آشور (إله)

| Ashur | |

|---|---|

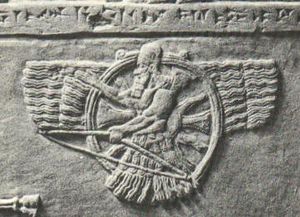

"الرامي لابس الريش" هو تصوير آشوري جديد يرمز لآشور. اليد اليمنى ممدودة مثل شخصية فراڤهار، بينما اليد اليسرى ممسكة بالقوس بدلاً من الحلقة (نقش باررز من القرن 8 أو 9 ق.م.) | |

| أسماء أخرى |

|

| مركز العبادة الرئيسي | Assur, Uruk (6th century BC) |

| معلومات شخصية | |

| الأشقاء | Šerua |

| القرين | Mullissu (Ishtar of Arbela, Ishtar of Assur, Ishtar of Nineveh), Šerua |

| الأنجال | Ninurta, Zababa, Šerua, Ishtar of Arbela |

آشور (بالحروف اللاتينية: Ashur أو Assur، Aššur؛ وتـُكتب آ-شور، وأيضاً آش-شور، ܐܫܘܪ K Sumerian: 𒀭𒊹 AN.ŠAR₂, Assyrian cuneiform: ![]()

![]() Aš-šur,

Aš-šur, ![]()

![]() ملف:Assyrian cuneiform U121F3 MesZL 751 and MesZL 752.svg

ملف:Assyrian cuneiform U121F3 MesZL 751 and MesZL 752.svg![]() da-šur4)[1] هو إله الشمس وإله مدينة آشور. وهو أعظم الآلهة لدى الآشوريين في الأزمنة القديمة حتى اعتنقوا تدريجياً المسيحية بين القرنين الأول والخامس.

da-šur4)[1] هو إله الشمس وإله مدينة آشور. وهو أعظم الآلهة لدى الآشوريين في الأزمنة القديمة حتى اعتنقوا تدريجياً المسيحية بين القرنين الأول والخامس.

Name

The name of the god Ashur is spelled exactly the same as that of the city of Assur. In modern scholarship, some Assyriologists choose to employ different spellings for the god vis-a-vis the city as a means to differentiate between them. In the Old Assyrian Period, both the city and the god were commonly spelled as A-šùr. The god Ashur was spelled as dA-šur, A-šur, dA-šùr or A-šùr, and from the comparative data there seems to be a bigger general reluctance to use the divine determinative in Anatolia in comparison to data from the city of Assur itself.[2] From the Middle Assyrian period onwards, Aššur was generally spelled as Aš-šur, for the god, the city and the state (māt Aššur = Assyria).

Ashur's name was written once as AN.ŠÁR on a bead of Tukulti-Ninurta I. In the inscriptions of Sargon II Ashur was sometimes referred to as Anshar, and under Sennacherib it became a common systemic way to spell his name.[3] After the fall of the Assyrian state, Ashur continued to be revered as Anshar in Neo-Babylonian Uruk. As Assyrian kings were generally reluctant to enforce worship of Ashur in subject areas, it is assumed that Ashur was introduced to Uruk naturally by Assyrians.[4]

History

Third Millennium BCE

Little is known about the city of Assur in the Third Millennium, but the city may have had a religious significance.[5] While the city did contain a temple dedicated to their own localised Ishtar (Ishtar of Assur), there are no known mentions of Ashur as a distinct deity,[6] and it is unknown if the cult of Ashur existed at this time,[7] although the possibility cannot be ruled out because of scarcity of evidence.[6]

Old Assyrian Period

The Old Assyrian Period is contemporary with the Isin-Larsa and Old Babylonian Periods in southern Mesopotamia after the city became independent from Ur. During the Old Assyrian period, the temple to the god was built and maintained by the residences of the city. Ashur started to appear in texts such as treaties and royal inscriptions, and the king traced their legitimacy to the god.[8] In the Old Assyrian period, the kings never assumed the title of king, instead referring to themselves as the governor (iššiak) or city ruler (rubā'um), reserving the title of king instead for Ashur.[9] Pongratz-Leisten notes that similar cases could be found in Pre-Sargonic Lagash, where the kings of Lagash designated themselves as the ENSI (governor) of Lagash, and also in Eshnunna, especially since the early kings of Eshnunna addressed Tishpak with titles traditionally associated with kings such as "king of the four corners."[10] However, in the Old Assyrian Period the king was not yet the chief priest of Ashur.[11]

The earliest expression of the god Ashur being the king of the city with the ruler being his representative was in Silulu's seal, where the opening lines were "Ashur is king, Silulu is the governor (iššiak) of Assur." The inscription ended with the phrase ARAD-ZU, linking the seal with the Ur III administration,[12] but instead of a presentation scene, a triumphant figure is shown trampling on an enemy, bearing resemblance to Naram-Sin's pose on his victory stela and the lost depiction of Shu-Sin trampling on his enemy.[12] Coupled with the ideology of Ashur being the king of the city, the victorious figure could represent Ashur. [12][أ] The Puzur-Assur dynasty reused the presentation scene, which depicts a worshipper (the seal owner) being led by a goddess to a seated god. Considering that the owner of the seal was the Assyrian ruler, it is likely that the seated god is Ashur.[13]

