خربة البرج (تل دور)

تل دور من أعلى | |

| الاسم البديل | Tell el-Burj, Khirbet el-Burj (Arabic) |

|---|---|

| المكان | منطقة حيفا، إسرائيل |

| المنطقة | المشرق |

| الإحداثيات | 32°37′03″N 34°55′03″E / 32.61750°N 34.91750°E |

| النوع | مستوطنة |

| التاريخ | |

| هـُـجـِر | 630s |

| ملاحظات حول الموقع | |

| الحالة | In ruins |

تل دور ( Tel Dor ؛ بالعبرية: דוֹר or דאר, meaning "generation", "habitation") أو تل البرج، وأيضاً خربة البرج، هي موقع أثري في السهل الساحلي الإسرائيلي المطل على البحر المتوسط بجانب قرية الطنطورة المهجرة وموشاڤ دور، على بعد نحو 30 كم جنوب حيفا، و 2.5 كم غرب Hadera. Lying on a small headland at the north side of a protected inlet, it is identified with D-jr of Egyptian sources, Biblical Dor, and with Dor/Dora of Greek and Roman sources.[1]

The documented history of the site begins in the Late Bronze Age (though the town itself was founded in the Middle Bronze Age, c. 2000 BCE), and ends in the Crusader period.[بحاجة لمصدر] The port dominated the fortunes of the town throughout its 3,000 year history. Its primary role in all these diverse cultures was that of a commercial entrepôt and a gateway between East and West. The remains of the pre-1948 Palestinian Arab village of Tantura lie a few hundred meters south of the archaeological site, as does the modern kibbutz and resort of Nahsholim.[بحاجة لمصدر]

أصل الاسم

| ||||||||

| djr[2] بالهيروغليفية |

|---|

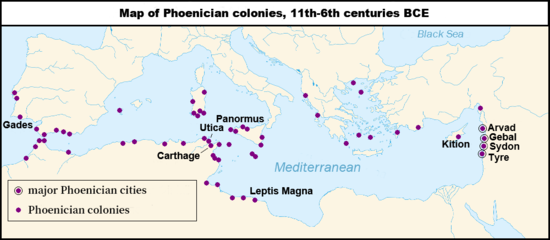

Dor (Hebrew: דוֹר or דאר, meaning "generation", "habitation"), was known as Dora (باليونانية: τὰ Δῶρα)[3] to the Greeks and Romans, and as Dir in the Late Egyptian Story of Wenamun.[2] Dor was successively ruled by Canaanites, Sea Peoples, Israelites, Phoenicians, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans.

The city was known as Dor even before the Greeks arrived or had contact with the peoples in Israel. When the Greeks came to the city and learned its name to be Dor, they ascribed it the identity Dora, the Hellenisation of the name.[بحاجة لمصدر]

الموقع والتعرف عليه

Dora of the classical period has been placed in the ninth mile from Caesarea, on the way to Ptolemais (Acre). Just at the point indicated was the small village of Tantura, probably an Arabic corruption of Dora.[4]

التوراة

Many scholars doubt the historical accuracy of biblical texts relevant to times prior to the 9th century BCE. They suggest that the biblical context for such places as early Dor is more mythology than history.[5]

Scholars who reconcile Bronze and Iron Age history in the Levant with biblical traditions write the following: Dor was an ancient royal city of the Canaanites, (Joshua 12:23) whose ruler was an ally of Jabin king of Hazor against Joshua, (Joshua 11:1,2). In the 12th century, the town appears to have been taken by the Tjekker, and was ruled by them at least as late as the early 11th century BCE. It appears to have been within the territory of the tribe of Asher, though allotted to Manasseh, (Joshua 17:11; Judges 1:27). It was one of Solomon's commissariat districts (Judges 1:27; 1 Kings 4:11).[4]قالب:Clarification

التاريخ والآثار

According to IAA archaeologists, the importance of Dor is that it is the only natural harbour on the Levant coast south of the Ladder of Tyre, and thus was occupied continuously from Phoenician times until the late 18th century.[6] According to Josephus, however, its harbour was inferior to that of Caesarea.[7]

