أهريمان

| Ahriman | |

|---|---|

Spirit of evil, chaos, destruction, daevas | |

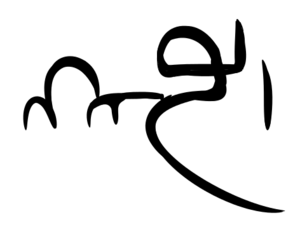

The Middle Persian word ʾhlmn' (Ahreman) in Book Pahlavi script. The word is traditionally always written upside-down. | |

| الانتماء | الزرادشتية |

| المنطقة | إيران الكبرى |

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| الزرادشتية |

|---|

|

أنگرا ماينيو (Angra Mainyu ؛ /ˈæŋrə ˈmaɪnjuː/؛ آڤستان: 𐬀𐬢𐬭𐬀⸱𐬨𐬀𐬌𐬥𐬌𐬌𐬎 Aŋra Mainiiu) or Ahriman (فارسية: اهريمن) is the Avestan name of Zoroastrianism's hypostasis of the "destructive/evil spirit" and the main adversary in Zoroastrianism either of the Spenta Mainyu, the "holy/creative spirits/mentality", or directly of Ahura Mazda, the highest deity of Zoroastrianism. The Middle Persian equivalent is Ahriman 𐭠𐭧𐭫𐭬𐭭𐭩 (anglicised pronunciation: /ˈɑːrɪmən/). The name can appear in English-language works as Ahrimanes.[1]

In the Avesta

In Zoroaster's revelation

Avestan angra mainyu "seems to have been an original conception of Zoroaster's."[2] In the Gathas, which are the oldest texts of Zoroastrianism and are attributed to Zoroaster, angra mainyu is not yet a proper name.[أ] In the one instance in these hymns where the two words appear together, the concept spoken of is that of a mainyu ("mind", "spirit" or otherwise an abstract energy etc.)[ب] that is angra ("destructive", "chaotic", "disorderly", "inhibitive", "malign" etc., of which a manifestation can be anger). In this single instance – in Yasna 45.2 – the "more bounteous of the spirits twain" declares angra mainyu to be its "absolute antithesis".[2]

A similar statement occurs in Yasna 30.3, where the antithesis is however aka mainyu, aka being the Avestan language word for "evil". Hence, aka mainyu is the "evil spirit" or "evil mind" or "evil thought," as contrasted with spenta mainyu, the "bounteous spirit" with which Ahura Mazda conceived of creation, which then "was".

The aka mainyu epithet recurs in Yasna 32.5, when the principle is identified with the daevas that deceive humankind and themselves. While in later Zoroastrianism, the daevas are demons, this is not yet evident in the Gathas: Zoroaster stated that the daevas are "wrong gods" or "false gods" that are to be rejected, but they are not yet demons.[3] Some have also proposed a connection between Angra Mainyu and the sage Angiras of the Rigveda.[4][5] If this is true, it could be understood as evidence for a religious schism between the deva-worshiping Vedic Indo-Aryans and early Zoroastrians.

In Yasna 32.3, these daevas are identified as the offspring, not of Angra Mainyu, but of akem manah, "evil thinking". A few verses earlier it is however the daebaaman, "deceiver" – not otherwise identified but "probably Angra Mainyu"[2] – who induces the daevas to choose achistem manah – "worst thinking." In Yasna 32.13, the abode of the wicked is not the abode of Angra Mainyu, but the abode of the same "worst thinking". "One would have expected [Angra Mainyu] to reign in hell, since he had created 'death and how, at the end, the worst existence shall be for the deceitful' (Y. 30.4)."[2]

In the Younger Avesta

Yasna 19.15 recalls that Ahura Mazda's recital of the Ahuna Vairya invocation puts Angra Mainyu in a stupor. In Yasna 9.8, Angra Mainyu creates Aži Dahaka, but the serpent recoils at the sight of Mithra's mace (Yasht 10.97, 10.134). In Yasht 13, the Fravashis defuse Angra Mainyu's plans to dry up the earth, and in Yasht 8.44 Angra Mainyu battles but cannot defeat Tishtrya and so prevent the rains. In Vendidad 19, Angra Mainyu urges Zoroaster to turn from the good religion by promising him sovereignty of the world. On being rejected, Angra Mainyu assails Zoroaster with legions of demons, but Zoroaster deflects them all. In Yasht 19.96, a verse that reflects a Gathic injunction, Angra Mainyu will be vanquished and Ahura Mazda will ultimately prevail.