Almost half of Old Assyrian theophoric names feature the god Ashur, with around another 4 percent featuring ālum (city) which referred to the city of Assur. However, it is not clear whether the term Aššur in the names refers to the god or the city.[14] Theophoric names involving Ashur are generally exclusively Assyrian.[15]

Outside of the city of Assur, Assyrian merchant colonies in Anatolia constructed sanctuaries to the god Ashur,[16] which included the objects like his statue and his dagger and knife/spear.[17] Oaths were sworn[18] and verdicts were issued[19] in front of the dagger. The dagger seemed to have also received libations.[20] The weapon of Ashur, more famously known to have been placed in Assyrian provincial centres and client states in the Neo-Assyrian period,[21] were also known in the Old Assyrian period and were seemingly used in ordeals (together with the sword of Ashur and another symbol of Ashur)[22] where the defendant would have to draw the weapon out from its sheath, as the guilty would be unable to draw out the weapon due to divine refusal.[23] Traders would swear by the names of gods such as Ashur, Ishtar, Ishtar-ZA-AT, and Nisaba that they were speaking truth. [18]Traders are often encouraged to go back to the city of Assur to pay homage to Ashur.[11]

In 1808 BCE, Shamshi-Adad captured Assur, dethroned the Assyrian king and incorporated Assur into his kingdom. While he never set Assur as his seat of kingship, he assumed the position of king in the city and left inscriptions calling himself the viceroy of Ashur, in line with the traditional Old Assyrian inscriptions,[24] and reconstructed the temple of Ashur into a bigger complex, and the groundplan remained relatively unaltered until Shalmaneser I who added a backyard.[25] However, he was first the appointee (šakin) of Enlil, and in one of his building inscriptions he designated the Ashur temple as a temple of Enlil instead.[26] Shamshi-Adad's inscription equating the Ashur temple as a temple of Enlil has commonly been interpreted to be the first reference to an equation between Ashur and Enlil.[27][28] Another possibility is that Shamshi-Adad constructed separate cells in the new temple, which housed both Ashur and Enlil.[28] His inscriptions also always applies the divine determinative to the name of the god Ashur, unlike earlier times.[29] However, in a late 17th century letter written by the Assyrian king to the king of Tikunani uses inconsistent sign markings for the term Aššur, once being accompanied by both the divine determinative and the geographical determinative.[30]

The tākultu festival was first attested during the reign of Shamshi-Adad I on a vase dedicated to Dagan. It would seem that the festival was already part of the cult of Ashur.[31]

The inscription of Puzur-Sin presents a hostile attitude towards Shamshi-Adad and his successors, claiming that they were a "foreign plague" and "not of the city of Assur." Puzur-Sin claims that Ashur commanded him to destroy the wall and palace of Shamshi-Adad.[32]

Middle Assyrian Period

Beginning in the Middle Assyrian Period, the Assyrian kings projected a more territorial ideology, with the king acting as the agent of placing the territory under divine rule.[33] The practice where each province had to supply yearly a modest amount of food for the daily meal of Ashur, which ideologically demonstrated how all of Assyria was to jointly care for their god,[34] was first attested during the Middle Assyrian period.[33] the tākultu festival was also mentioned in the inscriptions of Adad-nirari I and his successor Shalmaneser I.[35] However, mentions of the tākultu ritual in Assyria ceased until the Sargonids.[36]

Starting from Ashur-uballit, the Assyrian kings started to designate themselves as king (šarru) and claimed themselves to be a major power.[37] In addition to emulating the other great powers, they also adopted most of Shamshi-Adad I's royal titulature, including being the appointee of Enlil before being the viceroy of Ashur.[38] Despite this, the Old Assyrian notion that the true king of Assur was the god Ashur persisted, as seen in the Middle Assyrian coronation ritual that was carried out inside the temple of Ashur. The king is led inside the temple where a priest would strike the king's cheek and proclaim "Ashur is king! Ashur is king!"[39] Ashur-uballit also introduced the title SANGA/šangû into the royal repertoire, which may have been the product of a Hittite influence.[40] The practice for the king’s reign to be referred with "during my priesthood" (ina šangûtīya) was also introduced during the Middle Assyrian period.[41]

The Assyrian king was also given the mission to extend the land of Assyria with his "just sceptre" as mentioned in the coronation hymn.[42] Royal actions undertaken, such as military campaigns and successes, were attributed to the support of the god Ashur, along with the other major gods in the Assyrian pantheon.[43][44] Similar to the city of Assur, the land of Aššur (Assyria) shared the same name as the god Ashur, which essentially meant that the country belonged to the god.[45] Starting from the Middle Assyrian period (and extending into the Neo Assyrian period), the mission of the Assyrian king was to extend the borders of Assyria and establish order and peace against a chaotic periphery.[46]

