إنتي

Inti is the ancient Inca sun god. He is revered as the national patron of the Inca state. Although most consider Inti the sun god, he is more appropriately viewed as a cluster of solar aspects, since the Inca divided his identity according to the stages of the sun.[1] Worshiped as a patron deity of the Inca Empire,[2] Pachacuti is often linked to the origin and expansion of the Inca Sun Cult.[3][4] The most common belief was that Inti was born of Viracocha, who had many titles, chief among them being the God of Creation.[5]

The word inti is not of Quechua origin but a loanword from Puquina.[6] Borrowing from Puquina explains why historically unrelated languages such as Quechua, Aymara and Mapuche have similar words for the Sun.[6][7] Similitudes are not only linguistic but also symbolically as in Mapuche and Central Andean cosmology the Sun (Inti/Antu) and the Moon (Quilla/Cuyen) are spouses.[8]

الأساطير والتاريخ

Inti and his sister, Mama Quilla (also spelled Mama Killa), the Moon goddess were generally considered benevolent deities. She then conceived and bore him two children. Their court is served by the Rainbow, the Pleiades, Venus, and others. Manco Cápac, the founding Inca ancestor, was thought to have been the son of Inti. According to myth, Inti taught Manco Cápac and his daughter Mama Ocllo the arts of civilization. However, another legend identifies Manco Cápac as the son of Viracocha. In a different myth, Inti is the son of the Earth goddess Pachamama and the sky god. Inti also becomes the second husband of Pachamama[بحاجة لمصدر]

Inti ordered his children to build the Inca capital where a divine golden bar or wedge they carried with them penetrated the earth. Incas believed that this happened in the city of Cusco. The Inca ruler was considered to be the living representative of Inti. Pachacuti is often linked to the origin and expansion of the Inca Sun Cult.[3][4]

The Willaq Umu was the high priest of the Sun (Inti). His position placed him as the second most powerful person in the kingdom. He was directly underneath the Sapa Inca, and they were often brothers. The emperor and his family were believed to be descended from Inti.[9]

Spanish conquistadors captured a great golden disk representing Inti in 1571 and sent it to the pope via Spain. It has since been lost and may have been converted to bullion.[بحاجة لمصدر]

There is another interpretation of the creation event that leads to a conflict between Viracocha and Inti in which there is an argument over what the creation of the Sun means and whether it should be worshipped as a separate entity.

Some sources identify the central figure of the Gateway of the Sun as Inti and others as Viracocha, and that the Sun was just one of many creations.[10]

العبادة

The Inca dedicated many ceremonies to the Sun in order to ensure the Sapa Inca's welfare.[2] The sun was also important to the Incas, particularly the people of the highlands, because it was necessary for the production of crops like maize and other grains.[9] The sun's heat was also thought to cause rain. During the rainy season the sun was hotter and brighter, while during the dry season it was weaker.[11]

The Incas would set aside large quantities of natural and human resources throughout the empire for Inti. Each conquered province was supposed to dedicate a third of their lands and herds to Inti as mandated by the Inca. Each major province would also have a Sun Temple in which male and female priests would serve.[2] The female priests were the mamakuna, who were chosen from the aqllakuna ("chosen women"), and they would weave special cloth and brew chicha for festivities and sacrifices to Inti.[12]

Additionally, the chief temple of the Inca state religion was the Qurikancha in Cusco. Within this temple were wall niches in which the bodies of previous emperors and rulers were exhibited along with various statues of Inti in certain festivals. Some figures of Inti also depicted him in human form with a hollowed out midsection that was filled with a concoction made of gold dust and the ashes of the Inca kings' hearts.[13]

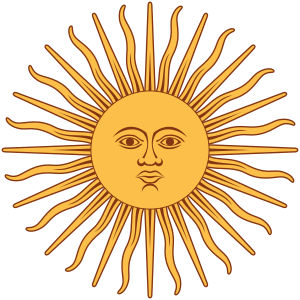

Inti is represented as a golden disk with rays and a human face. Many such disks were supposedly held in Cusco as well as in shrines throughout the empire, especially at Qurikancha, where the most significant image of Inti was discovered by anthropologists. This representation, adorned with ear spools, a pectoral, and a royal headband, was known as punchaw (Quechua for day, also spelled punchao). This image of Inti was also said to have lions and serpents projecting from its form.[14]

The worship of Inti and the rise of the Inti cult are considered to be exploitations of religion for political purposes, since the Inca king was increasingly identified with the sun god. This grew into a form of divine patronage and the convenience of these comparisons for Inca emperors is crucial.[15]

