الجدي (نجم)

| بيانات الرصـد Epoch J2000 Equinox | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Ursa Minor |

| α UMi A | |

| Right ascension | 02س 31د 49.09ث[1] |

| Declination | +89° 15′ 50.8″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 1.98[2] (1.86 – 2.13)[3] |

| α UMi B | |

| Right ascension | 02س 30د 41.63ث[4] |

| Declination | +89° 15′ 38.1″[4] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 8.7[2] |

| الخـصـائص | |

| النوع الطيفي | F7Ib + F6[5] |

| U-B دليل الألوان | 0.38[2] |

| B-V دليل الألوان | 0.60[2] |

| النوع المتغير | Classical Cepheid[3] |

| علم القياسات الفلكية | |

| السرعة القطرية (Rv) | −17[6] كم/ث |

| الحركة الحقيقية (μ) | RA: 198.8±0.20[1] mas/yr Dec.: −15±0.30[1] mas/س |

| اختلاف المنظر (π) | 7.54 ± 0.11[1] mas |

| المسافة | 323–433[7] س ض (99–133[7] ف ن) |

| القدر المطلق (MV) | −3.6 (α UMi Aa)[2] 3.6 (α UMi Ab)[2] 3.1 (α UMi B)[2] |

| المـوقـع (بالنسبة إلى α UMi Aa) | |

| Component | α UMi Ab |

| Epoch of observation | 2005.5880 |

| Angular distance | 0.172″ |

| Position angle | 231.4° |

| المـوقـع (بالنسبة إلى α UMi Aa) | |

| Component | α UMi B |

| Epoch of observation | 2005.5880 |

| Angular distance | 18.217″ |

| Position angle | 230.540° |

| المدار[8] | |

| الرئيسي | α UMi Aa |

| الرفيق | α UMi Ab |

| الدورة (P) | 29.416±0.028 س |

| Semimajor axis (a) | 0.12955±0.00205" (≥2.90±0.03 AU[9]) |

| اختلاف المركز (e) | 0.6354±0.0066 |

| ميل (i) | 127.57±1.22° |

| خط طول العقدة (Ω) | 201.28±1.18° |

| نقطة التقارب الحقبة (T) | 2016.831±0.044 |

| Argument of periastron (ω) (primary) | 304.54±0.84° |

| Semi-amplitude (K1) (primary) | 3.762±0.025 كم/s |

| التـفـاصـيل | |

| α UMi Aa | |

| الكتلة | 5.13±0.28[8] M☉ |

| نصف القطر | 37.5[10]–46.27[8] R☉ |

| الضياء (الإشعاعي) | 1,260[10] L☉ |

| جاذبية السطح (ج) | 2.2[11] س.ج.ث. |

| درجة الحرارة | 6015[12] ك |

| المعدنية | 112% solar[13] |

| الدوران | 119 days[5] |

| تسارع الدوران (v sin i) | 14[5] كم/ث |

| العمر | 45 - 67[14] م.س. |

| α UMi Ab | |

| الكتلة | 1.316[8] M☉ |

| نصف القطر | 1.04[2] R☉ |

| الضياء (الإشعاعي) | 3[2] L☉ |

| العمر | >500[14] م.س. |

| α UMi B | |

| الكتلة | 1.39[2] M☉ |

| نصف القطر | 1.38[12] R☉ |

| الضياء (الإشعاعي) | 3.9[12] L☉ |

| جاذبية السطح (log g) | 4.3[12] ث.ج.ث. |

| درجة الحرارة | 6900[12] ك |

| تسارع الدوران (v sin i) | 110[12] كم/ث |

| العمر | 1.5[14] م.س. |

| تسميات أخرى | |

| مراجع قواعد البيانات | |

| SIMBAD | data |

نجم الجدي أو ألفا الدب الأصغر (بالإنكليزية: Polaris) هو ألمع نجوم كوكبة الدب الأصغر ونجم الشمال الحالي، حيث أنه قريب جداً من القطب السماوي الشمالي. الجدي هو نجم متعدد (ثلاثي) ويبعد عن الأرض مسافة 430 سنة ضوئية ويبلغ لمعانه 2 قدر ظاهري، وكتلته تبلغ ستة كتل شمسية[15][16]. ربما نجم الجدي هو أكثر نجوم النصف الشمالي للكرة الأرضية شهرة بسبب أهميته لمعرفة الاتجاهات (انظر فقرة: "نجم الشمال" أدناه). الجدي هو عملاق عظيم يبلغ ضياؤه 1500 ضعف ضياء الشمس. نجم الجدي هو نجم متغير من المتغيرات القيفاوية، حيث أن ضوءه يتغير بشكل ضئيل كل مدة قريبة من 4 أيام[17].