Ashur started to be referred to more often as an Assyrian equivalent of Enlil, with titles such as "lord of the lands" (bēl mātāte), "king of the gods" (šar ilāni) and "the Assyrian Enlil" (Enlil aššurê).[45] Adad-nirari and Shalmaneser began to call the temple of Ashur names of Enli's temple in Nippur, and Shalmaneser even claimed to have put the gods of Ekur into the temple.[47] The construction of Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta was attributed to the command of Ashur-Enlil.[48] However, Enlil and Ashur were still treated as separate gods in the Tukulti-Ninurta Epic, and some traits of Enlil were not carried over to Ashur, especially in regards to how Ea and Enlil raised the young Tukulti-Ninurta (in line with southern traditions), a role which was not given to the god Ashur.[49]

Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta, constructed by the eponymous king himself (the name of the city means "quay of Tukulti-Ninurta") was explicitly stated to be a cult centre for Ashur.[50] The building of a new capital and cult centre is traditionally viewed as an attempt to separate the royal monarchy from the established elites and pressure groups,[51] however it is clear that the city of Assur was still respected as building works were still done in Assur, the main palace at Assur was still being constantly maintained,[50] and the perimeter of the ziggurat in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta was half of the one in Assur.[52] The main bureaucracy in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta was connected with the city of Assur as well.[52] Assur was still referred with epithets such as "my city" (ālīya) and "desired object of the deities" (ba-it ilāni), although they could refer to Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta as well.[53]

Neo Assyrian Period

The Middle Assyrian practice of provincial provisions to the temple of the god Ashur remained during Sargonid Assyria.[54]

Ashur continued to play a pivotal role in Assyrian imperial ideology in the Neo-Assyrian period. Enemies were often portrayed to have violated the oath to Ashur and the gods of Assyria, and that he had no respect for the gods.[55] In celebrative texts, the oaths imposed on the defeated are sworn in the name of Ashur, extending to the other gods of Assyria in the late Neo-Assyrian period.[56][ب] Royal actions were said to be undertaken under the command of Ashur with the king acting as his proxy,[58] with the central mission being to expand the borders of Assyria. The territories controlled by Ashur was aligned with the cosmos,[59] and expanding the lands of Assyria meant expanding the cosmos to include the previously disorderly periphery.[60] The Assyrian king was the chief priest of Ashur, and while not considered a god (in life or in death) the king is in the image of a god.[61] In Ashurbanipal's Coronation Hymn, the idea that Ashur was the true king reappeared, reflecting on an ideological discourse tracing all the way back to the Old Assyrian period.[61]

Sennacherib, in the aftermath of his infamous destruction of Babylon in 689 BCE, reformed aspects of Ashur's cult. He built a new akītu house in Assur, and Ashur instead of Marduk was the centre of the festival.[62] An Assyrian revision of the Enuma Elish replaced Marduk with Ashur as the main character of the epic.[62][63] A change observed during the reign of Sargon II,[62] which became more systemic under Sennacherib,[3] was the equation of Ashur with Anshar, by writing the name of the god Ashur as AN.ŠÁR.[ت]

Sennacherib's son and successor, Esarhaddon, chose to pursue a more conciliatory route with Babylonia. Esarhaddon addressed both the people of Assyria and Babylonia with identical terms in an attempt to group them under one audience,[64] and the gods Marduk, Nabu and Tashmetum were invoked naturally along with the traditionally Assyrian gods.[65] The inscription also claims that Bēl, Bēltiya, Bēlet Babili, Ea, and Mandanu were born in Esharra, the house of their father, which here refers to the temple of Ashur, and refers to Ashur as the "father of the gods" and Marduk as the "first heir."[66] The political and theological implications of such was that the Babylonian gods were to be adopted into the Assyrian pantheon, and the relationship of Marduk vis-a-vis Ashur (son and father) would reflect the relationship Babylonia has with Assyria, with Assyria in the politically dominant position and Babylonia holding a special position within the empire.[67][ث]

There have been suggestions that the worship of Ashur was forcibly imposed onto subject vassals. However, this notion has been challenged by other scholars, most notably Cogan, who concluded that the idea that the cult of Ashur and other Assyrian gods were imposed onto defeated subjects should be rejected, and residents in the annexed provinces were required to provide for the cult of Ashur as they were counted as Assyrian citizens[69] and it was the duty of Assyrian citizens to do so.[70]

Assyrian imperial ideology affirms Ashur's superiority, and the vanquished are obliged to acknowledge the superiority of the Assyrian god and king, however they are not obliged to renounce their own religious traditions.[71] Assyrian kings sometimes claimed to have erected statues of the king and the Assyrian gods in the provincial palace in newly conquered territories, but this does not indicate the imposition of a cult onto the populace.[72] Liverani summarises that there was no intention to convert others to the worship of Ashur, only that Ashur should be recognized as the most powerful god and fit to rule over others.[73]

Olmstead believed that the imposition of the weapon of Ashur onto provinces and client states implies a forced worship of Ashur, but Holloway disagreed, mentioning the usage of the weapon of Ashur in Old Assyrian times, believes the main purpose of the weapon is to serve as a witness to the adê-oaths.[74] Liverani also believes the weapon to have had a celebratory function rather than a cultic one.[75]

