بجع دالماسي

| بجع دالماسي Dalmatian pelican | |

|---|---|

| |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| أصنوفة غير معروفة (أصلحها): | Pelecanus |

| Species: | Template:Taxonomy/PelecanusP. crispus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Template:Taxonomy/PelecanusPelecanus crispus Bruch, 1832

| |

| |

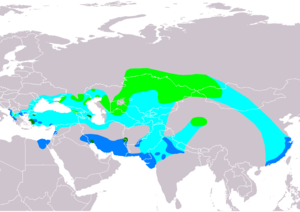

| Distribution map of Dalmatian pelican Breeding Resident Non-breeding Passage | |

البجع الدالماسيّ أو البجع البلقاني أو بجع دلماشيا هو نوع من الطيور وأكبر عضو في عائلة البجع. وربما هو أكبر طائر مائي في العالم، على الرغم من أنه ينافس الطيور في الوزن والطول كأكبر البجع. إلا إنه طير محلق ومتزلق، مع أجنحة تنافس طائر القطرس الكبير، وتطير قطعانها في تزامن رشيق. مع نطاق يمتد عبر معظم وسط أوراسيا، من البحر الأبيض المتوسط في الغرب إلى مضيق تايوان في الشرق، ومن الخليج العربي في الجنوب إلى سيبيريا في الشمال، فهو مهاجر قصير إلى متوسط المسافة بين مناطق التكاثر والشتاء. لا يوجد نوع فرعي معروف لهذا الطائر، ولكن استنادًا إلى اختلاف الحجم بينه وبين البجع الدالماسي الذي عاش خلال العصر البليستوسيني paleosubspecies، P. c ، والمستخرجة أحافيره من بنغادي، بأذربيجان، فقد وصف له تحت نوع منفصل باسم "البجع الدالماسي قبل التاريخيّ" (باللاتينية: Pelecanus crispus palaeocrispus).

كما هو الحال مع طيور البجع الأخرى، فإن الذكور أكبر حجمًا من الإناث ، وبالمثل فإن نظامهم الغذائي يتكون أساسًا من الأسماك. ريش مؤخرتها المجعد وأرجلها الرمادية وريشها الأبيض الفضي هي سمات مميزة، وتبدو الأجنحة رمادية صلبة أثناء الطيران. يكتسب البالغون ريش رقيق في الشتاء، مع ذلك، عندما يخطئون في اعتبارهم طيور البجع البيضاء الكبيرة. تصبح أصواتهم القاسية أكثر وضوحًا خلال موسم التزاوج. تتكاثر عبر Palearctic من جنوب شرق أوروپا إلى روسيا والهند والصين في المستنقعات والبحيرات الضحلة. عادة ما يعودون إلى مواقع التكاثر التقليدية، حيث يكونون أقل اجتماعية من أنواع البجع الأخرى. إن أعشاشها عبارة عن أكوام من النباتات الخام التي توضع على الجزر أو على حصائر كثيفة من النباتات.

شهدت أعداد الأنواع انخفاضًا كبيرًا خلال القرن العشرين، ويرجع ذلك جزئيًا إلى استخدام الأراضي والاضطراب وأنشطة الصيد الجائر. يعيش السكان الأساسيون في روسيا ، ولكن في نطاقها المنغولي يتعرضون لخطر شديد. أدت إزالة خطوط الكهرباء لمنع الاصطدامات أو الصعق بالكهرباء، وإنشاء منصات أو أطواف متداخلة إلى عكس الانخفاضات محليًا.