In Yasht 19.46ff, Angra Mainyu and Spenta Mainyu battle for possession of khvaraenah, "divine glory" or "fortune". In some verses of the Yasna (e.g. Yasna 57.17), the two principles are said to have created the world, which seems to contradict the Gathic principle that declares Ahura Mazda to be the sole creator and which is reiterated in the cosmogony of Vendidad 1. In that first chapter, which is the basis for the 9th–12th-century Bundahishn, the creation of sixteen lands by Ahura Mazda is countered by the Angra Mainyu's creation of sixteen scourges such as winter, sickness, and vice. "This shift in the position of Ahura Mazda, his total assimilation to this Bounteous Spirit [Mazda's instrument of creation], must have taken place in the 4th century BC at the latest; for it is reflected in Aristotle's testimony, which confronts Areimanios with Oromazdes (apud Diogenes Laertius, 1.2.6)."[2]

Yasht 15.43 assigns Angra Mainyu to the nether world, a world of darkness. So also Vendidad 19.47, but other passages in the same chapter (19.1 and 19.44) have him dwelling in the region of the daevas, which the Vendidad asserts is in the north. There (19.1, 19.43–44), Angra Mainyu is the daevanam daevo, "daeva of daevas" or chief of the daevas. The superlative daevo.taema is however assigned to the demon Paitisha ("opponent"). In an enumeration of the daevas in Vendidad 1.43, Angra Mainyu appears first and Paitisha appears last. "Nowhere is Angra Mainyu said to be the creator of the daevas or their father."[2]

In Zurvanite Zoroastrianism

Zurvanism – a historical branch of Zoroastrianism that sought to theologically resolve a dilemma found in a mention of antithetical "twin spirits" in Yasna 30.3 – developed a notion that Ahura Mazda (MP: Ohrmuzd) and Angra Mainyu (MP: Ahriman) were twin brothers, with the former being the epitome of good and the latter being the epitome of evil. This mythology of twin brotherhood is only explicitly attested in the post-Sassanid Syriac and Armenian polemic such as that of Eznik of Kolb. According to these sources the genesis saw Zurvan as an androgynous deity, existing alone but desiring offspring who would create "heaven and hell and everything in between." Zurvan then sacrificed for a thousand years. Towards the end of this period, Zurvan began to doubt the efficacy of sacrifice and in the moment of this doubt Ohrmuzd and Ahriman were conceived: Ohrmuzd for the sacrifice and Ahriman for the doubt. Upon realizing that twins were to be born, Zurvan resolved to grant the first-born sovereignty over creation. Ohrmuzd perceived Zurvan's decision, which he then communicated to his brother. Ahriman then preempted Ohrmuzd by ripping open the womb to emerge first. Reminded of the resolution to grant Ahriman sovereignty, Zurvan conceded, but limited kingship to a period of 9000 years, after which Ohrmuzd would rule for all eternity.[6] Eznik of Kolb also summarizes a myth in which Ahriman is said to have demonstrated an ability to create life by creating the peacock.

The story of Ahriman's ripping open the womb to emerge first suggests that Zurvanite ideology perceived Ahriman to be evil by choice, rather than always having been intrinsically evil (as found, for example, in the cosmological myths of the Bundahishn). And the story of Ahriman's creation of the peacock suggests that Zurvanite ideology perceived Ahriman to be a creator figure like Ormazd. This is significantly different from what is found in the Avesta (where Mazda's stock epithet is dadvah, "Creator", implying Mazda is the Creator), as well as in Zoroastrian tradition where creation of life continues to be exclusively Mazda's domain, and where creation is said to have been good until it was corrupted by Ahriman and the devs.