A recent discovery in the provincial capital city of Kullania uncovered a copy of Esarhaddon's succession treaty inside a temple, next to a pedestal. The tablet itself is inscribed in a way that the obverse and reverse are both readable when stood on its short side, in contrast to the other Assyrian treaty tablets, where you had to flip the tablet horizontally to read the reverse. This along with the location of the discovery suggests that the tablet was considered an object of worship.[76] It's uncertain whether this was an innovation during Esarhaddon's reign or if it was already practised prior.[77]

Within Babylonia, outside of the rare mentions of offerings to Ashur after putting down a rebellion, there are no holy structures such as shrines and temples dedicated to Ashur in Babylonia,[78] nor were there mentions of Assyrian cults established in the Babylonian temples.[79] von Soden had suggested before that the Babylonians purposefully rejected Ashur, but Frame disagrees, and argues that since Ashur was the national god of Assyria with barely any character of his own, the average Babylonians probably just didn’t care much about him.[80]

The universal imperial ideology surrounding Ashur is suggested to have influenced Judah's own religious discourse surrounding Yahweh.[81] Especially within the First Isaiah, ideological discourse surrounding Assyria and the god Ashur were said to be adapted to Yahweh in an effort to counter Assyria,[82][83] and the trend of depicting kings of powerful foreign empires as servants of Yahweh started with the Assyrian kings.[84] The more far-fetched theories about Assyrian influence on Christianity put forward mainly by Parpola are usually rejected.[85]

The city of Assur was sacked by the Median forces in 614 BCE, and the Temple of Ashur was destroyed in the process.[77]

Post Imperial Assyria

After the fall of the Assyrian state, a small independent sanctuary dedicated to Anshar was attested in Neo-Babylonian Uruk, which can be understood to be a cult dedicated to the Assyrian god Ashur.[86] The grammatically Assyrian names, as well as the mention of "the city" (referring to Assur) points to a community of Assyrians during the time in Uruk.[87] The cult was likely introduced naturally without coercion as Assyrian rulers didn't impose the cult of Ashur on conquered territories, and a strong pro-Assyrian faction was attested in Uruk during the rebellion of Nabopolassar.[4] Beaulieu also suggests another reason to be that Anshar (Ashur) may have been equated with Anu.[4] Although references to the sanctuary all come from the 6th century BCE, It is unknown when the sanctuary to Ashur in Uruk was established. Beaulieu had suggested that it may have been introduced in the 7th century BCE by the strong pro-Assyrian party, as evidenced by the name of a qēpu known as Aššur-bēl-uṣur.[88] Radner disagrees, as qēpus were directly appointed by the Assyrian kings and generally seen as outsiders, providing no evidence for a sanctuary to Ashur during that time, and argues that the sanctuary was likely established by refugees from Assyria.[89]

After Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon, he claimed to have returned the gods from Assur, Susa, Akkad, Eshnunna, Zamban, Me-Turan, Der and the Zagros Mountains back to their original places, along with their people as per the Cyrus Cylinder.[90] Radner argues that the new temple on top of the old destroyed Ashur temple, called "Temple A" by the excavator Walter Andrae, may have been a new temple to Ashur built after the return of the statue of Ashur,[90] and the usage of old cuneiform texts to build the temple can be seen as an appreciation for the past.[91] Shaudig, on the other hand, believes that Temple A was built during the Neo-Babylonian times,[92] and disagrees with Radner that the pre-Parthian Temple A was built to honour the history of Assyria,[93] and the usage of the ancient texts as flooring implies a more mocking stance.[94]

During the Seleucid period Ashur (rendered Assor) also appears as the theophoric component in Aramaic names.[95] One of the attested names was Ahhiy-Assor (lit. my brother is Ashur) may indicate that Ashur was now seen as more approachable.[96] In the Parthian period, a group of iwans were constructed over the ruins of the old Ashur temple. Worshippers scratched the names of the deities on the third iwan, and among the deities the gods Ashur and Šerua appeared the most often.[97] A Parthian era building was also erected on the ruins of Sennacherib's akītu house following a similar ground plan, indicating the survival of the cult.[98]

Characteristics and Iconography

Ashur is a god intrinsically associated with his city. The inscription of Zarriqum, the Ur III governor of Assur, writes Aššur with both the divine determinative and geographical determinative. However, this spelling is not attested in subsequent royal inscriptions,[99] reappearing once in a treaty between the king of Assur and the king of Tikunani.[30] Old Assyrian documents from Anatolia are sometimes unclear with the usage of determinatives, lacking a distinction between the city and the god.[100] He also lacks characteristics, stock epithets or a divine persona in general,[101] and no early mythology surrounding Ashur is known.[102] He has no attributes and traits, solely representing the city (and later the state) and its power.[103]

Lambert had suggested that the god Ashur was the deified hill upon which the city of Assur was built.[5] It is also likely that the cliff over the Tigris river near the city of Assur was the original cult place of Ashur.[104]