يُعَدُّ هذا الطائر أكبر طيور البجع على الإطلاق، إذ يبلغ طوله بالمتوسّط 160 إلى 180 سنتيمتراً، ووزنه 11 إلى 15 كيلوغراماً، وباع جناحيه أكثر من ثلاثة أمتار.[2] كما أنه يعد بمتوسط وزنه البالغ 11.5 كيلوغراماً أثقل الطيور القادرة على الطيران بالوزن المتوسط، مع أن ذكور الحباري والإوز العراقي الضخمة يمكن أن تفوقه في الوزن الكليّ.[3][4]

يختلف هذا الطائر عن البجع الأبيض الكبير في أنَّ لديه شعر عنق مجعَّد، وسيقاناً رمادية، وريشاً أبيض مائل إلى الرمادي (بدلاً من أبيض ناصع)، كما أن فكَّه السفليَّ يُصبح أحمر اللون في موسم التزاوج. أما البجع الدالماسي اليافع فيكون لون ريشه رمادياً، وهو لا يملك خطاً زهرياً من الريش على وجهه كالبجع الأبيض الكبير اليافع، والذي يملك أيضاً ريشاً أدكن لوناً من ريش البجع الدالماسي اليافع.

يُهاجر البجع الدالماسي مسافات قصيرة فقط. وهو يحلق على ارتفاعات كبيرة، ويطير في أسراب. غير أنه يبقي رقبته منتصبة عندما لا يكون في وضعية الطيران، مثل البلشونيات. يتغذى البجع الدالماسي بشكل أساسيّ على السمك، الذي يصطاده بالتحليق فوق المسطحات المائية وجرفها بفمه، مبتلعاً الأسماك مع كميات هائلة من المياه.

انحدرت أعداد البجع الدالماسي - مثله في ذلك مثل البجع الأبيض - جرَّاء تدمير بيئته الطبيعية والصيد الجائر.[بحاجة لمصدر] في سنة 1994 كان يوجد منه 2,000 طائر يتكاثرون في أوروبا، معظمهم في أوكرانيا وروسيا ومقدونيا واليونان ورومانيا وبلغاريا وألبانيا. وقد كان البجع الدالماسي أيضاً واحداً من الطيور التي شملتها اتفاقية حماية الطيور المهاجرة الأفرو-أوراسية.

الوصف

التوزيع والموئل

تم العثور على البجع الدالماسي في البحيرات والأنهار و الدلتا و مصبات الأنهار. بالمقارنة مع البجع الأبيض الكبير، فإن الدلماسي ليس مرتبطًا بمناطق الأراضي المنخفضة وسوف يعشش في الأراضي الرطبة المناسبة مع العديد من الارتفاعات. إنه أقل انتهازية في اختيار موائل التكاثر من الأبيض الكبير، وعادة ما يعود إلى موقع تكاثر تقليدي سنة بعد سنة ما لم يصبح غير مناسب تمامًا. خلال فصل الشتاء، عادة ما تبقى طيور البجع الدالماسية في بحيرات خالية من الجليد في أوروبا أو "الجيلز" (بحيرات موسمية) في الهند. كما يزورون، عادة خلال فصل الشتاء، المناطق الساحلية على طول السواحل المحمية للتغذية.[5]

الحركات

يهاجر هذا البجع عادة مسافات قصيرة مع أنماط هجرة مختلفة خلال العام.[6] إنه منتشر في أوروبا، بناءً على فرص التغذية، مع بقاء معظم الطيور الغربية خلال فصل الشتاء في منطقة البحر الأبيض المتوسط. في دلتا الدانوب، يصل البجع الدلماسي في مارس ويغادر بحلول نهاية أغسطس. وهي مهاجرة بشكل أكثر نشاطًا في آسيا، حيث تحلق معظم الطيور التي تتكاثر في روسيا في الشتاء إلى وسط الشرق الأوسط، إلى حد كبير حول إيران عبر شبه القارة الهندية، من سريلانكا ونيبال إلى وسط الهند.[7] البجع الذي يتكاثر في منغوليا شتاء على طول الساحل الشرقي للصين ، بما في ذلك منطقة هونج كونج.[7]