The female priests had a different specialized purpose during the solstice, as the sun was said to have foretold of a death that would end the line of the Sun in the Inca Empire. After the solstice, the mamakuna would begin a fasting area, to hopefully bring them closer to the sorrow of the sun, so that they might understand what was going to happen and prevent the wrong-doing from happening.[16]

There is another aspect of worship that does not involve the priests, but rather the people of Inca. Because they believed that they were descended from the sun. More specifically the ruling class were descended from the sun and that connected the people to that holiness. This led to every time a member of Inca society travelled, they were doing so as a symbol of Inti and their nation, which led to the need to be holy to enter certain cities, and even to travel at all within the empire.[17] The items offered in worship to Inti for which there is archeological evidence in include simple prayers, food, coca leaves and woven cloth, as well as animals, blood and human beings.[18][19]

The temples often have the most embellishment, with the designs inside being done of gold and other jewels. Thus, adding to the status of those who worshipped within the building for the sun, and to show that there is some sacrifice to the god by giving the temple these glories that would no longer be used for the people of the civilization, but the god instead.[20]

إنتي رايمي

The festival of Inti Raymi honors the sun god and was originally meant to celebrate the start of a new planting season.[21] It now attracts many tourists each year to Cusco, which was[22] the ancient capital of the Inca Empire. The name of the festival, Inti Raymi, translates into "sun festival" [1] and was held during the Southern Hemisphere's winter solstice,[22] which is the shortest day of the year. This fell around June 24 in the Inca Empire.

This festival was attended by the four sectors of Tawantinsuyu. Military captains, government officials, and the vassals who attended were dressed in their best costumes and carried their best weapons and instruments.

Preparation for the festival of Inti Raymi began with a fast of three days, where there were no fires lit and the people abstained from having sexual intercourse. This festival would last for nine days, and during this time the people consumed massive amounts of food and drink.[22] There were many sacrifices as well, which were all performed on the first day. After the nine days everyone would leave with the permission of the Inca.

تقسيمات الهوية

Corresponding with the three diurnal stages of the sun, Inti's identity is also divided into three primary subcomplexes, which are the father, son, and brother. The first of these is Apu Inti ("supreme Inti"). He represents the father and is sometimes known as "The Lord Sun."[13] The second is Churi Inti, or "Son Inti," who represents the son of Inti and is often known as "Daylight." The third and final division of Inti is Inti Wawqi ("Sun brother", or "Inti brother", also spelled Inti-Guauqui, Inti-Huaoqui). Inti Wawqi also represents the sun god in his specific position as the founding father of Inca reign and the center of the state's official ancestor cult.[1]

In astronomy, Apu Inti and Churi Inti can actually be separated from one another along an astronomical axis. This is because they are associated with the summer and winter solstices respectively. Inti Wawqi, however, is not associated with an astronomical location.[21]

The other main theory regarding the separation of the sun involves the duties that Inti provided rather than being different stages of the sun. The belief states that one of the suns was for the actual star in the sky that gave light and heat to the planet, that one of the suns was for the daytime where the sun was the highlight of the sky instead of the moon, and that one was for the power to grow things relating to the agricultural significance of the sun worship.[20]

الرمزية

The sun can be seen in culture across the Andean culture even before the Inca empire dominated the land. This connection to the sun could be due to the heavy importance of agriculture in these societies, as without consistent sunlight, most crops do not fare well. The sun was also connected to the rain, and the ability for the clouds to rain, which is another aspect that is necessary for the development of crops, leading even further into the importance of life and specifically agriculture in this society. This is why Inti is the god that is most worshipped in the culture outside of the creator god, Viracocha.

One example of the symbolism that could be found outside of the Incan culture would be the Sun Gate in Tiwanaku. The sun gate found here has significant impact on the solar archaeology of the site as it shows great insight into the position of the sun on days of importance, such as both solstices and equinoxes.

The Sun has clear importance to the Inca civilization, which can even be seen in the architecture of the empire. The Ushnus, were buildings where the leading soldiers would pledge to be loyal towards the leadership of the Inca leadership, and these buildings have a deep connection to the sun.[23] These sites would provide connections during the solar zenith passes. The impact of this can be seen that the buildings were done in relation to the understanding that they had toward the sun, and that they paid attention to the horizon at various important days of the year, that way they could make these connections. Thus, providing another symbol that allows for the Sun to be seen as a key feature of their culture. This is hypothesized to be a reference to when the ceremonies could occur, so that they would be blessed by the sun.

On top of being used in the symbolism of the past, and the sun having an importance in the culture and religion there, the sun is still used on important symbolic figures within countries that were once part of the Inca Empire, proving that while this religion is no longer the foothold of these nations as it once was, the mythology and features are still present today. While these are not guaranteed to have connections to the god, Inti, the cultural significance of the sun has clearly carried over throughout the changes of empires and through the colonization of the Andes.