A possible representation of Ashur in Old Assyrian seals is the bull altar motif, which appears commonly in seals from Kanesh[105] and also in Assur,[106] with the motif appearing on seals belonging to high officials in Assur.[107] The bull altar can also be the subject of worship on the seal and occasionally replaces the crescent in the presentation scenes.[108] A similar motif is found in the seal of the city hall, which depicts a goddess standing in front of a mountain with a bull head. Since the seal is said to also belong to the divine Ashur, it is likely that the bull represents Ashur.[109][110]

A relief found in a well in the inner courtyard of the temple of Ashur in the city of Assur portrays a mountain god flanked by two water-goddesses. Cones growing from the side of the figure, which were being nibbled by two goats. The figure's nose and mouth were badly damaged, suggesting that it was deliberately vandalised and thrown into the well along with other debris following the conquest of the city of Assur in 614 BCE.[111] There is good evidence to suggest that the figure in question is the god Ashur,[112] especially once you consider that the image was specifically mutilated and thrown down a well.[113]

The wild goat is suggested to be the sacred animal of Ashur.[114] The goat appears several times as a symbol in Assyrian cylinder seals,[115] and also in Neo-Assyrian art such as the royal pavilions of Ashurnasirpal and Shalmaneser III.[112] The cone could also be considered to be a symbol of Ashur.[116] The Neo-Assyrian sun disc is generally viewed to represent Ashur. However, some scholars argue that the disc represents something else, such as another god,[117] or that it represents Shamash instead.[118] Similarly, the chariot standard is also argued to represent another god.[117]

Ashur was never consulted oracularly in the Neo-Assyrian period, and never appeared in Akkadian exorcism literature. [119] However, in the Annals of Tiglath-pileser III, the king claimed that Ashur gave him oracular consent by confirmation through an omen before each campaign.[120]

Family and Relationships

In contrast to many other gods, Ashur lacks original familial connections.[121] Mullissu, who is to be identified with Ninlil, reflects instead the identification of Ashur with Enlil,[ج] and it is the same for Ninurta and Zababa, sons of Enlil who were occasionally identified as Ashur's sons.[121] The only native relative of Ashur is the goddess Šerua, but Assyrian sources are divisive on whether she was Ashur's wife, daughter,[121] or sister.[123] Šerua was referred to as Ashur's daughter by Tukulti-Ninurta I, but later Tiglath-pileser III referred to her as Ashur's wife,[124] and a Neo-Assyrian text claims that Šerua should not be referred to as Ashur's daughter but as his wife instead.[125]

Tallqvist, when studying Old Assyrian inscriptions, noted that different manifestations of Ishtar are occasionally mentioned alongside Ashur and concluded that Ishtar was seen as Ashur's wife in the Old Assyrian Period. However, Meinhold finds this unlikely as Ishtar only came to be seen as Ashur's consort or wife during the Neo-Assyrian Period.[126][ح] Another Neo-Assyrian text claims Ishtar of Arbela to be Ashur's daughter.[129]

In a bilingual prayer of Tukulti-Ninurta I to the god Ashur, Nusku is listed as Ashur's vizier.[27]

In the Assyrian recension of the Enuma Elish, Ashur's parents were listed as Lahmu and Lahamu. However, subsequent inscriptions from Sennacherib claimed that Ashur effectively created himself, which is reaffirmed in the so-called "Marduk Ordeal" that claimed Ashur came into being from nothingness.[130]

Texts and Literature

Marduk Ordeal

Written in the Assyrian dialect,[131] versions of the so called Marduk Ordeal Text are known from Assur, Nimrud and Nineveh.[62] Using sceneries and language familiar to the procession of the Akitu Festival, here Marduk is instead being held responsible for crimes committed against Ashur and was subject to a river ordeal and imprisonment.[62] Nabu arrives in Babylon looking for his father Marduk, and Tashmetum prayed to Sin and Shamash.[132] Meanwhile, Marduk was being held captive, the color red on his clothes was reinterpreted to be his blood, and the case was brought forward to the god Ashur. The city of Babylon also seemingly rebelled against Marduk, and Nabu learned that Marduk was taken to the river ordeal. Marduk claims that everything was done for the good of the god Ashur and prays to the gods to let him live, while Sarpanit was the one who prays to let Marduk live in the Ninevite version.[133] After various alternate cultic commentaries, the Assyrian version of the Enuma Elish was recited, proclaiming Ashur's superiority.[134]

Assyrian Enuma Elish

The content of the Assyrian recension of the Enuma Elish remains largely the same, except that Marduk was replaced by Ashur, written as Anshar. This creates a dilemma where two Anshars are attested in the myth, one being the old king of the gods, and one being the great-grandson, the new king of the gods. Lambert attributed this inconsistency to poor narrative skills, although Frahm believes that this was intentional, to give Ashur both genealogical superiority and political superiority.[135]

ملاحظات

- ^ Similarly, the god Tishpak was also sometimes addressed with Ur III royal titles.[12]

- ^ In the actual treaties however, gods from both parties were invoked, indicating that gods from both parties needed to be present for the treaty to work[57]

- ^ Although the writing AN.ŠÁR for Ashur was first attested in an inscription of Tukulti-Ninurta I.