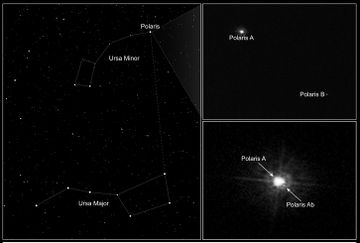

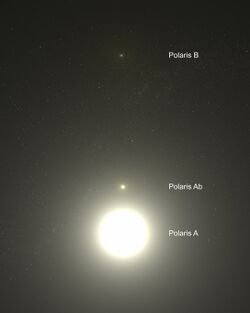

النظام النجمي

يُرافق نجم الجدي نجم من نجوم التسلسل الرئيسي ومن القدر التاسع[17] اسمه "الجدي ب". يُمكن أن يُرى حتى بتلسكوب متواضع، وقد كان أول من لاحظه هو ويليام هرشل في عام 1780. وفي عام 1929 اُكتشف عبر تحليل طيف الجدي أنه يَملك رفيقاً آخر وهو نجم قزم وشديد القرب منه. وفي عام 2006 نشرت ناسا صوراً من تلسكوب هابل تُظهر نجم الجدي مع رفيقيه بوضوح. النجم الأكثر قرباً يَبعد مسافة 18.5 و.ف (2.46 ساعة ضوئية) فقط عن "الجدي أ" (وهذا ما يُعادل بُعد كوكب أورانوس عن الشمس)، وهذا يُفسر سبب اختفاء ضوئه بين ضوء "الجدي أ" الذي يفوقه ضياءً وحجماً بكثير[18]. ويدور "الجدي أب" (النجم الأقرب إلى "الجدي أ") في مدار شاذ يُتمه مرة كل 30 سنة حول نظام الجدي النجمي.[17]

The variable radial velocity of Polaris A was reported by W. W. Campbell in 1899, which suggested this star is a binary system.[19] Since Polaris A is a known cepheid variable, J. H. Moore in 1927 demonstrated that the changes in velocity along the line of sight were due to a combination of the four-day pulsation period combined with a much longer orbital period and a large eccentricity of around 0.6.[20] Moore published preliminary orbital elements of the system in 1929, giving an orbital period of about 29.7 years with an eccentricity of 0.63. This period was confirmed by proper motion studies performed by B. P. Gerasimovič in 1939.[21]

As part of her doctoral thesis, in 1955 E. Roemer used radial velocity data to derive an orbital period of 30.46 y for the Polaris A system, with an eccentricity of 0.64.[22] K. W. Kamper in 1996 produced refined elements with a period of 29.59±0.02 years and an eccentricity of 0.608±0.005.[23] In 2019, a study by R. I. Anderson gave a period of 29.32±0.11 years with an eccentricity of 0.620±0.008.[9]

There were once thought to be two more widely separated components—Polaris C and Polaris D—but these have been shown not to be physically associated with the Polaris system.[24][25]

الرصد

التغير

Polaris Aa, the supergiant primary component, is a low-amplitude Population I classical Cepheid variable, although it was once thought to be a type II Cepheid due to its high galactic latitude. Cepheids constitute an important standard candle for determining distance, so Polaris, as the closest such star,[9] is heavily studied. The variability of Polaris had been suspected since 1852; this variation was confirmed by Ejnar Hertzsprung in 1911.[27]

The range of brightness of Polaris is given as 1.86–2.13,[3] but the amplitude has changed since discovery. Prior to 1963, the amplitude was over 0.1 magnitude and was very gradually decreasing. After 1966, it very rapidly decreased until it was less than 0.05 magnitude; since then, it has erratically varied near that range. It has been reported that the amplitude is now increasing again, a reversal not seen in any other Cepheid.[5]

The period, roughly 4 days, has also changed over time. It has steadily increased by around 4.5 seconds per year except for a hiatus in 1963–1965. This was originally thought to be due to secular redward (lower temperature) evolution across the Cepheid instability strip, but it may be due to interference between the primary and the first-overtone pulsation modes.[28][29][30] Authors disagree on whether Polaris is a fundamental or first-overtone pulsator and on whether it is crossing the instability strip for the first time or not.[10][30][31]

The temperature of Polaris varies by only a small amount during its pulsations, but the amount of this variation is variable and unpredictable. The erratic changes of temperature and the amplitude of temperature changes during each cycle, from less than 50 K to at least 170 K, may be related to the orbit with Polaris Ab.[11]

Research reported in Science suggests that Polaris is 2.5 times brighter today than when Ptolemy observed it, changing from third to second magnitude.[32] Astronomer Edward Guinan considers this to be a remarkable change and is on record as saying that "if they are real, these changes are 100 times larger than [those] predicted by current theories of stellar evolution".