Dor is mentioned in the 3rd-century Mosaic of Rehob as being a place exempt from tithes, seeing that it was not settled by Jews returning from the Babylonian exile in the 4th century BCE. Schürer suggests that Dor, along with Caesarea, may have initially been built towards the end of the Persian period.[8]

الفترة الفارسية

In ca. 460 BCE, the Athenians formed an alliance with the Egyptian leader Inaros against the Persians.[9][10] In order to reach the Nile delta and support the Egyptians, the Athenian fleet had to sail south. Athens had secured landing sites for their triremes as far south as Cyprus, but they needed a way station between Cyprus and Egypt. They needed a naval base on the coast of Lebanon or Palestine, but the Phoenician cities of Sidon and Tyre held much of the mainland coast and those cities were loyal to Persia. Fifty miles south of those cities, however, the Athenians found an isolated and tempting target for establishing a way station.[11]

The Athenians seized Dor from Sidon. Dor had many strategic advantages for the Athenians, starting with its distance from Sidon. The Athenians had a maritime empire built on oared ships. They did not need large tracts of land and instead needed strategically situated coastal sites that had fresh water, provisions and protection from bad weather and enemy attack. Dor had an unfailing freshwater spring near the edge of the sea and to its south a lagoon and sandy beach enclosed by a chain of islets. This was precisely what the Athenian fleet needed for landing their ships and resting their crews. Dor itself was strategically situated. It stood atop a rocky promontory and was protected on its landward side by a marshy swale that formed a natural moat. Beyond the coastal lowlands was Mount Carmel. The town had Persian-built fortifications. In addition to this, the town had straight streets and Phoenician dye pits for the purpling of cloth. For these reasons, Dor became the most remote outpost of the Athenian navy.

الفترة الهلينية

In 138 BC, Dora was the scene of battle between Seleucid emperor Antiochus VII Sidetes and the usurper Diodotus Tryphon, leading to the latter's flight and ultimately his death.[12]

إسرائيل الحديثة

Today in Israel a moshav, situated south of Tel Dor, is named "Dor" after the ancient city.

تاريخ التنقيب

Tel Dor ("the Ruin of Dor") was first investigated in the 1920s by John Garstang, on behalf of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. J. Leibowitz excavated in the lower town around the tell in the 1950s. From 1979 to 1983, Claudine Dauphin excavated a church east of the tell. Avner Raban excavated harbour installations and other constructions mainly south and west of the mound in 1979 - 1984. Underwater surveys around the site were carried out by Kurt Raveh, Shelley Wachsman and Saen Kingsley. Ephraim Stern, of the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University, directed twenty seasons of excavations at the site between 1980 and 2000, in cooperation with the Israel Exploration Society and several Israeli, American, South African and Canadian academic institutions, as well as a large group of German volunteers. With 100–200 staff, students and volunteers per season, Dor was one of the largest and longest-sustained excavation projects in Israel.[بحاجة لمصدر] The eleven excavation areas opened have revealed a wealth of information about the Iron Age, Persian, Hellenistic and Early Roman periods.

Current excavations are being conducted by Ilan Sharon from Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Ayelet Gilboa from University of Haifa in co-operation with the University of Washington,[13] the Weizmann Institute of Science, the University of South Africa, and other institutions. It is a broad international consortium of scholars, jointly pursuing a wide number of different but complementary research objectives.[14]

لقى أثرية

انتاج الصبغة القرمزية في الفترتين الفارسية والهلينية

As of 2001, excavations at the site have yielded an apparatus for the production of a purple dye solution, dating to the Persian and Hellenistic periods, wherein there was still a thick layer of quicklime (calcium oxide) which served, according to scholars, in helping to separate the dye from the mollusks after they had been broken and removed from their shells.[15] These mollusks were primarily imported into the region from other places along the Mediterranean coast, and consisted of species Phorcus turbinatus, Patella caerulea, Stramonita haemastoma, Hexaplex trunculus, among other species.[16]

متحف

The historic 'Glasshouse' museum building, located in kibbutz Nahsholim, some 500 meters south of the site itself, now houses the Center for Nautical and Regional Archaeology at Dor (CONRAD), consisting of the expedition workrooms and a museum displaying the finds from Tel Dor and its region such as documenting the city's importance in the ancient world as a manufacturer of the prestigious azure and crimson colours from sea snails.[17] The house is an old glass-making factory from the 19th century built by Baron Edmond James de Rothschild.[18]

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ Gibson, S., Kingsley, S. and J. Clarke. 1999. "Town and Country in the Southern Carmel: Report on the Landscape Archaeology Project at Dor," Levant 31:71-121.