- ^ In another copy, the relationship of Marduk as Ashur's son was not stated. It could be that this other copy was intended for the Babylonian audience, who may not have accepted the drastic change in Marduk's genealogy.[68]

- ^ However, Mullissu gradually became a title for the wife of Ashur[122]

- ^ Three main Ishtars shared the title of Mullissu in late Assyrian texts, being Ishtar of Assur, Ishtar of Arbela and Ishtar of Nineveh.[127] Assyrian texts do not always make it clear which Ishtar they are referring to.[128]

الهامش

- Aster, Shawn Z. (4 December 2017). Reflections of Empire in Isaiah 1-39: Responses to Assyrian Ideology. SBL Press. ISBN 978-1628372014.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1997). "The Cult of AN.ŠÁR/Aššur in Babylonia After the Fall of the Assyrian Empire". State Archives of Assyria Bulletin. 11: 55–73.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (11 July 2003). "The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period". The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period (in الإنجليزية). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-49680-4.

- Cogan, Mordechai (1974). Imperialism and religion: Assyria, Judah, and Israel in the eighth and seventh centuries B.C.E. [Missoula, Mont.] : Society of Biblical Literature : distributed by Scholars Press. ISBN 978-0-88414-041-2.

- Eppihimer, Melissa (2013). "Representing Ashur: The Old Assyrian Rulers' Seals and Their Ur III Prototype". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 72 (1): 35–49. doi:10.1086/669098. ISSN 0022-2968.

- Frahm, Eckart (2010). "Counter-texts, Commentaries, and Adaptations: Politically Motivated Responses to the Babylonian Epic of Creation in Mesopotamia, the Biblical World, and Elsewhere". Orient. 45: 3–33.

- Frahm, Eckart (18 May 2017). "Chapter 29: Assyria in the Hebrew Bible". In Frahm, Eckart (ed.). A Companion to Assyria (in الإنجليزية). Wiley Blackwell. pp. 556–569. doi:10.1002/9781118325216.ch29.

- Frame, Grant (1995). "The god Aššur in Babylonia". In Parpola, Simo; Whiting, Robert (eds.). Assyria 1995: Proceedings of the 10th Anniversary Symposium of the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, Helsinki, September 7 - 11, 1995. Eisenbrauns. pp. 336–358.

- Frymer-Kensky, Tikva (1983). "The Tribulations of Marduk the So-Called "Marduk Ordeal Text"". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 103 (1): 131–141. doi:10.2307/601866. ISSN 0003-0279.

- Gilibert, Alessandra (2008). "On Kār Tukultī-Ninurta: chronology and politics of a Middle Assyrian ville neuve". Fundstellen: Gesammelte Schriftenzur Archäologie und Geschichte Altvorderasiensad honorem Hartmut Kühne.

- Grayson, A. Kirk (1985). "Rivalry over Rulership at Assur The Puzur-Sin Inscription" (PDF). Annual Review of the RIM Project. 3: 9–14.

- Haider, Peter (2008). "Tradition And Change In The Beliefs At Assur, Nineveh And Nisibis Between 300 BC And AD 300". In Kaizer, Ted (ed.). The variety of local religious life in the Near East: in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Brill. pp. 193–207.

- Hirsch, Hans (1961). Untersuchungen sur altassyrischen religion. Im Selbstverlage des Herausgebers.

- Holloway, Steven Winford (2002). Aššur is King! Aššur is King!: Religion in the Exercise of Power in the Neo-Assyrian Empire (in الإنجليزية). BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-12328-1.

- Karlsson, Mattias (23 May 2015). "The Theme of Leaving Assur in the Royal Inscriptions of Tukulti-Ninurta I and Ashurnasirpal II".

- Krebernik, M (2011). "Šerūʾa". BAdW · Reallexikon der Assyriologie. 12: 399–400.

- Lambert, W. G. (1983). "The God Aššur". Iraq. 45 (1): 82–86. doi:10.2307/4200181. ISSN 0021-0889.

- Lassen, Agnete Wisti (2017). "The 'Bull-Altar' in Old Assyrian Glyptic: a representation of the god Assur". KIM. 2: 177–194.

- Levine, Baruch A. (2005). "Assyrian Ideology and Israelite Monotheism". Iraq. 67 (1): 411–427. ISSN 0021-0889.

- Liverani, Mario (2017). Assyria: The Imperial Mission (in الإنجليزية). Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-1-57506-754-4.

- Livingstone, Alasdair (1989). Court poetry and literary miscellanea. State Archives of Assyria. Helsinki: Univ. Pr. ISBN 951-570-043-4.

- Livingstone, A. (2009). "Remembrance at Assur: The Case of the dated Aramaic memorials". Studia Orientalia Electronica. 106: 151–157.

