2018). "All my CHILDREN are POLITICIANS- Konadu RAWLINGS makes shocking disclosure". MyNewsGh (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 26 مايو 2020.

- ^ أ ب Morrison, Minion K. C. (2004). "Political Parties in Ghana through Four Republics: A Path to Democratic Consolidation". Comparative Politics. 36 (4): 421–442. doi:10.2307/4150169. JSTOR 4150169.

- ^ "Rawlings recounts how the military changed his 'real surname'". Adom Online. 13 يوليو 2020. Retrieved 8 سبتمبر 2020.

- ^ "Biography of the Former President of the Republic of Ghana, FLT Lt Jerry John Rawlings". Archived from the original on 27 ديسمبر 2012. Retrieved 3 يناير 2013.

- ^ أ ب "May 15, 1979: Flt. Lt. Jerry Rawlings arrested after failed military uprising". Edward A. Ulzen Memorial Foundation (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on 25 نوفمبر 2018. Retrieved 24 نوفمبر 2018.

- ^ Pike, John. "Ghana - Rawlings Coup". www.globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 29 نوفمبر 2018. Retrieved 28 نوفمبر 2018.

- ^ أ ب Adedeji, John (Summer 2001). "The Legacy of J.J. Rawlings in Ghanaian Politics 1979-2000" (PDF). African Studies Quarterly. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 فبراير 2019. Retrieved 25 نوفمبر 2018.

- ^ Schabas, William A.; Darcy, Shane (18 فبراير 2005). Truth Commission and Courts: The Tension Between Criminal Justice and the Search for Truth. Springer. p. 128. ISBN 9781402032233. Retrieved 22 مارس 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص Abdulai, David (1992). "Rawlings "Wins" Ghana's Presidential Elections: Establishing a New Constitutional Order". Africa Today. 39 (4): 66–71. JSTOR 4186868.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "The Politics of Reform in Ghana, 1982–1991". publishing.cdlib.org (in الإنجليزية). University of California Press. Archived from the original on 25 نوفمبر 2018. Retrieved 24 نوفمبر 2018.

- ^ Horton, Richard (22 ديسمبر 2001). "Ghana: defining the African challenge". The Lancet (in الإنجليزية). 358 (9299): 2141–2149. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07221-X. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 11784645.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ Lyons, Terrence (1 أبريل 1997). "A Major Step Forward". Journal of Democracy (in الإنجليزية). 8 (2): 65–77. doi:10.1353/jod.1997.0019. ISSN 1086-3214.

- ^ Adedeji, John (Summer 2001). "The Legacy of J.J. Rawlings in Ghanaian Politics 1979-2000" (PDF). African Studies Quarterly. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 فبراير 2019. Retrieved 25 نوفمبر 2018.

- ^ "Ghana: Update on the Fourth Republic". Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. 1 سبتمبر 1994. Retrieved 5 يناير 2020 – via UNHCR.

- ^ "The Electoral Political Process". Devex (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 30 نوفمبر 2012. Archived from the original on 26 نوفمبر 2018. Retrieved 24 نوفمبر 2018.

- ^ "GHANA: parliamentary elections Parliament, 1996". archive.ipu.org. Retrieved 25 مايو 2020.

- ^ Peace FM. "Ghana Election 1996". Ghana Elections - Peace FM. Archived from the original on 2 أغسطس 2019. Retrieved 2 أغسطس 2019.

- ^ "Rawlings Attacks Kufuor". Modern Ghana (in الإنجليزية). 1 أكتوبر 2002. Archived from the original on 2 أغسطس 2019. Retrieved 2 أغسطس 2019.

- ^ Duodu, Cameron (8 أغسطس 2012). "John Atta Mills: Politician who helped secure democracy in Ghana". The Independent (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 2 أغسطس 2019. Retrieved 2 أغسطس 2019.

- ^ "IYV 2001: A chronology" published at unv.org Archived 6 أكتوبر 2016 at the Wayback Machine, by UN Volunteers. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ "Rawlings named AU envoy to Somalia", 9 October 2010. Archived 2 يونيو 2011 at the Wayback Machine. news24.com.

- ^ Kasuka, Bridgette (أبريل 2013). Prominent African Leaders Since Independence (in الإنجليزية). New Africa Press. ISBN 978-9987-16-026-6.

- ^ Akosah-Sarpong, Kofi, "Jerry Rawlings: A Threat to Ghana's Democracy?" Archived 7 يناير 2015 at the Wayback Machine. The African Executive.

- ^ "Archived copy". www.graphic.com.gh. Archived from the original on 18 يوليو 2019. Retrieved 18 يوليو 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Mugabe was a 'formidable warrior' - Rawlings' tribute on behalf of gov't". www.myjoyonline.com. Archived from the original on 17 سبتمبر 2019. Retrieved 14 سبتمبر 2019.

- ^ "Archived copy". www.graphic.com.gh. Archived from the original on 18 سبتمبر 2019. Retrieved 16 سبتمبر 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Breaking News: Jerry John Rawlings is dead". ghanaweb.com. Ghana Web. 12 نوفمبر 2020. Retrieved 12 نوفمبر 2020.

- ^ Akorlie, Christian (12 نوفمبر 2020). "Jerry Rawlings, Ghana's unlikely democrat, dies at 73". Reuters.

- ^ "Rawlings' mother has died – MyJoyOnline.com". www.myjoyonline.com. 24 سبتمبر 2020. Retrieved 12 نوفمبر 2020.

- ^ University for Development Studies News. "Acceptance Speech by H. E. Jerry John Rawlings" (PDF). Leadership for Sustainable Development and Democratic Transition in Ghana. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 أكتوبر 2013. Retrieved 27 أكتوبر 2013.

- ^ Peace FM Online (27 أكتوبر 2013). "Rawlings Receives Another Award In South Africa And Says The World Is Engulfed In Hypocrisy". Office of Flt. Lt. Jerry John Rawlings/Former President of the Republic of Ghana. Archived from the original on 29 أكتوبر 2013. Retrieved 27 أكتوبر 2013.

وصلات خارجية

للاستزادة

Danso-Boafo, Kwaku. J. J. Rawlings and the democratic transition in Ghana. Accra: Ghana Universities Press, 2012.

| مناصب سياسية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه Fred Akuffo |

Head of state of Ghana 1979 |

تبعه Hilla Limann |

| سبقه Hilla Limann |

Head of state of Ghana 1981–1993 |

تبعه Constitutional Rule |

| سبقه Constitutional rule re-established in Ghana |

President of Ghana 1993 – 2001 |

تبعه John Kufuor |

| سبقه Nicéphore Soglo |

Chairman of the Economic Community of West African States 1994 – 1996 |

تبعه Sani Abacha |

| مناصب عسكرية | ||

| سبقه Joseph Nunoo-Mensah |

Chief of the Defence Staff November 1982 — August 1983 |

تبعه Arnold Quainoo |

| مناصب حزبية | ||

| لقب حديث | National Democratic Congress presidential candidate 1992, 1996 |

تبعه John Atta Mills |

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Use dmy dates from October 2013

- مواليد 1947

- وفيات 2020

- خريجو مدرسة أشيموتا

- رؤساء أركان الدفاع (غانا)

- أفراد القوات الجوية الغانية

- الروم الكاثوليك الغانيين

- الغانيون من أصل اسكتلندي

- الجنود الغانيون

- زعماء استولوا على السلطة بإنقلاب

- سياسيو المؤتمر الوطني الديمقراطي (غانا)

- أشخاص من أكرا

- رؤساء غانا