الزجاج الروماني

انتقل صناع كوميا، ولترنوم، وأكويليا، من صنع الخزف إلى صنع الزجاج الفني الجميل. ومن أشهر أمثلة هذه الآنية الزجاجية مزهرية پورتلاند وأجمل منها "المزهرية الزجاجية الزرقاء" التي عثر عليها في بمبي والتي نقش عليها عيد خمري لباخوس نقشاً جميلاً ينبض بالحياة(19). ويقول پلني الأكبر واسترابون: إن فن صنع الزجاج قد نـُقل في عهد تيبريوس من صيدا والإسكندرية إلى رومة، وسرعان ما أخرج فنانوه قنينات صغيرة، وقداحاً وطاسات، وأواني أخرى متعددة الألوان دقيقة الصنع، جميلة المنظر أصبحت في وقت ما مطلب الأثرياء وجامعي الروائع الفنية. وقد عرض في عهد نيرون ستة آلاف سسترس ثمناً لقدحين صغيرين من الزجاج المعروف في هذه الأيام باسم "ميلفيوري" Millefiori أو "الزهرات الألف"، صنعا بصهر عصى زجاجية مختلفة اللون. وكان أغلى من هذين ثمناً مزهريات "مورهين" Murrhine التي جيء بها من آسية وأفريقية. وكانت تصنع بوضع خيوط رفيعة من الزجاج الأبيض والأرجواني بعضهما بجوار بعض للحصول على الرسم المطلوب، ثم إشعال النار فيها، أو ترصيع جسم أبيض شفاف بقطع من الزجاج الملون، وقد جاء پومپي بروائع من هذا النوع إلى رومة بعد انتصاره على مثرداتس. واحتفظ أغسطس لنفسه بكأس كليوبطرة المصنوعة من زجاج مرهين، وإن كان قد صهر صحافها الذهبية. وقد دفع نيرون مليون سسترس ثمناً لقدح من هذا النوع، وكسر پترونيوس قدحاً آخر وهو يحتضر حتى لا يقع في يد نيرون. ويمكن القول بوجه عام إن الرومان لم يفقهم أحد في صنع الزجاج؛ وقلَّ أن يوجد في العالم مجموعات فنية أثمن من مجموعة الآنية الزجاجية الرومانية المحفوظة في المتحف البريطاني وفي متحف متروپوليتان للفنون بنيويورك.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

نمو صناعة الزجاج الروماني

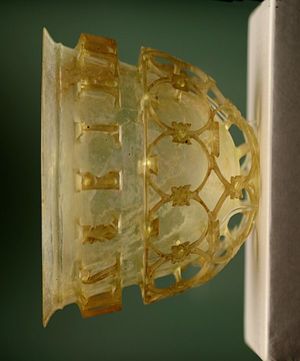

This pyxis is exemplary of elite Roman glassware, ca. late 1st century BCE. Walters Art Museum, بلتيمور. | |

الانتاج

المكونات

مقالة مفصلة: زجاج

مقالة مفصلة: زجاج

صناعة الزجاج

التدوير

الأنماط

تقنيات صناعة القدور

التقنيات الزخرفية

أنماط الزجاج المصبوب

الزجاج الذهبي

الكيمياء والألوان

انظر أيضا ألوان الزجاج الحديثة.

| الملوِن | المحتوى | تعليقات | أحوال الفرن | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 'Aqua' | Iron(II) oxide (FeO) |

‘Aqua’, a pale blue-green colour, is the common natural colour of untreated glass. Many early Roman vessels are this colour.[1] | ||

| عديم اللون | Iron(III) oxide (Fe2O3) |

Colourless glass was produced in the Roman period by adding either antimony or manganese oxide.[2] This oxidised the iron (II) oxide to iron (III) oxide, which although yellow, is a much weaker colourant, allowing the glass to appear colourless. The use of manganese as a decolourant was a Roman invention first noted in the Imperial period; prior to this, antimony-rich minerals were used.[2] However, antimony acts as a stronger decolourant than manganese, producing a more truly colourless glass; in Italy and northern Europe antimony or a mixture of antimony and manganese continued to be used well into the 3rd century.[3] | ||

| عنبر | مركبات الحديد-الرصاص | 0.2%-1.4% S[2] 0.3% Fe |

Sulfur is likely to have entered the glass as a contaminant of natron, producing a green tinge. Formation of iron-sulfur compounds produces an amber colour. | Reducing |

| قرمزي | Manganese (such as pyrolusite) |

Around 3%[2] | Oxidising[2] | |

| أزرق وأخضر | نحاس | 2%-13%[2] | The natural ‘aqua’ shade can be intensified with the addition of copper. During the Roman period this was derived from the recovery of oxide scale from scrap copper when heated, to avoid the contaminants present in copper minerals.[2] Copper produced a translucent blue moving towards a darker and denser green. | Oxidising[2] |

| أخضر داكن | رصاص | By adding lead, the green colour produced by copper could be darkened.[2] | ||

| أزرق ملكي إلى بحرية | كوبالت | 0.1%[2] | Intense colouration | |

| أزرق مسحوق | أزرق مصري[2] | |||

| أحمر معتم إلى بني (هيماتينوم حسب پلني) | نحاس رصاص |

>10% Cu 1% - 20% Pb[2] |

Under strongly reducing conditions, copper present in the glass will precipitate inside the matrix as cuprous oxide, making the glass appear brown to blood red. Lead encourages precipitation and brilliance. The red is a rare find, but is known to have been in production during the 4th, 5th and later centuries on the continent.[4] | Strongly reducing |

| الأبيض | Antimony (such as stibnite) |

1-10%[2] | Antimony reacts with the lime in the glass matrix to precipitate calcium antimonite crystals creating a white with high opacity.[2] | Oxidising |

| الأصفر | أنتيمون ورصاص (such as bindheimite).[2] |

Precipitation of lead pyroantimonate creates an opaque yellow. Yellow rarely appears alone in Roman glass, but was used for the mosaic and polychrome pieces.[2] |

These colours formed the basis of all Roman glass, and although some of them required high technical ability and knowledge, a degree of uniformity was achieved.[2]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةAllen98 - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةFleming - ^ Jackson, Caroline (2005). "Making colourless glass in the Roman period". Archaeometry. 47 (4): 763–780.

- ^ Evison, V. I., 1990. Red marbled glass, Roman to Carolingian. Annales du 11e Congres. Amsterdam.