In 2024, researchers led by Nancy Evans at the Harvard & Smithsonian, have studied with more accuracy the Polaris' smaller companion orbit using the CHARA Array. During this observation campaign they have succeeded in shooting Polaris features on its surface; large bright places and dark ones have appeared in close-up images, changing over time. Further, Polaris diameter size has been re-measured to 46 R☉, using the Gaia distance of 446±1 light-years, and its mass was determined at 5.13 M☉.[8]

الدور كنجم قطبي

Because Polaris lies nearly in a direct line with the Earth's rotational axis "above" the North Pole—the north celestial pole—Polaris stands almost motionless in the sky, and all the stars of the northern sky appear to rotate around it. Therefore, it makes an excellent fixed point from which to draw measurements for celestial navigation and for astrometry. The elevation of the star above the horizon gives the approximate latitude of the observer.[34]

In 2018 Polaris was 0.66° (39.6 arcminutes) away from the pole of rotation (1.4 times the Moon disc) and so revolves around the pole in a small circle 1.3° in diameter. It will be closest to the pole (about 0.45 degree, or 27 arcminutes) soon after the year 2100.[35] Because it is so close to the celestial north pole, its right ascension is changing rapidly due to the precession of Earth's axis, going from 2.5h in AD 2000 to 6h in AD 2100. Twice in each sidereal day Polaris's azimuth is true north; the rest of the time it is displaced eastward or westward, and the bearing must be corrected using tables or a rule of thumb. The best approximation[33] is made using the leading edge of the "Big Dipper" asterism in the constellation Ursa Major. The leading edge (defined by the stars Dubhe and Merak) is referenced to a clock face, and the true azimuth of Polaris worked out for different latitudes.

The apparent motion of Polaris towards and, in the future, away from the celestial pole, is due to the precession of the equinoxes.[36] The celestial pole will move away from α UMi after the 21st century, passing close by Gamma Cephei by about the 41st century, moving towards Deneb by about the 91st century.

The celestial pole was close to Thuban around 2750 BC,[36] and during classical antiquity it was slightly closer to Kochab (β UMi) than to Polaris, although still about 10° from either star.[37] It was about the same angular distance from β UMi as to α UMi by the end of late antiquity. The Greek navigator Pytheas in ca. 320 BC described the celestial pole as devoid of stars. However, as one of the brighter stars close to the celestial pole, Polaris was used for navigation at least from late antiquity, and described as ἀεί φανής (aei phanēs) "always visible" by Stobaeus (5th century), also termed Λύχνος (Lychnos) akin to a burner or lamp and would reasonably be described as stella polaris from about the High Middle Ages and onwards, both in Greek and Latin. On his first trans-Atlantic voyage in 1492, Christopher Columbus had to correct for the "circle described by the pole star about the pole".[38] In Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar, written around 1599, Caesar describes himself as being "as constant as the northern star", though in Caesar's time there was no constant northern star. Despite its relative brightness, it is not, as is popularly believed, the brightest star in the sky.[39]

Polaris was referenced in Nathaniel Bowditch's 1802 book, American Practical Navigator, where it is listed as one of the navigational stars.[40]

نجم الشمال

حالياً نجم الشمال هو نجم الجدي (هناك فرق بين نجم القطب ونجم الشمال، فهناك قطبان للكرة السماوية)، ونجم القطب (والجدي حالياً هو نجم القطب الشمالي) هو اسمٌ يُطلق على ألمع نجمٍ قريبٍ من أحد قطبي الكرة الأرضية. حيث أنه يَكون قريباً من محور دوران السماء لدرجة أنه شبه ثابت، وبما أنه يَكون قريباً قليلاً من الأفق فيُمكن معرفة الاتجاهات بواسطته (إلا في المناطق القريبة من أحد قطبي الكرة الأرضية فيكون نجم القطب عالياً في السماء). ولذلك فقد كان له أهميّة كبيرة جداً في العصور القديمة، وربما كان وما زال أشهر نجوم السماء على الإطلاق بسبب هذا[41]. وحالياً يَبعد نجم الجدي مسافة 0.7ْ عن القطب السماوي الشمالي (1.4 ضعف قطر القمر الظاهري)[36]. لن يبقى نجم الجدي هو نجم الشمال للأبد، فنجم الشمال يتغير باستمرار نتيجة لتغير زاوية محور دوران الأرض، فمثلاً كان نجم الشمال قبل 14,000 عام (12,000 ق.م) هو النسر الواقع وسوف يَعود كذلك بعد 12,000 عام (14,000م). وقد كان نجم الثعبان في كوكبة التنين هو نجم الشمال قبل 5000 عام[42].

الاستدلال على نجم الجدي

مقالة مفصلة: الدليلان

مقالة مفصلة: الدليلان

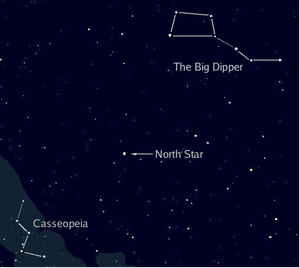

توجد كوكبتان لامعتان قريبتان من نجم الجدي حالياً هما الدب الأكبر وذات الكرسي، ومّما يجعل الأمر سهلاً أن هاتين الكوكبتين هما من الكوكبات أبدية الظهور. لكن بالرغم من أن هاتين الكوكبتين تُصنفان ضمن الكوكبات أبدية الظهور إلى أن معظمهما أو كل نجومهما تختفي تحت الأفق لمدة وجيزة أثناء اليوم. ومع ذلك فيُمكن الاستدلال على موقع نجم الجدي بأي وقت لأن هاتين الكوكبتين تقعان على جهتين متقابلتين من نجم الشمال، وبالتالي فإن غابت إحداهما تحت الأفق فسوف تكون الأخرى مرتفعة في السماء.

