المعرض العالمي في ڤيينا، 1873

| 1873 ڤيينا | |

|---|---|

The Rotunde, centre of the exhibition | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Universal exposition |

| Category | Historical |

| الاسم | Weltausstellung |

| الشعار | Kultur und Erziehung (إنگليزية: Culture and Education) |

| المبنى | Rotunde |

| المساحة | 233 Ha |

| الزوار | 7,255,000 |

| Location | |

| البلد | النمسا-المجر |

| المدينة | ڤيينا |

| المكان | پراتر |

| الإحداثيات | 48°12′58″N 16°23′44″E / 48.21611°N 16.39556°E |

| خط زمني | |

| افتتح | 1 مايو 1873 |

| الإغلاق | 31 أكتوبر 1873 |

| Universal expositions | |

| السابق | Exposition Universelle (1867) in پاريس |

| اللاحق | المعرض القاري in فيلادلفيا |

المعرض العالمي في ڤيينا، 1873 (ألمانية: Weltausstellung 1873 Wien؛ إنگليزية: World Exposition 1873 Vienna) كان معرضاً عالمياً كبيراً انعقد في عام 1873 في عاصمة النمسا-المجر، ڤيينا. وكان شعاره Kultur und Erziehung (الثقافة والتعليم}}).

There were almost 26,000 exhibitors[1] housed in different buildings that were erected for this exposition, including the Rotunde (إنگليزية: Rotunda), a large circular building in the great park of Prater designed by the Scottish engineer John Scott Russell. The Rotunde was destroyed by fire on September 17, 1937.

The Russian pavilion had a naval section designed by Viktor Hartmann. Exhibits included models of the Port of Rijeka[2] and the Illés Relief model of Jerusalem.[3]

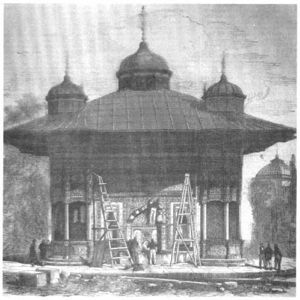

الجناح العثماني

عثمان حمدي بـِيْ، عالم الآثار والرسام، اختارته الحكومة العثمانية كمفوض معارض الدولة العثمانية في فيينا. He organized the Ottoman pavilion with Victor Marie de Launay, a French-born Ottoman official and archivist, who had written the catalogue for the Ottoman Empire's exhibition at the 1867 Paris World's Fair.[4] The Ottoman pavilion, located near the Egyptian pavilion (which had its own pavilion despite being a territory of the Ottoman Empire),[5] in the park outside the Rotunde, included small replicas of notable Ottoman buildings and models of vernacular architecture: a replica of the نافورة السلطان أحمد في Topkapı Palace, a model Istanbul residence, a representative حمام تركي, a cafe, and a bazaar.[6] The 1873 Ottoman pavilion was more prominent than its pavilion in 1867. The Vienna exhibition set off Western nations' pavilions against Eastern pavilions, with the host, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, setting itself at the juncture between East and West.[5] A report by the Ottoman commission for the exhibition expressed a goal of inspiring with their display "a serious interest [in the Ottoman Empire] on the part of the industrialists, traders, artists, and scholars of other nations...."[5]

The Ottoman pavilion included a gallery of mannequins wearing the traditional costumes of many of the varied ethnic groups of the Ottoman Empire. To supplement the cases of costumes, Osman Hamdi and de Launay created a photographic book of Ottoman costumes, the Elbise-i 'Osmaniyye (Les costumes populaires de la Turquie), with photographs by Pascal Sébah. The photographic plates of the Elbise depicted traditional Ottoman costumes, commissioned from artisans working in the administrative divisions (vilayets) of the Empire, worn by men, women, and children who resembled the various ethnic and religious types of the empire, though the models were all found in Istanbul. The photographs are accompanied by texts describing the costumes in detail and commenting on the rituals and habits of the regions and ethnic groups in question.[5]

معرض صور

المدخل الرئيسي إلى المعرض وتظهر خلفه Rotunde.

مجسم إيلش Illés Relief لمدينة القدس.

زي شعبي سويدي معروض في المعرض

الوقع على ڤيينا

The exhibition led to an intensive building activity in the years before. The new train station to Germany Nordwestbahnhof was completed just in time, for example.

الهامش

- ^ Lowe, Charles. Four national exhibitions in London and their organiser. With portraits and illustrations (1892). London, T. F. Unwin. p. 28. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- ^ "PATCHing the city 09". City of Rijeka. 2009. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 19, 2012. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tower of David Museum of the History of Jerusalem | Model of Jerusalem in the 19th Century". Towerofdavid.org.il. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Trencsényi, Balász; Kopečk, Michal (2007). "Osman Hamdi Bey and Victor Marie de Launay: The Popular Costumes of Turkey in 1873". Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770–1945). National Romanticism: Formation of National Movements. Vol. II. Budapest; New York: Central European University Press. pp. 174–180.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Ersoy, Ahmet (2003). "A Sartorial Tribute to Late Tanzimat Ottomanism: The Elbise-i 'Osmaniyye Album". Muqarnas. 20: 187–207 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Çelik, Zeynep (1992). "Islamic Quarters in Western Cities: Universal Exposition of 1873, Vienna". Displaying the Orient: Architecture of Islam at Nineteenth-Century World's Fairs. Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford: University of California Press. ISBN 0520074947.

وصلات خارجية

- Official website of the BIE

Media related to Expo 1873 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Expo 1873 at Wikimedia Commons- The Rotunda of the 1873 Vienna International Exhibition

- Images from the exhibition

| هذا Austrian history article هو بذرة. بإمكانك مساعدة المعرفة بأن تنمـِّـيـه. |

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).