- ^ أ ب Schipper, Bernd (2005). Die Erzählung des Wenamun: ein Literaturwerk im Spannungsfeld von Politik, Geschichte und Religion. Göttingen: Academic Press Fribourg. p. 45. ISBN 3525530676.

- ^ Josephus, The Jewish War (1:52).

- ^ أ ب Stern, E. 1994. Dor — Ruler of the Seas. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel and Neil Asher Silberman. 2002. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York: Touchstone.

- ^ Freeman-Greenville, G.S.P. (1994). "Reviewed Work: The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land by Ephraim Stern". Journal of the Asiatic Society. Cambridge University Press. 4 (3): 327. JSTOR 25182937.

- ^ Josephus (1981). Josephus Complete Works. Translated by William Whiston. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel Publications. p. 331. ISBN 0-8254-2951-X., s.v. Antiquities 15.9.6. (15.331)

- ^ Schürer, E. (1891). Geschichte des jüdischen Volkes im Zeitalter Jesu Christi [A History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus Christ]. Vol. 1. Translated by Miss Taylor. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 84 (note 121).

- ^ Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Richard Crawley (trans.). 1.104. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus (1946). Library of History. Vol. 4. C. H. Oldfather (trans.). Loeb Classical Library. 11.71.3-6. ISBN 978-0-674-99413-3. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ Hale, John (2009). Lords of the Sea: The Epic Story of the Athenian Navy and the Birth of Democracy. New York: Viking. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0-670-02080-5.

- ^ Josephus, The Jewish War (1:52).

- ^ "University of Washington Excavation".

- ^ For an extensive bibliography of excavations at Dor, see http://www.arts.cornell.edu/jrz3/Tel_Dor_Bibliography.htm

- ^ Spanier, Yossi; Sasson, Avi (2001). Limekilns in the Land of Israel (כבשני סיד בארץ-ישראל) (in العبرية). Ariel: Jerusalem: Land of Israel Museum. p. 8 (Preface). OCLC 48108956.

- ^ Gilboa, Ayelet; Sharon, Ilan; Zorn, Jeffrey R.; Matskevich, Sveta (2018). "Excavations at Dor, Final Report: Volume IIB Area G, The Late Bronze and Iron Ages: Pottery, Artifacts, Ecofacts and other Studies". Qedem Reports (in الإنجليزية). Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. 11: III–340. JSTOR 26493565.

- ^ HaMizgaga Museum Archived 2008-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ History of the Bashan family Archived 2008-11-22 at the Wayback Machine

ببليوگرافيا

- Olami, Y., Sender, S. and Oren, E., Map of Dor (30) (Jerusalem, Israel Antiquities Authority, 2005).

- Full Tel Dor bibliography http://dor.huji.ac.il/bibliography.html

وصلات خارجية

- Tel Dor Project Hebrew University of Jerusalem, University of Haifa and Boston University.

- Gilad Shtienberg et al.: A Neolithic mega-tsunami event in the eastern Mediterranean: Prehistoric settlement vulnerability along the Carmel coast, Israel. In: PLOS ONE. 23 December 2020. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0243619. — Dor paleo-tsunami:

- Evidence for a massive paleo-tsunami at ancient Tel Dor, Israel. On: EurekAlert! Dec 23, 2020.

- Archaeologists Find Evidence of Neolithic Mega-Tsunami in Israel. On: sci-news. Dec 24, 2020.

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 العبرية-language sources (he)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing عبرية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2016

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2021

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2017

- Portal templates with default image

- شعوب البحر

- مدن التوراة

- Archaeological sites in Israel

- المجلس المحلي لساحل الكرمل

- تلال أثرية

- مدن فينيقية