توجد سبع نجوم لامعة في كوكبة الدب الأكبر تُسمى "بنات نعش الكبرى"، واثنان من هذه النجوم السبعة يسميان الدليلين، وهما المراق والدبة. وقد أخذا اسمهما من إمكانيّة الاستدلال على موقع نجم الجدي بواسطتهما. وذلك بمد خط وهمي منهما بحيث يكونان على استقامة واحدة إلى نجم الجدي. أيضاً يُمكن معرفة موقعه بواسطة كوكبة ذات الكرسي والتي تُشكل حرف "W". فإذا أخذنا الجهة اليُمنى من الكوكبة والتي تُشكل حرف "V" أكثر انتظاماً من الذي تشكله الجهة اليُسرى، ومددنا خطاً وهمياً من وسطها بحيث يكون على مسافة واحدة من كلا ضلعي حرف "V" فإنه سوف يَصل إلى نجم الجدي أيضاً[43].

أسماء الجدي في الثقافات المختلفة

}}

كان العرب القدماء يُسمونه غالباً الجدي، لكن كان يُسمى أسماءً أخرى أيضاً مثل "الركبة"[44]. أما المايا فقد سموه "رأس القرد"، وهو رمز إله النجم القطبي عند المايا. وقد سماه الهنود "دهرفا" (Dhurva) والتي تعني "الثابت" نسبة إلى ثبوته في السماء. أما حديثاً فقد أصبح اسمه المُعتمد في معظم اللغات هو "Polaris" نسبة إلى "Pole" والتي تعني "قطب" باللغة الإنكليزية[45].

In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[46] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN's first bulletin of July 2016[47] included a table of the first two batches of names approved by the WGSN; which included Polaris for the star α Ursae Minoris Aa.

In antiquity, Polaris was not yet the closest naked-eye star to the celestial pole, and the entire constellation of Ursa Minor was used for navigation rather than any single star. Polaris moved close enough to the pole to be the closest naked-eye star, even though still at a distance of several degrees, in the early medieval period, and numerous names referring to this characteristic as polar star have been in use since the medieval period. In Old English, it was known as scip-steorra ("ship-star")[بحاجة لمصدر]. In the Old English rune poem, the T-rune is apparently associated with "a circumpolar constellation", or the planet Mars.[48]

In the Hindu Puranas, it became personified under the name Dhruva ("immovable, fixed").[49] In the later medieval period, it became associated with the Marian title of Stella Maris "Star of the Sea" (so in Bartholomaeus Anglicus, c. 1270s),[50] due to an earlier transcription error.[51] An older English name, attested since the 14th century, is lodestar "guiding star", cognate with the Old Norse leiðarstjarna, Middle High German leitsterne.[52]

The ancient name of the constellation Ursa Minor, Cynosura (from the Greek κυνόσουρα "the dog's tail"),[53] became associated with the pole star in particular by the early modern period. An explicit identification of Mary as stella maris with the polar star (Stella Polaris), as well as the use of Cynosura as a name of the star, is evident in the title Cynosura seu Mariana Stella Polaris (i.e. "Cynosure, or the Marian Polar Star"), a collection of Marian poetry published by Nicolaus Lucensis (Niccolo Barsotti de Lucca) in 1655.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Its name in traditional pre-Islamic Arab astronomy was al-Judayy الجدي ("the kid", in the sense of a juvenile goat ["le Chevreau"] in Description des Etoiles fixes),[54] and that name was used in medieval Islamic astronomy as well.[55][56] In those times, it was not yet as close to the north celestial pole as it is now, and used to rotate around the pole.

It was invoked as a symbol of steadfastness in poetry, as "steadfast star" by Spenser. Shakespeare's sonnet 116 is an example of the symbolism of the north star as a guiding principle: "[Love] is the star to every wandering bark / Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken." In Julius Caesar, he has Caesar explain his refusal to grant a pardon by saying, "I am as constant as the northern star/Of whose true-fixed and resting quality/There is no fellow in the firmament./The skies are painted with unnumbered sparks,/They are all fire and every one doth shine,/But there's but one in all doth hold his place;/So in the world" (III, i, 65–71). Of course, Polaris will not "constantly" remain as the north star due to precession, but this is only noticeable over centuries.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In Inuit astronomy, Polaris is known as Nuutuittuq (syllabics: ᓅᑐᐃᑦᑐᖅ).