في التقليد الزرادشتي

In the Pahlavi texts of the 9th–12th century, Ahriman (written ʼhl(y)mn) is frequently written upside down "as a sign of contempt and disgust."[2]

In the Book of Arda Viraf 5.10, the narrator – the 'righteous Viraf' – is taken by Sarosh and Adar to see "the reality of God and the archangels, and the non-reality of Ahriman and the demons" as described by the German philologist and orientalist Martin Haug, whose radical interpretation was to change the faith in the 19th century (see "In present-day Zoroastrianism" below). [7] This idea of "non-reality" is also expressed in other texts, such as the Denkard, a 9th-century "encyclopedia of Mazdaism",[8] which states Ahriman "has never been and never will be."[2] In chapter 100 of Book of the Arda Viraf, which is titled 'Ahriman', the narrator sees the "Evil spirit, ... whose religion is evil [and] who ever ridiculed and mocked the wicked in hell."

In the Zurvanite Ulema-i Islam (a Zoroastrian text, despite the title), "Ahriman also is called by some name by some people and they ascribe evil unto him but nothing can also be done by him without Time.[بحاجة لمصدر]" A few chapters later, the Ulema notes that "it is clear that Ahriman is a non-entity" but "at the resurrection Ahriman will be destroyed and thereafter all will be good; and [change?] will proceed through the will of God." In the Sad Dar, the world is described as having been created by Ohrmuzd and become pure through his truth. But Ahriman, "being devoid of anything good, does not issue from that which is owing to truth." (62.2)

Book of Jamaspi 2.3 notes that "Ahriman, like a worm, is so much associated with darkness and old age, that he perishes in the end."[9] Chapter 4.3 recalls the grotesque legend of Tahmurasp (Avestan: Taxma Urupi) riding Angra Mainyu for thirty years (cf. Yasht 15.12, 19.29) and so preventing him from doing evil. In chapter 7, Jamasp explains that the Indians declare Ahriman will die, but "those, who are not of good religion, go to hell."

The Bundahishn, a Zoroastrian account of creation completed in the 12th century has much to say about Ahriman and his role in the cosmogony. In chapter 1.23, following the recitation of the Ahuna Vairya, Ohrmuzd takes advantage of Ahriman's incapacity to create life without intervention. When Ahriman recovers, he creates Jeh, the primal seductress who afflicts women with their menstrual cycles. In Bundahishn 4.12, Ahriman perceives that Ohrmuzd is superior to himself, and so flees to fashion his many demons with which to conquer the universe in battle. The entire universe is finally divided between the Ohrmuzd and the yazads on one side and Ahriman with his devs on the other. Ahriman slays the primal bull, but the moon rescues the seed of the dying creature, and from it springs all animal creation. But the battle goes on, with mankind caught in the middle, whose duty it remains to withstand the forces of evil through good thoughts, words and deeds.

Other texts see the world created by Ohrmuzd as a trap for Ahriman, who is then distracted by creation and expends his force in a battle he cannot win. (The epistles of Zatspram 3.23; Shkand Gumanig Vichar 4.63–4.79). The Dadistan denig explains that Ohrmuzd, being omniscient, knew of Ahriman's intent, but it would have been against his "justice and goodness to punish Ahriman before he wrought evil [and] this is why the world is created."[2]

Ahriman has no such omniscience, a fact that Ohrmuzd reminds him of (Bundahishn 1.16). In contrast, in Manichaean scripture, Mani ascribes foresight to Ahriman.[10]

Some Zoroastrians believed Ahriman "created dangerous storms, plagues, and monsters during the struggle with Ahura Mazda" and that the two gods were twins.[11]