The Sun is also depicted on the coat of arms of Bolivia, coat of arms of Argentina and coat of arms of Ecuador, as well as the historical flag of Peru. All these countries were historically part of the Inca Empire. It is also depicted on the Hispanic flag.

The Sun of May possibly has its roots in Inti as well and can be found on the Flag of Argentina and Flag of Uruguay.

Inti on the flag of Peru, as designed by José Bernardo de Tagle, 1822

Shield of the coat of arms of Bolivia, with Inti rising above the mountains

Shield of the coat of arms of Ecuador, with Inti above the land

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ أ ب ت Conrad and Demarest 1984, pg.108

- ^ أ ب ت D'Altroy 2003, pg.148

- ^ أ ب Steele & Allen 2004, pg. 246

- ^ أ ب D'Altroy 2003, pg. 147

- ^ Cobo and Hamilton 1990, pg. 22

- ^ أ ب Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo. (2013). Las lenguas de los incas: el puquina, el aimara y el quechua. Frankfurt, Alemania: Peter Lang Academic Research.

- ^ Moulian, Rodrígo; Catrileo, María; Landeo, Pablo (2015). "Afines quechua en el vocabulario mapuche de Luis de Valdivia" [Akins Quechua words in the Mapuche vocabulary of Luis de Valdivia]. Revista de lingüística teórica y aplicada (in الإسبانية). 53 (2). doi:10.4067/S0718-48832015000200004. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

- ^ Moulian, Rodrigo; Catrileo, María; Hasler, Felipe (2018). "Correlatos en las constelaciones semióticas del sol y de la luna en las áreas centro y sur andinas" [Correspondence of semiotic sun and moon constellations in the central and southern andes]. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino (in الإسبانية). 23 (2). doi:10.4067/S0718-68942018000300121.

- ^ أ ب Bushnell 1957, pg. 131

- ^ Silverman and Isbell 2008, pg. 734

- ^ Steele & Allen 2004, pg. 245–246

- ^ D'Altroy 2003, pg.189

- ^ أ ب Conrad and Demarest 1984, pg. 115

- ^ Suarez and George 2011, pg. 129

- ^ Suarez and George 2011, pg. 86–87

- ^ Cobo and Hamilton 1990, pg. 27

- ^ Protzen 2009, pg. 117

- ^ "Why the Incas offered up child sacrifices". the Guardian (in الإنجليزية). 2013-08-03. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

- ^ MacQuarrie, Kim (2007). The last days of the Incas. New York. ISBN 978-0-7432-6049-7. OCLC 77767591.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ أ ب Cobo and Hamilton 1990, pg. 26

- ^ أ ب Conrad and Demarest 1984, pg. 109

- ^ أ ب ت D'Altroy 2003, pg. 154–155

- ^ Moyano 2014, pg. 189

المراجع

- Bushnell, G. H. S. (1957). Peru. London: Thames and Hudsonar

- Cobo, Bernabé and Hamilton, Roland. Inca Religion and Customs. 1st ed., University of Texas Press, 1990.

- Conrad, Geoffrey W. and Arthur A. Demarest. (1984). Religion and Empire: The Dynamics of Aztec and Inca Expansionism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- D'Altroy, Terence N. (2003). The Incas. Blackwell Publishing.

- Fash, William and Mary E. Lyons. (2005). The Ancient American World (The World in Ancient Times). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lane, Kevin. (2011). Inca. In Timothy Insoll (Ed.), Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual and Religion. (pg. 571–584). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Littleton, C. Scott. (2005). Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology. Volume II. Marshall Cavendish Press.

- Moyano, Ricardo. Astronomical Observations on Inca Ushnus in the Southern Andes. London: Archetype. NASA, 2014

- Parker, Janet, et al. (2007). Mythology: Myths, Legends, and Fantasies. Global Book Publishing.

- Protzen, Jean-Pierre. Architecture- Design Methods-Inca Structures. Kasel University Press, 2009.

- Silverman, Helaine and Isbell, William H.. Southern American Archaeology. Springer, 2008.

- Steele, Paul R., & Allen, Catherine J. (2004). Handbook of Inca Mythology. ABC-CLIO, Inc.

- Suarez, Ananda Cohen and Jeremy James George. (2011). Handbook to Life in the Inca World. (pg. 86–129). New York: Facts on File Library of World History.

وصلات خارجية

Media related to إنتي at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to إنتي at Wikimedia Commons

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2021

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2023

- Aymara gods

- Inca gods

- Solar gods

- Primordial teachers

- Heraldic beasts

- Incest in mythology

- Tutelary gods