In traditional Lakota star knowledge, Polaris is named "Wičháȟpi Owáŋžila". This translates to "The Star that Sits Still". This name comes from a Lakota story in which he married Tȟapȟúŋ Šá Wíŋ, "Red Cheeked Woman". However, she fell from the heavens, and in his grief Wičháȟpi Owáŋžila stared down from "waŋkátu" (the above land) forever.[57]

The Plains Cree call the star in Nehiyawewin: acâhkos êkâ kâ-âhcît "the star that does not move" (syllabics: ᐊᒑᐦᑯᐢ ᐁᑳ ᑳ ᐋᐦᒌᐟ).[58] In Mi'kmawi'simk the star is named Tatapn.[59]

In the ancient Finnish worldview, the North Star has also been called taivaannapa and naulatähti ("the nailstar") because it seems to be attached to the firmament or even to act as a fastener for the sky when other stars orbit it. Since the starry sky seemed to rotate around it, the firmament is thought of as a wheel, with the star as the pivot on its axis. The names derived from it were sky pin and world pin.[بحاجة لمصدر]

المسافة

Many recent papers calculate the distance to Polaris at about 433 light-years (133 parsecs),[28] based on parallax measurements from the Hipparcos astrometry satellite. Older distance estimates were often slightly less, and research based on high resolution spectral analysis suggests it may be up to 110 light years closer (323 ly/99 pc).[7] Polaris is the closest Cepheid variable to Earth so its physical parameters are of critical importance to the whole astronomical distance scale.[7] It is also the only one with a dynamically measured mass.

| Year | Component | Distance, ly (pc) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | A | 330 ly (101 pc) | Turner[29] |

| 2007[A] | A | 433 ly (133 pc) | Hipparcos[1] |

| 2008 | B | 359 ly (110 pc) | Usenko & Klochkova[12] |

| 2013 | B | 323 ly (99 pc) | Turner, et al.[7] |

| 2014 | A | ≥ 385 ly (≥ 118 pc) | Neilson[60] |

| 2018 | B | 521 ly (160pc) | Bond et al.[61] |

| 2018 | B | 445.3 ly (136.6 pc)[B] | Gaia DR2[62] |

| 2020 | B | 447.6 ly (137.2pc) | Gaia DR3[4] |

| A New revision of observations from 1989 to 1993, first published in 1997 |

| B Statistical distance calculated using a weak distance prior |

The Hipparcos spacecraft used stellar parallax to take measurements from 1989 and 1993 with the accuracy of 0.97 milliarcseconds (970 microarcseconds), and it obtained accurate measurements for stellar distances up to 1,000 pc away.[63] The Hipparcos data was examined again with more advanced error correction and statistical techniques.[1] Despite the advantages of Hipparcos astrometry, the uncertainty in its Polaris data has been pointed out and some researchers have questioned the accuracy of Hipparcos when measuring binary Cepheids like Polaris.[7] The Hipparcos reduction specifically for Polaris has been re-examined and reaffirmed but there is still not widespread agreement about the distance.[64]

The next major step in high precision parallax measurements comes from Gaia, a space astrometry mission launched in 2013 and intended to measure stellar parallax to within 25 microarcseconds (μas).[65] Although it was originally planned to limit Gaia's observations to stars fainter than magnitude 5.7, tests carried out during the commissioning phase indicated that Gaia could autonomously identify stars as bright as magnitude 3. When Gaia entered regular scientific operations in July 2014, it was configured to routinely process stars in the magnitude range 3 – 20.[66] Beyond that limit, special procedures are used to download raw scanning data for the remaining 230 stars brighter than magnitude 3; methods to reduce and analyse these data are being developed; and it is expected that there will be "complete sky coverage at the bright end" with standard errors of "a few dozen μas".[67] Gaia Data Release 2 does not include a parallax for Polaris, but a distance inferred from it is 136.6±0.5 pc (445.5 ly) for Polaris B,[62] somewhat further than most previous estimates and several times more accurate. This was further improved to 137.2±0.3 pc (447.6 ly), upon publication of the Gaia Data Release 3 catalog on 13 June 2022 which superseded Gaia Data Release 2.[4]

في الثقافة الشعبية

Polaris is depicted in the flag and coat of arms of the Canadian Inuit territory of Nunavut,[68] the flag of the U.S. states of Alaska and Minnesota,[69] and the flag of the U.S. city of Duluth, Minnesota.[70][71]

معرض صور

Big Dipper and Ursa Minor in relation to Polaris

Polaris pictured in the coat of arms of Utsjoki[بحاجة لمصدر]

انظر أيضا

المراجع

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر Evans, N. R.; Schaefer, G. H.; Bond, H. E.; Bono, G.; Karovska, M.; Nelan, E.; Sasselov, D.; Mason, B. D. (2008). "Direct Detection of the Close Companion of Polaris with The Hubble Space Telescope". The Astronomical Journal. 136 (3): 1137. arXiv:0806.4904. Bibcode:2008AJ....136.1137E. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/136/3/1137. S2CID 16966094.

- ^ أ ب ت Samus, N. N.; Kazarovets, E. V.; et al. (2017). "General Catalogue of Variable Stars". Astronomy Reports. 5.1. 61 (1): 80–88. Bibcode:2017ARep...61...80S. doi:10.1134/S1063772917010085. S2CID 125853869.