In present-day Zoroastrianism

In 1862, Martin Haug proposed a new reconstruction of what he believed was Zoroaster's original monotheistic teaching, as expressed in the Gathas – a teaching which he believed had been corrupted by later Zoroastrian dualistic tradition as expressed in post-Gathic scripture and in the texts of tradition.[12] For Angra Mainyu, this interpretation meant a demotion from a spirit coequal with Ahura Mazda to a mere product of Ahura Mazda. Haug's theory was based to a great extent on a new interpretation of Yasna 30.3; he argued that the good "twin" in that passage should not be regarded as more or less identical to Ahura Mazda, as earlier Zoroastrian thought had assumed,[13] but as a separate created entity, Spenta Mainyu. Thus, both Angra Mainyu and Spenta Mainyu were created by Ahura Mazda, and should be regarded as his respective 'creative' and 'destructive' emanations.[13]

Haug's interpretation was gratefully received by the Parsis of Bombay, who at the time were under considerable pressure from Christian missionaries (most notable amongst them John Wilson)[14] who sought converts among the Zoroastrian community and criticized Zoroastrianism for its alleged dualism as contrasted with their own monotheism.[15] Haug's reconstruction had also other attractive aspects that seemed to make the religion more compatible with nineteenth-century Enlightenment, as he attributed to Zoroaster a rejection of rituals and of worship of entities other than the supreme deity.[16]

These new ideas were subsequently disseminated as a Parsi interpretation, which eventually reached the west and so in turn corroborated Haug's theories. Among the Parsis of the cities, who were accustomed to English language literature, Haug's ideas were more often repeated than those of the Gujarati language objections of the priests, with the result that Haug's ideas became well entrenched and are today almost universally accepted as doctrine.[15]

While some modern scholars[ت][ث] have theories similar to Haug's regarding Angra Mainyu's origins,[13][ج] many now think that the traditional "dualist" interpretation was in fact correct all along and that Angra Mainyu was always considered to be completely separate and independent from Ahura Mazda.[13][20][21]

Islam

In Islamic discourse, Ahriman embodies the absolute evil (the Devil) in contrast to Iblis (Satan) who represents an original noble being still under God's power.[22] Although the divs, the creations of Ahriman in Zorastian beliefs, entered Islamic literature, to the point of being identified with the demons of Islamic religion,[23][24] Ahriman is mostly a stylistic device to refute the idea of absolute evil. The divs were yet another creation by God although prior to the devils, angels, jinn, and humans, mentioned in the Quran.[25]

Ayn al-Quzat Hamadani asserts that evil exists relational to humans, but always serves a greater purpose. In accordance with tawhid, God is the ultimate source of good and evil.[26] Rumi denies the existence of Ahriman completely:[27]

This is our main quarrel with the Magians (Zoroastrians). They say there are two Gods: the creator of good and the creator of evil. Show me good without evil – then I will admit there is a God of evil and a God of good. This is impossible, for good cannot exist without evil. Since there is no separation between them, how can there be two creators?

Anthroposophy

Rudolf Steiner, who founded the esoteric spiritual movement Anthroposophy, used the concept of Ahriman to name one of two extreme forces which pull humanity away from the centering influence of God. Steiner associated Ahriman, the lower spirit, with materialism, science, heredity, objectivity, and soul-hardening. He thought that contemporary Christianity was subject to Ahrimanic influence, since it tended towards materialistic interpretations. Steiner predicted that Ahriman, as a supersensible Being, would incarnate into an earthly form, some little time after our present earthly existence, in fact in the third post-Christian millennium.[28]

Opus Sanctorum Angelorum

The Opus Sanctorum Angelorum, a debated group inside the Roman Catholic Church, defines Ahriman as a "demon in the Rank of Fallen Powers". It says his duty is to obscure human brains from the Truth of God.[29]

In popular culture

- Temple of Ahriman is a 2016 song by Swedish black metal band Dark Funeral, about Angra Mainyu and the Towers of Silence.

- Various incarnations of Angra Mainyu appear in Type-Moon's Fate series.