بشكل عام، تفضل الأنواع درجات الحرارة الدافئة نسبيًا. خلال الفترات التي كان المناخ فيها أكثر دفئًا، كان البجع الدلماسي أكثر انتشارًا في أوروبا (اليوم مداها الأوروبي يقتصر على الجزء الجنوبي الشرقي من القارة). بشكل ملحوظ تم العثور على عدد كبير من العظام الأحفورية التي يرجع تاريخها إلى 7400-5000 قبل الحاضر (BP)، بالتزامن مع مناخ الهولوسين الأمثل، في الدنمارك، كما تم العثور عظام تعود إلى ما بين 1900-600 سنة مضت في وسط أوروبا وهولندا وبريطانيا.[8] هذا التفضيل لدرجات الحرارة الأكثر دفئًا مدعوم أيضًا بالحركات المسجلة في التاريخ الحديث، حيث توجد مؤشرات على توسع بطيء في النطاق استجابة لـ التغيرات المناخية الحديثة.[8]

السلوك

التغذية

This pelican feeds almost entirely on fish. Preferred prey species can include common carp (Cyprinus carpio), European perch (Perca fluviatilis), common rudd (Scardinius erythropthalmus), eels, catfish (especially silurids during winter), mullet and northern pike (Esox lucius), the latter having measured up to 50 cm (20 in) when taken.[5][7] In the largest remnant colony, located in Greece, the preferred prey is reportedly the native Alburnus belvica.[9] The Dalmatian pelican requires around 1،200 g (2.6 lb) of fish per day and can take locally abundant smaller fish such as gobies, but usually ignore them in lieu of slightly larger fish.[5][7] It usually forages alone or in groups of only two or three. It normally swims along, placidly and slowly, until it quickly dunks its head underwater and scoops the fish out, along with great masses of water. The water is dumped out of the sides of the pouch and the fish is swallowed. Occasionally it may feed cooperatively with other pelicans by corralling fish into shallow waters and may even cooperate similarly while fishing alongside great cormorants in Greece.[5] Occasionally, the pelican may not immediately eat the fish contained in its gular pouch, so it can save the prey for later consumption.[7] Other small wetlands-dwellers may supplement the diet, including crustaceans, worms, beetles and small water birds, usually nestlings and eggs.[7]

التربية

Among a highly social family in general, Dalmatian pelicans may have the least social inclinations. This species naturally nests in relatively small groups compared to most other pelican species and sometimes may even nest alone. However, small colonies are usually formed, which regularly include upwards of 250 pairs (especially historically). Occasionally, Dalmatian pelicans may mix in with colonies of great white pelicans.[5] Nesting sites selected are usually either islands in large bodies of water (typically lagoons or river deltas[7]) or dense mats of aquatic vegetation, such as extensive reedbeds of Phragmites and Typha. Due to their large size, these pelicans often trample the vegetation in the area surrounding their nests into the muddy substrate and thus nesting sites may become unsuitably muddy after around three years of usage.[9]

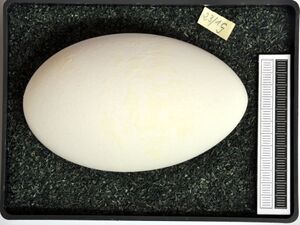

The nest is a moderately-sized pile of grass, reeds, sticks and feathers, usually measuring about 1 m (3.3 ft) deep and 63 cm (25 in) across. Nests are usually located on or near the ground, often being placed on dense floating vegetation. Nests tend to be flimsy until cemented together by droppings. Breeding commences in March or April, about a month before the great white pelican breeds. The Dalmatian pelican lays a clutch of one to six eggs, with two eggs being the norm. Eggs weigh between 120 و 195 g (4.2 و 6.9 oz).[10] Incubation, which is split between both parents, lasts for 30 to 34 days. The chicks are born naked but soon sprout white down feathers. When the young are 6 to 7 weeks of age, the pelicans frequently gather in "pods". The offspring fledge at around 85 days and become independent at 100 to 105 days old. Nesting success relies on local environmental conditions, with anywhere from 58% to 100% of hatchlings successfully surviving to adulthood. Predation on Dalmatian pelicans is relatively poorly known despite the species' threatened status. The nesting sites often insure limited nest predation, though carnivorous mammals which eat eggs and nestlings can access nests when water levels are low enough for them to cross, as has been recorded with wild boars (Sus scrofa) destroying nests in Bulgaria.[9] Golden jackals (Canis aureus) are also known to access and destroy nests when water levels are too low and the same is possibly true of other canids such as foxes, gray wolves (Canis lupus) and dogs (C. l. familiaris), not to mention other predatory animals such as potentially Eurasian lynxes (Lynx lynx). Some eagles may attack too pelicans at colonies, although this is not verified.[11][12][13][14] Large gulls are known to be virulent predators of Dalmatian pelican eggs in Russia, Albania and Turkey.[15][16] Sexual maturity is thought to be obtained at three or four years of age.[5]