- ^ أ ب ت ث قالب:Cite Gaia DR3

- ^ أ ب ت ث Lee, B. C.; Mkrtichian, D. E.; Han, I.; Park, M. G.; Kim, K. M. (2008). "Precise Radial Velocities of Polaris: Detection of Amplitude Growth". The Astronomical Journal. 135 (6): 2240. arXiv:0804.2793. Bibcode:2008AJ....135.2240L. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/6/2240. S2CID 12176373.

- ^ Campbell, William Wallace (1913). "The radial velocities of 915 stars". Lick Observatory Bulletin. 229: 113. Bibcode:1913LicOB...7..113C. doi:10.5479/ADS/bib/1913LicOB.7.113C.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Turner, D. G.; Kovtyukh, V. V.; Usenko, I. A.; Gorlova, N. I. (2013). "The Pulsation Mode of the Cepheid Polaris". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 762 (1): L8. arXiv:1211.6103. Bibcode:2013ApJ...762L...8T. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/762/1/L8. S2CID 119245441.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Evans, Nancy Remage; Schaefer, Gail H.; Gallenne, Alexandre; Torres, Guillermo; Horch, Elliott P.; Anderson, Richard I.; Monnier, John D.; Roettenbacher, Rachael M.; Baron, Fabien; Anugu, Narsireddy; Davidson, James W.; Kervella, Pierre; Bras, Garance; Proffitt, Charles; Mérand, Antoine (2024-08-01). "The Orbit and Dynamical Mass of Polaris: Observations with the CHARA Array". The Astrophysical Journal. 971 (2): 190. arXiv:2407.09641. Bibcode:2024ApJ...971..190E. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ad5e7a. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ أ ب ت Anderson, R. I. (March 2019). "Probing Polaris' puzzling radial velocity signals. Pulsational (in-)stability, orbital motion, and bisector variations". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 623: 17. arXiv:1902.08031. Bibcode:2019A&A...623A.146A. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201834703. S2CID 119467242. A146.

- ^ أ ب ت Fadeyev, Y. A. (2015). "Evolutionary status of Polaris". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 449 (1): 1011–1017. arXiv:1502.06463. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.449.1011F. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv412. S2CID 118517157.

- ^ أ ب Usenko, I. A.; Miroshnichenko, A. S.; Klochkova, V. G.; Yushkin, M. V. (2005). "Polaris, the nearest Cepheid in the Galaxy: Atmosphere parameters, reddening and chemical composition". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 362 (4): 1219. Bibcode:2005MNRAS.362.1219U. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.09353.x.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Usenko, I. A.; Klochkova, V. G. (2008). "Polaris B, an optical companion of the Polaris (α UMi) system: Atmospheric parameters, chemical composition, distance and mass". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 387 (1): L1. arXiv:0708.0333. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.387L...1U. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2008.00426.x. S2CID 18848139.

- ^ Cayrel de Strobel, G.; Soubiran, C.; Ralite, N. (2001). "Catalogue of [Fe/H] determinations for FGK stars: 2001 edition". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 373: 159–163. arXiv:astro-ph/0106438. Bibcode:2001A&A...373..159C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20010525. S2CID 17519049.

- ^ أ ب ت (2021) "The Curious Case of the North Star: The Continuing Tension Between Evolution Models and Measurements of Polaris" in RR Lyrae/Cepheid 2019: Frontiers of Classical Pulsators. 529.

- ^ Wieland page 9: Table 5 gives mass of component A as 6.0 ±0.5 and P as 1.54 ±0.25 solar masses

- ^ Polaris: Mass and Multiplicity, http://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0609759, retrieved on 2009-04-13 (URL for full PDF) (Evans et al support Wieland's prediction: "preliminary mass of 5.0 ± 1.5 M⊙ for the Cepheid and 1.38 ± 0.61 M⊙ for the close companion.)

- ^ أ ب ت نجم الجدي:تعريفتاريخ الولوج 4 مارس 2010

- ^ Evans, N. R.; Schaefer, G.; Bond, H.; Bono, G.; Karovska, M.; Nelan, E.; Sasselov, D. (January 9, 2006). "Direct detection of the close companion of Polaris with the Hubble Space Telescope". American Astronomical Society 207th Meeting.

- ^ Campbell, W. W. (October 1899). "On the variable velocity of Polaris in the line of sight". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 11: 195–199. Bibcode:1899PASP...11..195C. doi:10.1086/121339. S2CID 122429136.

- ^ Moore, J. H. (August 1927). "Note on the Longitude of the Lick Observatory". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 39 (230): 249. Bibcode:1927PASP...39..249M. doi:10.1086/123734. S2CID 119469812.

- ^ Roemer, Elizabeth (May 1965). "Orbital Motion of Alpha Ursae Minoris from Radial Velocities". Astrophysical Journal. 141: 1415. Bibcode:1965ApJ...141.1415R. doi:10.1086/148230.

- ^ Wyller, A. A. (December 1957). "Parallax and orbital motion of spectroscopic binary Polaris from photographs taken with the 24-inch Sproul refractor". Astronomical Journal. 62: 389–393. Bibcode:1957AJ.....62..389W. doi:10.1086/107559.