- Various incarnations of Angra Mainu and Ahriman appear in Final Fantasy game series.

- The character Ahzek Ahriman from the Warhammer 40,000 setting is based on Angra Mainyu, and his brother Ohrmuzd is based on Ahura Mazda

- DRAUGA by Michael W. Ford is an occult work exploring the lore, mythology and modern magical practice of Yatuk Dinoih (witchcraft) and daeva-yasna (demon-worship) from ancient Persia from a Luciferian approach.

- Angra Mainyu is the lead "deity" of the Mahrkagir of the Drujan kingdom in Kushiel's Avatar, the third book in the Kushiel series by Jacqueline Carey

انظر أيضاً

Footnotes

- ^ Proper names are altogether rare in the Gathas. In these texts, even Ahura Mazda and Amesha Spenta are not yet proper names.

- ^ The translation of mainyu as "spirit" is the common approximation. The stem of mainyu is "man", "thought", and "spirit" is here meant in the sense of "mind".

- ^ The conclusion that the Fiendish Spirit, too, was an emanation of Ahura Mazdah's is unavoidable. But we need not go so far as to assume that Zarathustra imagined the Devil as having directly issued from God. Rather, since free will, too, is a basic tenet of Zarathushtrianism, we may think of the 'childbirth' implied in the idea of twinship as having consisted in the emanation by God of undifferentiated 'spirit', which only at the emergence of free will split into two "twin" Spirits of opposite allegiance. — Gershevitch (1964)[17]

- ^ The myth of the Twin Spirits is a model he set for the choice every person is called upon to make. It can not be doubted that both are sons of Ahura Mazda, since they are explicitly said to be twins, and we learn from Y[asna]. 47.2–3 that Ahura Mazda is the father of one of them. Before choosing, neither of them was wicked. There is therefore nothing shocking in Angra Mainyu's being a son of Ahura Mazda, and there is no need to resort to the improbable solution that Zoroaster was speaking figuratively. That Ohrmazd and Ahriman's brotherhood was later considered an abominable heresy is a different matter; Ohrmazd had by then replaced the Bounteous Spirit; and there was no trace any more, in the orthodox view, of the primeval choice, perhaps the prophet's most original conception. — Duchesne-Guillemin (1982)[18]

- ^ This Western hypothesis influenced Parsi reformists in the nineteenth century, and still dominates much Parsi theological discussion, as well as being still upheld by some Western scholars. — Boyce (1990)[19]

Citations

- ^

For example:

Cobbe, Frances Power (1865). "The Sacred Books of the Zoroastrians". Studies New and Old of Ethical and Social Subjects. London: Trubner & Company. p. 131. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

That the old Zoroastrian could daily say, 'May Ahura Mazda increase ! Broken be the power of Ahrimanes!' is no small evidence how far on the right way his faith had led him.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Duchesne-Guillemin, Jacques (1982), "Ahriman", Encyclopaedia Iranica, 1, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 670–673

- ^ Hellenschmidt, Clarice; Kellens, Jean (1993), "Daiva", Encyclopaedia Iranica, 6, Costa Mesa: Mazda, pp. 599–602

- ^ Talageri, Shrikant G. (2000). The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis (in الإنجليزية). Aditya Prakashan. p. 179. ISBN 9788177420104.

- ^ Bose, Saikat K. (2015-06-20). Boot, Hooves and Wheels: And the Social Dynamics behind South Asian Warfare (in الإنجليزية). Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9789384464547.

- ^ Zaehner, Richard Charles (1955), Zurvan, a Zoroastrian dilemma, Oxford: Clarendon

- ^ "The Book of Arda Viraf", The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East, 7, New York: Parke, Austin, and Lipscomb, 1917

- ^ de Menasce, Jean-Pierre (1958), Une encyclopédie mazdéenne: le Dēnkart. Quatre conférences données à l'Université de Paris sous les auspices de la fondation Ratanbai Katrak, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France

- ^ Modi, Jivanji Jamshedji Modi (1903), Jamasp Namak ("Book of Jamaspi"), Bombay: K. R. Cama Oriental Institute

- ^ Dhalla, Maneckji Nusservanji (1938), History of Zoroastrianism, New York: OUP p. 392.