الحالة

This species of pelican has declined greatly throughout its range, more so than the white pelican. It is possible that up to 10,000–20,000 pelicans exist at the species level.[9] During the 20th century, the species' numbers underwent a dramatic decline for reasons that are not entirely understood. The most likely reason was habitat loss due to human activities such as the drainage of wetlands and land development. Colonies are regularly disturbed by human activity, and, like all pelicans, the parents may temporarily leave their nest if threatened, which then exposes the chicks to the risk of predation. Occasionally, Dalmatian pelicans may be shot by fishermen who believe the birds are dangerously depleting the fish population and hence threatening their livelihood.[7] While such killings are generally on a small scale, the worry that these pelicans over-exploit the fishing stock persists in many locales. Another probable reason for the decline in the species' population is poaching. In Mongolia, the local people clandestinely kill these pelicans to use or sell their bills as pouches.[7] On a typical day in a commercial Mongolian marketplace, as many as fifty pelican bills may be on offer for sale, and they are considered such a rare prize that ten horses and thirty sheep are considered a fair price to trade for a single pelican.[17] Due to exploitation at all stages of the life cycle, the species is critically endangered in its Mongolian range, with a total population of fewer than 130 individual birds.[9][17] Dalmatian pelicans also regularly fly into power-lines and are killed by electrocution.[9] In Greece, pelicans are often so disturbed by power boats, usually ones bearing tourists—that they become unable to feed and die of malnourishment.[5] In 1994 in Europe there were over a thousand breeding pairs, most of them in Greece, but also in Ukraine, Macedonia, Romania, Bulgaria (Srebarna Nature Reserve) and Albania (Karavasta Lagoon). They have been considered extinct in Croatia since the 1950s, although a single Dalmatian pelican was observed there in 2011.[18] The largest single remaining colony is at Small Prespa Lake (shared between Albania and Greece), with around 1,600 pairs, with approximately 450 pairs left in the Danube Delta.[9] The country with the largest breeding population today, including about 70% of pairs or possibly over 3,000 pairs, is Russia. Worldwide, there are an estimated 3,000–5,000 breeding pairs.[9] One report of approximately 8,000 Dalmatian pelicans in India turned out to be a congregation of misidentified great white pelicans.[5]

The Dalmatian pelican is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies. Conservation efforts have been undertaken on behalf of the species, especially in Europe.[9] Although they normally nest on the ground, Dalmatian pelicans have nested on platforms put out in Turkey, Greece, Bulgaria and Romania in order to encourage them to breed.[5] Rafts over water have also been set up for the species to use in Greece and Bulgaria.[9] Power-lines have also been marked or dismantled in areas adjacent to colonies in these countries. Additionally, water-level management and educational programs may be aiding them at a local level.[9] Although efforts have been undertaken in Asia, there is a much higher rate of poaching, shooting and habitat destruction there, which may make conservation efforts more difficult.[17] In 2012, when unusually frigid winter conditions caused the Caspian Sea to freeze over, it resulted in the death from starvation of at least twenty of the Dalmatian pelicans that overwinter there. Despite local authorities' initial attempts to discourage it, many people there turned out with fish and hand-fed the birds, apparently enabling the huge pelicans to survive the winter.[19]

المصادر

- ^ BirdLife International (2017). "Pelecanus crispus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2017: e.T22697599A119401118. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22697599A119401118.en.