- ^ Kamper, Karl W. (June 1996). "Polaris Today". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 90: 140. Bibcode:1996JRASC..90..140K.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةWielen - ^ Evans, Nancy Remage; Guinan, Edward; Engle, Scott; Wolk, Scott J.; Schlegel, Eric; Mason, Brian D.; Karovska, Margarita; Spitzbart, Bradley (2010). "Chandra Observation of Polaris: Census of Low-mass Companions". The Astronomical Journal. 139 (5): 1968. Bibcode:2010AJ....139.1968E. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/139/5/1968.

- ^ "MAST: Barbara A. Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes". Space Telescope Science Institute. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Hertzsprung, Ejnar (August 1911). "Nachweis der Veränderlichkeit von α Ursae Minoris". Astronomische Nachrichten (in الألمانية). 189 (6): 89. Bibcode:1911AN....189...89H. doi:10.1002/asna.19111890602.

- ^ أ ب Evans, N. R.; Sasselov, D. D.; Short, C. I. (2002). "Polaris: Amplitude, Period Change, and Companions". The Astrophysical Journal. 567 (2): 1121. Bibcode:2002ApJ...567.1121E. doi:10.1086/338583.

- ^ أ ب Turner, D. G.; Savoy, J.; Derrah, J.; Abdel-Sabour Abdel-Latif, M.; Berdnikov, L. N. (2005). "The Period Changes of Polaris". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 117 (828): 207. Bibcode:2005PASP..117..207T. doi:10.1086/427838.

- ^ أ ب Neilson, H. R.; Engle, S. G.; Guinan, E.; Langer, N.; Wasatonic, R. P.; Williams, D. B. (2012). "The Period Change of the Cepheid Polaris Suggests Enhanced Mass Loss". The Astrophysical Journal. 745 (2): L32. arXiv:1201.0761. Bibcode:2012ApJ...745L..32N. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/745/2/L32. S2CID 118625176.

- ^ Engle, Scott G; Guinan, Edward F; Harmanec, Petr (2018). "Toward Ending the Polaris Parallax Debate: A Precise Distance to Our Nearest Cepheid from Gaia DR2". Research Notes of the AAS. 2 (3): 126. Bibcode:2018RNAAS...2..126E. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/aad2d0. S2CID 126329676.

- ^ Irion, R (2004). "American Astronomical Society meeting. As inconstant as the Northern Star". Science. 304 (5678): 1740–1. doi:10.1126/science.304.5678.1740b. PMID 15205508. S2CID 129246155.

- ^ أ ب "A visual method to correct a ship's compass using Polaris using Ursa Major as a point of reference". Archived from the original on August 27, 2010. Retrieved Aug 7, 2016.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةKaler - ^ Meeus, J. (1990). "Polaris and the North Pole". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 100: 212. Bibcode:1990JBAA..100..212M.

- ^ أ ب ت Ridpath, Ian, ed. (2004). Norton's Star Atlas. New York: Pearson Education. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-13-145164-3.

Around 4800 years ago Thuban (قالب:GreekFont Draconis) lay a mere 0°.1 from the pole. Deneb (قالب:GreekFont Cygni) will be the brightest star near the pole in about 8000 years' time, at a distance of 7°.5.

خطأ استشهاد: وسم<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Nor" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ Ridpath, Ian (2018). "Ursa Minor, the Little Bear". Star Tales. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ Columbus, Ferdinand (1960). The Life of the Admiral Christopher Columbus by His Son Fredinand. Translated by Keen, Benjamin. London: Folio Society. p. 74.

- ^ Geary, Aidan (June 30, 2018). "Look up, be patient and 'think about how big the universe is': Expert tips for stargazing this summer". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

- ^ Bowditch, Nathaniel; National Imagery and Mapping Agency (2002). "15". The American practical navigator : an epitome of navigation. Paradise Cay Publications. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-939837-54-0.

- ^ Jean Meeus, Mathematical Astronomy Morsels Ch.50; Willmann-Bell 1997

- ^ Jean Meeus, Mathematical Astronomy Morsels Ch.50; Willmann-Bell 1997

- ^ العثور على نجم القطبتاريخ الولوج 4 مارس 2010

- ^

"Cynosure". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Cynosure". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ Smith, Robert W. (1943) The Last Days: Scriptural and Secular Prophecies Pertaining to the Last Days. Salt Lake City: Pyramid Press, p. 218

- ^ "International Astronomical Union | IAU". www.iau.org. Retrieved 2019-01-19.

- ^ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1" (PDF).

- ^ Dickins, Bruce (1915). Runic and heroic poems of the old Teutonic peoples. p. 18.; Dickins' "a circumpolar constellation" is attributed to L. Botkine, La Chanson des Runes (1879).

- ^ Daniélou, Alain (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism. Princeton/Bollingen (1964); Inner Traditions/Bear & Co. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-892-813544.

- ^ Halliwell, J. O., ed. (1856). The Works of William Shakespeare. Vol. 5. p. 40.