- Machinist, Peter (1976). "Literature as Politics: The Tukulti-Ninurta Epic and the Bible". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 38 (4): 455–482. ISSN 0008-7912.

- Maul, Stefan M. (2017). "Chapter 18: Assyrian Religion". In Frahm, Eckart (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Wiley Blackwell. pp. 336–358. doi:10.1002/9781118325216.ch18.

- Meinhold, Wiebke (1 January 2014). "Die Familie des Gottes Aššur". L. Marti (ed.), La famille dans le Proche-Orient ancien: réalités, symbolismes, et images: 141–149.

- Nielsen, John Preben (2018). The reign of Nebuchadnezzar I in history and historical memory. New-York (N.Y.): Routledge. ISBN 978-1138120402.

- Pongratz-Leisten, Beate (2011). "Assyrian Royal Discourse Between Local and Imperial Traditions at the Hābūr". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 105: 109–128. ISSN 0373-6032.

- Pongratz-Leisten, Beate (25 September 2015). "Religion and Ideology in Assyria". Religion and Ideology in Assyria (in الإنجليزية). De Gruyter. ISBN 978-1-61451-426-8.

- Porter, Barbara N. (1993). Images, Power, and Politics: Figurative Aspects of Esarhaddon's Babylonian Policy (in الإنجليزية). American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-208-5.

- Porter, Barbara Nevling (2004). "Ishtar of Nineveh and Her Collaborator, Ishtar of Arbela, in the Reign of Assurbanipal". Iraq. 66: 41–44. doi:10.2307/4200556. ISSN 0021-0889.

- Radner, Karen (2017). "Assur's 'Second Temple Period': the restoration of the cult of Assur, c. 538 BC". In Levin, Christoph; Müller, Reinhard (eds.). Herrschaftslegitimation in vorderorientalischen Reichen der Eisenzeit (in الإنجليزية). Mohr Siebeck. pp. 77–96. doi:10.5282/UBM/EPUB.36940 – via Universitätsbibliothek der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München.

- Reade, Julian; Freydank, H. (2000). "Das Kultrelief aus Assur: Glas, Ziegen, Zapfen und Wasser". Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft.

- Schaudig, Hanspeter (2018). "Zum Tempel "A" in Assur: Zeugnis eines Urbizids". In Kleber, Kristin; Neumann, Georg; Paulus, Susanne (eds.). Grenzüberschreitungen: Studien zur kulturgeschichte des Alten Orientes. Zaphon. pp. 621–635.

- Stepniowski, Franciszek M. (January 2003). "The temples in Assur: an overview of the sacral architecture of the Holy City". ISIMU. 6. doi:10.15366/isimu2003.6.013. hdl:10486/3480. ISSN 2659-9090.

- Ungen, Eckhard (1965). "Die Symbole des Gottes Assur". BELLETEN. 29: 423–484.

- Valk, Jonathan (May 2018). Assyrian Collective Identity in the Second Millennium BCE: A Social Categories Approach -dissertation (PDF). New York University.

- Veenhof, Klaas R.; Eidem, Jesper (2008). Mesopotamia: The Old Assyrian Period (PDF).

- Veenhof, Klaas R. (2017). "Chapter 3: The Old Assyrian Period (20th–18th Century bce)". In Frahm, Eckart (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Wiley Blackwell. pp. 336–358. doi:10.1002/9781118325216.ch3.

- Zaia, Shana (1 December 2015). "State-Sponsored Sacrilege: "Godnapping" and Omission in Neo-Assyrian Inscriptions". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History (in الإنجليزية). 2 (1): 19–54. doi:10.1515/janeh-2015-0006. ISSN 2328-9562.

انظر أيضاً

- Ashurism

- العلم الآشوري، يضم صورة لآشور

- فراڤهار Faravahar

| الآلهة الإسطورية لسوريا القديمة | |

|---|---|

| بعل - عناة - عشتار - حدد - أداد - داجون - آشور | |

- ^ "Sumerian dictionary entry Aššur [1] (DN)". oracc.iaas.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on 2020-07-25. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- ^ Hirsch 1961, p. 6.

- ^ أ ب Beaulieu 1997, p. 64.

- ^ أ ب ت Beaulieu 2003, p. 332.

- ^ أ ب Lambert 1983, p. 85.

- ^ أ ب Valk 2018, p. 107.

- ^ Maul 2017, p. 338.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 127.

- ^ Pongratz-Leisten 2015, p. 103.

- ^ Pongratz-Leisten 2015, p. 108.

- ^ أ ب Veenhof & Eidem 2008, p. 104.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Eppihimer 2013, p. 42.

- ^ Eppihimer 2013, p. 43.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 128.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 154-155.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 137.

- ^ Veenhof & Eidem 2008, p. 56.

- ^ أ ب Veenhof & Eidem 2008, p. 103.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 139.

- ^ Veenhof & Eidem 2008, p. 155.

- ^ Cogan 1974, p. 53.

- ^ Holloway 2002, p. 167-168.

- ^ Cogan 1974, p. 54.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 170-171.

- ^ Stepniowski 2003, p. 235.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 172.