- ^ Wilkinson, Philip (1999). Spilling, Michael; Williams, Sophie; Dent, Marion (eds.). Illustrated Dictionary of Religions (First American ed.). New York: DK. p. 70. ISBN 0-7894-4711-8.

- ^ Haug, Martin (1884). West, Edward W. (ed.). Essays on the Sacred Language, Writings and Religion of the Parsis (3rd ed.). London, UK: Trubner – via Google Books.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Cf. Boyce, Mary (1982). A History of Zoroastrianism (Third impression, with corrections). Vol. 1: The Early Period. pp. 192–194.

- ^ Wilson, John (1843). The Parsi Religion: Unfolded, refuted, and contrasted with Christianity. Bombay, IN: American Mission Press. pp. 106 ff.

- ^ أ ب Maneck, Susan Stiles (1997). The Death of Ahriman: Culture, identity and theological change among the Parsis of India. Bombay, IN: K.R. Cama Oriental Institute. pp. 182 ff.

- ^ Boyce, Mary (2001). Zoroastrians: Their religious beliefs and practices. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 9780415239028 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gershevitch, Ilya (January 1964). "Zoroaster's own contribution". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 23 (1): 12–38. doi:10.1086/371754. S2CID 161954467.

- ^ Duchesne-Guillemin, Jacques (1982). "Ahriman". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 670–673.

- ^ Boyce, Mary (1990). Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism. University of Chicago Press. p. 16. ISBN 9780226069302 – via Google Books.

- ^ Clark, Peter (1998). Zoroastrianism: An introduction to an ancient faith. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 7–9. ISBN 9781898723783 – via Google Books.

- ^ Nigosian, Solomon Alexander (1993). The Zoroastrian Faith: Tradition and modern research. McGill – Queen's Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780773511446 – via Google Books.

- ^ Asa Simon Mittman, Peter J. Dendle The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous, Routledge 24.02.2017, ISBN 978-1-351-89431-9

- ^ Davaran, Fereshteh. Continuity in Iranian identity: Resilience of a cultural heritage. Vol. 7. Routledge, 2010.

- ^ Nünlist, Tobias (2015). Dämonenglaube im Islam [Islamic Belief in Demons] (in الألمانية). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4.

- ^ Abedinifard, Mostafa; Azadibougar, Omid; Vafa, Amirhossein, eds. (2021). Persian Literature as World Literature. Literatures as World Literature. USA: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 40–43. ISBN 978-1501354205, ISBN 9781501354205

- ^ Rustom, Mohammed. "Devil’s advocate: ʿAyn al-Quḍāt’s defence of Iblis in context." Studia Islamica 115.1 (2020): 65-100.

- ^ Asghar, Irfan. The Notion of Evil in the Qur'an and Islamic Mystical Thought. Diss. The University of Western Ontario (Canada), 2021.

- ^ Steiner, Rudolph (1985). The Ahrimanic Deception. Spring Valley, New York: Anthroposophic Press. p. 6.

Lecture given by Rudolf Steiner in Zurich October 27th, 1919

- ^ Das Handbuch des Engelwerkes. Innsbruck, 1961. p. 120.

External links

Media related to Ahriman at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ahriman at Wikimedia Commons

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles having different image on Wikidata and Wikipedia

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles containing آڤستان-language text

- Articles containing فارسية-language text

- Articles containing Middle Persian-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2016

- المقالات needing additional references from October 2022

- كل المقالات needing additional references

- Pages using div col with small parameter

- Ancient Iranian gods

- Chaos gods

- Daevas

- Demons in the ancient Near East

- Destroyer gods

- Devils

- Evil gods

- Iranian words and phrases

- Zoroastrianism

- Yazatas

- Iranian deities

- Iranian gods

- Divine twins