- ^ قالب:Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^ Kluge, Friedrich; Götze, Alfred (1943). Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache. Walter de Gruyter. p. 355. ISBN 978-3-111-67185-7.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian (28 June 2018). Star Tales. Lutterworth Press. ISBN 978-0-7188-4782-1.

- ^ ʻAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʻUmar Ṣūfī (1874). Description des Etoiles fixes. Commissionnaires de lÁcadémie Impériale des sciences. p. 45.

- ^ Al-Sufi, AbdulRahman (964). "Book Of Fixed Stars".

- ^ Schjellerup, Hans (1874). Description des Etoiles fixes. p. 45.

- ^ "Winter Solstice is Sacred Time a Time to Carry One Another by Dakota Wind". 27 December 2019.

- ^ "Polaris". Plains Cree Dictionary. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Lebans, Jim (29 September 2022). "Mi'kmaw astronomer says we should acknowledge we live under Indigenous skies". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Neilson, H. R. (2014). "Revisiting the fundamental properties of the Cepheid Polaris using detailed stellar evolution models". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 563: A48. arXiv:1402.1177. Bibcode:2014A&A...563A..48N. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201423482. S2CID 119252434.

- ^ Bond, Howard E; Nelan, Edmund P; Remage Evans, Nancy; Schaefer, Gail H; Harmer, Dianne (2018). "Hubble Space Telescope Trigonometric Parallax of Polaris B, Companion of the Nearest Cepheid". The Astrophysical Journal. 853 (1): 55. arXiv:1712.08139. Bibcode:2018ApJ...853...55B. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aaa3f9. S2CID 118875464.

- ^ أ ب Bailer-Jones, C. A. L; Rybizki, J; Fouesneau, M; Mantelet, G; Andrae, R (2018). "Estimating Distance from Parallaxes. IV. Distances to 1.33 Billion Stars in Gaia Data Release 2". The Astronomical Journal. 156 (2): 58. arXiv:1804.10121. Bibcode:2018AJ....156...58B. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aacb21. S2CID 119289017.

- ^ Van Leeuwen, F. (1997). "The Hipparcos Mission". Space Science Reviews. 81 (3/4): 201–409. Bibcode:1997SSRv...81..201V. doi:10.1023/A:1005081918325. S2CID 189785021.

- ^ Van Leeuwen, F. (2013). "The HIPPARCOS parallax for Polaris". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 550: L3. arXiv:1301.0890. Bibcode:2013A&A...550L...3V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220871. S2CID 119284268.

- ^ Liu, C.; Bailer-Jones, C. A. L.; Sordo, R.; Vallenari, A.; et al. (2012). "The expected performance of stellar parametrization with Gaia spectrophotometry". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 426 (3): 2463. arXiv:1207.6005. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.426.2463L. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21797.x. S2CID 1841271.

- ^ Martín-Fleitas, J.; Sahlmann, J.; Mora, A.; Kohley, R.; Massart, B.; l'Hermitte, J.; Le Roy, M.; Paulet, P. (2014). Oschmann, Jacobus M; Clampin, Mark; Fazio, Giovanni G; MacEwen, Howard A (eds.). "Enabling Gaia observations of naked-eye stars". Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2014: Optical. Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2014: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave. 9143: 91430Y. arXiv:1408.3039. Bibcode:2014SPIE.9143E..0YM. doi:10.1117/12.2056325. S2CID 119112009.

- ^ T. Prusti (2016), "The Gaia mission", Astronomy and Astrophysics 595: A1, doi:, Bibcode: 2016A&A...595A...1G

- ^ "The Coat of Arms of Nunavut. (n.d.)". Legislative Assembly of Nunavut. Retrieved 2021-09-15.

- ^ Swanson, Stephen (2023-12-15). "YouTuber's critique of Minnesota state flag finalists draws 1 million views". CBS Minnesota. Retrieved 2024-08-28.

- ^ site staff (2019-08-14). "Duluth Picks New City Flag". Fox 21. Retrieved 2024-09-03.

- ^ Kate Van Daele (2019-08-14). "City of Duluth selects new flag" (PDF). City of Duluth. Retrieved 2024-09-05.

| سبقه كوكب و فرقد |

Pole star 500–3000 |

تبعه Gamma Cephei |

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2022

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2023

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2018

- Articles containing إينوكتيتوت-language text

- Articles containing Plains Cree-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2023

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- جدي

- F-type supergiants

- F-type main-sequence stars

- Bayer objects

- أجرام زيج بون

- أجرام فلامستيد

- أجرام زيج هنري دريپر

- أجرام هيپاركوس

- Bright Star Catalogue objects

- نجوم بأسماء خاصة

- Northern pole stars

- Classical Cepheid variables

- Suspected variables

- Triple star systems

- كوكبة الدب الأصغر

- أنظمة نجمية ثلاثية

- نجوم الشمال

- نجوم عربية

![Polaris pictured in the coat of arms of Utsjoki[بحاجة لمصدر]](/w/images/thumb/e/e6/Utsjoki.vaakuna.svg/107px-Utsjoki.vaakuna.svg.png)