- ^ أ ب Meinhold 2014, p. 142.

- ^ أ ب Valk 2018, p. 173.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 173-174.

- ^ أ ب Valk 2018, p. 129.

- ^ Pongratz-Leisten 2015, p. 393.

- ^ Grayson 1985, p. 12.

- ^ أ ب Pongratz-Leisten 2011, p. 110.

- ^ Maul 2017, p. 344.

- ^ Pongratz-Leisten 2015, p. 393-394.

- ^ Pongratz-Leisten 2015, p. 394.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 200.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 202.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 203-204.

- ^ Pongratz-Leisten 2015, p. 203.

- ^ Pongratz-Leisten 2015, p. 138.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 204.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 206.

- ^ Pongratz-Leisten 2011, p. 112.

- ^ أ ب Valk 2018, p. 208.

- ^ Liverani 2017, p. 13.

- ^ Machinist 1976, p. 469-470.

- ^ Machinist 1976, p. 467.

- ^ Machinist 1976, p. 474.

- ^ أ ب Gilibert 2008, p. 181.

- ^ Gilibert 2008, p. 180.

- ^ أ ب Gilibert 2008, p. 183.

- ^ Karlsson 2015, p. 5.

- ^ Holloway 2002, p. 68.

- ^ Holloway 2002, p. 73-74.

- ^ Liverani 2017, p. 222.

- ^ Zaia 2015, p. 27.

- ^ Liverani 2017, p. 12.

- ^ Pongratz-Leisten 2015, p. 145.

- ^ Liverani 2017, p. 14.

- ^ أ ب Liverani 2017, p. 11.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Nielsen 2018, p. 98.

- ^ Frahm 2010, p. 8.

- ^ Porter 1993, p. 120.

- ^ Porter 1993, p. 122.

- ^ Porter 1993, p. 124.

- ^ Porter 1993, p. 124-125.

- ^ Porter 1993, p. 125.

- ^ Cogan 1974, p. 60.

- ^ Cogan 1974, p. 51.

- ^ Liverani 2017, p. 220.

- ^ Liverani 2017, p. 221.

- ^ Liverani 2017, p. 229.

- ^ Holloway 2002, p. 67.

- ^ Liverani 2017, p. 221-222.

- ^ Radner 2017, p. 80-81.

- ^ أ ب Radner 2017, p. 81.

- ^ Holloway 2002, p. 66-67.

- ^ Holloway 2002, p. 330.

- ^ Frame 1995, p. 63.

- ^ Frahm 2017, p. 561.

- ^ Aster 2017, p. 19.

- ^ Aster 2017, p. 39.

- ^ Levine 2005, p. 423.

- ^ Frahm 2017, p. 566.

- ^ Beaulieu 1997, p. 61.

- ^ Beaulieu 1997, p. 60-61.

- ^ Beaulieu 1997, p. 61-62.

- ^ Radner 2017, p. 84.

- ^ أ ب Radner 2017, p. 85.

- ^ Radner 2017, p. 89.

- ^ Schaudig 2018, p. 621-622.

- ^ Schaudig 2018, p. 628.

- ^ Schaudig 2018, p. 629.

- ^ Livingstone 2009, p. 152.

- ^ Livingstone 2009, p. 154.

- ^ Haider 2008, p. 197.

- ^ Livingstone 2009, p. 156.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 105.

- ^ Lambert 1983, p. 83.

- ^ Lambert 1983, p. 82-83.

- ^ Valk 2018, p. 106.

- ^ Maul 2017, p. 339.

- ^ Maul 2017, p. 340.

- ^ Lassen 2017, p. 182.

- ^ Lassen 2017, p. 183.

- ^ Lassen 2017, p. 185.

- ^ Lassen 2017, p. 181.

- ^ Lassen 2017, p. 187.

- ^ Veenhof 2017, p. 73.

- ^ Reade & Freydank 2000, p. 106.

- ^ أ ب Reade & Freydank 2000, p. 108.

- ^ Reade & Freydank 2000, p. 111.

- ^ Ungen 1965, p. 437.

- ^ Ungen 1965, p. 439-441.

- ^ Reade & Freydank 2000, p. 109.

- ^ أ ب Holloway 2002, p. 66.

- ^ Ungen 1965, p. 463.

- ^ Holloway 2002, p. 65.

- ^ Liverani 2017, p. 16.

- ^ أ ب ت Lambert 1983, p. 82.

- ^ Meinhold 2014, p. 144.

- ^ Krebernik 2011, p. 400.

- ^ Meinhold 2014, p. 145.

- ^ Meinhold 2014, p. 146.

- ^ Meinhold 2014, p. 141.

- ^ Porter 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Porter 2004, p. 43.

- ^ Meinhold 2014, p. 147.

- ^ Meinhold 2014, p. 143.

- ^ Frymer-Kensky 1983, p. 131.

- ^ Frymer-Kensky 1983, p. 134.

- ^ Livingstone 1989, p. 88.

- ^ Livingstone 1989, p. 85.

- ^ Frahm 2010, p. 9.