- ^ BirdLife International (2008). "Pelecanus crispus". القائمة الحمراء للأنواع المهددة بالانقراض. Version 2010.2. الاتحاد العالمي للحفاظ على الطبيعة ومواردها. تاريخ الولوج 5 يوليو 2010. Database entry includes a range map and justification for why this species is vulnerable

- ^ del Hoyo, et al., Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 1: Ostrich to Ducks. Lynx Edicons (1992), ISBN 978-84-87334-10-8

- ^ CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHandbook - ^ Efrat, Ron; Harel, Roi; Alexandrou, Olga; Catsadorakis, Giorgos; Nathan, Ran (2019). "Seasonal differences in energy expenditure, flight characteristics and spatial utilization of Dalmatian Pelicans Pelecanus crispus in Greece". Ibis (in الإنجليزية). 161 (2): 415–427. doi:10.1111/ibi.12628. ISSN 1474-919X.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةArkive - ^ أ ب Nikulina, E.A.; U. Schmölcke (2015). "First archaeogenetic results verify the mid-Holocene occurrence of Dalmatian pelican Pelecanus crispus far out of present range". Journal of Avian Biology. 46 (4): 344–351. doi:10.1111/jav.00652.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRedlist - ^ Dalmatian Pelican – Pelecanus crispus : WAZA : World Association of Zoos and Aquariums Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine. WAZA. Retrieved on 2012-08-22.

- ^ Crivelli, A. J. (April 1996). Action Plan for the Dalmatian Pelican (Pelecanus crispus) In Europe. europa.eu

- ^ Dalmatian Pelican (Pelecanus crispus). Planet of Birds (2011-06-08). Retrieved on 2012-08-22.

- ^ Catsadorakis, G., Onmuş, O., Bugariu, S., Gül, O., Hatzilacou, D., Hatzofe, O., & Rudenko, A. (2015). Current status of the Dalmatian pelican and the great white pelican populations of the Black Sea/Mediterranean flyway. Endangered Species Research, 27(2), 119-130.

- ^ Crivelli, A., & Vizi, O. (1981). The Dalmatian pelican, Pelecanus crispus Bruch 1832, a recently world-endangered bird species. Biological Conservation, 20(4), 297-310.

- ^ Krivenko, V. G. (1994). Pelicans in the former USSR (Vol. 27). International Waterfowl and Wetlands Research Bureau.

- ^ Peja, N., Sarigul, G., Siki, M., & Crivelli, A. J. (1996). The Dalmatian pelican, Pelecanus crispus, nesting in Mediterranean lagoons in Albania and Turkey. Colonial Waterbirds, 184-189.

- ^ أ ب ت Nyambayar, B.; Bräunlich, A.; Tseveenmyadag, N.; Shar, S. & Gantogs, S. (2007). "Conservation of the critically endangered east Asian population of Dalmatian Pelican Pelecanus crispus in western Mongolia" (PDF). BirdingASIA. 7: 68–74. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-27.

- ^ "The Dalmatian Pelican Returns to the Neretva Delta, Croatia". World Migratory Bird Day. 13 May 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Trapped Dalmatian pelicans hand-fed in frozen Caspian Sea. Bbc.co.uk (2012-02-21). Retrieved on 2012-08-22.

وصلات خارجية

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- IUCN Red List near threatened species

- Automatic taxobox cleanup

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- طيور أذربيجان

- طيور پاكستان

- طيور الصحراء الغربية

- بجع

- طيور آسيا

- طيور أوروپا

- أنواع القائمة الحمراء غير المحصنة

- أنواع القائمة الحمراء القريبة من الخطر

- طيور غرب آسيا

- طيور كازاخستان

- طيور وسط آسيا

- طيور وصفت في 1832

- أصنوفات سماها كارل فريدريش بروخ